Last season was a strange one in my garden, notable not only for the unseasonably cool and wet weather—the talk of gardeners all over New England—but also for its climate of paranoia. One flower was the cause: a tall, breathtaking poppy, with silky scarlet petals and a black heart, the growing of which, I discovered rather too late, is a felony under state and federal law. Actually it’s not quite as simple as that. My poppies were, or became, felonious; another gardener’s might or might not be. The legality of growing opium poppies (whose seeds are sold under many names, including the breadseed poppy, Papaver paeoniflorum, and, most significantly, Papaver somniferum) is a tangled issue, turning on questions of nomenclature and epistemology that it took me the better part of the summer to sort out.

It started out if not quite innocently, then legally enough. Or at least that’s what I thought back in February, when I added a couple of poppy varieties (P. somniferum as well as P. paeoniflorum and P. rhoeas) to my annual order of flowers and vegetables from the seed catalogs. But the state of popular (and even expert) knowledge about poppies is confused, to say the least; mis- and even disinformation is rife. I’d read in Martha Stewart Living that “contrary to general belief, there is no federal law against growing P. somniferum.” Before planting, I consulted my Taylor’s Guide to Annuals, a generally reliable reference that did allude to the fact that “the juice of the unripe pod yields opium, the production of which is illegal in the United States.” But Taylor’s said nothing worrisome about the plants themselves. I figured that if the seeds could be sold legally (and I found somniferum on offer in a half-dozen well-known catalogs, though it was not always sold under that name), how could the obvious next step—i.e., planting the seeds according to the directions on the packet—possibly be a federal offense? Were this the case, you would think there’d at least be a disclaimer in the catalogs.

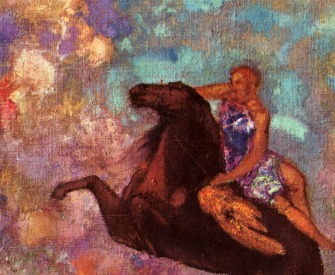

Winter is when the gardener reads and dreams and draws up schemes for the borders he will plant come spring, and the more I read about what the ancient Sumerians had called “the flower of joy,” the more intriguing the prospect of growing poppies in my garden became, aesthetically as well as pharmacologically. I drifted to the mainstream garden writers, many of whom wrote extravagantly of opium poppies—of their ephemeral outward beauty (for the blooms last but a day or two) and their dark inward mystery.

“Poppies have cast a spell over gardeners and artists for many centuries,” went one typical garden writer’s lead; this was, inevitably, quickly followed by the phrase “dark connotations of the opium poppy.” But nowhere in my reading did I find a clear statement that planting P. somniferum would put a gardener on the wrong side of the law. “When grown in a garden,” one authority on annuals declared, somewhat ambiguously, “the cultivation of P. somniferum is a case of Honi soit qui mal y pense. [Shame to him who thinks evil of it.]” In general the garden writers tended to ignore or gloss over the legal issue and focus instead on the beauty of somniferum, which all concurred was exquisite.

Late in May, a friend who knew of my new horticultural passion sent me a newspaper clipping that briefly stopped me in my tracks. It was a gardening column by C. Z. Guest in the New York Post that carried the headline “Just Say No to Poppies.” Guest wrote that although opium poppy seeds are legal to possess and sell, “The live plants (or even dried, dead ones) fall into the same legal category as cocaine and heroin.” This seemed very hard to believe, and the fact that the source was a socialite writing in a tabloid not known for its veracity made me inclined to disregard it.

But I guess my confidence had been undermined, because I decided it wouldn’t hurt to make sure Guest was wrong. I put in a call to the local barracks of the state police. Without giving my name, I told the officer who answered the phone that I was a gardener here in town and wanted to double-check that the poppies in my garden were legal.

“Poppies? Not a problem. Poppies have been declared a flower.”

I told him the ones I had planted were labeled somniferum, and that a neighbor had told me that that meant they were opium poppies.

“What color are they? Are they orange?” This didn’t seem especially relevant; I’d read that opium poppies could be white, purple, scarlet, lavender, and black, as well as a reddish-orange. I told him that mine were both lavender and red.

“Those are not illegal. I’ve got the orange ones in my garden. About two feet tall, came with the house. What you’ve got to understand is that all poppies have some opium in them. It’s only a problem if you start to manufacture opium.”

“Like if I slit open a head?”

“Nah, you can cut one of them open and look inside. It’s only if you do it with intent to sell or profit.”

“But what if I had a lot of them?”

“Say you planted two acres of poppies—just for scenery looks? It’s not a problem—until you start manufacturing.”

I was happy to have the state trooper’s okay, but by now a seed of doubt had been planted in my mind.

I called several experienced gardeners, hoping to get a clearer picture of the risk involved. One told me a story about a DEA agent on vacation in Idaho who’d tipped off the county sheriff that poppies were being grown in local gardens; another had heard that the DEA had recently ordered the removal of the poppies growing at Jefferson’s Monticello. (Both stories sounded apocryphal, but they turned out to be true.) I phoned a radio call-in gardening show, asking the resident expert whether I needed to worry about the opium poppies growing in my garden. “I’m not a lawyer,” she said, “but wouldn’t it be a shame if gardeners had to pass up such a magnificent flower?”

