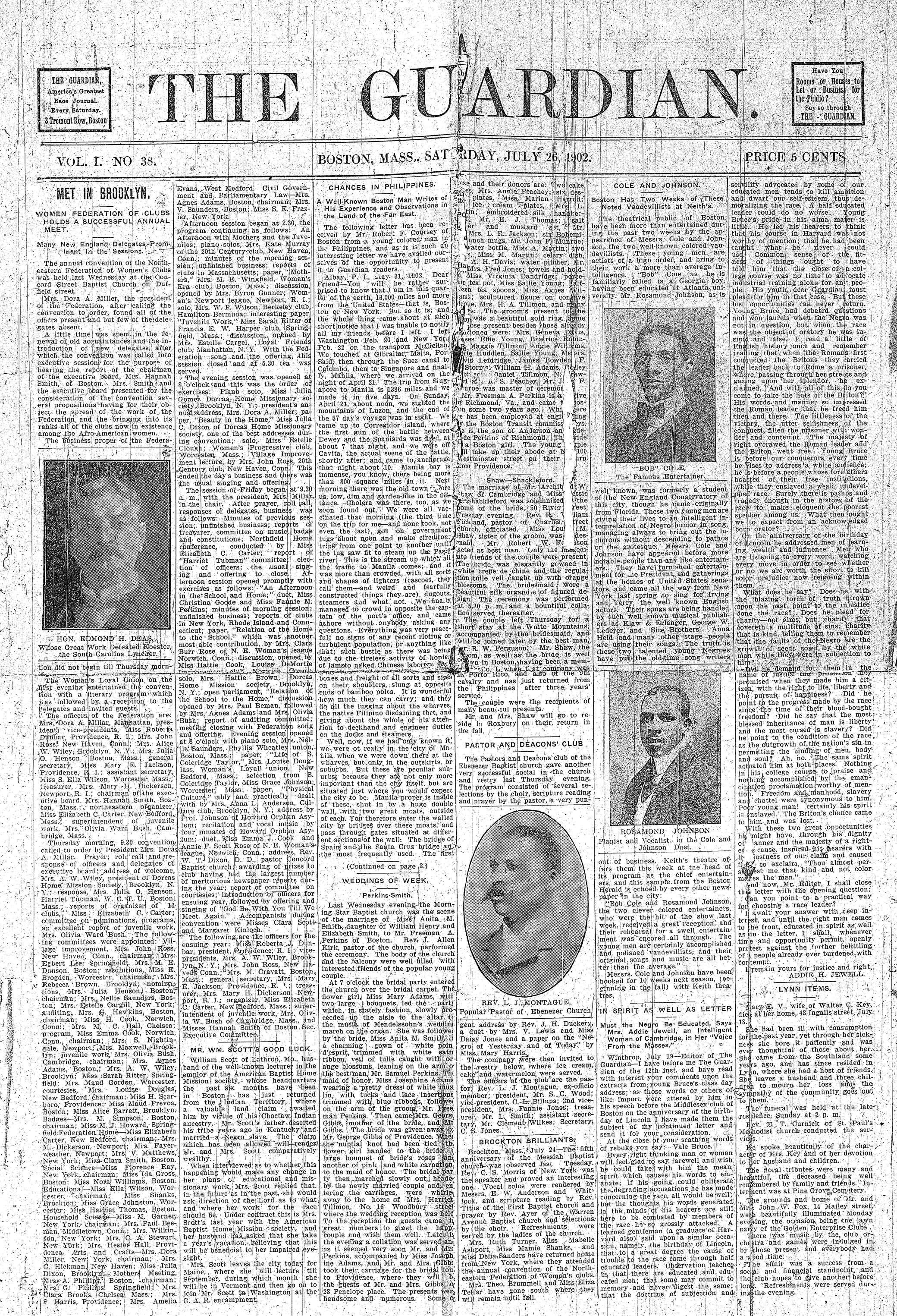

Front page of the Guardian, July 26, 1902. Center for Research Libraries.

