Time will reveal everything. It is a babbler and speaks even when not asked.

—Euripides, 425 BCApocalypse Now

At the close of the first millennium, it seemed assured that the end of the world was nigh.

By Tom Holland

Christ’s Descent into Hell, style of Hieronymus Bosch, c. 1550–60. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1926.

I was twelve when it first dawned on me that humanity might have no future. It was 1980. The Soviets were in Afghanistan and hourly expected in Poland; Ronald Reagan was on his way to the White House, and Checkpoint Charlie was still in Berlin. As for me, I was at school in Salisbury, a pleasant and sleepy market town in the south of England. Nothing much had happened there since the Middle Ages, when the local citizenry had built a cathedral that still, seven centuries on from its original construction, proudly sported Britain’s tallest spire. A place less on the frontline of the Cold War it might have seemed hard to imagine. It came as quite a shock, then, when a friend of mine, looking to make my flesh creep, solemnly informed me that a secondhand bookshop just beyond the cathedral close was third on the Soviet hit list of UK targets to be nuked.

Quite how he had come by this startling information he neglected to reveal. Today, of course, I do have the odd, faint doubt as to its veracity. At the time, however, I instinctively believed it. Something had dawned on me. My school was positively heaving with children whose parents were in the military. Why? I already knew the answer to that. Salisbury, in addition to its cathedral and the nearby prehistoric monument of Stonehenge, boasted something altogether more twentieth century nearby: the headquarters of Britain’s land forces. Clearly, then, in the event of any nuclear war, it was indeed likely to take a hit. The sudden realization of this, and the seeming imminence of apocalypse with it, lurched and thickened in my stomach. That afternoon, as I sat in the back of my mother’s car, I looked out at the silhouette of the cathedral, as slimline and sublime as it had been ever since the early thirteenth century, and wondered if it would still be there in the year 2000. Would I be there, and my family, and my friends, and humanity—and indeed the planet? Would any of us make it to the twenty-first century?

