What keeps the democracy alive at all but the hatred of excellence, the desire of the base to see no head higher than their own?

—Mary Renault, 1956Our Chief Danger

The story of the democratic movements that the framers of the U.S. Constitution feared and sought to suppress.

By William Hogeland

Liberty Bell Brought to Allentown (detail from mural study for Allentown, Pennsylvania Post Office), by Gifford Beal, 1938. Smithsonian American Art Museum, transfer from the General Services Administration, 1974.

On the morning of May 29, 1787, in the Pennsylvania State House in Philadelphia, Edmund Randolph, governor of Virginia, opened the meeting that would become known as the Constitutional Convention by identifying the underlying cause of various problems that the delegates of thirteen states had assembled to solve. “Our chief danger,” Randolph declared, “arises from the democratic parts of our constitutions.” None of the separate states’ constitutions, he said, had established “sufficient checks against the democracy.”

The room was full of political elites from around the country, painfully aware of recent advances against the interests of the wealthy by what Randolph called democracy. Far from opposing ordinary people’s agitation for political equality, some state legislatures had even been active on the people’s behalf, devaluing revolving high-interest loans and thus hurting merchants and big landowners. Nor were the wealthy being paid an anticipated 6 percent interest on their financial investment in the War of Independence. Shays’ Rebellion, an armed uprising against taxing ordinary citizens to bail out the lending and investing class, had frightened the Massachusetts legislature so badly that it repealed the taxes and pardoned the rebels.

Meanwhile, the Pennsylvania assembly, once the most august in America, was now full of representatives of the formerly disenfranchised. In the very building where Randolph was addressing the convention, that assembly had shut down a Philadelphia bank on the grounds that it financed only its partners’ speculations and denied small farmers credit, calling the bank’s charter the property of the people, not the bankers; it was also contemplating a war-debt payoff that would erase profits for investors. There were similar movements all over the country. Nervous elites worried that private property would eventually be seized and redistributed. They could do little about it. Such were the “imbecilities,” as Randolph put it to the delegates, of the Articles of Confederation that united the states.

But he had a solution. Dispense with the confederation, Randolph urged the room, and form a national government. General George Washington, chair of the convention, agreed; so did James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, and many more. Some of the delegates disliked certain specifics of the solution that Randolph proposed. Others were leery of forming a national government at all. Famous debates proceeded, but the delegates never debated the nature of the danger they faced. It was democracy. They’d gathered in Philadelphia to defeat it.

What the delegates meant by the word democracy could vary. People sometimes used the word to mean “the mob,” short for mobile vulgus, an excitable crowd: protest, riot, and violence by people denied legal access to power. But sometimes democratic referred to nothing more violent or radical than lawmaking by an elite legislative body that was overly sensitive to the desires of its elite constituents. There are only a few examples of the term’s having positive connotations. Patrick Henry once said that he was coming around to becoming a John Adams–type democrat, yet nobody more harshly disparaged what he labeled “democratical” schemes than Adams himself.

What Adams meant is a government too susceptible to ordinary people’s influence. It’s sometimes claimed that when the founders condemned democracy, they meant only simple, direct democracy—referendum on every law and issue. Madison and others did write against direct democracy, but the democracy that Adams derided, and Randolph called the chief danger facing the country, and Madison recoiled from in his famous Federalist 10, had nothing to do with referendum. Representation is what those men worried about—a representation too broad and inclusive, creating state legislatures too responsive to ordinary people’s wishes, not sufficiently protective of the well-off. That situation had to change.

If the framers of the Constitution weren’t our founding democratic ancestors, and indeed created a Constitution designed to obstruct democracy, we can nonetheless find such ancestors among forces that the framers sought to shut down. The founding-era democratic movement, though obscure today, was strong. And it was just as American as its more famous opponents.

The long colonial period was marked by a struggle between American labor and small-scale enterprise on the one hand and American wealth on the other. If such a struggle seems anachronistically modern, that’s because today it’s so generally de-emphasized in favor of colonial Americans’ collective struggles against Britain, but within the colonies, less propertied white men—small farmers and artisans, tenants, laborers—were legally denied the vote, and it took even more property to stand for office. American merchants and landlords thus controlled the levers of government on their own behalf. The founding-era effort to achieve working-class equality wouldn’t pass for a democratic movement today: largely excluded were black people, women, and the indigenous. Yet the movement was radical in seeking to disconnect political participation from property ownership and demanding public controls over the power of wealth.