In 1900, when William Monroe Trotter explored the possibility of creating a black weekly—what eventually became the Guardian—African Americans in Boston hadn’t had a newspaper of their own since George Forbes and Josephine Ruffin edited the Courant in the early 1890s. Nearly every state with a sizable black community had one by the late 1880s, four- to eight-page publications that transformed their correspondents and editors into local political celebrities who often leveraged their popularity into lucrative political careers in city and state government. T. Thomas Fortune’s New York Age, William Chase’s Colored American, and John Mitchell Jr.’s Richmond Planet—those black newspapers that survived high printing costs and the fickle tastes of the general public—became powerful cultural institutions in black America that promoted cultural exchange across an African diaspora that was either vilified, or ignored, in the white press.

Although they lacked a stable black press, colored Bostonians wrote some of the most influential political essays for black newspapers in Washington, DC, New York, and Philadelphia, a community passion for black news that inspired Fortune to tour the city for donations in 1883 as he transformed the New York Freeman into the New York Age. (Throughout his life, Trotter used the term colored, proudly insisting that it was the only term capable of encompassing all that black Boston represented—the southerners from Baltimore and Raleigh, the cosmopolites from Toronto, Halifax, and London, Cape Verdeans and Bahamians whose lilting accents reverberated through Cambridgeport and the South End.) By the time Trotter graduated from Harvard, however, Boston’s history of playing adjunct to the national colored press meant that even the best-produced weeklies struggled to retain a local audience. Both the Boston Courant and Woman’s Era were the leading black newspapers in New England during the 1890s, but their circulation numbers dropped by 1900. In 1898 financial difficulties forced Forbes out of publishing, while the Woman’s Era was so thoroughly co-opted by the conservative-leaning National Association of Colored Women that it barely registered in New England’s black consciousness.

Then, in 1900, Pauline E. Hopkins’ monthly magazine, the Colored American, appeared in Boston, forever changing the national black press. Like Trotter, Hopkins was a colored Bostonian through and through—her stepfather served in the Union Navy, her maternal New Hampshire ancestor Thomas Paul helped found Boston’s African Baptist Church in 1806, and she grew up in the West End, where her maternal relative Elijah W. Smith was a famous abolitionist poet. By the time Hopkins began writing her first novel, Hagar’s Daughter, in the 1880s, she had already gained national fame for her stage play Peculiar Sam, the first ever written and directed by a black woman. When the play premiered in Boston in 1879, with popular black performers Sam Lucas and the Hyers Sisters, the reception was so great that it eventually toured New York and the Midwest.

With its head-and-shoulder photographs of well-dressed, perfectly coiffed black men and women, its articles by Pan-Africanists and ministers alike, and its editorials by activist-intellectuals from DC to Chicago, the Colored American was a sophisticated example of radical racial uplift through which the black middle and upper class discussed civil rights. In addition to writing her popular serialized novels, for instance, Hopkins published profiles of black men and women whose contributions to black freedom provided contemporary activists with examples of radical protest. Edwin Walker was profiled in February 1900, while Boston abolitionists John J. Smith and Lewis Hayden received full-page biographies linking their “fight against slavery” to the present demand for “manhood rights.”

