Once you hear the details of a victory it is hard to distinguish it from a defeat.

—Jean-Paul Sartre, 1951Goodbye to All That

Mary Shelley’s future plague.

Have any of you, my readers, observed the ruins of an anthill immediately after its destruction? At first it appears entirely deserted of its former inhabitants; in a little time you see an ant struggling through the upturned mold; they reappear by twos and threes, running hither and thither in search of their lost companions. Such were we upon the earth, wondering aghast at the effects of pestilence. Our empty habitations remained, but the dwellers were gathered to the shades of the tomb.

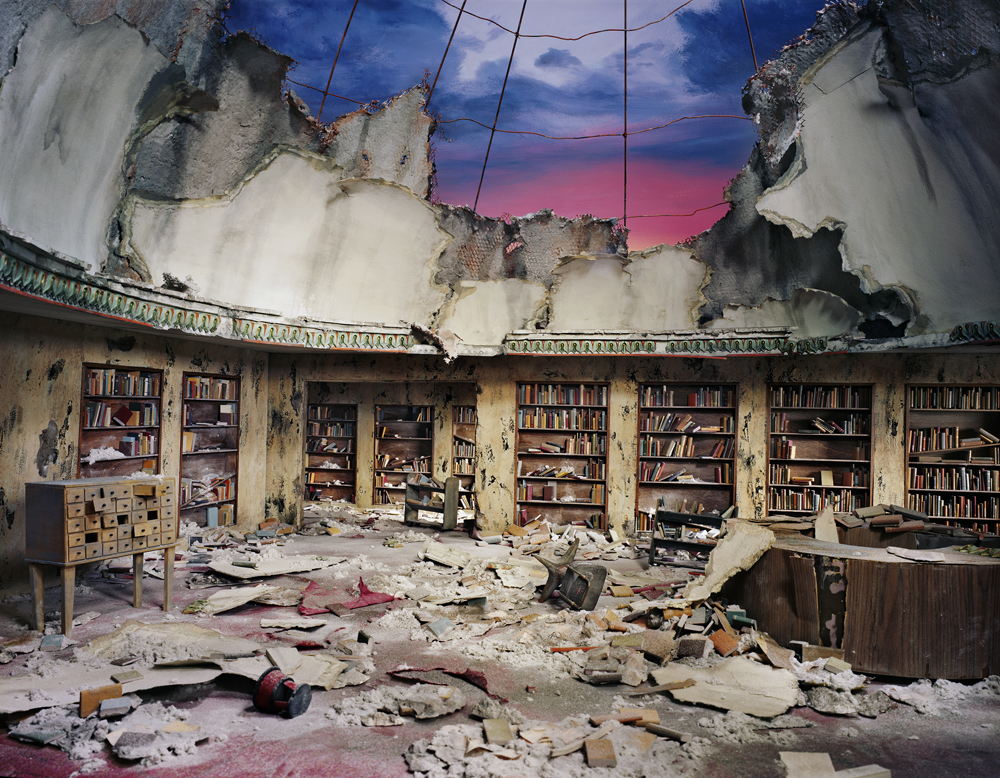

As the rules of order and pressure of laws were lost, some began with hesitation and wonder to transgress the accustomed uses of society. Palaces were deserted, and the poor man dared at length, unreproved, intrude into the splendid apartments, whose very furniture and decorations were an unknown world to him. It was found that, though at first the stop put to all circulation of property, had reduced those before supported by the factitious wants of society to sudden and hideous poverty, yet when the boundaries of private possession were thrown down, the products of human labor at present existing were more, far more, than the thinned generation could possibly consume. To some among the poor this was matter of exultation. We were all equal now; magnificent dwellings, luxurious carpets, and beds of down were afforded to all. Carriages and horses, gardens, pictures, statues, and princely libraries, there were enough of these even to superfluity; and there was nothing to prevent each from assuming possession of his share. We were all equal now; but near at hand was an equality still more leveling, a state where beauty and strength, and wisdom, would be as vain as riches and birth. The grave yawned beneath us all, and its prospect prevented any of us from enjoying the ease and plenty which in so awful a manner was presented to us.

Circulation Desk, by Lori Nix, 2012. Archival pigment print, 30 x 40 inches. Courtesy the artist and Clamp Art Gallery, NYC.

Where could we turn and not find a desolation pregnant with the dire lesson of example? The fields had been left uncultivated, weeds and gaudy flowers sprung up—or where a few wheat fields showed signs of the living hopes of the husbandman, the work had been left halfway, the plowman had died beside the plow; the horses had deserted the furrow, and no seedsman had approached the dead; the cattle unattended wandered over the fields and through the lanes; the tame inhabitants of the poultry yard, balked of their daily food, had become wild—young lambs were dropped in flower gardens, and the cow stalled in the hall of pleasure. Sickly and few, the country people neither went out to sow nor reap, but sauntered about the meadows, or lay under the hedges, when the inclement sky did not drive them to take shelter under the nearest roof. Many of those who remained secluded themselves; some had laid up stores which should prevent the necessity of leaving their homes—some deserted wife and child, and imagined that they secured their safety in utter solitude. Such had been one man’s plan, and he was discovered dead and half-devoured by insects, in a house many miles from any other, with piles of food laid up in useless superfluity. Others made long journeys to unite themselves to those they loved, and arrived to find them dead.

