People react to fear, not love—they don’t teach that in Sunday school, but it’s true.

—Richard Nixon, 1975Night Vision

The Sandman is coming.

Except at dinnertime, my brothers and sisters and I used to see my father very little during the day.

He was, perhaps, busily engaged at his ordinary profession. After supper, which was served according to the old custom at seven o’clock, we all went with my mother into my father’s study and seated ourselves at the round table, where he would smoke and drink his large glass of beer. Often he told us wonderful stories and grew so warm over them that his pipe continually went out. Whereupon I had to light it again with burning paper, which I thought great sport. Often, too, he would give us picture books and sit in his armchair, silent and thoughtful, puffing out such thick clouds of smoke that we all seemed to be swimming in the clouds. On such evenings as these, my mother was very melancholy, and immediately as the clock struck nine she would say, “Now, children, to bed—to bed! The Sandman’s coming, I can see.” And indeed, on each occasion I used to hear something with a heavy, slow step come thudding up the stairs. That I thought must be the Sandman.

Once, when the dull noise of footsteps was particularly terrifying, I asked my mother as she bore us away, “Mama, who is this naughty Sandman, who always drives us away from Papa? What does he look like?”

“There is no Sandman, dear child,” replied my mother. “When I say the Sandman’s coming, I only mean that you’re sleepy and can’t keep your eyes open—just as if sand had been sprinkled into them.”

This answer of my mother’s did not satisfy me—nay, the thought soon ripened in my childish mind that she only denied the Sandman’s existence to prevent our being terrified of him. Certainly, I always heard him coming up the stairs. Most curious to know more of this Sandman and his particular connection with children, I at last asked the old woman who looked after my youngest sister what sort of man he was.

“Eh, Natty,” said she, “don’t you know that yet? He is a wicked man, who comes to children when they won’t go to bed, and throws a handful of sand into their eyes, so that they start out bleeding from their heads. He puts their eyes in a bag and carries them to the crescent moon to feed his own children, who sit in the nest up there. They have crooked beaks like owls so that they can pick up the eyes of naughty human children.”

A most frightful picture of the cruel Sandman was horribly depicted in my mind, so that when I heard the noise on the stairs, I trembled with agony and alarm, and my mother could get nothing out of me but the cry of “The Sandman, the Sandman!” stuttering forth through my tears. I then ran into the bedroom, where the frightful apparition of the Sandman terrified me during the whole night.

I had already grown old enough to realize that the nurse’s tale about him and the nest of children in the crescent moon could not be quite true, but nevertheless this Sandman remained a fearful specter, and I was seized with the utmost horror when I heard him once not only come up the stairs but violently force my father’s door open and go in. Sometimes he stayed away for a long period, but more often his visits came in close succession. This lasted for years, but I could not accustom myself to the terrible goblin; the image of the dreadful Sandman did not become any fainter. His intercourse with my father began more and more to occupy my fancy. Yet an unconquerable fear prevented me from asking my father about it. But if I, I myself, could penetrate the mystery and behold the wondrous Sandman—that was the wish which grew on me with the years. The Sandman had introduced me to thoughts of the marvels and wonders that so readily gain a hold on a child’s mind. I enjoyed nothing better than reading or hearing horrible stories of goblins, witches, pygmies, etc., but most horrible of all was the Sandman, whom I was always drawing, in the oddest and most frightful shapes, with chalk or charcoal on the tables, cupboards, and walls.

When I was ten years old, my mother removed me from the night nursery into a little chamber situated in a corridor near my father’s room. Still, as before, we were obliged to make a speedy departure on the stroke of nine, as soon as the unknown step sounded on the stair. From my little chamber I could hear how he entered my father’s room, and it was then that I seemed to detect a thin vapor with a singular odor spreading through the house. Stronger and stronger, with my curiosity, grew my resolution somehow to make the Sandman’s acquaintance. Often I sneaked from my room to the corridor when my mother had passed, but never could I discover anything, for the Sandman had always gone in at the door when I reached the place where I might have seen him. At last, driven by an irresistible impulse, I resolved to hide myself in my father’s room and await his appearance there.