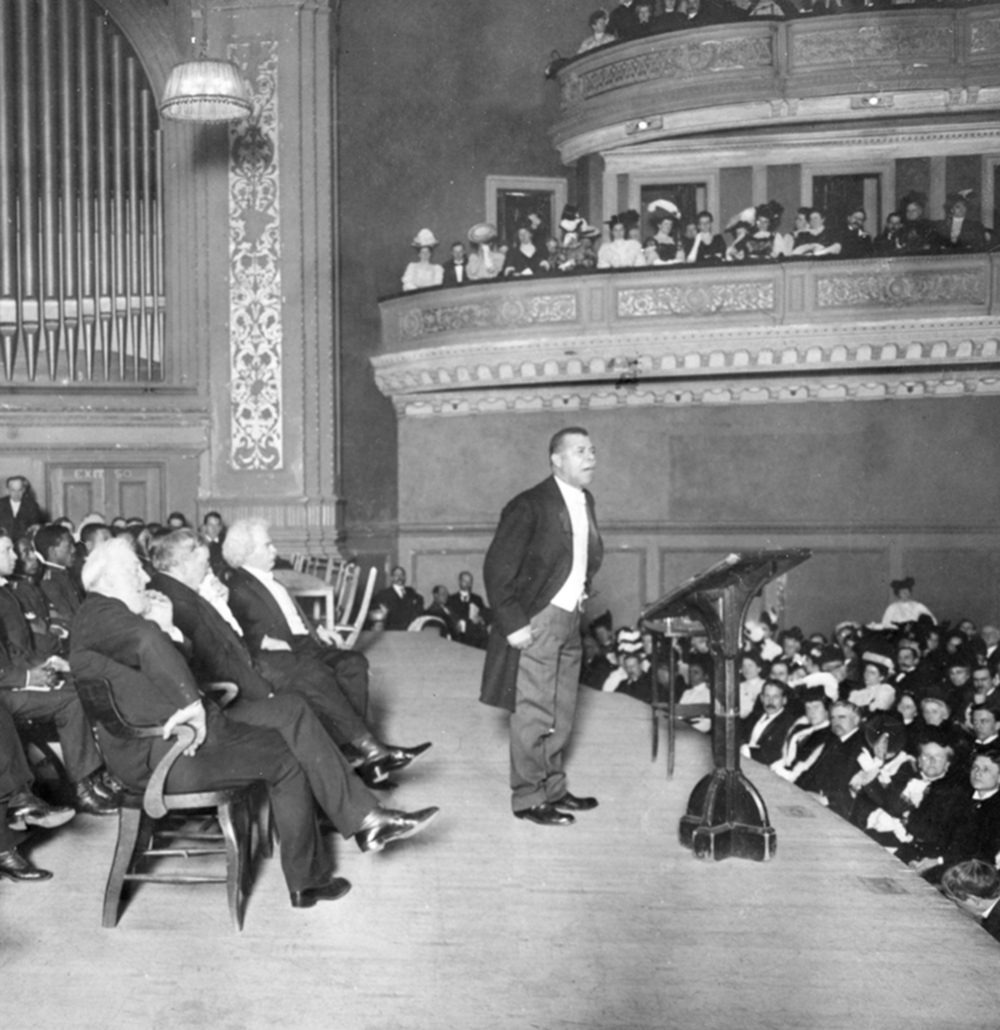

As an intellectually engaged monthly that produced literature and poetry alongside political treatises on segregation and disenfranchisement, the Colored American implicitly challenged Booker T. Washington’s control on the black press. And this challenge was desperately needed, since the Tuskegee president’s co-optation of black newspapers from Mississippi to DC meant that black dissent was ruthlessly stifled. This was particularly true when such dissent criticized either the Republican Party or the industrial education philosophy preached by Tuskegee.

Most American weeklies were controlled, to some extent, by one of the political parties, which often bankrolled cheap newspapers during local election cycles, only to withdraw payment after the cycle ended. As the infamous “Wizard of Tuskegee” who used racial accommodation as a political tool, Washington was no different from white politicians of his time, secretly subsidizing black newspapers across the country and crushing those editors who refused to be bought. By 1900, like William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer, Washington managed to subsidize nearly all the black weeklies in the country, including Fortune’s previously “negrowump” New York Age. (Fortune identified negrowumpism as a form of radical racial uplift that bound “leading, progressive” northern blacks to the full racial equality, and economic justice, of their fellows across the country; it was an idea that became the basis for much of Trotter’s politics.)

