Socrates: Our next task must be to make marriage as sacred as possible. And the sacred marriages will be those that are most beneficial.

Glaucon: Absolutely.

Socrates: How, then, will they be most beneficial? Tell me this, Glaucon: I see that you have hunting dogs and quite a flock of noble fighting birds at home. Have you noticed anything about their mating and breeding?

Glaucon: Like what?

Socrates: In the first place, although they’re all noble, aren’t there some that are the best and prove themselves to be so?

Glaucon: There are.

Socrates: Do you breed them all alike, or do you try to breed from the best as much as possible?

Glaucon: I try to breed from the best.

Socrates: And do you breed from the youngest or the oldest or from those in their prime?

Glaucon: From those in their prime.

Socrates: And do you think that if they weren’t bred in this way, your stock of birds and dogs would get much worse?

Glaucon: I do.

Socrates: What about the horses and other animals? Are things any different with them?

Glaucon: It would be strange if they were.

Socrates: Dear me! If this also holds true of human beings, our need for excellent rulers is indeed extreme.

Glaucon: It does hold of them. But what of it?

Socrates: Because our rulers will then have to use a lot of drugs. And while an inferior doctor is adequate for people who are willing to follow a regimen and don’t need drugs when drugs are needed, we know that a bolder doctor is required.

Glaucon: That’s true. But what exactly do you have in mind?

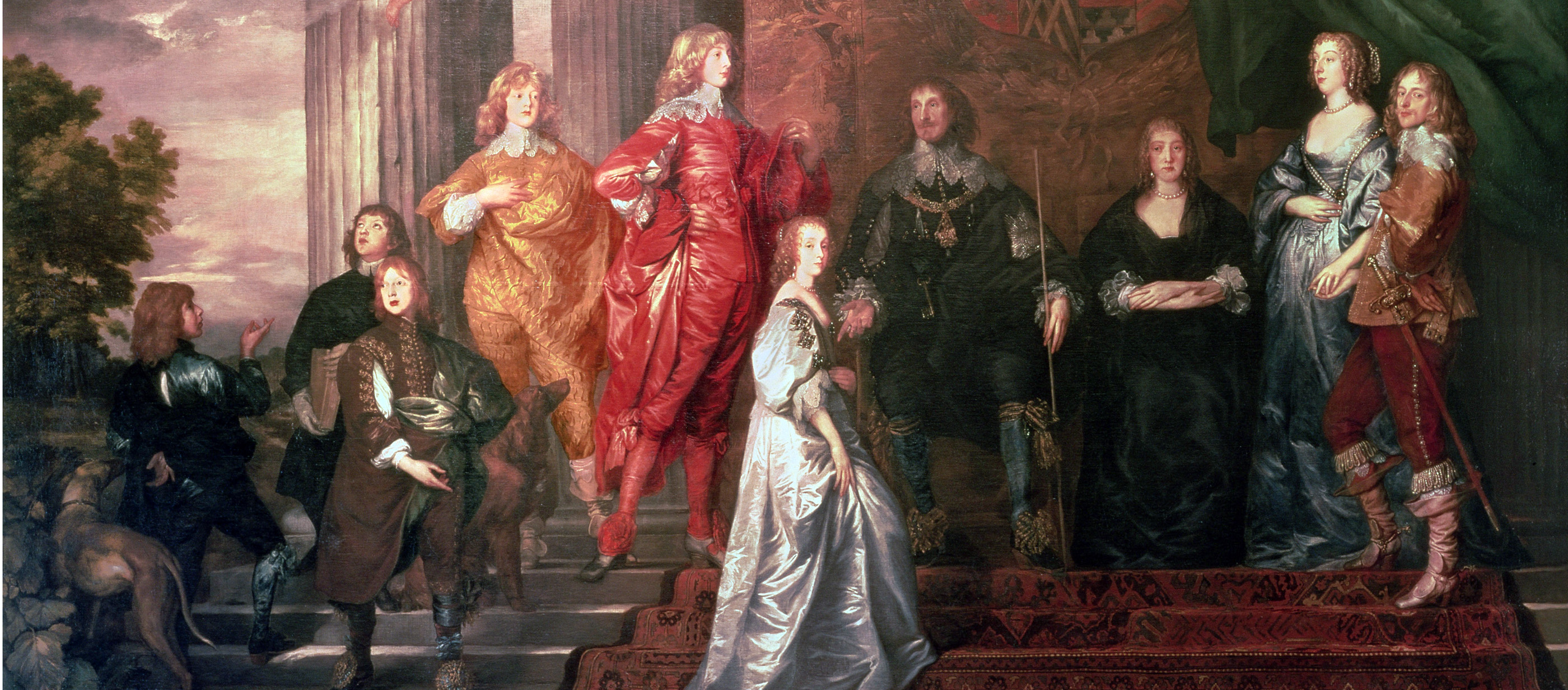

The Natchez, by Eugène Delacroix, 1835. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Purchase, Gifts of George N. and Helen M. Richard and Mr. and Mrs. Charles S. McVeigh and Bequest of Emma A. Sheafer, by exchange.

