It’s good to remember that in crises, natural crises, human beings forget for a while their ignorances, their biases, their prejudices. For a little while, neighbors help neighbors and strangers help strangers.

—Maya Angelou, 2011Them

When we talk about the foreign, the question becomes one of us versus them. But in the end, is one just the opposite side of the other?

By Lewis H. Lapham

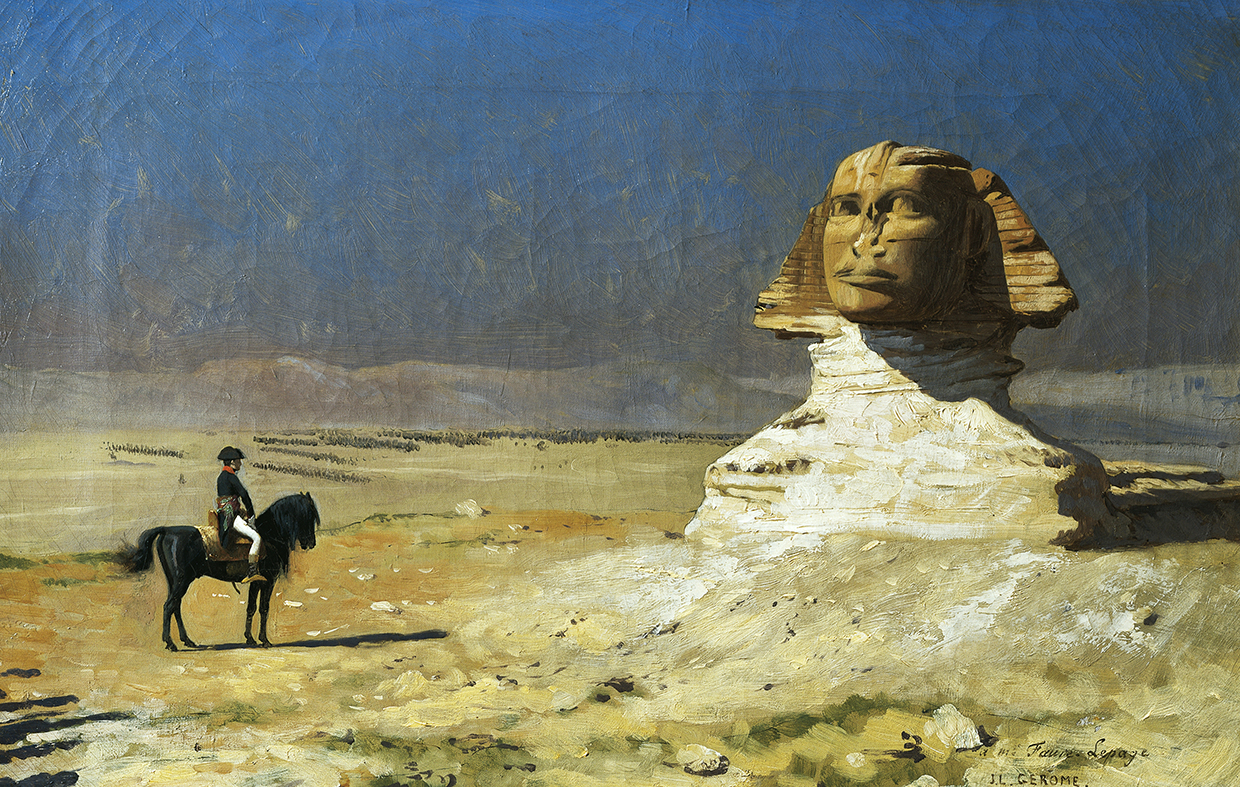

Napoleon and his General Staff in Egypt, by Jean-Léon Gérôme, 1867.

All good people agree,

And all good people say,

All nice people, like Us, are We

And everyone else is They:

But if you cross over the sea,

Instead of over the way,

You may end by (think of it!) looking on We

As only a sort of They!—Rudyard Kipling

To listen to the president of the United States explain why and with whom America is currently at war in the Arab Middle East is to be reminded of Sam Goldwyn intent on making a movie of Lillian Hellman’s play The Children’s Hour. Informed by a studio executive that the women in the play were lesbians, their presence on screen certain to be forbidden by the film industry’s censors, the producer of epic Hollywood struggles with the question of good and evil said, “So what’s the problem? Make them Albanians.”