From my father’s silence and my mother’s melancholy, I perceived one evening that the Sandman was coming. I therefore feigned great weariness, left the room before nine o’clock, and hid myself in a corner close to the door. The housedoor groaned and the heavy, slow, creaking step came up the passage and toward the stairs. My mother passed me with the rest of the children. Softly, very softly, I opened the door of my father’s room. He was sitting, as usual, stiff and silent, with his back to the door. He did not perceive me, and I swiftly darted into the room and behind the curtain that covered an open cupboard close to the door in which my father’s clothes were hanging. The steps sounded nearer and nearer—there was a strange coughing and scraping and murmuring without. My heart trembled with anxious expectation. A sharp step close, very close, to the door—the quick snap of the latch, and the door opened with a rattling noise. Screwing up my courage to the utmost, I cautiously peeped out. The Sandman was standing before my father in the middle of the room, the light of the candles shone full upon his face. The Sandman, the fearful Sandman, was the old advocate Coppelius, who had often dined with us.

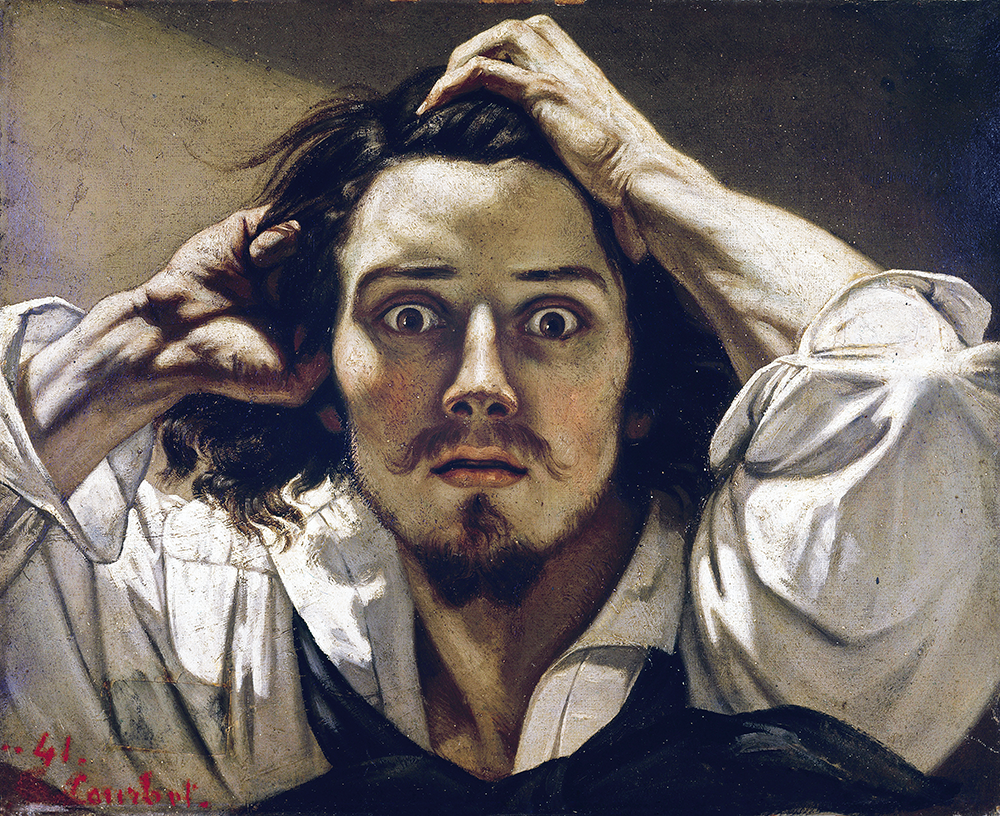

The Desperate Man, self-portrait by Gustave Courbet, 1843–45. © Luisa Ricciarini / Leemage / Bridgeman Images.

But the most hideous form could not have inspired me with deeper horror than this very Coppelius. Imagine a large, broad-shouldered man, with a head disproportionately big, a face the color of yellow ocher, a pair of bushy gray eyebrows, from beneath which a pair of green cat’s eyes sparkled with the most penetrating luster, and with a large nose curved over his upper lip. His wry mouth was often twisted into a malicious laugh, when a couple of dark red spots appeared on his cheeks, and a strange hissing sound was heard through his gritted teeth. Coppelius always appeared in an ashen-gray coat, cut in old-fashioned style, with waistcoat and breeches of the same color, while his stockings were black, and his shoes adorned with agate buckles.

