Reconciliation is not about being cozy. It is not about pretending that things were other than they were.

Reconciliation based on falsehood, on not facing up to reality, is not true reconciliation and will not last. We believe we have provided enough of the truth about our past for there to be a consensus about it. There is consensus that atrocious things were done on all sides. We know that the state used its considerable resources to wage a war against some of its citizens. We know that torture and deception and murder and death squads came to be the order of the day. We know that the liberation movements were not paragons of virtue and were often responsible for egging people on to behave in ways that were uncontrollable. We should accept that truth has emerged even though it has initially alienated people from one another. The truth can be, and often is, divisive. However, it is only on the basis of truth that true reconciliation can take place. On the whole, we have been exhilarated by the magnanimity of those who should by rights be consumed by bitterness and a lust for revenge. It is not easy to forgive, but we have seen it happen. And some of those who have done so are white victims. Nevertheless, the bulk of victims have been black, and I have been saddened by what has appeared to be a mean-spiritedness in some of the leadership in the white community. When one confesses, one confesses only one’s own sins, not those of another. When a husband wants to make up with his wife, he does not say, “I’m sorry, please forgive me, but darling of course you, too, have done so-and-so!” That is not the way to reach reconciliation. That is why I still hope that there will be a white leader who will say, “We had an evil system with awful consequences. Please forgive us.” Without qualification. If that were to happen, we would all be amazed at the response.

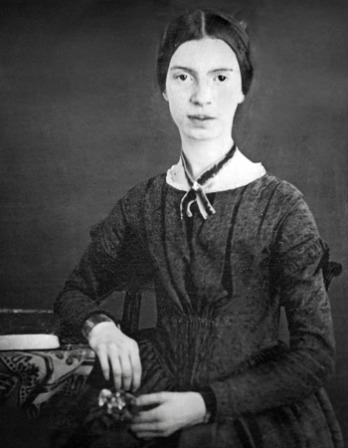

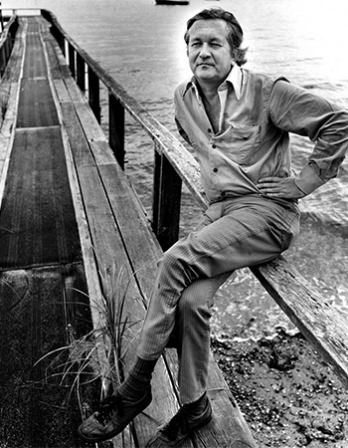

From the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report. Born in 1931, Tutu became the first black archbishop of Cape Town in 1986. Nine years later Nelson Mandela, South Africa’s first democratically elected president, appointed him chair of the seventeen-member commission charged with investigating human-rights violations perpetrated during apartheid and negotiating amnesty agreements with, rather than punishing, the perpetrators. Over the course of its public hearings, the commission received around 22,000 victim statements and 7,000 amnesty applications.

Back to Issue