It was just dark, now. I never went near the house but struck through the woods and made for the swamp. Jim warn’t on his island, so I tramped off in a hurry for the crick and crowded through the willows, red-hot to jump aboard and get out of that awful country—the raft was gone! My souls, but I was scared! I couldn’t get my breath for most a minute. Then I raised a yell. A voice not twenty-five foot from me says, “Good lan’! Is dat you, honey? Doan’ make no noise.”

It was Jim’s voice—nothing ever sounded so good before. I run along the bank a piece and got aboard, and Jim he grabbed me and hugged me, he was so glad to see me. He says, “Laws bless you, chile, I ’uz right down sho’ you’s dead agin. Jack’s been heah, he say he reck’n you’s ben shot, kase you didn’ come home no mo’; so I’s jes’ dis minute a startin’ de raf’ down toward de mouf er de crick, so’s to be all ready for to shove out en leave soon as Jack comes agin en tells me for certain you is dead. Lawsy, I’s mighty glad to git you back agin, honey.”

I says, “All right—that’s mighty good; they won’t find me, and they’ll think I’ve been killed, and floated down the river—there’s something up there that’ll help them think so—so don’t you lose no time, Jim, but just shove off for the big water as fast as ever you can.”

I never felt easy till the raft was two mile below there and out in the middle of the Mississippi. Then we hung up our signal lantern and judged that we was free and safe once more. I hadn’t had a bite to eat since yesterday; so Jim he got out some corn dodgers and buttermilk and pork and cabbage and greens—there ain’t nothing in the world so good, when it’s cooked right—and whilst I eat my supper, we talked and had a good time. I was powerful glad to get away from the feuds, and so was Jim to get away from the swamp. We said there warn’t no home like a raft, after all. Other places do seem so cramped up and smothery, but a raft don’t. You feel mighty free and easy and comfortable on a raft.

Two or three days and nights went by; I reckon I might say they swum by, they slid along so quiet and smooth and lovely. Here is the way we put in the time. It was a monstrous big river down there—sometimes a mile and a half wide; we run nights and laid up and hid daytimes; soon as night was most gone, we stopped navigating and tied up—nearly always in the dead water under a towhead; and then cut young cottonwoods and willows and hid the raft with them. Then we set out the lines. Next we slid into the river and had a swim, so as to freshen up and cool off; then we set down on the sandy bottom where the water was about knee-deep and watched the daylight come. Not a sound anywheres—perfectly still—just like the whole world was asleep, only sometimes the bullfrogs a-cluttering maybe. The first thing to see, looking away over the water, was a kind of dull line—that was the woods on t’other side—you couldn’t make nothing else out; then a pale place in the sky; then more paleness, spreading around; then the river softened up, away off, and warn’t black anymore but gray; you could see little dark spots drifting along, ever so far away—trading scows, and such things; and long black streaks—rafts; sometimes you could hear a sweep screaking, or jumbled-up voices, it was so still, and sounds come so far; and by and by you could see a streak on the water which you know by the look of the streak that there’s a snag there in a swift current which breaks on it and makes that streak look that way; and you see the mist curl up off of the water, and the east reddens up, and the river, and you make out a log cabin in the edge of the woods, away on the bank on t’other side of the river, being a wood yard, likely, and piled by them cheats so you can throw a dog through it anywheres; then the nice breeze springs up and comes fanning you from over there, so cool and fresh and sweet to smell, on account of the woods and the flowers; but sometimes not that way, because they’ve left dead fish laying around, gars and such, and they do get pretty rank; and next you’ve got the full day, and everything smiling in the sun, and the songbirds just going it!

Portraits of Giuliano and Francesco Giamberti da Sangallo, by Piero di Cosimo, 1482–85. Rijksmuseum, on loan from the Koninklijk Kabinet van Schilderijen Mauritshuis.