His little peruke scarcely reached farther than the crown of his head, his curls stood high above his large red ears, and a broad hair-bag projected stiffly from his neck, so that the silver clasp which fastened his folded cravat might be plainly seen. His whole figure was hideous and repulsive, but most disgusting to us children were his coarse brown hairy fists. Indeed, we did not like to eat anything he had touched with them. This he had noticed, and it was his delight, under some pretext or other, to touch a piece of cake or some nice fruit, that our kind mother might quietly have put on our plates, just for the pleasure of seeing us turn away with tears in our eyes, in disgust and abhorrence, no longer able to enjoy the treat intended for us. He acted in the same manner on holidays, when my father gave us a little glass of sweet wine. Then would he swiftly put his hand over it, or perhaps even raise the glass to his blue lips, laughing most devilishly, and we could only express our indignation by silent sobs. He always called us “the little beasts”; we dared not utter a sound when he was present, and we heartily cursed the ugly, unkind man who deliberately marred our slightest pleasures. My mother seemed to hate the repulsive Coppelius as much as we did, since as soon as he showed himself, her liveliness, her open and cheerful nature, was changed for a gloomy solemnity. My father behaved toward him as though he were a superior being, whose bad manners were to be tolerated and who was to be kept in good humor at any cost. He need only give the slightest hint, and favorite dishes were cooked, the choicest wines served.

When I now saw this Coppelius, the frightful and terrific thought took possession of my soul that indeed no one but he could be the Sandman. But the Sandman was no longer the bogey of a nurse’s tale, who provided the owl’s nest in the crescent moon with children’s eyes. No, he was a hideous, spectral monster, who brought with him grief, misery, and destruction—temporal and eternal—wherever he appeared.

Fear is a poor guarantor of a long life.

—Marcus Tullius Cicero, 44I was riveted to the spot, as if enchanted. At the risk of being discovered and, as I plainly foresaw, of being severely punished, I remained with my head peeping through the curtain. My father received Coppelius with solemnity.

“Now to our work!” cried the latter in a harsh, grating voice as he flung off his coat.

My father silently and gloomily drew off his dressing gown, and both attired themselves in long black frocks. Whence they took these I did not see. My father opened the door of what I had always thought to be a cupboard. But I now saw that it was no cupboard, but rather a black cavity in which there was a little fireplace. Coppelius went to it, and a blue flame began to crackle up on the hearth. All sorts of strange utensils lay around. Heavens! As my old father stooped down to the fire, he looked quite another man. Some convulsive pain seemed to have distorted his mild features into a repulsive, diabolical countenance. He looked like Coppelius, whom I saw brandishing red-hot tongs, which he used to take glowing masses out of the thick smoke, objects he afterward hammered. I seemed to catch a glimpse of human faces lying around without any eyes, but with deep holes instead.

“Eyes here, eyes!” roared Coppelius tonelessly. Overcome by the wildest terror, I shrieked out and fell from my hiding place upon the floor. Coppelius seized me and, baring his teeth, bleated out, “Ah—little wretch—little wretch!” Then he dragged me up and flung me on the hearth, where the fire began to singe my hair. “Now we have eyes enough—a pretty pair of child’s eyes,” he whispered, and taking some red-hot grains out of the flames with his bare hands, he was about to sprinkle them in my eyes.

Upon this my father raised his hands in supplication, crying, “Master, master, leave my Nathaniel his eyes!”

Whereupon Coppelius answered with a shrill laugh, “Well, let the lad have his eyes and do his share of the world’s crying, but we will examine the mechanism of his hands and feet.”

And then he seized me so roughly that my joints cracked, and screwed off my hands and feet, afterward putting them back again, one after the other. “There’s something wrong here,” he mumbled. “But now it’s as good as ever. The old man has caught the idea!” hissed and lisped Coppelius. But all around me became black, a sudden cramp darted through my bones and nerves, and I lost consciousness. A gentle, warm breath passed over my face; I woke as from the sleep of death. My mother had been stooping over me.

“Is the Sandman still there?” I stammered.

“No, no, my dear child, he has gone away long ago—he won’t hurt you!” said my mother, kissing her darling as he regained his senses.

E.T.A. Hoffmann

From “The Sandman.” First published in the Prussian writer’s 1817 book The Night Pieces, this tale plays on a mythical figure folklorists trace back to Morpheus, the Greek god of dreams. Sigmund Freud called Hoffmann “the unrivaled master of conjuring up the uncanny” in his 1919 essay on the subject, arguing there was a “substitutive relation between the eye and the male member”—that the threat of castration makes the fear of losing an eye “peculiarly violent.”