Drunkenness, sexual irregularities, brutality, and disregard for the rights of property are the chief points with which the bourgeois charges the workers. That they drink heavily is to be expected. Sheriff Alison asserts that in Glasgow some thirty thousand workingmen get drunk every Saturday night, and the estimate is certainly not exaggerated; and that in that city in 1830, one house in twelve, and in 1840, one house in ten, was a public house; that in Scotland, in 1823, excise was paid upon 2,300,000 gallons of spirits; in 1837, upon 6,620,000 gallons; in England, in 1823, upon 1,976,000 gallons, and in 1837, upon 7,875,000 gallons.

The Beer Act of 1830, which facilitated the opening of beer houses (jerry shops), whose keepers are licensed to sell beer to be drunk on the premises, facilitated the spread of intemperance by bringing a beer house, so to say, to everybody’s door. In nearly every street there are several such beer houses, and among two or three neighboring houses in the country, one is sure to be a jerry shop. Besides these, there are hush shops in multitudes, i.e., secret drinking places which are not licensed, and quite as many secret distilleries which produce great quantities of spirits in retired spots, rarely visited by the police, in the great cities. It is estimated that there are more than one hundred of these secret distilleries in Manchester alone, and their product to be at 156,000 gallons at the least. In Manchester there are, besides, more than a thousand public houses selling all sorts of alcoholic drinks, or quite as many in proportion to the number of inhabitants as in Glasgow. In all other great towns, the state of things is the same. When one reflects that many a mother gives the baby on her arm gin to drink, the demoralizing effects of frequenting such places cannot be denied.