London did not contain above a thousand inhabitants, and this number was continually diminishing. Most of them were country people, come up for the sake of change; the Londoners had sought the country. The busy eastern part of the town was silent, or at most you saw only where, half from cupidity, half from curiosity, the warehouses had been more ransacked than pillaged: bales of rich India goods, shawls of price, jewels, and spices, unpacked, strewn the floors. In some places the possessor had to the last kept watch on his store and died before the barred gates. The massy portals of the churches swung creaking on their hinges, and some few lay dead on the pavement. The wretched female, loveless victim of vulgar brutality, had wandered to the toilet of high-born beauty and, arraying herself in the garb of splendor, had died before the mirror which reflected to herself alone her altered appearance. Women whose delicate feet had seldom touched the earth in their luxury had fled in fright and horror from their homes till, losing themselves in the squalid streets of the metropolis, they had died on the threshold of poverty.

The hunger of Death was now stung more sharply by the diminution of his food; or was it that before, the survivors being many, the dead were less eagerly counted? Now each life was a gem, each human breathing form of far, oh far more worth than subtlest imagery of sculptured stone; and the daily, nay, hourly decrease visible in our numbers visited the heart with sickening misery. This summer extinguished our hopes, the vessel of society was wrecked, and the shattered raft, which carried the few survivors over the sea of misery, was riven and tempest tossed. Man existed by twos and threes; man, the individual who might sleep and wake and perform the animal functions; but man, in himself weak, yet more powerful in congregated numbers than wind or ocean; man, the queller of the elements, the lord of created nature, the peer of demigods, existed no longer.

Farewell to the patriotic scene, to the love of liberty and well-earned meed of virtuous aspiration! Farewell to crowded senate, vocal with the councils of the wise, whose laws were keener than the sword blade tempered at Damascus! Farewell to kingly pomp and warlike pageantry; the crowns are in the dust, and the wearers are in their graves! Farewell to the desire of rule, and the hope of victory; to high vaulting ambition, to the appetite for praise, and the craving for the suffrage of their fellows! The nations are no longer! No senate sits in council for the dead; no scion of a time-honored dynasty pants to rule over the inhabitants of a charnel house; the general’s hand is cold, and the soldier has his untimely grave dug in his native fields, unhonored, though in youth. The marketplace is empty, the candidate for popular favor finds none whom he can represent. To chambers of painted state farewell! To midnight revelry, and the panting emulation of beauty, to costly dress and birthday show, to title and the gilded coronet, farewell!

Farewell to the giant powers of man—to knowledge that could pilot the deep-drawing bark through the opposing waters of shoreless ocean, to science that directed the silken balloon through the pathless air, to the power that could put a barrier to mighty waters, and set in motion wheels and beams and vast machinery, that could divide rocks of granite or marble and make the mountains plain!

The Prairie Burial, by William Ranney, 1848. © Buffalo Bill Center of the West / The Art Archive at Art Resource.

Farewell to the arts—to eloquence, which is to the human mind as the winds to the sea, stirring and then allaying it. Farewell to poetry and deep philosophy, for man’s imagination is cold, and his inquiring mind can no longer expatiate on the wonders of life, for “there is no work, nor device, nor knowledge, nor wisdom in the grave whither thou goest!”—to the graceful building, which in its perfect proportion transcended the rude forms of nature! Farewell to sculpture, where the pure marble mocks human flesh, and in the plastic expression of the culled excellencies of the human shape shines forth the god! Farewell to painting, the high wrought sentiment and deep knowledge of the artist’s mind in pictured canvas! Farewell to music, and the sound of song, to the marriage of instruments, where the concord of soft and harsh unites in sweet harmony and gives wings to the panting listeners, whereby to climb heaven and learn the hidden pleasures of the eternals! Farewell to the well-trod stage; a truer tragedy is enacted on the world’s ample scene that puts to shame mimic grief. To high-bred comedy and the low buffoon, farewell! Man may laugh no more.

Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley

From The Last Man. A science-fiction novel published in 1826, The Last Man purports to tell of a late twenty-first-century England consumed by plague. Even though it was one of the Frankenstein author’s favorite books, The Last Man was met with critical derision upon publication—“the offspring of a diseased imagination, and of a most polluted taste,” read one contemporary review—and only sporadically kept in print until a 1965 American edition. Shelley died in London in 1851 at the age of fifty-three.