One of its main targets was the common practice of predatory lending. High-interest loans enriched the lending class and sent ordinary families into spirals of foreclosure, tenancy, and penury. Another target was the corruption built into government: long slates of tolls and taxes levied on a host of everyday transactions, empowering politicians’ crony appointees to rob the less fortunate for a cut of collections. The movement’s most immediate aims were thus to obstruct enforcement of laws favoring big planters and merchants and to pressure legislatures to enact measures favoring small and tenant farmers, artisans, and landless laborers.

To that end, they rioted. Blackening their faces to avoid being identified and to emphasize community over individuality, and dressing in outlandish garb—sometimes women’s dresses, sometimes imitations of indigenous people’s clothing—to appall authority, they seized courts and disrupted debt cases. They manhandled tax collectors. They enforced boycotts of foreclosure auctions. They tore down officials’ homes. They broke into jails and rescued debt prisoners. They cut down huge trees to block passage into their communities. Sometimes such actions did force legislatures to enact policies that helped ordinary people—by issuing paper currencies, for example, and making the paper legal tender. Paper depreciated, favoring poor debtors over the rich creditors forced to accept it as payment of interest and principal. For the most part, however, gains for democratic policies in the colonial period were only spasmodic and occasional.

Then in the 1760s and 1770s, amid the crisis with Britain, the working class saw a chance to gain more access to political power than it had ever possessed. Elite patriots needed mass support against British officialdom and at once encouraged and tried to restrain and direct the democratic activists. The crowds were often ahead of elites, envisioning American independence as a government working on behalf of ordinary people. In that tense and shifting dynamic, new leaders came to the fore. These idiosyncratic American characters were key players in American independence but are not household names today because they opposed the elitism of the founders whose names we do know.

The career of the flamboyant Thomas Young exemplifies the democratic movement’s startling acceleration in the 1760s and 1770s. Young grew up on a small farm in the remote foothills of the Catskill Mountains, near the Hudson River. He was an autodidact, poring over Greek and Latin texts at an early age and teaching himself the violin. By apprenticeship to a medical doctor, he became a doctor himself, a pioneer of vaccination. A fan of Voltaire, he was once threatened with expulsion from Dutchess County, New York, for publicly calling Jesus a knave and a fool. When tenant farmers in that county started rioting against the power of the great landlords, Young advised and supported them, taking the radical view that government shouldn’t just stop favoring wealth over labor but start favoring labor over wealth.

Such ideas were subversive. Young spent his life hounded from place to place, with an ill wife and growing family, in deepening poverty yet always defiant. He wound up in Boston just when it was becoming a hotbed of resistance to British government. Boston’s upscale patriot leaders didn’t like Young, but Samuel Adams appreciated his brains and vigor and sent him riding around the province in a successful effort to network the town meetings into a shadow government. In a career that might have fizzled into mere ranting or even imprisonment, Thomas Young became an American revolutionary.

Fleeing Boston ahead of British soldiers, Young and his family went to Philadelphia, where he met James Cannon, a quiet math teacher. Cannon had ideas about organizing labor even more ambitious than Young’s. With Christopher Marshall, a universalist pharmacist and lapsed Quaker, Cannon formed the American Manufactory. Its object was to compete with the Bettering House, long the only institution providing relief to the city’s many destitute families. Run by Quakers, the Bettering House took in families, segregated them by sex in dorms, and set them spinning, weaving, and dyeing textiles, supposedly improving them morally for the profit of the house. For those being bettered, there was often no way out. Cannon and Marshall started the Manufactory as a labor-friendly alternative. Families stayed together in their homes. Women spun on their own time and brought fabric to the factory for dyeing and weaving by men employed there. Workers sat on the company’s board.

