Lord! I wonder what fool it was that first invented kissing.

—Jonathan Swift, 1738Fear and Loathing

How the Kinsey Reports forever altered America’s sexual landscape—and not for the better.

By Dagmar Herzog

The project staff of the Institute for Sex Research, Alfred C. Kinsey seated center, Indiana University, August 1953. Science Service, Records, 1920s–1970s, Smithsonian Institution Archives.

Sixty years ago, Alfred Kinsey, a professor of zoology at Indiana University, published Sexual Behavior in the Human Male, an 804-page tract documenting impressively high rates of non-normative behavior among ordinary Americans, including widespread premarital intercourse, marital infidelity, homosexuality, and masturbation. The report made a ponderous pretense at being value-free.

The scientific facade fooled no one. Despite Kinsey’s numerous assertions that he was merely an empiricist, the disclaimers were disingenuous. A polemicist with a strongly sex-affirmative and antiguilt agenda, he was intent upon proving that many if not most American men deviated significantly from the social rules governing sexual behavior, and that had their transgressions been discovered, quite a few of them would have been found guilty of breaking a law. Kinsey’s take-home message outraged the defenders of bourgeois rectitude, whose hysterical indignation was contemporary with the intensification of the Cold War, the rise of aggressive McCarthyism, and the escalated emphasis on conservative family values and gender roles. Five years later, it was no surprise when the publication of Kinsey’s companion volume Sexual Behavior in the Human Female (asserting, among other things, that a woman’s capacities for orgasm and marital infidelity were essentially no different from a man’s) was met with a storm of objection in the media that successfully laid waste to the zoologist’s credibility and funding.

If in America the Kinsey Reports sold into the markets for prudery as well as prurience (the voyeuristic fascination inseparable from the moral outrage), the European response—especially among West German, French, and Swiss journalists, sociologists, and theologians—is less well known. It was also one of horror—not at the prevalence of sexual activity, but rather at what was perceived to be an utter lack of genuine sensuality in American culture. As a Swiss psychoanalyst put it in his critique of the Kinsey Reports, “Everything exudes an air of numbed lovelessness.”

European commentators were aghast. In erotic terms, the United States was a frightful wasteland: the women were apparently frigid, the men sexually inept. The American “dating game” was said to epitomize a culture of rampant competitiveness and superficiality. Single females needed to enhance and falsify their breast size to achieve any sexual self-esteem at all, and married women found their only fulfillment in the success of their husbands’ business careers. To European eyes, the version of Protestantism that dominated the American scene instilled sexual inhibition in men and women alike; the distinctly American premarital activity known as “petting” was seen not as a clever compromise that permitted mutual orgasm without the risk of pregnancy but as yet another sign of the sex-negativity of American culture. With a zeal that can only be read as schadenfreude, Europeans described the chief military and ideological victors of World War II as pathetically lacking in erotic imagination and playfulness. Above all, they emphasized that there was something sad (as opposed to threatening) in the world Kinsey envisioned.

Rolla, by Henri Gervex, 1878. Musée des Beaux-Arts Bordeaux, France.

Europeans fixed on something that many Americans had not. Kinsey counted orgasms the way other people counted beans or pennies or cars on the highway: he considered orgasms (or “sexual outlets” as he called them) equivalent units that could be added, subtracted, and compared. The problem with Kinsey, his Europeans critics contended, was that he never thought about the quality of the orgasm, only its quantity. And he never thought at all about love.

In 1955, the French journal Esprit accused Kinsey of deromanticizing sex with his mindless fixation on “outlet” statistics and his “rudimentary” understanding of sexual passion. What Kinsey seemed unable to imagine, the French critics argued, was that emotions mattered just as much as, if not more than, the “machine-like” manipulation of another person’s genitals. “The desire to know the other, the vertigo of curiosity” about one’s partner: that was the decisive ingredient at the moment of orgasm that defined great lovemaking. Rather than finding genuine communion and “something precious to exchange,” the “human animals” that Kinsey described could seek at best a “spasm of consolation.” “Lacking all love, all tenderness,” there was nothing but the contact between skin and skin, between “autonomous nerves.” This, Esprit concluded, was truly solitude à deux: deep loneliness in the midst of sexual activity. When Americans had sex with each other, they were really just having sex with themselves. Esprit could hardly have guessed that someday—on the other side of the sexual revolution that Kinsey had helped initiate—these same perceptive criticisms would be used not only to market an endless stream of sex advice and sex aids (both mechanical and chemical) but also to prompt the suppression of sexual liberty.