In addition to control of radical dissent through subsidization of the “negro press,” Washington and his fellow racial conservatives hijacked the previously negrowump Afro-American League, one of the first national civil rights organizations of the postbellum era. Boston radicals grew increasingly frustrated by what Trotter called “the strangling of colored dissent.” With the country’s only national, black-led civil rights organization beholden to Washington, and with the press under Tuskegee’s control, Trotter believed that black citizens were being “duped into their own enslavement.” A “colored weekly,” published by radicals and independent of “so-called colored leaders,” created an opportunity for colored people to resist “their own enslavement” outside the confines of conservative institutions. If all vehicles of black politics subscribed, uncritically, to conservative racial uplift, Trotter worried, then colored people could never reclaim their civil rights.

Thus, from the beginning, Trotter’s new weekly, the Guardian, showed its audience the real-life consequences, without pretense, of white supremacy, federal apathy, and conservative uplift. Unconcerned with the poetry, short stories, and serialized fiction that made the Colored American so unique, the Guardian dealt with what its editors called “the truth.” Like the muckrakers Ida Tarbell and Ray Stannard Baker, who were concerned with using the press to expose institutional abuses of the era, Trotter and Forbes wanted to “hold a mirror up to nature.” They aimed to do this by agitating for racial revolution and exposing the damage wrought by both accommodation to white supremacy and Republican neglect of civil rights. As Trotter said in a letter to his former roommate John Fairlie less than a year into his editorship, “I have at last become so washed down and alarmed by the growth of caste feeling and caste laws, and so angered at Booker Washington’s betrayal of colored people and so indignant at the Boston Herald and Transcript for smothering all those who wished to condemn him that I have founded a newspaper of my own in partnership with a friend named Forbes.” For Trotter, the Guardian was an “arsenal,” which meant that he and Forbes stood on the “firing line” in a war for civil rights in which conservative Americans, black and white, refused to engage. “I can now feel,” he concluded, “that I am doing my duty and trying to show the light to those in darkness and to keep them from at least being duped into helping in their own enslavement.”

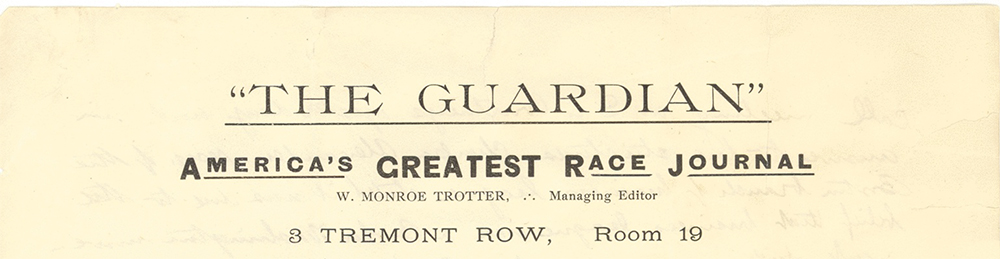

Trotter and Forbes set up their printing office on Tremont Row in the heart of Boston’s mercantile and publishing center, a decision that physically claimed radical abolition as the foundation for his “arsenal.” Tremont Row was the former home of William Lloyd Garrison’s Liberator, where young colored militants like William C. Nell first set type for speeches by Frederick Douglass, Maria Stewart, and Charles Lenox Remond. Over the years, Trotter kept a bust of Garrison on his desk, along with sketches of radical colored heroes from his childhood, like John Mercer Langston and P.B.S. Pinchback. In setting up his “firing line” on Tremont Row, Trotter and the Guardian were a constant presence in the heart of New England’s all-white publishing industry. Tremont Row was located downtown, a block from the Boston Common and the state house, and a train ride on Boston’s El to the tenement and boarding houses south of the Back Bay where blacks had begun to migrate during the 1880s. Housing and employment discrimination might keep colored Bostonians away from the gatekeepers of public opinion, but the Guardian’s presence mere blocks from the Boston Globe, the Herald, and the Transcript ensured that their political fight could not be ignored.