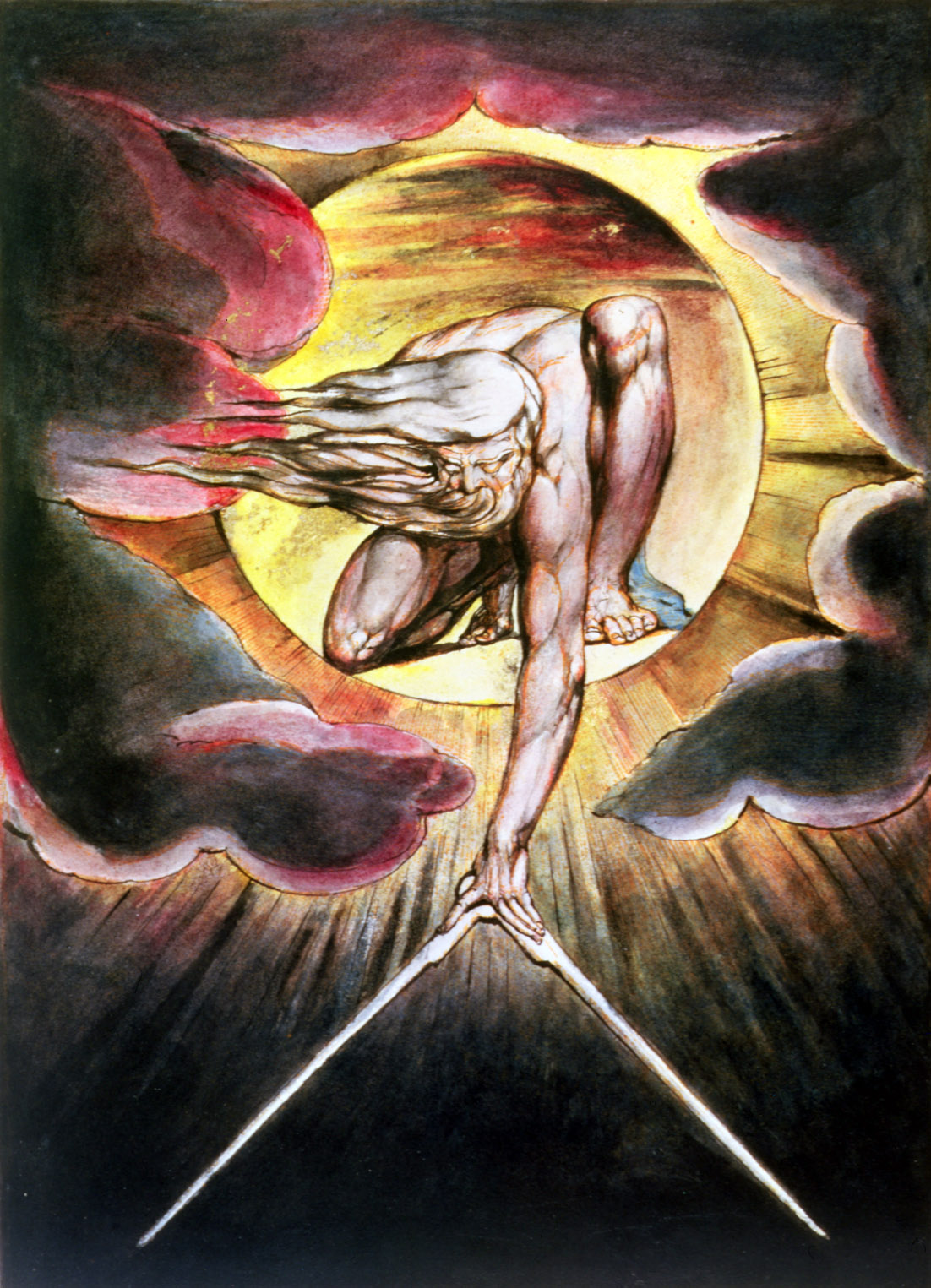

The Ancient of Days, frontispiece for Europe a Prophecy, both by William Blake, 1794. The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

I had not, of course, picked the date 2000 at random. It had a sonorous finality about it. The idea that I might actually be alive in such a year appeared so implausible as to be fantastical. And even if I did it make it, the world around me seemed all too likely to be irradiated, or filled with murderous robots, or ruled by Big Brother—or perhaps all three. Yet if my imaginings of the year 2000 were colored by dread, then so also were they touched by hope. Only make it into the twenty-first century, I used to imagine, only breast that particular tape, and everything would somehow be alright. A paradoxical response, it might be thought, to feel both nervousness and anticipation at the approach of a date; and yet not, I think, a wholly unusual one. The year 2000, when it did finally dawn, was greeted both by hysteria about the possible effects of the Millennium Bug, and by frenzied partying. And then it had come and gone—and nothing much seemed to have changed. The world had not ended, but neither had it entered a golden age. Time just went on—and not for a thousand years would there be another millennium.

Of course, as anyone who has ever suffered a midlife crisis will well appreciate, the feeling that a new age has dawned will always serve to concentrate the mind. To leave a momentous anniversary behind is invariably to be made more sensitive to the very process of change. Living in the shadow of the Cold War, I had prayed that I would live to see the twenty-first century; but now, having crossed that particular threshold, and looking ahead to the future, I find that I am far more conscious than I had ever been before of how infinitely and terrifyingly time stetches, and of how small, by comparison, the span of humanity’s existence is likely to prove. Nor, it seems, am I alone. Intellects much superior to mine evidently feel much the same. “Earth itself may endure, but it will not be humans who cope with the scorching of our planet by the dying sun; nor even, perhaps with the exhaustion of Earth’s resources.” So wrote Martin Rees, Britain’s Astronomer Royal, in a jeremiad cheerily titled Our Final Century: Will Civilization Survive the Twenty-First Century? When James Lovelock, the celebrated environmentalist, first read Rees’ book in 2004, he took it “as no more than a speculation among friends and nothing to lose sleep over”; a bare three years on, and he was gloomily confessing in his own book, The Revenge of Gaia, “I was so wrong.” The current state of alarm about global warming being what it is, even people unfamiliar with Lovelock’s bloodcurdling thesis that the world is on the verge of becoming effectively uninhabitable should be able to guess readily enough what prompted his volte-face. “Our future,” he has written memorably, if chillingly, “is like that of the passengers on a small pleasure boat sailing quietly above the Niagara Falls, not knowing that the engines are about to fail.”