The sexual revolution that Kinsey anticipated did indeed undermine the blatant hypocrisy that characterized the fifties. After all—as Kinsey’s tomes so scrupulously showed—the culture that existed before the sexual revolution had hardly been free of promiscuity and adultery. Both were rampant, but it was the man’s part in the play, not the woman’s, that the hypocrisy had served. Women were often the ones who had to pay for nonmarital sex: not with money, but with shame, unwanted pregnancies, and dangerous abortions. And within marriage, women were obliged to tolerate their husbands’ sexual escapades. However incompletely, the sexual revolution leveled the playing field for women and brought social norms, laws, and behavior into greater alignment. It made talk about sex more open and contraception more readily available, and brought forth more challenges to the false pieties surrounding premarital chastity. But the sexual revolution also created anxieties—not only about the newfound sense of freedom, but also about precisely the two concerns that Kinsey had overlooked: the quality of physical pleasure and the nature of passionate love.

When the Kinsey Reports had first been published, and Americans were able to learn about other people’s sex lives, the effect was primarily one of overwhelming relief. People discovered that they were far from alone in their secret deviance from the socially approved mores. But as the sexual revolution unfolded over the next several decades, incessant chatter and graphic imagery about the intimate details of other people’s sex lives began to cause tremendous insecurity. Someone somewhere had a more ardent, more adoring, more adept lover than you. Someone somewhere had a more agile tongue; a more fluent, sensational touch; a better knowledge of just what to do with the frenulum and the perineum, the nipples and the G-spot. Someone somewhere was having an easier time reaching those explosive orgasms that always eluded you. Someone somewhere was having better sex. Americans were endlessly comparing themselves to others and finding themselves—or their partners—wanting. The resulting feelings of inadequacy created a huge market for assistive technologies, from vibrators to porn to pharmaceutical remedies.

When Viagra arrived in the spring of 1998, the pill’s manufacturer, Pfizer Incorporated, was rewarded with an astonishing bonanza. Sales in its first year topped $1 billion, and by 2001, Pfizer had become the largest and most powerful drug company in the world and the fifth most profitable company in the United States. By 2003, Pfizer boasted that nine men around the world were ingesting a Viagra pill every second. Meanwhile, the indicated uses for Viagra were expanded to include not only erectile dysfunction but also erectile dysphoria, defined as a “vague sense of dissatisfaction with one’s erection.” Reports circulated that this condition afflicted fully 50 percent of the male population between the ages of forty and seventy. By 2006, perfectly healthy men were using Viagra just “to jazz things up.”

Almost immediately, the search for a so-called “pink Viagra” was on. It was only sensible that Pfizer and its rivals would try to develop a product for the other half of the human race. In 2000, the Food and Drug Administration affixed its seal of approval to the medicalization of female dissatisfaction with sex when it issued draft guidelines for the treatment of a newly diagnosable disease entity: female sexual dysfunction (FSD). The FDA broke the disease down into four subcategories: low levels of desire (thoughts, longings), low levels of physiological arousal (blood flow, lubrication), difficulty reaching orgasm (formerly known as frigidity), and pain with intercourse. The definition of FSD was soon broadened by experts and pharmaceutical companies to include women’s disappointment with orgasms perceived to be inadequately intense (or too “muffled.”) An utterly hallucinatory invention—situated at the border between normalcy and abnormalcy, biochemistry and the emotions—FSD soon came to be felt by many as all too real.