The Guardian’s presence at the nucleus of Boston culture and politics placed Trotter’s revival of radical racial uplift at the metaphorical dividing line between black Boston’s future in the South End and its past on the North Slope of Beacon Hill. Ten years later, when South End Settlement House founder Robert Woods wrote his famous study on “the Boston Negro,” the black community’s transfer from Smith Court, Belknap, and Cambridge Streets in the West End to Albany, Kendall, and Hemenway Streets on the border of Lower Roxbury, was nearly complete. Although some black families remained in the West End—most notably Josephine Ruffin, whose Cambridge Street house remained a center of black college life well into the early 1900s—Trotter and Forbes were smart enough to recognize that colored Boston was changing, despite their determination to connect their present civil rights struggle with antebellum abolition.

And the changes to black Boston were profound by 1901. That year, as Trotter founded the Guardian, future black Boston leader Melnea Jones Cass arrived on Hemenway, then moved to Kendall Street, from her native Richmond. Like most black migrants, the Jones family was driven to Boston after a maternal aunt, Ella Drew, made the journey first and told them of the opportunities that existed in a city with no legal segregation, integrated public education, and higher wages. On Kendall Street, a few blocks down from the bucolic setting that Lieutenant Trotter moved to in 1869, the Joneses lived on the first floor of a brick building that had once been a single-family home. Two other families lived above them, and the kitchen was in the basement, looking out to a yard that Cass remembered as “beautiful” despite its urban setting.

Although the family did not make a lot of money, they were typical of many southern migrants in the city. Hard working and determined to give their children better opportunities, Albert and Mary Jones had “good educations for people at that time…They weren’t getting any place [in Richmond]…and they weren’t making any progress there.” Although Melnea’s father worked as a janitor, and her mother was a domestic, she and her sisters knew the South End as much more than the “slum” in which leaders of the Social Gospel built settlement houses. Cared for by neighbors during the day after their mother died, Melnea and her sister were eventually transported to Newburyport, a seaside community where the good public schools provided opportunities they could not have dreamed of in Virginia.

As an editor on Tremont Row, outside of this working-class yet ambitious black South End community, Trotter had to create a newspaper that attracted readers like the Joneses. If his mission was to “hold a mirror up to nature,” and prevent black people from “being duped into their own enslavement,” he had to directly inspire a community whose immediate needs were underrepresented in the monthly literature, poetry, and political editorials provided by Hopkins’ Colored American. After all, the people who read and contributed to the magazine were much like Hopkins and Trotter—professional, middle- and upper-class colored people for whom abolition, postbellum political independence, and civil rights activism had been de rigueur since childhood.

This audience, however, was a minority in 1900. Although black Boston still had the highest literacy rates and largest percentage of black professional of any black community in the country in 1900, the influx of colored southerners and Caribbean migrants, and rampant employment discrimination, meant that the employment discrimination, segregation, and poverty that Trotter’s father witnessed during the 1870s had barely changed by the time Trotter set up the Guardian in 1901. While their employment status and income did not preclude working-class colored citizens’ attraction to the Colored American’s highbrow literature, they were the ones most adversely affected by conservative policies of disenfranchisement and segregation. Their immediate need, then, was an unabashed, overly political weekly that inspired them to challenge the racial status quo.

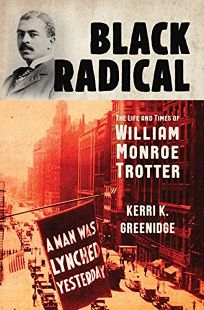

Adapted from Black Radical: The Life and Times of William Monroe Trotter. Copyright © 2019 by Kerri K. Greenidge. Used with permission of the publisher, Liveright Publishing Corporation, a division of W.W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.