Socrates: I mean that it looks as though our rulers will have to make considerable use of falsehood and deception for the benefit of those they rule. And we said that all such falsehoods are useful as a form of drug?

Glaucon: And we were right.

Socrates: Well, it seems we were right, especially where marriages and the producing of children are concerned.

Glaucon: How so?

Socrates: It follows from our previous agreements, first, that the best men must have sex with the best women as frequently as possible, while the opposite is true of the most inferior men and women, and second, that if our herd is to be of the highest possible quality, the former’s offspring must be reared but not the latter’s. And this must all be brought about without being noticed by anyone except the rulers, so that our herd of guardians remains as free from dissension as possible.

Glaucon: That’s absolutely right.

Socrates: Therefore certain festivals and sacrifices will be established by law at which we’ll bring the brides and grooms together, and we’ll direct our poets to compose appropriate hymns for the marriages that take place. We’ll leave the number of marriages for the rulers to decide, but their aim will be to keep the number of males as stable as they can, taking into account war, disease, and similar factors, so that the city will, as far as possible, become neither too big nor too small.

Glaucon: That’s right.

Socrates: Then there’ll have to be some sophisticated lotteries introduced, so that at each marriage the inferior people we mentioned will blame luck rather than the rulers when they aren’t chosen.

Glaucon: There will.

Socrates: And among other prizes and rewards, the young men who are good in war or other things must be given permission to have sex with the women more often, since this will also be a good pretext for having them father as many of the children as possible.

Glaucon: That’s right.

Socrates: And then, as the children are born, they’ll be taken over by the officials appointed for the purpose, who may be either men or women or both, since our offices are open to both sexes.

Glaucon: Yes.

Socrates: I think they’ll take the children of good parents to the nurses in charge of the rearing pen situated in a separate part of the city, but the children of inferior parents, or any child of the others that is born defective, they’ll hide in a secret and unknown place, as is appropriate.

Glaucon: It is, if indeed the guardian breed is to remain pure.

Socrates: And won’t the nurses also see to it that the mothers are brought to the rearing pen when their breasts have milk, taking every precaution to insure that no mother knows her own child and providing wet nurses if the mother’s milk is insufficient? And won’t they take care that the mothers suckle the children for only a reasonable amount of time and that the care of sleepless children and all other such troublesome duties are taken over by the wet nurses and other attendants?

Glaucon: You’re making it very easy for the wives of the guardians to have children.

Socrates: And that’s only proper. So let’s take up the next thing we proposed. We said that the children’s parents should be in their prime.

Glaucon: True.

Socrates: Do you share the view that a woman’s prime lasts about twenty years and a man’s about thirty?

Glaucon: Which years are those?

Socrates: A woman is to bear children for the city from the age of twenty to the age of forty, a man from the time that he passes his peak as a runner until he reaches fifty-five.

Glaucon: At any rate, that’s the physical and mental prime for both.

Socrates: Then if a man who is younger or older than that engages in reproduction for the community, we’ll say that his offense is neither pious nor just, for the child he begets for the city, if it remains hidden, will be born in darkness, through a dangerous weakness of will, and without the benefit of the sacrifices and prayers offered at every marriage festival, in which the priests and priestesses together with the entire city ask that the children of good and beneficial parents may always prove themselves still better and more beneficial.

