Extraordinary how potent cheap music is.

—Noël Coward, 1930Hold the Applause

Claude Debussy, dilettante hater.

Monsieur Croche was a spare, wizened man, and his gestures were obviously suited to the conduct of metaphysical discussions; his features are best pictured by recalling those of Tom Lane, the jockey, and Monsieur Thiers. He spoke almost in a whisper and never laughed, occasionally enforcing his remarks with a quiet smile which, beginning at his nose, wrinkled his whole face, like a pebble flung into still waters, and lasted for an intolerably long time.

He aroused my curiosity at once by his peculiar views on music. He spoke of an orchestral score as if it were a picture. He seldom used technical words, but the dimmed and slightly worn elegance of his rather unusual vocabulary seemed to ring like old coins. I remember a parallel he drew between Beethoven’s orchestration—which he visualized as a black-and-white formula resulting in an exquisite gradation of grays—and that of Wagner, a sort of many-colored “makeup” spread almost uniformly, in which, he said, he could no longer distinguish the tone of a violin from that of a trombone.

Since his intolerable smile was especially evident when he talked of music, I suddenly decided to ask him what his profession might be. He replied in a voice that checked any attempt at comment, “Dilettante hater.” Then he went on monotonously and irritably, “Have you noticed the hostility of a concert-room audience? Have you studied their almost drugged expression of boredom, indifference, and even stupidity? They never grasp the noble dramas woven into the symphonic conflict in which one is conscious of the possibility of reaching the summit of the structure of harmony and breathing there an atmosphere of perfect beauty. Such people always seem like guests who are more or less well-bred. They endure the tedium of their position with patience, and they remain only because they wish to be seen taking their leave at the end. Otherwise, why come? You must admit that this is a good reason for an eternal hatred of music.”