The story may be apocryphal, but then so is much of the intel revising the president’s weekly lineups of the damned and the saved—Iran one day an enemy, the next day an ally; the Saudis consulting prayer books maleficent and benign; some Arabs to be seen as human beings, others as monsters, it never being clear which is which. To avoid mistakes the American command and control center in Florida calls down air strikes on Islamists of every known variety (Sunni and Shiite, Taliban, Alawite and Al Qaeda) in Syria, Pakistan, Libya, Iraq, Yemen, Somalia, and Afghanistan—i.e., on targets distinguished primarily by their not being Us, and therefore (think of it!) an all-inclusive, equal opportunity Them.

The policy accords with various doctrines of American exceptionalism and with the anthropological truth told by Simone de Beauvoir: “No group ever sets itself up as the One without at once setting up the Other over against itself. If three travelers chance to occupy the same compartment, that is enough to make vaguely hostile ‘Others’ out of all the rest of the passengers on the train.” Off the train or on the plantation, any grouping of human race, creed, color, nationality, bloodline, net worth, zip code, or hat size serves to distinguish a We from a They. Sigmund Freud ascribes the separations of the wheat from the chaff to the “narcissism of minor differences” that makes of mankind’s aggressive and inborn hostility toward strangers an asset “not to be despised.” Further strengthenings of the self-centered instinct for survival recruit even greater numbers of people into some sort of ring of fellowship (church or gender, red state or blue) by populating the terra incognita outside the ring with enough barbarians to verify the existence of a civilization within—to define the preferred stock by what, as all good people agree, it decidedly is not.

General Bonaparte in Egypt, by Jean-Léon Gérôme, 1867. © De Agostini Picture Library, G. Dagli Orti, Bridgeman Images.

The instinct is long-abiding, awarded a high value in the Hebrew Bible, the Homeric poems, and the Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh. The Histories composed by Herodotus in the fifth century bc partitions the land of the living into an East and a West, and like the makers of myths and tabloid headlines, historians ever since have tended to favor views of a world divided between the forces of light and the powers of darkness, the flags always there on the battlements and no mixing of motives or blood. To sustain the dramatic narrative of ongoing hostilities (and with it the illusion of a chosen few, a heavenly host, a band of brothers) they bundle minor individual differences into major collective identities—Persian and Greek, Roman and Pagan, Christian and Muslim, Protestant and Catholic, Cowboy and Indian, Proletariat and Bourgeoisie.

War makes a better story than peace, and so the Roman historian Livy finds the Carthaginian general Hannibal at the head of an invading army of African infantry and elephants in the north of Italy in 218 bc saying to his troops that they are stronger and better men than their corrupted Roman adversaries, charging them to draw their swords “with God’s blessing” because their only choice is “to conquer or die.” From the perspective of those being trespassed against, the voice is that of the Shawnee chief

Tecumseh drumming up intertribal Indian resistance to the white men infiltrating the Ohio River Valley around 1811: “Brothers—The white men want more than our hunting grounds; they wish to kill our warriors; they would even kill our old men, women, and little ones.”

The chroniclers stage the battles fought by Tecumseh and Hannibal as combat between collective identities, which on closer acquaintance turn out to be of little help with learning where and how the past lives in the present. The German poet Friedrich Schiller remarked on the rhetorical sleight of hand, “The concrete life of the individual is destroyed in order that the abstract idea of the whole may drag out its sorry existence.”

The encounters with the foreign noted in this issue of Lapham’s Quarterly take place for the most part between individuals, and are therefore more likely to lead to the well-being of both the One and the Other than to the hostilities, no matter how sacred or just, that are joint ventures in ruin and loss. The emphasis accounts for the fact that the history of mankind is not one story but many stories, the collected works of all the individuals ever to know the light of day and the dread of night, each composed of multiple identities—physical and metaphysical, public and private—often as foreign to one another as white is to black. The goings along to get along, the everyday traffic among people met on a road, in a market or a tavern or a park, make up the far greater part of the unwritten record than do the descents into the maelstroms of violence.

In a nineteenth-century New England seaport the teller of the tale that is Herman Melville’s Moby Dick finds himself quartered in the Spouter Inn with a heathen harpooner “of a dark, purplish, yellow color,” intricately checkered with green and black tattoos, holding in one hand a tomahawk, in the other a shrunken head. A fearful sight, but when at the innkeeper’s direction it comes to sharing the same bed, Ishmael thinks to himself, “the man’s a human being just as I am: he has just as much reason to fear me, as I have to be afraid of him. Better sleep with a sober cannibal than a drunken Christian.”

