It costs a lot to make a person look this cheap.

—Dolly Parton, 1994Shop Talk

Fighting for American-made fashion.

Our shop, called Hawes-Harden, was on the fourth floor of 8 West Fifty-sixth Street. Some small dressmaker had just failed on the spot and we inherited a gray rug, light beige walls, four fitting rooms, and a few workroom tables. Into the showroom came some furniture from the Hardens’ attic, a fine carved cabinet with many little drawers for samples, some English tables and chairs, a large red velvet couch. The room was about twenty-five by thirty-five feet, the street side all windows.

The first fitting room was made into a model room. Clothes must be made and shown on live people, I had learned. We started with two very young girl models. One of them, a Cooper Union graduate, stayed for three years with me. She not only modeled but ran the entire stockroom, did all the ordering of materials, and all the sketching. Quite a girl, that. Now she designs children’s clothes for a wholesale house.

The back end of the floor was a workroom, about the size of the showroom with a space cut off for a stockroom. Here we subsequently lost money.

Gaily we started out. We made the rounds of the French fabric houses, all of whom maintain New York offices. It did not occur to me that anyone made material in the United States. We ordered what we liked for our first collection. Our credit was guaranteed by Mr. Harden. Little did I appreciate the boon. Only later was I brought to any realization of just what it meant.

Our fitter was a dressmaker from Rutherford, a Romanian woman, big and strong and blond. She received, I think, about seventy-five dollars a week. The drapers and finishers were hired by putting ads in the paper. All made-to-order workrooms are set up in the same manner. The chief is the fitter who is responsible for the entire staff of her room and what they produce. Under her are drapers, girls who cut the orders from the muslin patterns that are made for the original design. These drapers cut and prepare the work for finishers who sew up the clothes. Each draper has from four to eight finishers depending on her ability to keep them busy.

Rosemary and I each made models, working with the fitter. We had about forty things in the first collection, which we showed on December 16, 1928. I remember the date well because that is my birthday. It was my twenty-fifth. I had made a sort of bet with myself, while fiddling about in Paris, that by my twenty-fifth birthday I’d get serious.

I later learned that nobody ever opens a shop of that type except in the early fall. Expensive clothes sell much better in the fall since the women are going to be in town and must have their best clothes for being social. In the spring everyone is thinking about going to the country. People use a lot of inexpensive sport clothes. We do nearly two-thirds of our yearly Hawes business in the fall.

Anyway, I didn’t know much of anything in 1928 except that I wanted to design clothes and I was doing it. We had a cocktail party for friends and the press. My time in France had taught me the value of the press. I had not yet, however, learned about American press agents. We were our own press agents.

Frank Crowninshield announced at our opening. He was a friend of Mr. Harden’s. With him came Vogue. Harper’s Bazaar was there because I knew someone on it. Other women’s magazines were there for the same reason. Alice Hughes was brought by someone. Everyone was pleasant and gave us a boost.

We were off. Rosemary and I did all the selling. We had an outside bookkeeper who came in once a week, checked the bills, and kept up the books. I ran the checkbook. The two models did everything else except sweep the floor. That was done by the elevator man. We were a closely knit and not too inefficient organization on the whole.

The fitter did her best to fit as I wanted her to. I think every young designer in America starts with the same problem. Years later, when you are paying out hundreds of dollars for the best fitter you can hire at any price, you hear tales about how your clothes don’t fit.

My early fitters come particularly to mind because certainly Hawes-Harden was set up with definite principles. The first was that we would design everything we sold and that it would be made-to-order of good material, well sewn, and well fitted.

We had our troubles with those principles, since, for one thing, excellent fitters are hard to get and cost a great deal of money, how much I did not realize in the beginning. The best fitters get a good hundred dollars a week all the year around and are well worth it.

After you have your good fitter, she has to train a complete workroom as the standards of workmanship in New York are anything but high. It took, I should say, a full four years to be able to live up to my first principles concerning workmanship.