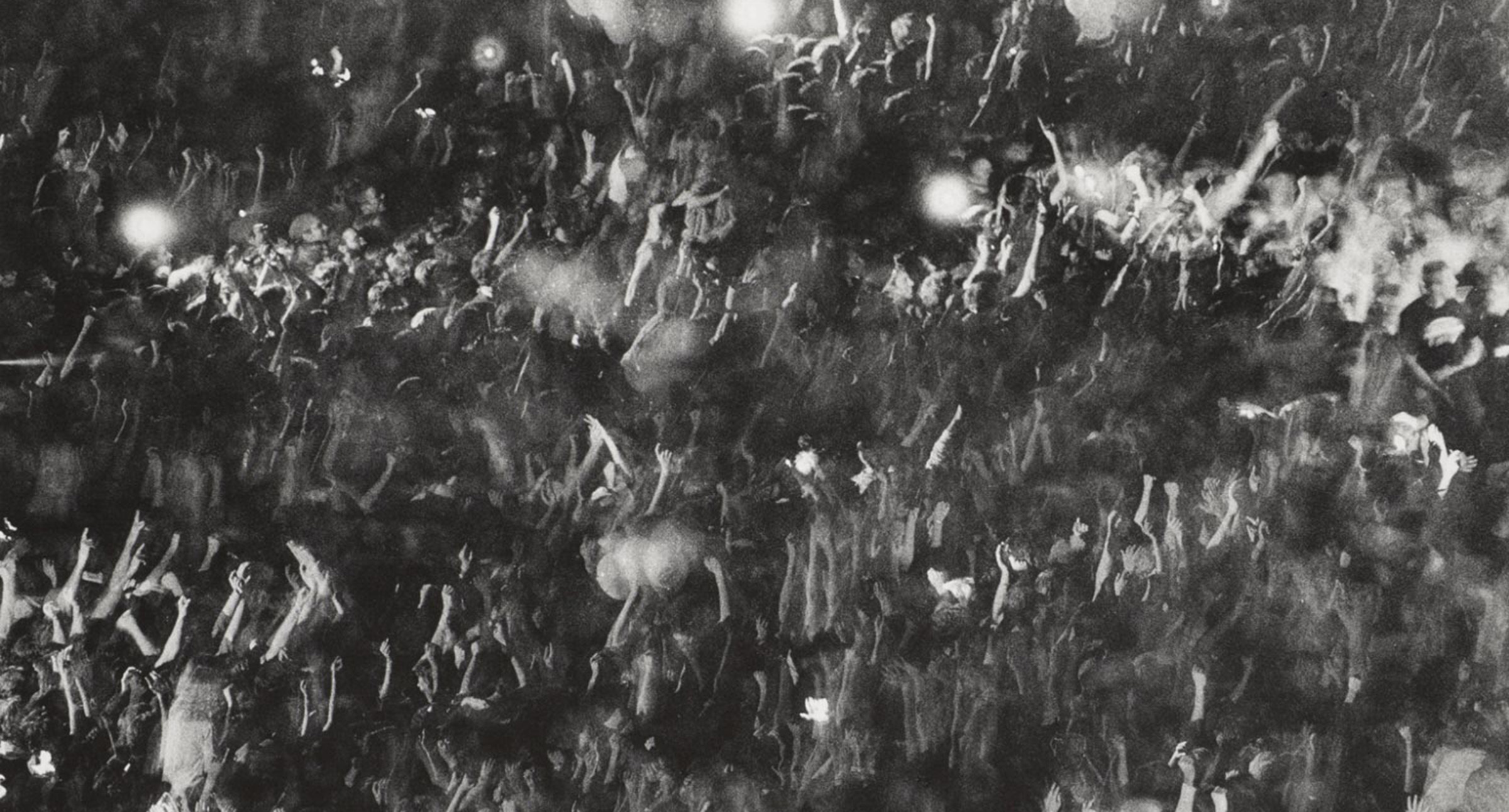

Rolling Stones Concert, New Orleans, by Burk Uzzle, 1982. © Philadelphia Museum of Art, purchased with the Lola Downin Peck Fund and with funds contributed by Mr. and Mrs. John Medveckis, Douglas Mellor, Ross Watson, and other donors, 1984.

I argued that I had observed and had even shared in highly commendable displays of enthusiasm. To which he answered, “You are greatly in error. For if you showed so much enthusiasm, it was with the secret hope that some day a similar honor would be paid to you. Surely you know that a genuine appreciation of beauty can only result in silence? Tell me, when you see the daily wonder of the sunset, have you ever thought of applauding? Yet you will admit that it is a rather more unrehearsed effect than all your musical trifles. Moreover, face-to-face with the sunset, you feel so mean a thing that you cannot become a part of it. But before a so-called work of art, you are yourself and you have a classical jargon that gives you an opportunity for eloquence.”

I dared not confess how nearly I agreed with him, since nothing withers conversation like agreement. I preferred to ask if he himself played any instrument. He raised his head sharply and replied, “I dislike specialists. Specialization is for me the narrowing of my universe. It reminds me of those old horses who, in bygone days, worked the roundabouts and died to the well-known strains of the ‘Marche Lorraine’! Nevertheless, I know all music, and it has only given me a special pride in being safe from every kind of surprise. Two bars suffice to give me the clue to a symphony, or to any other musical incident.

“Though we may be certain that some great men have a stubborn determination always to break fresh ground, it is not so with many others, who do nothing but repeat the thing in which they have once succeeded. Their skill leaves me cold. They have been hailed as masters. Beware lest this be not a polite method of getting rid of them or of excusing the sameness of their performances. In short, I try to forget music because it obscures my perception of what I do not know or shall only know tomorrow. Why cling to something one knows too well?

“Music is a sum total of scattered forces. You make an abstract ballad of them! I prefer the simple notes of an Egyptian shepherd’s pipe, for he collaborates with the landscape and hears harmonies unknown to your treatises. Musicians listen only to the music written by cunning hands, never to that which is in nature’s script. To see the sun rise is more profitable than to hear the Pastoral Symphony. What is the use of your almost incomprehensible art? Ought you not to suppress all the parasitic complexities, which make music as ingenious as the lock of a strongbox? You paw the ground because you only know music and submit to strange and barbarous laws. You are hailed with high-sounding praises, but you are merely cunning! Something between a monkey and a lackey.”

Claude Debussy

From “Monsieur Croche the Dilettante Hater.” Born into near poverty in 1862, Debussy entered the Paris Conservatory in 1872 and became known for his unorthodox and “impressionist” compositional style—a description he would later come to resent. In 1901 he took a job as music critic for La Revue blanche and invented Monsieur Croche, part nom de plume, part alter ego, to allow him to discuss music aesthetics in dialogue form. Debussy died in 1918; his Monsieur Croche essays were collected and published three years later.