Life isn’t all beer and skittles, but beer and skittles, or something better of the same sort, must form a good part of every Englishman’s education.

—Thomas Hughes, 1857The Vision Thing

Pope Urban II summons the armies of the Lord.

“Go,” Pope Urban II said to the crowd, “In expiation of your sins, and go assured that after this world shall have passed away, imperishable glory shall be yours in the world that is to come.”

The enthusiasm could not be restrained, and loud shouts interrupted the speaker; the people exclaiming as if with one voice, “Dieu le veult! Dieu le veult!” With great presence of mind Urban took advantage of the outburst, and as soon as silence was obtained continued, “Dear brethren, today is shown forth in you that which the Lord has said by his Evangelist, ‘When two or three are gathered together in my name, there will I be in the midst of them to bless them.’ If the Lord God had not been in your souls, you would not all have pronounced the same words, or rather God himself pronounced them by your lips, for it was he who put them in your hearts. Be they, then, your war cry in the combat, for those words came forth from God. Let the army of the Lord, when it rushes upon his enemies, shout but that one cry, ‘Dieu le veult! Dieu le veult!’ Let whoever is inclined to devote himself to this holy cause make it a solemn engagement and bear the cross of the Lord either on his breast or his brow till he set out, and let him who is ready to begin his march place the holy emblem on his shoulders, in memory of that precept of our Savior, ‘He who does not take up his cross and follow me is not worthy of me.’”

For several months after the Council of Clermont, France and Germany presented a singular spectacle. The pious, the fanatic, the needy, the dissolute, the young and the old, even women and children, and the halt and lame, enrolled themselves by hundreds. In every village the clergy were busied in keeping up the excitement, promising eternal rewards to those who assumed the red cross, and fulminating the most awful denunciations against all the worldly minded who refused or even hesitated. Every debtor who joined the Crusade was freed by papal edict from the claims of his creditors; outlaws of every grade were made equal with the honest upon the same conditions. The property of those who went was placed under the protection of the Church, and St. Paul and St. Peter themselves were believed to descend from their high abode to watch over the chattels of the absent pilgrims. Signs and portents were seen in the air, to increase the fervor of the multitude. An aurora borealis of unusual brilliancy appeared, and thousands of the Crusaders came out to gaze upon it, prostrating themselves upon the earth in adoration. It was thought to be a sure prognostic of the interposition of the Most High, and a representation of his armies fighting with and overthrowing the infidels. Reports of wonders were everywhere rife. A monk had seen two gigantic warriors on horseback, the one representing a Christian and the other a Turk, fighting in the sky with flaming swords, the Christian of course overcoming the pagan. Myriads of stars were said to have fallen from heaven, each representing the fall of a pagan foe. It was believed at the same time that the Emperor Charlemagne would rise from the grave and lead on to victory the embattled armies of the Lord. A singular feature of the popular madness was the enthusiasm of the women. Everywhere they encouraged their lovers and husbands to forsake all things for the Holy War. Many of them burned the Sign of the Cross upon their breasts and arms and colored the wound with a red dye as a lasting memorial of their zeal. Others, still more zealous, impressed the mark by the same means upon the tender limbs of young children and infants at the breast.

During the spring and summer of the following year, the roads teemed with crusaders, all hastening to the towns and villages appointed as the rendezvous of the district. Some were on horseback, some in carts, and some came down the rivers in boats and rafts, bringing their wives and children, all eager to go to Jerusalem. Very few knew where Jerusalem was. Some thought it fifty thousand miles away, and others imagined that it was but a month’s journey; while at sight of every town or castle the children exclaimed, “Is that Jerusalem? Is that the city?” Parties of knights and nobles might be seen traveling eastward and amusing themselves as they went with the knightly diversion of hawking to lighten the fatigues of the way.

The theologian and chronicler Guibert de Nogent says the enthusiasm was so contagious that when anyone heard the orders of the pontiff, he went instantly to solicit his neighbors and friends to join with him in “the way of God,” for so they called the proposed expedition. The Palatine counts were full of the desire to undertake the journey, and all the inferior knights were animated with the same zeal. Even the poor caught the flame so ardently that no one paused to think of the inadequacy of his means, or to consider whether he ought to yield up his farm, his vineyard, or his fields. Each one set about selling his property at as low a price as if he had been held in some horrible captivity and sought to pay his ransom without loss of time. Those who had not determined upon the journey joked and laughed at those who were thus disposing of their goods at such ruinous prices, prophesying that the expedition would be miserable and their return worse. But they held this language only for a day; the next they were suddenly seized with the same frenzy as the rest. Those who had been loudest in their jeers gave up all their property for a few crowns and set out with those they had so laughed at a few hours before. In most cases the laugh was turned against them, for when it became known that a man was hesitating, his more zealous neighbors sent him a present of a knitting needle or a distaff to show their contempt of him. There was no resisting this, so that the fear of ridicule contributed its fair contingent to the armies of the Lord.