The thought lies at the heart of the American democratic idea, implicit in the writings of Thomas Paine and Thomas Jefferson, explicit in

J. Hector St. John de Crèvecoeur’s Letters from an American Farmer asking in 1782, “What then is the American, this new man? He is either a European, or the descendant of a European, hence that strange mixture of blood, which you will find in no other country. I could point out to you a family whose grandfather was an Englishman, whose wife was Dutch, whose son married a Frenchwoman, and whose present four sons have now four wives of different nations.”

What joins the Americans one to another is not a common ancestry, language or race, but a shared work of the imagination that looks forward to the making of a future, not backward to the insignia of the past. Their enterprise is underwritten by a Constitution that allows for the widest horizons of sight and the broadest range of expression, supports the liberties of the people as opposed to the ambitions of the state, and stands as premise for a narrative rather than plan for an invasion or a monument. The narrative was always plural; not one story, many stories, all of them given the chance of making sense or love or money. Love of country follows from the exercise of its freedoms, not from pride in its fleets or its armies.

John Quincy Adams made the point in a Fourth of July speech in 1821, as the then secretary of state declining to send the U.S. Navy to liberate the colonies of Venezuela and Colombia from the imperialist grasp of Catholic Spain. The glorious intention was popular at the time among politicians in Washington, many of them proud owners of Negro slaves, eager to steer for what they pre-positioned as victories both easy and safe.

America, Adams said, “goes not abroad in search of monsters to destroy.” If she were to enlist “under other banners than her own, were they even the banners of foreign independence, she would involve herself beyond the power of extrication, in all the wars of interest and intrigue, of individual avarice, envy and ambition, which assume the colors, and usurp the standard of freedom. The fundamental maxims of her policy would insensibly change from liberty to force...She might become the dictatress of the world: she would be no longer the ruler of her own spirit.”

Adams was reminding the gentlemen in high silk hats that within the American scheme of things the policies of liberty and force have been at each other’s throats ever since the Puritan forefathers landing in Massachusetts Bay in the 1620s fell first on their knees, then on the aborigines. The immigrants on the near shore of the seventeenth-century Atlantic Ocean were of as mixed a company as Crèvecoeur’s acquaintances in eighteenth-century New York, all of them foreign but most of them Christian. Along with the advantage of gunpowder, they were armed with the mandate of heaven set forth in Deuteronomy: “When the Lord your God brings you into the land that you are about to enter and occupy” he gives over to you the peoples who happen to be already present, and “then you must utterly destroy them...the Lord your God has chosen you out of all the peoples on earth to be his people, his treasured possession.”

The hard-line Old Testament thinking accounts for much of the unfolding of America’s history over the last four hundred years—the extensive holding of slaves north and south of the Potomac, the wholesale slaughter of Indian tribes east and west of the Mississippi, the hostilities neither minor nor vague that seeded the killing fields of the Civil War, the humiliation and detention of late-arriving immigrants in the slums of collective identity (dago, polack, yid, chink, frog), broken on the wheels of the industrial revolution.

The Indian and Mexican trouble in the west went the way of all flesh, to be replaced in the 1880s by labor trouble in the nation’s eastern coal mines and steel mills. Severe economic misery in 1884, again in 1893 and 1896, drove the herds of unemployed poor into the corrals of ungovernable despair. War and the rumors of war between the rich and the poor prompted all the nice propertied people like us (on the sunny side of Fifth Avenue, in the leafy suburbs of Boston and Philadelphia) to agree that the time had come to outsource the fear and loathing of foreigners, to send it back across the sea to where it belonged, and to go abroad in search of monsters to escape from having to deal with the troubles at home.

Rudyard Kipling posted the message in McClure’s magazine in February 1899 under the title “The White Man’s Burden: The United States and the Philippine Islands”:

Send forth the best ye breed—

Go bind your sons to exile

To serve your captives’ need;

To wait in heavy harness,

On fluttered folk and wild—

Your new-caught, sullen peoples,

Half-devil and half-child.

The Philippines had been recently acquired as spoil of the Spanish-American War; so had Col. Theodore Roosevelt’s flag- and sword-waving magnificence as the champion of American overseas empire. In Cuba with his cavalcade of Rough Riders, he had become the hero of San Juan Hill; upon becoming president of the United States in 1901 subsequent to the assassination of President William McKinley (by an anarchist in Buffalo), Roosevelt made no secret of his Christian belief that America was destined to manage the affairs of a troublesome and misguided world.