A little smoke couldn’t be noticed now, so we would take some fish off of the lines and cook up a hot breakfast. And afterward we would watch the lonesomeness of the river and kind of lazy along, and by and by lazy off to sleep. Wake up, by and by, and look to see what done it, and maybe see a steamboat, coughing along upstream, so far off toward the other side, you couldn’t tell nothing about her only whether she was a stern-wheel or side-wheel; then for about an hour there wouldn’t be nothing to hear nor nothing to see—just solid lonesomeness. Next you’d see a raft sliding by, away off yonder, and maybe a galoot on it chopping, because they’re most always doing it on a raft; you’d see the ax flash and come down—you don’t hear nothing; you see that ax go up again, and by the time it’s above the man’s head, then you hear the k’chunk!—it had took all that time to come over the water. So we would put in the day, lazying around, listening to the stillness. Once there was a thick fog, and the rafts and things that went by was beating tin pans so the steamboats wouldn’t run over them. A scow or a raft went by so close we could hear them talking and cussing and laughing—heard them plain; but we couldn’t see no sign of them; it made you feel crawly; it was like spirits carrying on that way in the air. Jim said he believed it was spirits, but I says, “No, spirits wouldn’t say, ‘Dern the dern fog.’ ”

Soon as it was night, out we shoved; when we got her out to about the middle, we let her alone, and let her float wherever the current wanted her to; then we lit the pipes and dangled our legs in the water and talked about all kinds of things—we was always naked, day and night, whenever the mosquitoes would let us—the new clothes Buck’s folks made for me was too good to be comfortable, and besides, I didn’t go much on clothes, nohow.

Sometimes we’d have that whole river all to ourselves for the longest time. Yonder was the banks and the islands, across the water; and maybe a spark—which was a candle in a cabin window—and sometimes on the water you could see a spark or two—on a raft or a scow, you know; and maybe you could hear a fiddle or a song coming over from one of them crafts. It’s lovely to live on a raft. We had the sky, up there, all speckled with stars, and we used to lay on our backs and look up at them and discuss about whether they was made or only just happened—Jim he allowed they was made, but I allowed they happened; I judged it would have took too long to make so many. Jim said the moon could a laid them; well, that looked kind of reasonable, so I didn’t say nothing against it, because I’ve seen a frog lay most as many, so of course it could be done. We used to watch the stars that fell, too, and see them streak down. Jim allowed they’d got spoiled and was hove out of the nest.

Once or twice of a night, we would see a steamboat slipping along in the dark, and now and then she would belch a whole world of sparks up out of her chimbleys, and they would rain down in the river and look awful pretty; then she would turn a corner, and her lights would wink out and her powwow shut off and leave the river still again; and by and by her waves would get to us, a long time after she was gone, and joggle the raft a bit, and after that you wouldn’t hear nothing for you couldn’t tell how long, except maybe frogs or something.

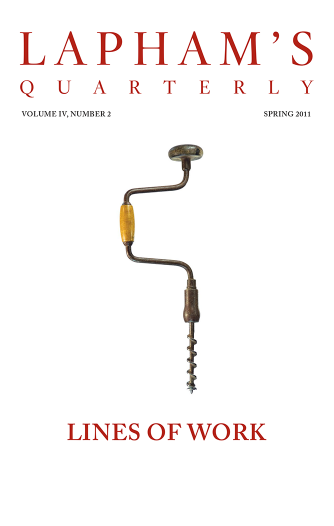

From The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Shortly after its publication, the book was banned by the Concord Free Public Library in Massachusetts, with one committee member calling it “trash of the veriest sort.” Within days, news of the ban had spread across the country. “If Mr. Clemens cannot think of something better to tell our pure-minded lads and lasses,” said Louisa May Alcott, “he had best stop writing for them.” The book sold 51,000 copies within three months. Twain remarked that it was a “generous action” of the library to “have condemned and excommunicated my last book and doubled its sale.”

Back to Issue