No one had heard of an actual bust, and most of the gardeners I spoke to seemed blithely unconcerned when I apprised them of the theoretical peril. Some treated me carefully, as though it was paranoid of me to worry. Dora Galitzki, the horticulturalist who answers the helpline at the New York Botanical Garden tried to reassure me (a bit patronizingly, I thought) by saying that, to her knowledge, there were no “poppy patrols out there.” Wayne Winterrowd, an expert on annuals who’d written “Shame to him who thinks evil of it” of the poppy grower, likened the crime to tearing the tags off pillows and mattresses, another federal offense no one ever seemed to do time for. Laughing off my worries, he offered to send me seeds of a “stunning” jet-black opium poppy he grew in his Vermont garden. He also confirmed (as did a botanist I spoke to later) that “breadseed poppies” as well as P. paeoniflorum and giganteum were botanically no different than P. somniferum. I’d planted a handful of paeoniflorum, and had had no idea what they were—until now.

I took no small comfort in Winterrowd’s mattress-tag analogy, if only because I really did not want to have to rip out my poppies, at least not now. For my first poppy was on the verge of bloom. It was the first week of July when I noticed at the end of one slender, downward-nodding stem a bud the size of a cherry, covered in a soft, hairy down. The bud’s outer covering, or calyx, had split open, and I could see the scarlet petals folded inside, packed as tightly as a parachute. By the following morning the stem had drawn itself up to its full four-foot height and the petals—five deltas of rich red silk freaked with black—had completely unfurled, casting off their calyx and fuming to face the sun. That solitary exquisite bloom was followed the next day by three more equally formidable dabs of pigment, then six, then a dozen, until my poppy patch was a terrific, traffic-stopping blur of color, of a red so red as to be platonic. Now I knew what Robert Browning meant when he spoke of “the poppy’s red effrontery”: this hue was a shout. The lavender blooms of another variety followed a few days later, a cooler but no less pure jolt of color. When the sun stood behind them, toward evening, the petals were as luminous as stained glass.

“It is a pity,” the garden writer Louise Beebe Wilder wrote, “that poppies are in such haste to shed their silken petals and display their crowned seedpods.” Having seen them, I would have to disagree with her, and not only on pharmacological grounds. The poppy’s seedpods are scarcely less arresting than its flowers: swelling blue-green finials poised atop neat round pedestals (called stipes), each pod crowned with an upturned anther like a Catherine wheel. For most of the month of July, my whole poppy patch was alive with interest. All at once and side by side, you had the drooping sleepy buds, the brilliant flags of color, and the stately upright urns of seeds, all set against the same cool backdrop of dusty green foliage. I couldn’t decide what was more beautiful: leaf, bud, flower, or seedpod. I did decide that this poppy patch was as gorgeous as anything I’d ever planted.

My fellow gardeners were making me feel foolish for even thinking of cutting down these flowers; indeed, as I admired my poppies in their full midsummer glory, this unexpectedly lavish gift of nature, it was difficult to credit the notion that they could possibly be illegal—that for the purposes of the law I might just as well be admiring packets of white powder on a table in some dingy uptown drug factory. But this, I knew, was indeed the case. And what a metamorphosis this was!—that an act as ordinary and blameless as the planting of a handful of common and perfectly legal seeds could somehow transport one into the country of criminality.

Yet this was a metamorphosis that required not only the physical seed and water and sunlight but, crucially, a certain metaphysical ingredient too: the knowledge that the poppies I beheld were, in fact, of the genus Papaver and the species somniferum. For although ignorance of the law is never a defense, in the case of poppies, ignorance of botany may be. True, I had planted seeds I knew to be P. somniferum and then blabbed that fact to the world. But what if instead I had planted “breadseed poppies,” or the poppyseeds on a poppyseed bagel? What if I had planted only the P. paeoniflorum I’d ordered, the one I’d had no idea was really somniferum? As I stood there admiring the extravagantly doubled blooms of this poppy, I realized that growing it was no more felonious than growing asters or marigolds—for as long, that is, as I remained ignorant of the fact that this poppy, too, was somniferum. But it’s too late for me now; I know too much. And so, dear reader, do you.

It was precisely this knowledge that inspired the slightly cracked logic behind what I now decided to do. I had not planned to slit even one of my poppies, for fear that it was the step that would take me across the line into criminality. But now I knew I had already taken the fateful step. In for a dime, in for a dollar. I know, this wasn’t even a remotely rational approach to the situation: a slit seedpod in my garden would constitute proof that I knew exactly what kind of poppies I had. Yet that particular summer afternoon, as I stood there alone with my ravishing poppies, in what, after all, was my garden, this logic seemed strangely compelling. So I combed my little stand of poppies for the fattest, most turgid seed head and bent it toward me. Taking the warm, plum-size pod between my thumb and forefinger, I nicked its skin with a thumbnail. After a moment a small bead of milky sap formed on the surface; the wound continued to bleed for a minute or two, the sap darkening perceptibly as it oxidized, and then it slowed, clotting. I dabbed the drop of opium with my forefinger, touched it to my tongue. It was indescribably bitter. The taste lingered on my palate for the rest of the afternoon.

From “Opium Made Easy.” Once writing that he plants “certain things because I want to learn certain things,” Pollan published A Place of My Own: The Education of an Amateur Builder in 1997, The Botany of Desire: A Plant’s-Eye View of the World in 2001, and The Omnivore’s Dilemma: A Natural History of Four Meals in 2006. He currently serves as a professor of journalism at the UC Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism, and his latest book is Food Rules: An Eater’s Manual.

Back to Issue