The hallucination produced yet another market for fear and loathing. Just when desire seemed to be something that could be turned on and off, the American news media found themselves worrying about the death of desire itself. Where had all the libido gone? Reports surfaced indicating that millions of Americans were trapped in “no-sex” or “low-sex” marriages, that one in three women and one in six men had little or no desire for sex, and that it was often the husbands who were “too tired” or simply not interested. Even the perennially oversexed Cosmopolitan felt obliged to offer its readers tips on what to do “When His Sex Drive Takes a Nosedive.” Magazines for more mature women urged wives to “surrender in the bedroom,” to offer their stressed husbands “quickies” in order not to lose their men’s interest entirely and, as Redbook put it, to “have sex—even when you don’t want to!” Sex counselors and advice columnists made a fortune publishing books with titles like Resurrecting Sex, The Sex-Starved Marriage, Rekindling Desire, and In the Mood, Again. And once pharmaceutical companies discovered that Viagra equivalents were not going to work for women (perhaps because female arousal in the form of vaginal lubrication functions differently from the genital blood flow that Viagra provides men), yet another new disease entity was fabricated: hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD), defined as “decreased interest in sex.” Once again, the media rushed into the fray. “Orgasm: How Science Can Help,” blared Psychology Today. “Let’s Talk about Sex—and Drugs,” boomed Science.

The effect of the hype was to heighten people’s anxiety about whether the sex they were having was as perfect as it could be and—crucially—whether it was emotionally meaningful. For the first time since Europeans shuddered at the world uncovered by Kinsey, sex sellers of all stripes worried about how to peddle that unpurchasable product called love. Without emotion, even a thunderous orgasm could leave you feeling disconnected and empty.

Social conservatives, ever on the lookout for opportunities to exploit people’s insecurities about intimacy, welcomed the arrival of the George W. Bush’s administration as an opportunity to advance a comprehensive crusade against premarital sex. Emboldened by its capture of the White House, the Christian Right pushed to increase funding for a more aggressive campaign to inform young people that sex outside of marriage damaged one’s psychological health, precluded the possibility of academic or athletic success, lowered self-esteem, and led to miserable marriages. An intimidated populace acquiesced without much protest to this undignified—and ultimately dangerous—exercise. Americans had allowed themselves to become profoundly confused about why people bothered to have sex and whether they even enjoyed it when they did.