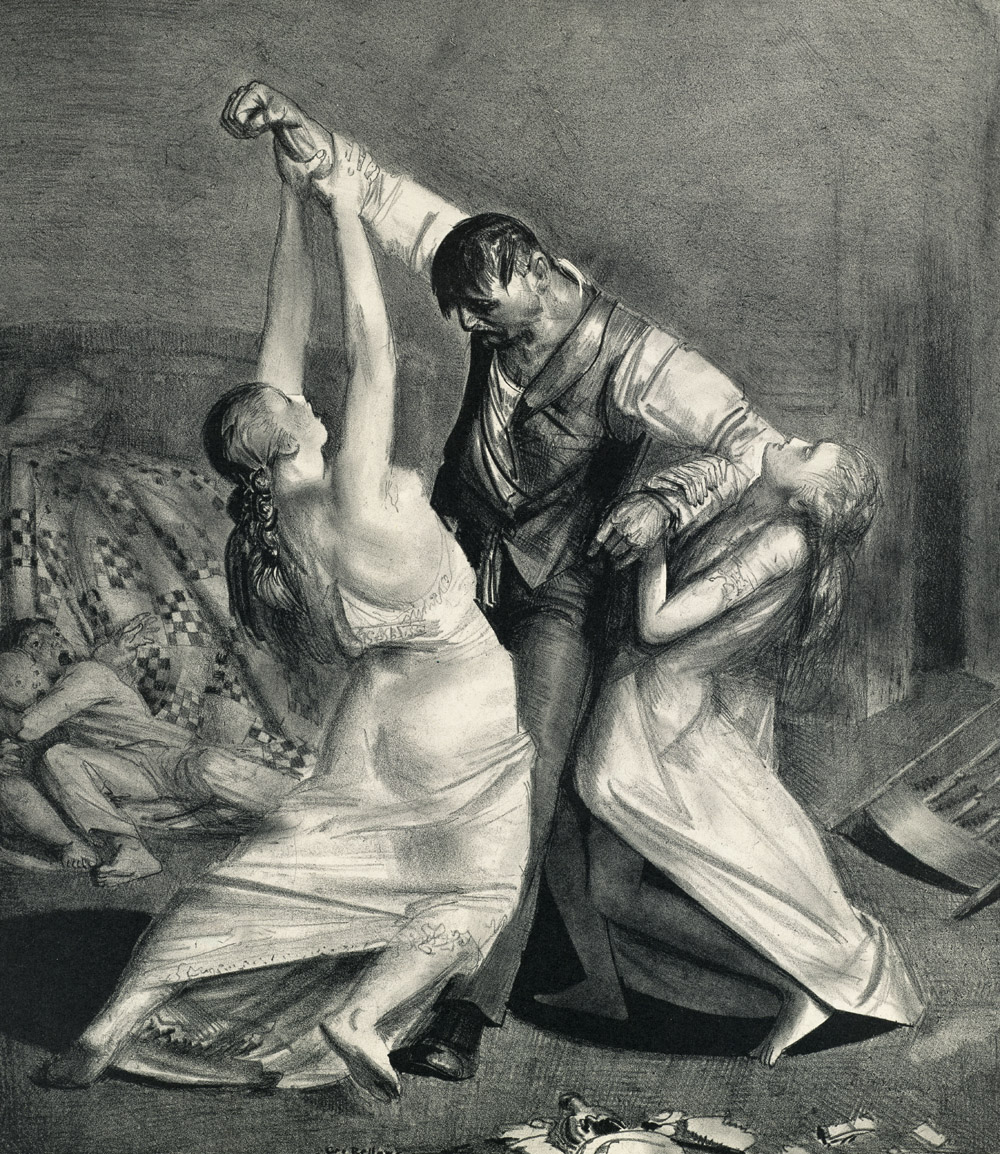

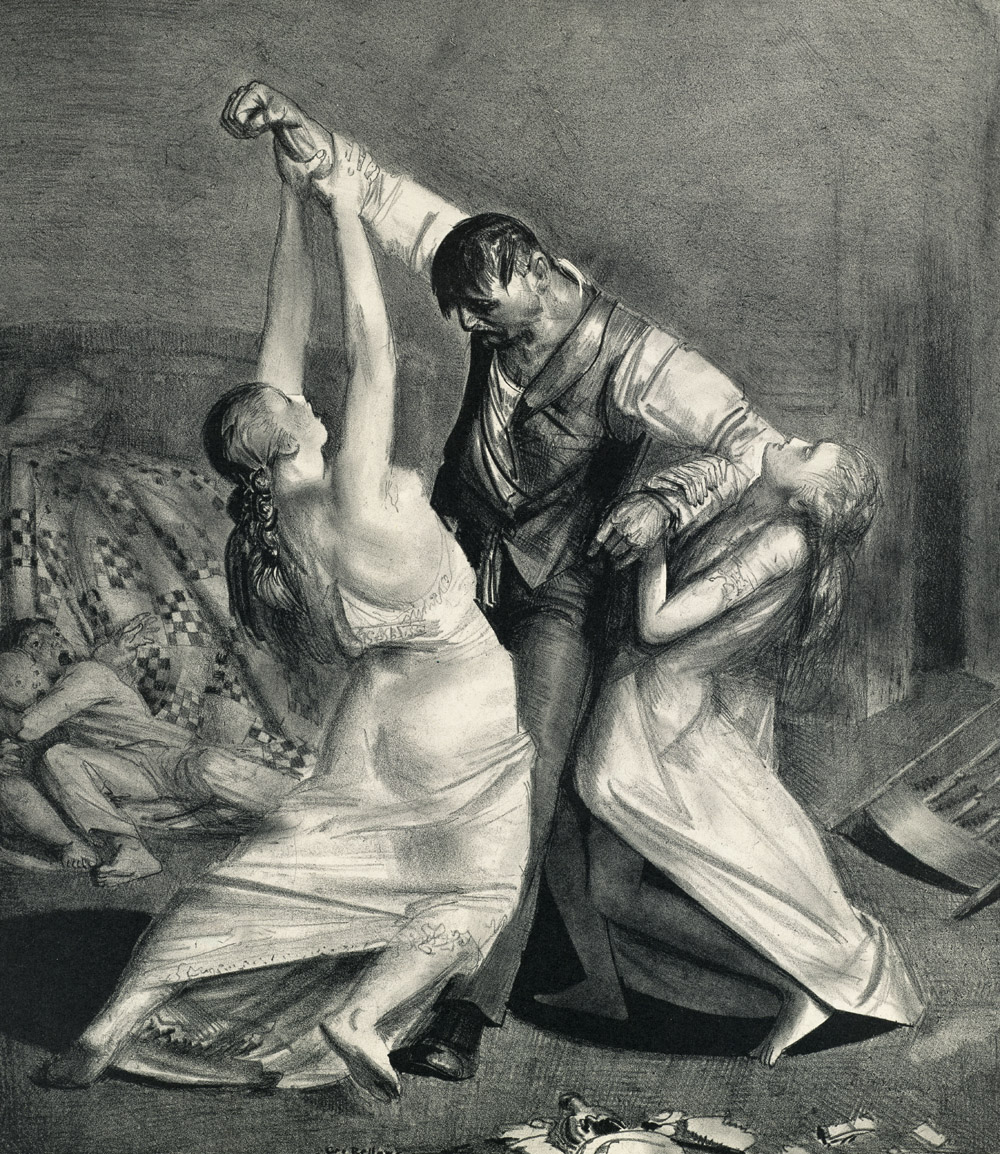

The Drunk, by George Wesley Bellows, c. 1923.

On Saturday evenings, especially when wages are paid and work stops somewhat earlier than usual, when the whole working class pours from its own poor quarters into the main thoroughfares, intemperance may be seen in all its brutality. I have rarely come out of Manchester on such an evening without meeting numbers of people staggering and seeing others lying in the gutter. On Sunday evening the same scene is usually repeated, only less noisily. And when their money is spent, the drunkards go to the nearest pawnshop, of which there are plenty in every city—over sixty in Manchester, and ten or twelve on a single street of Salford, Chapel Street—and pawn whatever they possess. Furniture, Sunday clothes where such exist, kitchen utensils in masses are fetched from the pawnbrokers on Saturday night only to wander back, almost without fail, before the next Wednesday, until at last some accident makes the final redemption impossible, and one article after another falls into the clutches of the usurer, or until he refuses to give a single farthing more upon the battered, used-up pledge. When one has seen the extent of intemperance among the workers in England, one readily believes Lord Ashley’s statement that this class annually expends something like twenty-five million pounds sterling upon intoxicating liquor: and the deterioration in external conditions, the frightful shattering of mental and physical health, the ruin of all domestic relations that follow may readily be imagined. True, the temperance societies have done much, but what are a few thousand teetotalers among the millions of workers? When Father Mathew, the Irish apostle of temperance, passes through the English cities, from thirty to sixty thousand workers take the pledge, but most of them break it again within a month.

From The Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844. Born into a wealthy factory-owning family in 1820, Engels began work as a clerk in an export firm in 1838, writing to his sister two years later, “We now have a complete stock of beer in the office; under the table, behind the stove, and behind the cupboard; everywhere are beer bottles.” During the same year as the revolutions of 1848, Engels coauthored The Communist Manifesto with Karl Marx.

Back to Issue