As the Manufactory started beating the Bettering House in output, it became a school of labor education. While drinking a lot of coffee with Young, Marshall, and others, Cannon launched a plan to have the entire white male working class of Pennsylvania demand the vote. The imperial crisis was heating up. The militia would be critical to defending the province against British invasion, and militia privates were at once the poorest and the vast majority of the force. Cannon realized that if they were organized across all towns and counties as a single networked group—Thomas Young had learned from Samuel Adams how to do that—the privates might exert an irresistible, even revolutionary, influence. The Committee of Privates, as the province-wide network became known, emerged as the strongest political organization in Pennsylvania, to the shock and dismay of upscale patriots. But they needed the militia.

Allegory of Magnanimity, by Luca Giordano, c. 1670. © The J. Paul Getty Museum, digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program.

Not all of our founding-era democratic ancestors were rationalists like Young and Cannon. The mystic Herman Husband had perhaps the furthest-reaching vision of American democracy. Having grown up a pampered and willful child on his parents’ Maryland plantation, he walked away from slaveholding, denouncing the institution as an abomination; away from the Anglican communion, denouncing it as spiritually dead; and away from the dedication to wealth that unified his class. He became a Quaker, though only temporarily (he was kicked out for questioning its dogma, too), and an abolitionist and apostle of nonviolent protest. By the 1760s he was living in the western wilds of North Carolina, a full-time activist against the creditor class and the corruption of government.

Because Husband was both land-rich and a democratic idealist, he served as a bridge between the truly poor and the landowning class that could vote. His neighbors elected him to the North Carolina assembly in the provincial capital of New Bern, where he spoke so uncompromisingly against the corruption of the assembly that he was repeatedly jailed. Soon he was a leader of the North Carolina Regulation, an uprising that took over court towns, roughed up officials, and tore down buildings. Committed to pacifism, Husband tried to moderate the violence, but by the time the royal governor sent in troops, he was a marked man; he fled on horseback right before the Battle of Alamance. Some of the perpetrators were summarily hanged on the field of battle. Husband ran all the way to one of the remotest places in the country, the western slopes of the Pennsylvania Alleghenies. A fugitive from Crown justice, living under a variety of aliases, and soon joined in secret by his family, he became the first white person with major landholdings and a big farm in that part of the mountains. During his isolation, in the grip of biblically inspired visions, Husband began developing and writing down his plans for a unified American nation founded on egalitarian principles.

The national plan that Herman Husband devised in the wild western mountains does not resemble the U.S. Constitution written in 1787. It resembles the New Deal of the 1930s, the Great Society of the 1960s, and measures yet to be achieved even now. He proposed progressive taxation with high top marginal rates. He developed a publicly managed universal retirement plan. He wanted to take the country off the gold standard and establish a democratically accountable body to manage inflation. He set term limits for officeholders and called for the popular election of judges. He imagined universal basic income, including for women; privately, he pondered the awesome potential in people’s controlling their own reproduction. He supported abolition of slavery and efforts at fairness for indigenous people.

The fact that Herman Husband hasn’t been taken up by modern progressives as the founding father of American social-contract liberalism and equal rights may be explained in part by his plan’s inspiration in spiritual revelation, but his neighbors in the quickly growing mountain community didn’t see that as a problem. They looked to him for leadership. In the 1770s Husband began to take on the same corruption in Pennsylvania government that had inspired the North Carolina Regulation. It wouldn’t be long before he’d be taking on Alexander Hamilton and George Washington.

Thomas Paine, the only one of the founding democratic leaders well known today, is too often remembered outside the democratic-activist context in which he thrived. An English working-class intellectual with a religious degree of passion for reason, Paine had failed in all prior endeavors when he arrived in Philadelphia late in 1774 and connected with Thomas Young, James Cannon, Christopher Marshall, and others in the city’s surging democratic movement. They soon took over the ad hoc patriot committees that ran the city and the province during the crisis. As the most powerful legislature in the country, the Pennsylvania assembly was blocking moves by a faction in the Continental Congress to declare independence: elite patriots in the assembly could see that in the event of a final break from Britain, these democratic outsiders were poised to take over Pennsylvania. Paine had done some writing before, but nothing like what he did now. Encouraged by his new friends, he started publishing essays and pamphlets, writing in a distinctive, authentic voice never heard before on behalf of American independence and against the Pennsylvania assembly’s position.