Neither did President Woodrow Wilson when, in 1917, he enlisted America in

World War I to establish its bona fides as the world’s newborn colossus (military, economic, and moral) rising from the rubble of the old European empires (British, German, Ottoman, Russian, Austro-Hungarian, and French) that had engineered their several extinctions in a fury of blind abstractions that destroyed the lives of 37.5 million combatants in order to drag out the sorry existence of eagles on a flag. America’s late and decisive entry into the war clothed Wilson in the robes of a saint, going abroad to restore peace on earth and good will toward men, committing the United States to shoulder the white man’s burden everywhere in a new, post-1918 world order to be jointly administered by the maxims of liberty and force.

As maxims the two words look well together in luxury automobile commercials, but as policies they don’t make good bedfellows, even though they seemed to do so during the brief, shining moment of the Second World War. Japan and Germany had visited hostilities upon the United States, and as a boy in San Francisco age six to ten in the years from 1941 to 1945, I was proud to learn that might was right, America the embodiment of both, the aircraft carriers in the bay armed with the Old Testament wrath of God and the New Testament parable of the Good Samaritan.

Reception of a Venetian Delegation in Damascus in 1511 (detail). Venetian school, c. 1525. Louvre, Paris, France.

It was never a problem to distinguish Us from Them. Posters appeared in toy store windows pointing to the difference in the slant of the eyes on the face of a Jap and the face of a Chinaman, the one to be regarded as an insect or rodent, the other as the genial proprietor of the store. In the newsreels and the pages of Life and the Saturday Evening Post, the Nazis appeared as avatars of Attila the Hun; my governess was German, and on her shortwave radio in the kitchen it was easy to recognize in the voice of Adolf Hitler the barbarous squawking of an outraged parrot.

It was five years before I heard the same sound in the voice of Sen. Joseph R. McCarthy seeking to exterminate communist rodents and insects infesting the State Department and Hollywood’s film studios, another fifteen years before President Lyndon B. Johnson sent forth America’s sons to wait in heavy harness on the fluttered folk and wild in the forests of Vietnam. The Cold War with the Russians meanwhile was requiring the teardown of a democratic republic to clear the ground for the McMansion of military world empire.

My own encounters with the foreign during those same twenty years were taking place in the terra incognita that was everywhere in America beyond the San Francisco neighborhood of Pacific Heights, then as now an enclave reserved for the city’s high-end society—uniformly white, for the most part Protestant, decorously liberal in its politics, devout in its worship of money. At the age of thirteen I had never seen snow before my parents moved to New York City in 1948; neither had I come across many Negroes (the word still in use) who were not in domestic or military service; the discriminating against Jews I took to be a pathology for the most part prevalent in Europe, horrific in its consequences in Nazi Germany but also notorious in Russia and France.

The French poet Charles Baudelaire suggests that the learning of the ways of the world is best done by “taking a bath of multitude” with “a craving for disguises and masks” that allows for the being oneself and an other. A difficult trick of which he knew “not everyone is capable,” but one that I attempted in the 1960s as a newspaper reporter working a police beat in California or covering the United Nations in New York during the visitations of Nikita Khrushchev and Fidel Castro. Later in the decade I served as a correspondent for national magazines on investigative errands to Wall Street, Hollywood, and Alaska, for a season with the White House press corps in Washington, to a making of rounds in the country’s law courts and military installations.

I never managed to achieve Baudelaire’s “holy prostitution of the soul which gives itself totally...to the unexpected which appears, to the unknown which passes by,” but I was shown the reason for my failure in a dream that for fifty years I’ve been careful to remember. One of the masks and disguises that I was trying on in the 1960s was that of the renegade artist under the instruction of Gustave Flaubert’s 1867 letter to George Sand, “Axiom: Hatred of the bourgeois is the beginning of virtue”; my reading of nineteenth-century French novelists I supplemented by spending a good deal of time in the old Birdland on Broadway at West Fifty-second Street in the company of the music of Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Charlie Parker, Thelonious Monk, and Charles Mingus.

In the dream Mingus is wearing his porkpie hat, I’m in a Brooks Brothers sweater, and we’re sitting together on the red leatherette in the semicircular booth just next to the bandstand. He proposes an uptempo riff on the theme of desegregation; suggesting that we exchange address books, and by so doing, trade identities. (I never owned an address book; I don’t know whether Mingus did, but in the dream they are identical, bound in snakeskin, our names on the covers embossed in gold.) Mingus pushes his book into the center of the table; so do I, but then, at the last second, I snatch it back. Mingus looks at me for what seems like a long time with sorrowful amusement. Then he laughs and says, “You don’t really mean to tell me that you’re having that much fun with yours.”