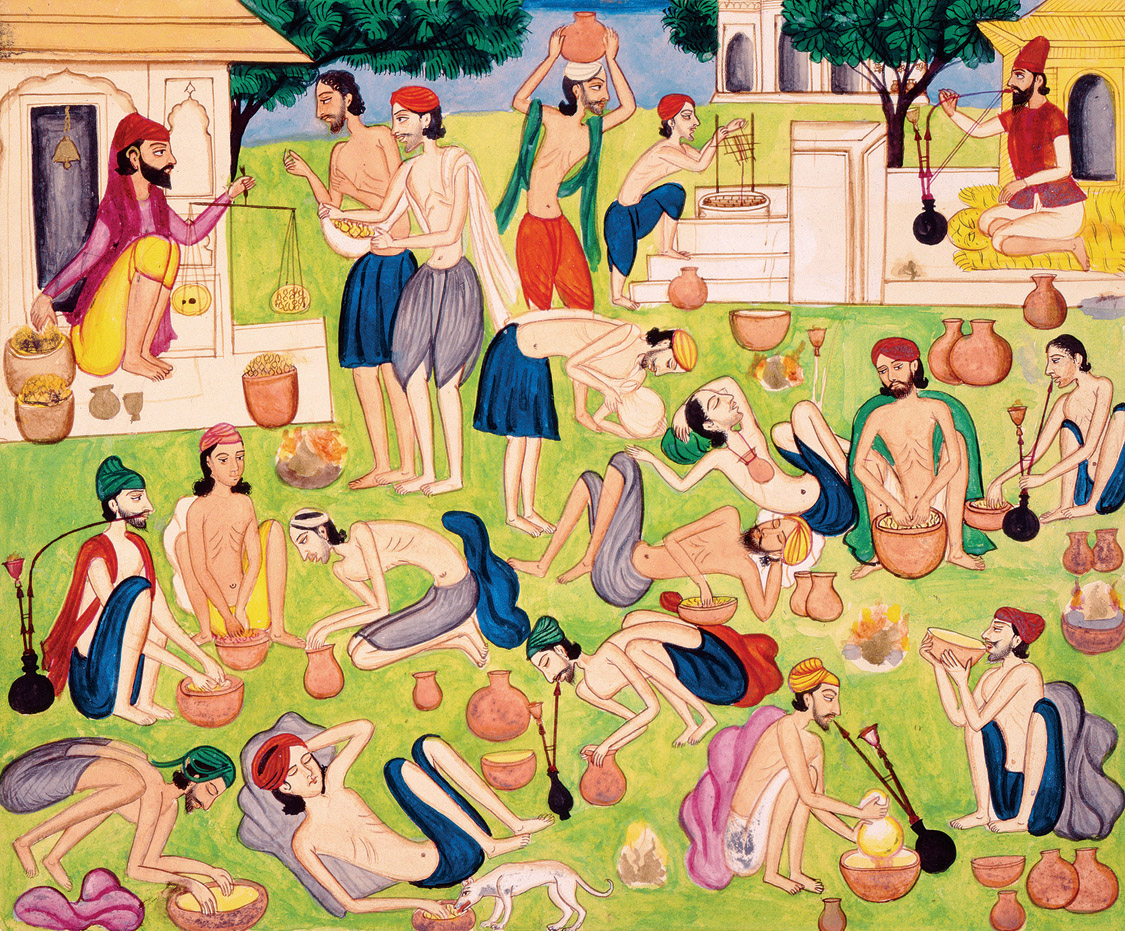

Depiction of the manufacturing and use of narcotics, Punjab, India, c. 1870. © British Library Board. Bridgeman Images.

The encampments of these heterogeneous multitudes offered a singular aspect. Those vassals who ranged themselves under the banners of their lord erected tents around his castle, while those who undertook the war on their own account constructed booths and huts in the neighborhood of the towns or villages preparatory to their joining some popular leader of the expedition. The meadows of France were covered with tents. As the belligerents were to have remission of all their sins on their arrival in Palestine, hundreds of them gave themselves up to the most unbounded licentiousness. The courtesan, with the red cross upon her shoulders, plied her shameless trade with sensual pilgrims without scruple on either side; the lover of good cheer gave loose rein to his appetite, and drunkenness and debauchery flourished. Their zeal in the service of the Lord was to wipe out all faults and follies, and they had the same surety of salvation as the rigid anchorite. This reasoning had charms for the ignorant, and the sounds of lewd revelry and the voice of prayer rose at the same instant from the camp.

Charles Mackay

From Memoirs of Extraordinary Popular Delusions. Although the council met to discuss ecclesiastical reform, it concluded with Pope Urban II’s speech imploring French knights to rescue the Holy Land. His call to arms exists now in five major versions by different writers—a crusader, a monk, an archbishop, an abbot, and a priest. A Scottish poet, songwriter, novelist, and newspaperman, Mackay observed in his 1841 study of crowds and madness, “Every age has its peculiar folly.”