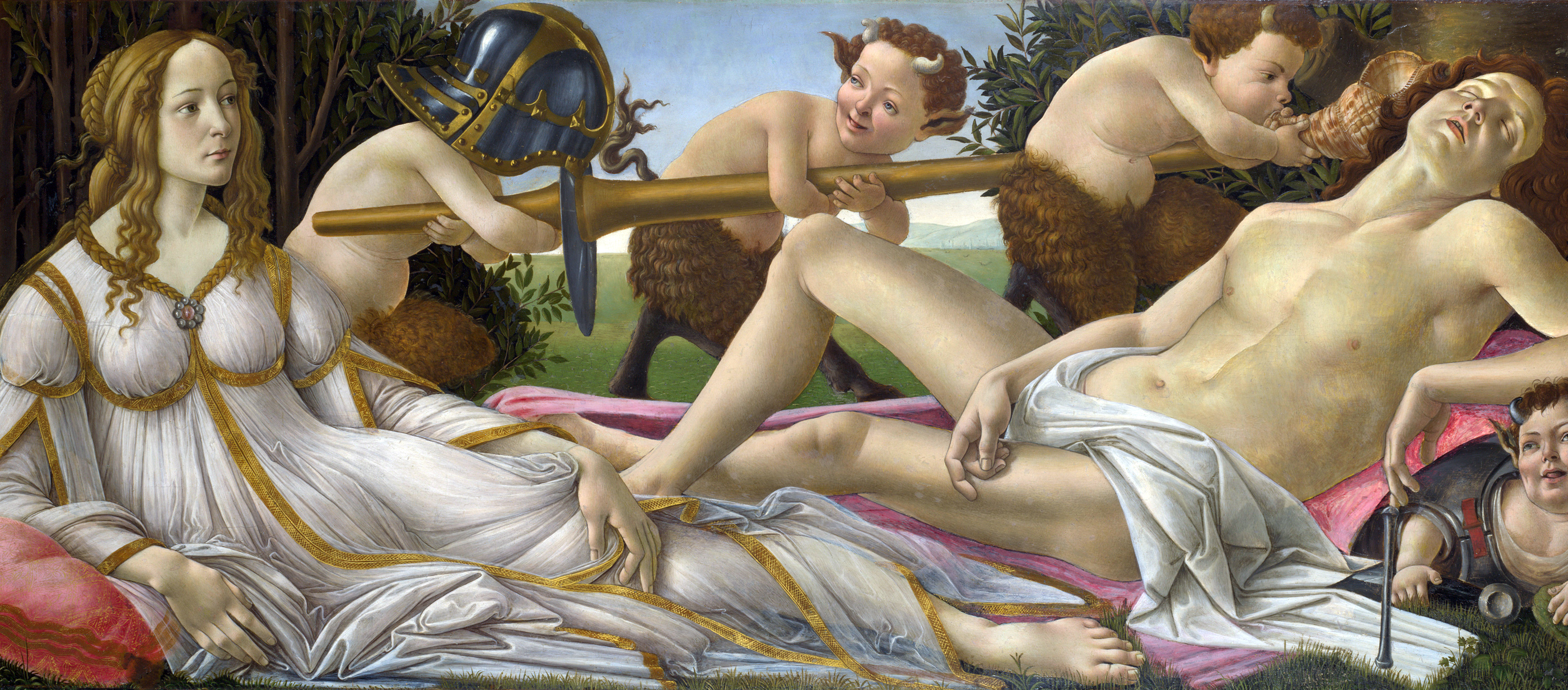

Mars and Venus, by Sandro Botticelli, c. 1485. National Gallery, London, England.

The pharmaceutical companies, the women’s magazine industry, and the sexual conservatives all had something in common: each offered Americans the elusive prize of deeper intimacy. All played deliberately on the ambivalence created by the unfulfilled promises of the sexual revolution, and capitalized on the anxiety generated in a society hypersaturated with sexual stimulation. Antiporn crusaders further refined their arguments to contend that even during sex, the husband was “masturbating inside [his wife’s] body while he is having sex with the women on the screen.” Men supposedly had lost the ability to make love; a wife had become a “masturbatory accessory.” In a similar vein, an enterprising group of evangelicals hit the jackpot with a series of books (replete with accompanying audiotapes, workbooks, and expensive weekend workshops) that gave men guidance on breaking their porn habit and redirecting their sexual desires to their flesh-and-blood spouses. The target audience was enormous. The fact that three million copies of these books were sold within seven years suggests the extent of the emotional pain gripping the American heartland.

The new moralists offered what religions have always offered: magic. They promised to provide the most physically intense orgasms and a profound sense of emotional connection with the partner. They pledged an end to the disappointment and estrangement apparently endemic to many people’s sexual experiences. They stoked confusion and fear about the potential perfectibility of sex. And they benefited greatly from the early twenty-first century phenomenon of Internet pornography that is constantly decried even as its audience continues to grow.

The evangelicals tapped into a cultural shift that sexologists and social scientists had noticed as well. Echoing the comments of Kinsey’s European critics from half a century ago, observers around the turn of the millennium began to speak of a frightening trend toward the “onanization of sex.” The orgasm was becoming a trophy of self-reassurance in the battle with another body, rather than the pleasurable byproduct of an interaction with another human being who was passionately desired for him or herself. Orgasm had become the sign that one could quit—that, thank goodness, a particular sexual episode was now over. The idea that sex might be a process rather than a goal-oriented task—that it might be a sensual, transformative, ongoing journey of discovery—had begun to seem quaint and unrealistic.

Both the pharmaceutical companies and the Christian moralists promise more pleasure, not less; they dangle the hope of boundary-dissolving ecstasy, fantastic orgasms, and intense connection. They are not antisex, but rather intent on heightening people’s anxieties about sex; they are interested in generating inner confusion and conflict, not clarity about the rules. They are not silent about sex, but rather talk of it constantly, and in ever more explicit terms. Yet by reducing sex to a mechanical exercise, they are killing the very thing they claim to provide. For the survival of Eros depends on leaving the core legacy of the sexual revolution unresolved: the nebulous intersection of sex and love, the hidden place where bodies and emotions meet.

In today’s sexual wasteland, there are nonetheless grounds for optimism. The electric erotic charge that infuses durable partnerships and fleeting flirtations, meaningful work and abandoned play, political courage and selfless caring, remains palpable for many people. And despite all efforts to dissect him, pimp him, or eulogize his premature demise, Eros continues to show up unannounced—disheveled, but as beautiful as ever—and in the most unexpected places. There is no advice column, drug, technique, or technology that can make us kiss with outrageous sensuousness or generate that delicious “vertigo of curiosity” about another person that suffuses life with wild joy. When it happens—and it does—it is not within our control. It is pure grace.