I wasn’t, but neither did I have Baudelaire’s courage to face down the fear of the unknown, which in that instant I was ashamed to discover was not the key signature change from white to black but the mortal fear of being poor—the indelible mark bred in the bones of the American bourgeois, and one of my several disguises that I could deplore but not shed. It wasn’t that I was superbly rich or expecting to become so, but growing up with a comfortable view of the Golden Gate Bridge I’d been settled in the opinion that to travel safely in the world one must go as money’s guest. I didn’t know how to leave home without it.

The thought is not one I like to have or to hold, but it accounts for the fact that America is no longer the ruler of her own democratic spirit, which is never far from anarchy. Its true character is that of the chronic revolutionary and lifelong pilgrim, adrift at birth in an existential void, inheriting not much of anything except the hope of improvising the scheme of a plausible identity with which to light out for the territories, perhaps to float south to an island in the sun.

During the second half of the century headlined in the history books as America’s own, I met with less and less of that spirit among the country’s ruling and possessing classes—in Manhattan and Beverly Hills as also in the Washington news media and the Ivy League schools—and I could see more and more plainly that although America had become dictatress of the world, she was a very frightened dictatress, afraid of foreigners, scared of her own shadow. For the last seventy years the governments in Washington have been diligent in the acquisition of distant monsters—“sullen peoples, half-devil and half-child” in communist Russia and communist China, in Korea, Vietnam, Nicaragua, Congo, Cuba, Guatemala, Indonesia, Iran, Panama, Afghanistan, Iraq—with which to terrify all the good and nice people at home and persuade them to give up the democratic spirit of liberty in return for the protection of force.

The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 left the architects of American Empire temporarily at a loss for enemies of sufficient number and nuclear throw-weight to justify the high levels of military spending that secured the health of the American economy. The destruction of the World Trade Center on September 11, 2001, removed the impediment. President George W. Bush raked from the ashes a holy crusade against all “the evil-doers that hate America,” saying to a joint session of Congress that “every nation in every region now has a decision to make: either you are with us, or you are with the terrorists.”

I am a man: I consider nothing human alien to me.

—Terence, 163 BCThe statement raised the question as to who properly belongs within the ring of fellowship defined as the American Us. By way of a hedge against a possible downturn in the foreign market for monsters, the proponents of the Pax Americana had been careful ever since the end of World War II to develop an emergent domestic market. Begin the narrative almost anywhere in the 1950s and for the next half century the practice of democracy comes to be seen by the authorities as both uncivil and unsafe. Too much freedom wandering around loose in the streets and too many people having thoughts of their own undermine the ambitions of the state; long before the evil date of 9/11, the rapidly metastasizing national security agencies were separating the homegrown damned from the homegrown saved. The recent and even more rapid technological upgrades attest to the pathology of a government so afraid of its own citizens that it classifies them as probable enemies.

Hydra-headed databanks target schoolchildren and the mothers of schoolchildren, church congregations, credit card members, and Facebook friends, anybody at work or at play with a tracking device sold under the label of an iPhone. An NSA device code-named COTTONMOUTH-I can remotely monitor anybody’s computer; the CANDYGRAM asset is capable of setting up a telephone tripwire to mimic a cell phone tower. Tens of thousands of surveillance cameras conduct “truth maintenance” and “event prediction.” If all goes well, what comes up on the screens is an American democracy as safely dead as a pheasant under glass.

Democracy is a middle-class enterprise, and the ever-widening spread of income inequality over the last thirty years has reduced the American middle-class to the ever-larger and unknown horde seen by presidential candidate Mitt Romney as the 47 percent of Americans who don’t take responsibility for themselves, by Republican congressman Paul Ryan as “takers.” The 5 percent of the population in the upper reaches of net worth regard themselves as peers in the realm of a global plutocracy, having less in common with their once-upon-a-time fellow citizens of the United States than they do with their counterparties in Zurich, Bahrain, and Mumbai.

The geopolitics of money transcend the boundaries and integrity of sovereign states, and the world divides on the one axis between the citadels of the rich and the wastelands of the poor. Beverly Hills and the Upper East Side of Manhattan belong to the same polity as the sixteenth arrondissement in Paris or the Peak in Hong Kong; the yachts moored off Cannes and the Costa Brava sail under the flag of the same admiralty that posts squadrons in Bali and Miami Beach.

The American hedge fund princess or prince avoids fraternizing with the local rustics who don’t travel by private plane, can’t afford a private security detail, private school, or personal trainer. The downmarket American becomes as foreign and frightful as a wandering Arab or an African disease—thus providing the command and control centers of American power with monsters both at home and abroad, and therefore (think of it!) with an all-inclusive, equal opportunity Them.