Paine wrote not only for independence but also for democracy; like Husband, he had higher regard for the rights of women and black and indigenous people than many others in the movement. Common Sense, the pamphlet that made Paine world famous, has been widely credited with tipping public opinion toward independence. In a section often ignored, Paine, like Husband, set out a plan for a national American government based on egalitarian principles. He argued for a broadly representative unicameral legislature, an executive committee, and direct judicial accountability to the people. John Adams hated Paine for gaining such a huge following for Common Sense and condemned Paine’s proposed form of national government as “democratical, without any restraint or even an attempt at any equilibrium or counterpoise” by elite interests. According to Adams, he and Paine had a shouting match over it.

I have often been convinced that a democracy is incapable of empire.

—Thucydides, 404 BCAnd yet Adams and Paine collaborated. Adams and his fellow antidemocratic elites in the Congress, who wanted a declaration of independence, had to work secretly with fervent democrats like Paine in the street to remove Pennsylvania as an obstacle to independence. In the summer of 1776, it was this devil’s bargain between elite privilege and democratic aspiration that brought about American independence. As Paine fired off pamphlets rousing ordinary Pennsylvanians, Adams passed congressional resolutions undermining the legitimacy of the mighty host government. At the end of June, when the militia’s Committee of Privates moved against the Pennsylvania assembly, the assembly succumbed to its armed working class in a bloodless coup. Opposition to American independence dissolved with it.

Everybody knows what happened next: the Congress adopted American independence. Less well-known is the new state constitution of Pennsylvania, which fulfilled and went beyond Paine’s prescriptions for democracy: no elite upper house; the executive power invested in a committee, elected by the one house; a democratically elected judiciary; and virtually no property qualifications for voting or holding office. In disconnecting property from rights, this was a truly revolutionary document. On its basis, Herman Husband was elected to the Pennsylvania assembly, and there began pushing for the untoward progressivism he’d envisioned during his years in the wilderness. A fundamental divergence of American democracy and American antidemocracy was under way.

John Adams read the Pennsylvania constitution and got to work making sure none of its democratical madness infected the new Massachusetts constitution. He succeeded. Massachusetts limited voting rights more strictly than ever before. In 1783 Daniel Shays, a Revolutionary War veteran who had been discharged virtually unpaid, like so many others, returned home to the Berkshires to face the same abuse by the creditor class that had marked life in Massachusetts for generations. When Shays’ Rebellion rose up against crushing new state taxes, earmarked for paying both the interest and the principal on bonds held by that same class, it was Samuel Adams himself who called for the death penalty for the rebels. The lines had been drawn.

In 1787 in Philadelphia, the delegates responded to Edmund Randolph’s exhortation to face and eliminate “the chief danger,” democracy. It was a given, as Alexander Hamilton put it in a note to himself during the convention, that “we need to be rescued from the democracy”; the question under debate, Hamilton scribbled, was “what the means proposed?” John Adams was representing the United States in England that summer, but his spirit hovered over the convention. As early as 1775, Richard Henry Lee of Virginia had asked him for advice on forming a state constitution, and the famous “Virginia Plan” for national government—drafted by Madison, presented at the convention by Randolph, and endorsed tacitly by Washington—was influenced by Adams’ ideas for obstructing democracy. Adams’ hand can be seen especially clearly in Madison’s bicameral legislature, with a small upper house, not representative of the people, to check effects of representation in the lower house, and in the judiciary, appointed for life independently of both the legislature and the public.

Yet the Virginia Plan went even further in its effort to wield national power to squelch democratic leanings and susceptibilities in state legislatures. Madison wanted to give Congress power to veto state laws. That idea didn’t survive debate, but objections to it focused exclusively on intrusions on state sovereignty. Nobody at the convention was defending the democracy movement’s demands for labor-friendly finance policies and debt cancellation or its recalcitrance in paying taxes earmarked for bondholders. Certain elements of the Virginia Plan were overruled in debate—to favor even closer alignment with Adams’ antidemocratic views. Madison had proposed, like Paine, an executive branch elected by the legislature; the final document made the executive a single person with a lot of power, elected independently of the legislature. While the new national government, unlike Massachusetts, didn’t specify property qualifications for voting or holding office—the document didn’t contemplate any right to vote at all—most of the framers expected the majority of states to maintain such qualifications. And with the Electoral College for presidential elections, they placed an additional buffer between the popular vote and selection of the president.