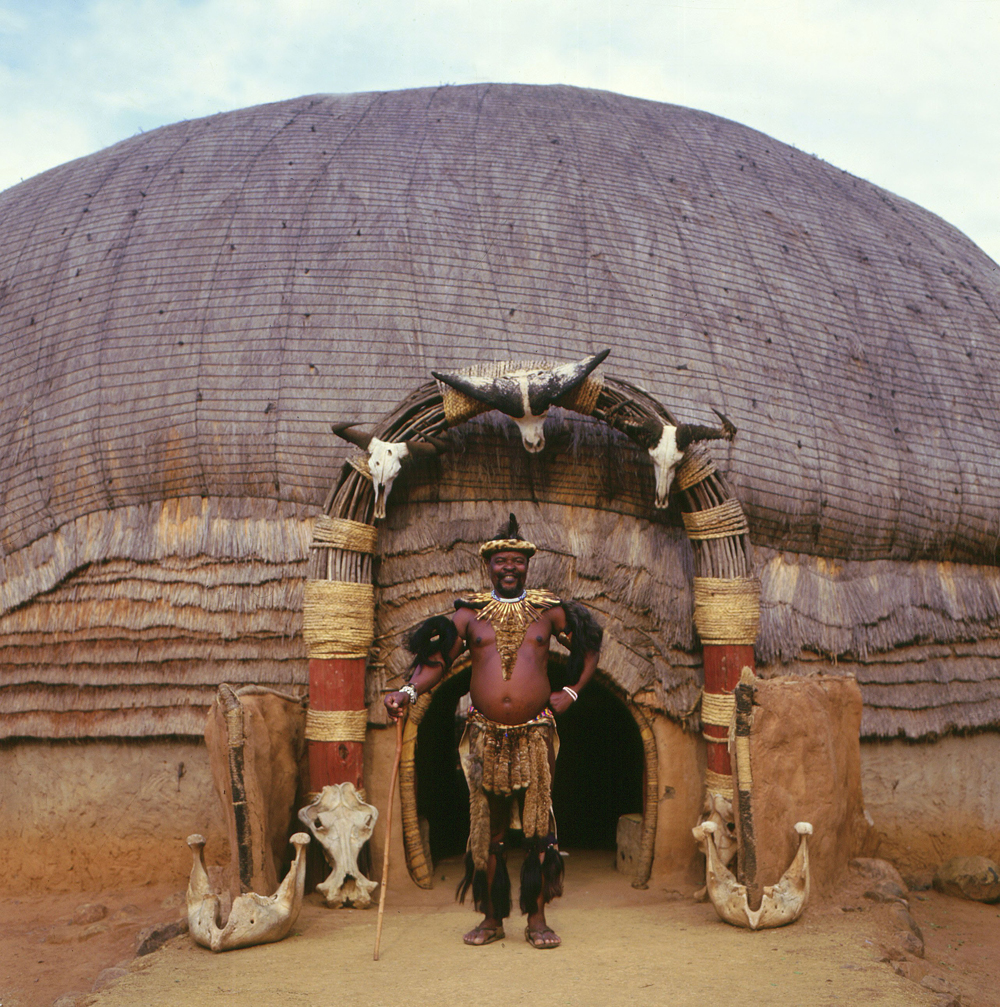

Zulu man standing outside his beehive hut, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Photograph by Stephanie Colasanti. © Stephanie Colasanti / The Art Archive at Art Resource, NY.

What I hoped to do in the shop, in selling my designs, was equally clear to me from the beginning. I wanted to thoroughly satisfy the desires of any number of people who turned out to like my way of designing. I did not intend to try and please a fashionable clientele who labored under the delusion that all clothes were designed in France.

We were definitely not in a position to furnish all the service that expensive specially shops like Bergdorf and Carnegie gave. We were limited in space, lodged on a crowded street. We did not have enough salespeople to go around. We committed every sin of omission possible in the beginning.

We often found it advisable to send the proper flowers with evening clothes to placate the irate customer for being an hour late to dinner in her new Hawes-Harden dress. We kept people waiting hours for fittings, sometimes days.

There was one and only one boast that Hawes-Harden could rightfully make. Nothing that was bought from us could be bought anywhere else at any price. It was not always quite as well-made and fitted as some of our competitors in made-to-order clothes, but it was really exclusive.

This, as I had suspected, proved a sufficient inducement to a public wearied and sickened by copies of French models. They came in to look, often remained to buy.

When I showed my first collection in New York in 1928, the general opinion was that, if by any chance I could successfully design clothes without going to France to copy, it was just a fluke. At first I argued, but eventually I was too busy making clothes to talk about it.

Perhaps I deserved a reputation for eccentricity. I think not, but I laid the ground for it with my own hand. In the first collection in 1928 I showed a dress with a very long name. It was called “1929, perhaps—1930, surely.” It was reminiscent of a Recamier model, high-waisted with a little top hugging the breasts, and a skirt long to the floor and straight in the front, sweeping out behind to make a short train.

Most people smiled politely and appeared to attribute it all to youth and impudence. Skirts were just beginning to go down by dint of dipping in back or on the side. Waists were still around the hips. Yet almost anyone who’d been following style the last few years must have realized that the natural waist was already practically accepted, the long skirt the obvious desire of the women. They had come around to the point where freedom and masculinity were no longer one and the same thing in their minds. They had proven they could be free in the 1920s with their straight, shapeless clothes and now they were ready to be feminine again.

The catch was, of course, that although this was apparent in France where there were many designers working out their new ideas and trying them out slowly, in America there were practically no designers. And the American buyers were funny people. They always bought the new version of what they had already seen the season before. They never even looked at the really new things.

To call a fashion wearable is the kiss of death. No new fashion worth its salt is ever wearable.

—Eugenia Sheppard, 1960Manufacturers and department stores are not in business to experiment. They are in business to make money. In the realm of clothes they are very happy to have the French couturier experiment. When the couturier has become certain of what he is doing, when he puts out 80 percent of his collection with natural waistlines, then the stores buy them. Then the manufacturers see and buy them. Then the ready-made lady can have a version of them.

The stupidity of it is that the manufacturers don’t try to see, or are incapable of seeing, the seeds of what is to follow in each new collection of clothes. This is the reason that when whole collections of long skirts came out in France in 1930, the manufacturers were appalled. They let it be known that there had been a revolution in fashion, a spontaneous burst of long skirts in the midst of a short-skirted world.

This was sheer nonsense. I had observed it all coming along in France in 1928 before I left Paris. I wasn’t making any wild childish bet when I put in my “1930, surely” dress. The manufacturers, as a group, have about as little idea of what’s going on in the world as two-year-old children. The French legend had them by the neck in those days. It still has.

Elizabeth Hawes

From Fashion Is Spinach. Born in Ridgewood, New Jersey, in 1903, Hawes sailed for Paris shortly after graduating from Vassar and went to work at a dressmaker’s shop making illegal knockoffs of fashion-house designs. She served as a correspondent for American newspapers and became a fashion buyer for Macy’s; in 1928 Hawes returned to New York City and opened one of the first American ateliers to design gowns to order. Ten years later she published her first book, Fashion Is Spinach, a declaration of independence from European style.