All thoroughly terrifying—and yet, while hardly serving to undermine the case made by Lovelock and his fellow prophets of calamitous climate change, there may just perhaps be some small crumb of comfort to be found in the reflection that we in the Western world, at any rate, have been here once before. A thousand years ago, an abbot in Burgundy, St. Odo of Cluny, drew upon a very similar metaphor to that of Lovelock. The vessel that bore sinful humanity, so Odo warned, was beset all around by a gathering storm surge: “Perilous times are menacing us, and the world is threatened with its end.” His response to the seeming imminence of the End Days was a potent one: to purify himself and the monks he led of all their sins so as to attain the status of angels, and to establish their abbey as a very bulwark of heaven. Meanwhile, out in the world beyond his monastery, other Christians continued to swagger, to thieve, and to slaughter one another with quite as much gusto as ever before. Perhaps, then, remote though the Christians of the first millennium may appear to us, we are never more recognizably their descendants than in our fretful but conflicted attitude toward the future. The sheer range of opinions on global warming, from those, like Lovelock, who fear the worst, to those who dismiss it altogether; the spectacle of anxious and responsible people, perfectly convinced that the planet is indeed warming, nevertheless filling up their cars, heating their houses, and taking cheap flights; the widespread popular presumption, often inchoate but no less genuine for that, that something, somehow, ought to be done: here are reflections, perhaps, that do indeed flicker and twist in a distant mirror.

Indeed, it is no exaggeration to say that the very cast of how we conceptualize the future today was first set for us around the year 1000. Christians had a particular reason to fetishize anything that smacked of a millennial anniversary. The reason for that was to be found in a book that, in the Latin West as opposed to the Greek East, had been enshrined as the very climax of the Bible: the

Revelation of St. John. In this disturbing, gnomic, and incomparably potent text, a vision had been communicated of the End Days, when all the world would be convulsed by unspeakable torments, before the final triumphant return of Christ to judge the living and the dead. One passage in particular was destined to have an incalculable effect upon the fantasies and calculations of the West. In his vision, so John reported, he had seen an angel descend from heaven. “He seized the dragon, that ancient serpent, who is the Devil and Satan, and bound him for a thousand years, and threw him into the pit, and locked and sealed it over him, so that he would deceive the nations no more, until the thousand years were ended.” And for the thousand years of Satan’s imprisonment, until he should once again “be let out for a little while,” to fight the last battle that would see evil defeated once and for all, there would be a rule of saints. Although St. John, typically, had spelled nothing out, there were many readers of Revelation who, in light of this prophecy, identified the binding of Satan with the Resurrection of Christ—meaning, in effect, that the millennial reign of the saints had already begun. No wonder, then, in the Christian imagination, that the number one thousand should have come to possess a particularly haunting purchase.

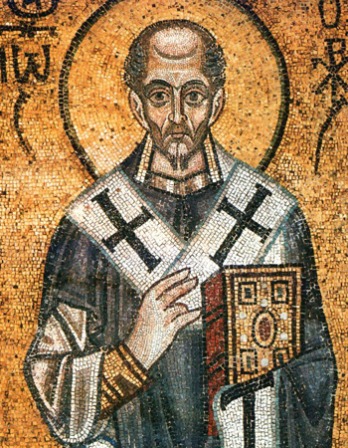

True, the official doctrine of the Church was to deny that St. John’s allusions to a millennium were to be taken literally. Back in the fifth century, even as the collapse of Rome’s empire in the West was prompting many Christians to dread that the End Days were looming, St. Augustine, the great Father of the Latin Church, had scorned the very notion that Revelation might offer a roadmap of the future. St. John, he had insisted, “intended the thousand years to stand for the whole period of this world’s history, signifying the entirety of time by a different number.” This conviction had hardened over the course of the succeeding centuries into a seemingly impregnable orthodoxy. By the tenth century, even as St. Odo of Cluny was warning the faithful to prepare themselves for the hour of judgment, he appears most scrupulous about avoiding any mention of the imminent millennial anniversary of Christ’s birth in his lucubrations. The veil drawn by God across the future was not to be parted by mortal sinners. Even the angels were forbidden to know. The more palpable the proofs that a universal conflagration was at hand, the more strenuously it behooved good Christians, if they were not to be found wanting when Judgment Day did finally arrive, to refrain from adducing the hour.