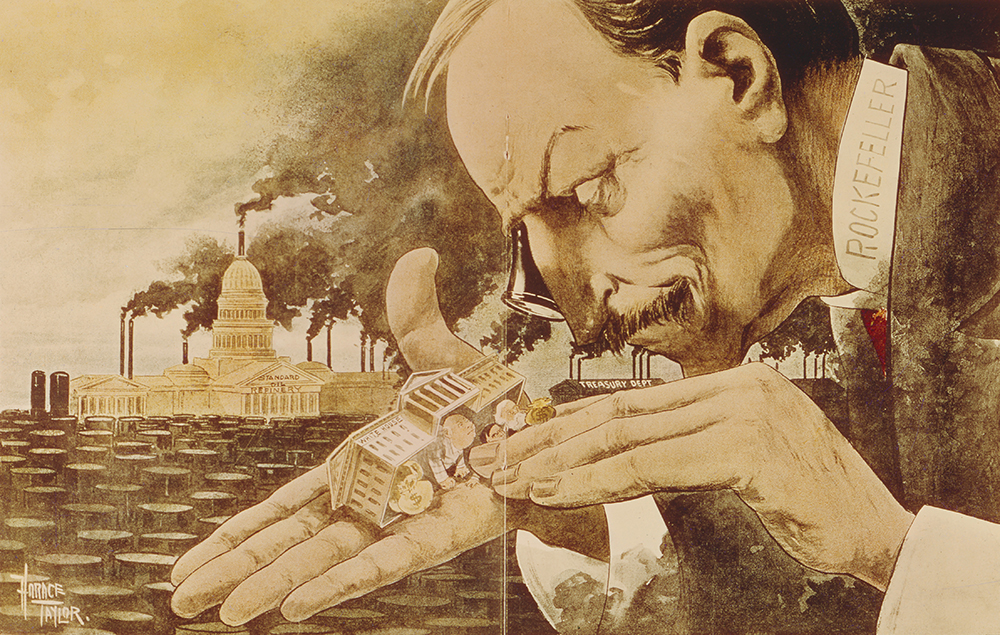

Crucially, the document disabled the threat to the investing class presented by democratic approaches to public and private finance. The states would no longer be able to mint those depreciating paper currencies or make anything but gold and silver a legal tender, and the new U.S. Congress was empowered to tax the citizenry, on a countrywide basis, for the benefit of holders of war bonds and to enforce its taxes by taking over and calling out the states’ militias. These provisions, intended to protect big lending and high finance and rarely noted today, were of paramount importance to the framers. Madison’s Federalist 10 celebrates the power in the document to stifle “a rage for paper money, for an abolition of debts, for an equal division of property, or for any other improper or wicked project.” In an unpublished essay of 1787, Hamilton notes that the national government will “restrain the means of cheating creditors.” During the ratification debates, Washington wrote to Madison to say that while he might be able to live with certain amendments, if the national taxing power in support of the bondholders’ interest payments were removed from the document, the entire constitutional project would be rendered meaningless. The Constitution framed in Philadelphia thus brought an enormous, new, and well-consolidated interstate force against American democracy.

The Trust Giant’s Point of View, by Horace Taylor, 1900. Snark / Art Resource, NY.

In response to that stunning blow, some leaders of the democratic movement joined with elite state-sovereignty advocates, known as anti-federalists, to obstruct ratification. The failure of their effort to stop the Constitution ushered some, ironically, into the new national government they’d opposed. They became members of a political opposition party, the Jeffersonian Republicans. That party did espouse more democratic ideas than the Federalists. Yet commitments to state sovereignty and white supremacy made the Republican constitutional philosophy a far cry from the nationally organized, egalitarian, abolitionist welfare state espoused by Husband and Paine.

Husband and Paine themselves didn’t do so well. By 1789 Paine was in England, promoting reason, democracy, and working-class rights and dodging arrest for sedition. As a hero of Liberté, egalité, fraternité, he was a member of the government of revolutionary France; soon after that he was a prisoner of the Terror, arrested as a counterrevolutionary for objecting to beheading the king and queen. He demanded release, claiming American citizenship. But the Washington administration, fed up with Paine’s international efforts for democracy, no longer wanted to claim him, and the author of Common Sense was left to die. He avoided the guillotine by sheer luck and was released in 1794, thanks to the efforts of the new U.S. minister to France, James Monroe. Paine came back to the United States but was never the same. He died in 1809. Six people came to his funeral, none of them comrades from 1776.