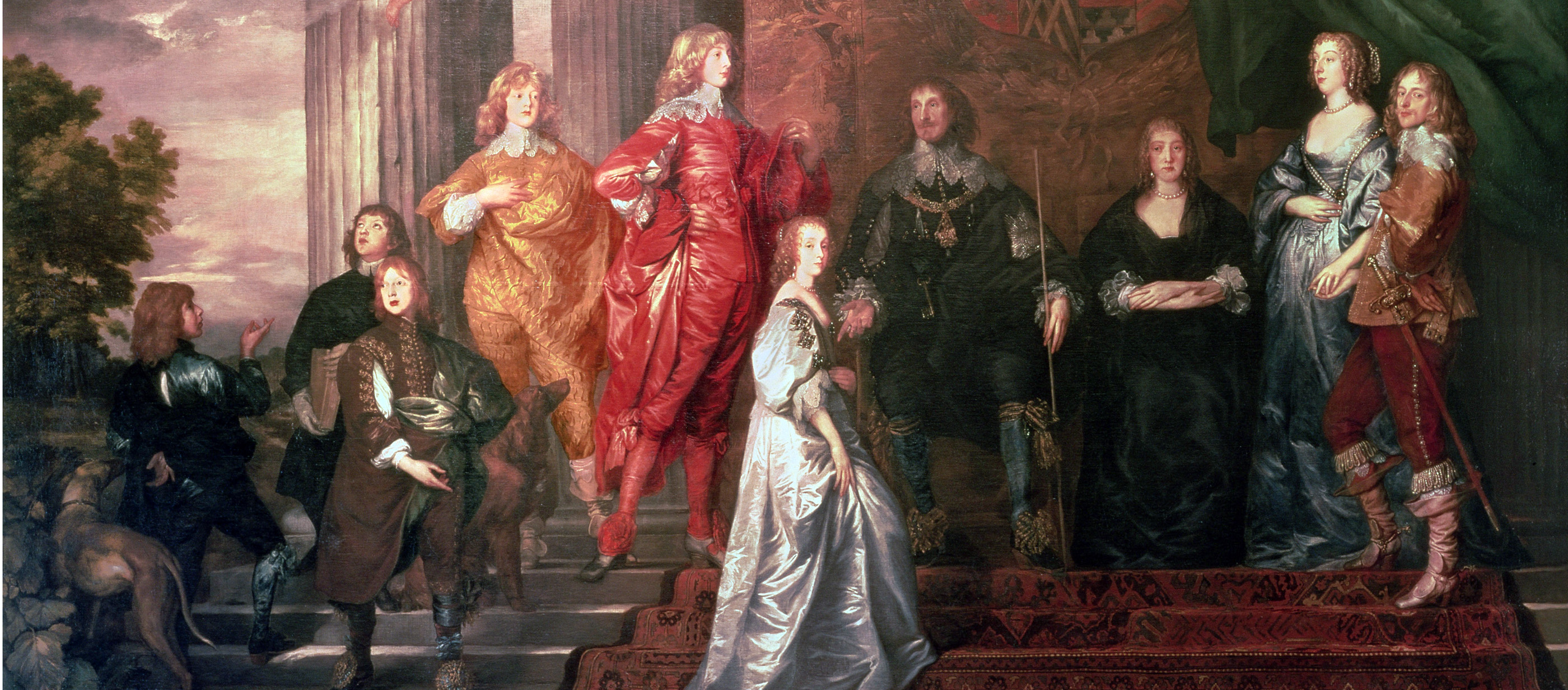

Philip Herbert, Fourth Earl of Pembroke, and His Family, by Sir Anthony van Dyck, c. 1635. The Earl of Pembroke’s Collection.

Glaucon: That’s right.

Socrates: The same law will apply if a man still of begetting years has a child with a woman of childbearing age without the sanction of the rulers. We’ll say that he brings to the city an illegitimate, unauthorized, and unhallowed child.

Glaucon: That’s absolutely right.

Socrates: However, I think that when women and men have passed the age of having children, we’ll leave them free to have sex with whomever they wish, with these exceptions: for a man—his daughter, his mother, his daughter’s children, and his mother’s ancestors; for a woman—her son and his descendants, her father and his ancestors. Having received these instructions, they should be very careful not to let a single fetus see the light of day, but if one is conceived and forces its way to the light, they must deal with it in the knowledge that no nurture is available for it.

Glaucon: That’s certainly sensible. But how will they recognize their fathers and daughters and the others you mentioned?

Socrates: They have no way of knowing. But a man will call all the children born in the tenth or seventh month after he became a bridegroom his sons, if they’re male, and his daughters, if they’re female, and they’ll call him father. He’ll call their children his grandchildren, and they’ll call the group to which he belongs grandfathers and grandmothers. And those who were born at the same time as their mothers and fathers were having children they’ll call their brothers and sisters. Thus, as we were saying, the relevant groups will avoid sexual relations with each other. But the law will allow brothers and sisters to have sex with one another if the lottery works out that way and the Pythia approves.

Glaucon: That’s absolutely right.

© 1992 by Hackett Publishing Company, Inc. Used with permission of Hackett Publishing Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

Plato, from The Republic. With his father claiming descent from the last king of Athens and his mother related to leaders of the oligarchy of 404 bc, Aristocles became known by his nickname “Plato,” after the Greek word “platus,” meaning “broad.” It is thought that the name was given to him in his youth, either in reference to his expansive forehead or robust build. The philosopher is said to have left Athens after Socrates was killed in 399 bc, traveled to Italy and Egypt, and returned home twelve years later to found the Academy.

Back to Issue