Inevitably, however, there were many who could not resist the temptation. Nine hundred years and more had passed, after all, since the blessed feet of Christ had walked the earth; and now the thousandth was drawing near. No wonder, then, that there were those even in the ranks of the priesthood who looked at the approaching millennium with a mingled dread and anticipation—and were prepared to admit as much. In one cathedral, for instance, in Paris, there was a preacher who stood up in the presence of the entire congregation and bluntly warned all present that the Antichrist would be upon them “the moment that one thousand years are completed.” A second priest, startled by this dramatic lurch into unorthodoxy, had moved quickly to demolish his colleague’s claim with multiple and learned references to Holy Scripture; but still the prophecies came, “And rumor filled almost all the world.”

Indeed, the impact of these was to be felt across western Christendom. Heresy, a problem that had previously rarely perturbed the Church authorities, all of a sudden, with the imminence of the new millennium, appeared to be spreading everywhere. Only during the End Days, so Christ had admonished, were the weeds to be sorted out from the wheat, “and burned with fire”—and now, it seemed to jumpy churchmen, there were weeds sprouting up everywhere. One monk, nervously marking the times from the watchtower of his monastery in Aquitaine, described the nearby fields and forests of Aquitaine as positively teeming with heretics. Their perverse and devilish strategy was, so this monk reported, to scorn the Church for not being Christian enough. An existence of rough-hewn simplicity, such as the original disciples had known: this was their ideal. In their beginning was to be their end: the heretics, by attempting to found the primitive Church anew in Aquitaine, aimed at nothing less than the hastening of the return of Christ. “They affect to lead their lives as the apostles did.”

Not that it was necessary to be a heretic to be affected by the apocalyptic mood of the age. Against the rugged simplicities of those who sought, beneath trees or out on dusty roads, to lead their lives as the apostles had done, without splendor or ritual, there was arrayed a very different model of sanctity. Foremost in the line of battle was a monk named Odilo, who was heir to Odo as the abbot of Cluny. The piety of the brethren under his authority, the seemingly superhuman continence of their habits, and the angelic beauty of their singing, all combined to suggest that paradise might indeed be created on earth. As the years passed, Cluny’s fame and influence continued to spread. Ever more monasteries came to submit themselves to Odilo’s rule. All were rigorously purified by a program of reform. Once cleansed of every taint of corruption, they stood qualified to serve the Christian people as outposts of heaven. Or so, at any rate, the enthusiasts for reform proclaimed. These, in the shadow of the millennium, extended far and wide. The model of Cluny was coming to have a truly international appeal. The prayers and anthems which were raised there, no matter how scorned they might be by heretics, were increasingly regarded by most Christians as the surest defense that existed against the Devil, and all the horrors that were destined to accompany the End Times.

“Flying Fireman,” color lithograph from the series Visions of the Year 2000, by Jean-Marc Côté, 1899.

Not that the prospect of the Day of Judgment inspired in people dread alone. Indeed, for many—and for the wretched, for the poor, for the oppressed, in particular—the expectation of the world’s imminent end was bred, not of fear, but rather of hope. “It comes, it comes, the Day of the Lord, like a thief in the night!” A warning, certainly, but also a message of joy—and significant, not only for its tone, but for its timing. The man who delivered it, a monk from the Low Countries who in 1012 had been granted a spectacular vision of the world’s end by an archangel, no less, had not the slightest doubt that the Second Coming was at hand. That more than a decade had passed since the millennium itself bothered him not a jot: for although the millennial anniversary of Christ’s birth had provided an obvious focus for apocalyptic expectations, it was not the only, nor even the principal, one. Indeed, far from abating in the wake of its passing, anticipation of Judgment Day seems, if anything, only to have grown over the course of the succeeding thirty-three years—as why, indeed, should it not have done? To the Christian people of that fateful era, as one scholar has expressed it, had been granted a privilege that appeared to them as awesome as it was terrible: “to pass the span of their earthly lives in the very decades marking the thousand-year anniversary of their divine Lord’s intervention into human history.” No wonder, then, at the approach of the millennium of the Passion, that anticipation of the Second Coming should have reached a fever pitch: for what was there, after all, in the entire span of human history that could possibly compare for cosmic significance with Christ’s death, resurrection, and ascension into heaven? Nothing—not even His birth. The true millennium, then, was not the year one thousand. Rather, it was the anniversary of Christ’s departure from the earth He had so fleetingly trodden. An anniversary that fell in or around the year 1033.

No coincidence, then, surely, that the early 1030s should have seen descend from western Europe upon Jersualem “an innumerable multitude, gathered from across the whole world, greater than any man before could have hoped to see.” The heavens, however, remained resolutely empty. Christ did not appear. The end of the world stood postponed, and all those pilgrims who had assembled in such huge numbers on the Mount of Olives found themselves waiting in vain for their Savior’s return. Back in Europe, too, among all who had dared to hope that they might see Him descend in glory and set the world to rights, there was crushing disappointment. Among the poor, whose yearning for a reign of saints the Church had sought to orchestrate as well as temper, the sense of disappointment was especially devastating. The millennium had passed, after all, and the earthly order, by which the strong were set above the weak, had not dissolved.

All progress is based upon a universal, innate desire on the part of every organism to live beyond its income.

Yet if it was the poor who had most cause to feel despair, then they were not alone. Bishops and monks too had yearned to believe in the possibilities of an authentic peace of God: a peace bred not of iron but of love. Now, even if they could not readily admit to it, many found themselves oppressed by a sense of loss. The passage of the years, which previously had struck them as pregnant with mystery and meaning, appeared abruptly leached of both. Time had lost its edge. To a degree unprecedented in the history of the West, the Christian people felt themselves poised on the brink of a new beginning: a sensation that many found disturbing rather than any cause for exhilaration. The past, which had always been valued by them as the surest guide to their future, had suddenly come to appear, in the wake of time’s failure to end, a place remote and alien. In truth, of course, the gulf which separated the new millennium from the wreckage of the old had not opened up overnight. Years, decades, centuries of transformation had served to create a landscape in the West that Augustine would have found unrecognizable. Yet the consciousness of this, the consciousness of change, was indeed something new. “Such is the dispensation of the Almighty—that many things which once existed be cast aside by those who come in their wake.”

So reflected Arnold of Regensburg, a monk from Bavaria who dared in the immediate wake of the millennium’s passing to contemplate the startling possibility that what was to come might indeed be distinct from what had previously been. Evidently a man with a taste for the sensational, Arnold had horizons the very opposite of cloistered. Indeed, on one occasion, sent by his abbot on a mission to Hungary, he had been shadowed by a colossal dragon. His experience of the wilds that lay beyond his monastery certainly seem to have influenced his imagination to a very powerful degree. Arnold disdained the past as a wilderness, one fit to be tamed and cleared, just as the dark forests, with their idol-haunted, corpse-hung groves, had been hacked down by Christian axes to make way for churches and spreading fields. A startling perspective, certainly—and yet less exceptional than it might have been prior to the millennium. “The new should change the old—and the old, if it has no contribution to make to the order of things, should be utterly jettisoned.” There were many, during the feverish and expectant years of the millennium of Christ’s life, who had come to share in this opinion. Nor had the spirit of reform died in 1033. If anything, indeed, the opposite: the failure of Christ to establish His kingdom on earth had left many reformers only all the more determined to do it for Him.

Over the succeeding decades, this sense of mission would serve to transform western Christendom and set it on a course that we can still recognize at work, perhaps, in the far-different world of today. The decades that followed the 1030s were, in the judgment of one celebrated medievalist, a period when the ideals of Christendom, its forms of government, and even its very social and economic fabric “changed in almost every respect.” Here, argued Sir Richard Southern, was the true making of the West. “The expansion of Europe had begun in earnest. That all this should have happened in so short a time is the most remarkable fact in medieval history.” And if remarkable to us, then how much more so, of course, to those who actually lived through it. We in the twenty-first century are habituated to a notion that change can be for the better: the faith that human society, rather than inevitably decaying, can be improved. The men and women of the eleventh century were not. Yet just as the monks of Cluny had believed that by reforming their own souls and bodies they could build a simulacrum of heaven on earth, so would a succession of popes, inspired by their example, increasingly come to aim at the sanctification of the whole of Christendom. The consequences of this soaring ambition were to provide western Europe with its very first experience of revolution. A new ideal would end up enshrined in the very sanctum of what had previously been a profoundly conservative and backward-looking society. An ideal that we today can dimly recognize as being progress.

Such, then, was the future bequeathed to us who live in the twenty-first century by the very different peoples who passed through the first millennium—and it begs some obvious questions. If there are humans still alive in the year 3000, what legacy will we have passed on to them? What great labor of reform will we have undertaken that can rival that attempted by the visionaries of the eleventh century? What future will we have passed on to our heirs?