Herman Husband, out of the Pennsylvania assembly and back home in the mountains by 1787, had high hopes for the U.S. Constitution. When he read it, he was as horrified as John Adams had been by Pennsylvania’s constitution. Husband saw the document’s purport: to demolish hope for American democracy. Crushed and infuriated by the betrayal, he exhorted his western Pennsylvania neighbors to rise up against the first federal tax, passed in 1791. This was an excise on whiskey, earmarked to pay the bond-holding class its tax-free 6 percent interest by collecting funds from the many who held no bonds. Devised by the first Treasury secretary, Alexander Hamilton, the law taxed big industrial whiskey producers only fractions of what the poorest seasonal producers paid. It enabled big producers to monopolize the most important whiskey market, U.S. Army supply, driving small producers out of business. It favored the East over the West. It appointed federal government cronies, sometimes the big whiskey producers themselves, to collect the tax from their poorer neighbors for a cut.

After all of the sacrifices that ordinary people had made in the War of Independence in hopes of ending government on behalf of the rich, Husband, now in his seventies, found his commitment to nonviolence wavering. The free people, he preached, citing scripture, were many, their oppressors few. The ensuing Whiskey Rebellion had familiar features: black-faced gangs in freakish costume, attacks on federal officials, even shoot-outs. At first the rebels’ demand was for equal taxation. Soon, though, they were planning armed secession of the whole region and the establishment of a more egalitarian society. President Washington carried out a military suppression of western Pennsylvania, using state militias now federalized under the Constitution. Herman Husband was arrested, marched over the mountains in the snow and all the way to Philadelphia, thrown in the city jail, and charged with sedition. He was acquitted but had caught pneumonia in prison; he died on his way home.

So democracy was present at the founding, indeed crucial to it—and then it wasn’t. Democratic institutions came to the United States not via the founders’ Constitution, designed to suppress democracy, and not via the visions of Paine and Husband, which the Constitution suppressed, but in unexpected ways that still tangle our politics. The states removed electoral property qualifications for white men, but voting by women and free blacks was even further restricted. The Jackson era’s democratic moods and gestures were associated with removal of indigenous people and militant defense of slavery. The Civil War emancipated the enslaved, yet the failure of the Freedmen’s Bank robbed the emancipated of generations of future wealth. The post–Civil War amendments gave federal protection to equal voting rights not only for black men but also, for the first time, for white men—while constitutionally acquiescing for the first time in disenfranchising women. Voting equality remained a dead letter in the South for a century, fostering the system of violence known as Jim Crow. The Indian Citizenship Act at once enfranchised Native Americans and undermined their tribal sovereignty. Benefits of egalitarian New Deal relief and service programs were reaped by white citizens at the expense of black citizens.

It’s also true that first-wave feminism fought for and gained women the right to vote. The civil rights movement fought off the consignment of black Americans to violence and powerlessness. Successive ongoing movements have fought for equal rights for women, for LGBTQ people, for citizens of color, for poor people. These gains for democracy, never complete, are under constant threat. That peril may be related to our difficulty in seeing the founders’ Constitution the way the founders saw it: as a sharp check on democracy. To locate genuinely democratic impulses in the founding generation, we should look not to our founders but to Shays, Young, Cannon, Paine, Husband, and others, and at the many people they led. We may find much to admire in the founding-era democratic movement, and much that seems not only dismayingly partial—many of the activists weren’t better than their elite opponents regarding rights for people other than white men—but also dangerous: Paine in France, Husband with the whiskey rebels, the populist vigilantism that has found outlets not only in democratic but also in authoritarian movements. The story of the most persistent and unrelenting of those democratic leaders, Paine and Husband, ends sadly, even tragically.

Still, American democracy has ancestors. Remembering their strengths and failings—and leaving the founders alone—might help us know, keep, and grow what we have of democracy now.

This essay appears in Democracy, the Fall 2020 issue of Lapham’s Quarterly. The issue is made possible by a generous grant from the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation.