Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.

—Ludwig Wittgenstein, 1921Horsepower

The thrilling history of the Pony Express.

In the spring of 1860, Bolivar Roberts, superintendent of the western division of the Pony Express, went to Carson City, Nevada, to engage riders and station agents for the Pony Express route across the Great Plains.

In a few days, fifty or sixty riders were engaged—men noted for their lithe, wiry physiques, bravery and coolness in moments of great personal danger, and endurance under the most trying circumstances of fatigue. Particularly were these requirements necessary in those who were to ride over the lonely route. It was no easy duty; horse and human flesh were strained to the limit of physical tension. Day or night, in sunshine or in storm, under the darkest skies, in the pale moonlight, and with only the stars at times to guide him, the brave rider must speed on. Rain, hail, snow, or sleet, there was no delay; his precious burden of letters demanded his best efforts under the stern necessities of the hazardous service; it brooked no detention; on he must ride. Sometimes his pathway led across level prairies, straight as the flight of an arrow. It was oftener a zigzag trail hugging the brink of awful precipices and dark, narrow canyons infested with watchful savages, eager for the scalp of the daring man who had the temerity to enter their mountain fastnesses.

At the stations the rider must be ever ready for emergencies; frequently double duty was assigned him. Perhaps he whom he was to relieve had been murdered by the Indians, or so badly wounded that it was impossible for him to take his tour; then the already tired expressman must take his place and be off like a shot, although he had been in the saddle for hours.

The ponies employed in the service were splendid specimens of speed and endurance; they were fed and housed with the greatest care, for their mettle must never fail the test to which it was put. Ten miles distance at the limit of the animal’s pace was exacted from him, and he came dashing into the station flecked with foam, nostrils dilated, and every hair reeking with perspiration, while his flanks thumped at every breath.

Nearly two thousand miles in eight days must be made; there was no idling for man or beast. When the Express rode up to the station, both rider and pony were always ready. The only delay was a second or two as the saddle pouch with its precious burden was thrown on and the rider leaped into his place, then away they rushed down the trail, and in a moment were out of sight.

Two hundred and fifty miles a day was the distance traveled by the Pony Express, and it may be assured the rider carried no surplus weight. Neither he nor his pony were handicapped with anything that was not absolutely necessary. Even his case of precious letters made a bundle no larger than an ordinary writing tablet, but there was five dollars paid in advance for every letter transported across the continent. Their bulk was not in the least commensurable with their number; there were hundreds of them sometimes, for they were written on the thinnest tissue paper to be procured. There were no silly love missives among them nor frivolous correspondence of any kind; business letters only that demanded the most rapid transit possible and warranted the immense expense attending their journey found their way by the Pony Express.

The Pony Express, as a means of communication between the two remote coasts, was largely employed by the government, merchants, and traders, and would eventually have been a paying venture had not the construction of the telegraph across the continent usurped its usefulness.

The arms of the Pony Express rider, in order to keep the weight at a minimum, were, as a rule, limited to revolver and knife.

The first trip from St. Joseph to San Francisco, 1,966 in exact miles, was made in ten days; the second, in fourteen; the third, and many succeeding trips, in nine. The riders had a division of from one hundred to 140 miles, with relays of horses at distances varying from twenty to twenty-five miles.

In 1860, the Pony Express made one trip from St. Joseph to Denver, 625 miles, in two days and twenty-one hours.

The Pony Express riders received from $120 to $125 a month. But few men can appreciate the danger and excitement to which those daring and plucky men were subjected; it can never be told in all its constant variety. They were men remarkable for their lightness of weight and energy. Their duty demanded the most consummate vigilance and agility. Many among their number were skillful guides, scouts, and couriers, and had passed eventful lives on the Great Plains and in the Rocky Mountains. They possessed strong wills and a determination that nothing in the ordinary course could balk. Their horses were generally half-breed California mustangs, as quick and full of endurance as their riders, and were as surefooted and fleet as a mountain goat; the facility and pace at which they traveled was a marvel. The Pony Express stations were scattered over a wild, desolate stretch of country two thousand miles long. The trail was infested with “road agents” and hostile savages who roamed in formidable bands, ready to murder and scalp with as little compunction as they would kill a buffalo.

Some portions of the dangerous route had to be covered at the astounding pace of twenty-five miles an hour, as the distance between stations was determined by the physical character of the region.

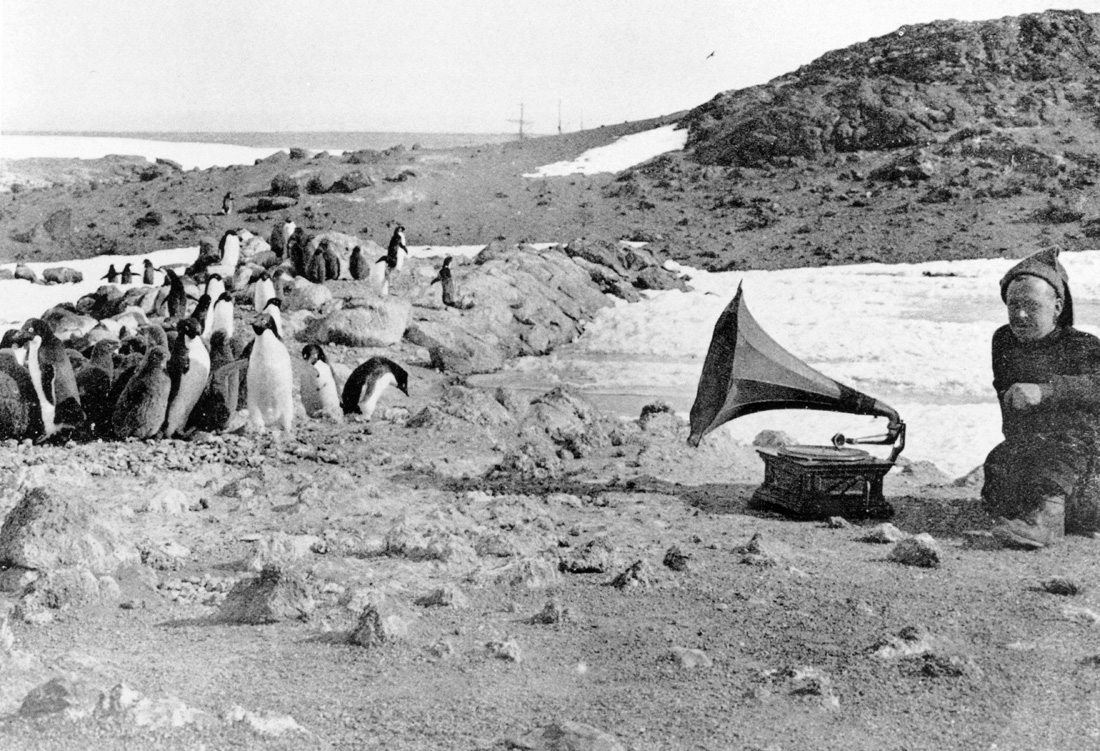

Penguins listening to a gramophone during Ernest Shackleton’s expedition to Anartica, 1907. The Bridgeman Art Library.

The Civil War began nine months after the Pony Express was started, and never has news been more anxiously awaited than on the Pacific Coast during the existence of this enterprise. The first tidings of the attack on Fort Sumter were sent by the Pony Express, and its connections, to San Francisco in eight days, fourteen hours. From that time on, a bonus was given by California businessmen and public officials to the Pony Express Company to be distributed among the riders for carrying war news as fast as possible. For bringing the news of the Battle of Antietam to Sacramento one day earlier than usual, in 1861, a purse of three hundred dollars extra was collected for the riders.

During the last few weeks preceding the termination of the Pony Express, by the opening of the transcontinental telegraph, the express riders brought an average of seven hundred letters per week from the Pacific Coast. In those last few weeks, after the telegraph had been completed to Fort Kearney, the “pony” rates were reduced to one dollar per half ounce, and each letter was enclosed in a ten-cent government-stamped envelope for each half ounce, and this was the only financial interest the government had, at any time, in the Pony Express enterprise, until the remnant of it was transferred by Russell, Majors & Waddell to the Wells-Fargo Company.

In all the trips across the continent, and the 650,000 miles ridden by the Pony Express riders of the Russell, Majors & Waddell Company, the record is that only one mail was lost, and that a comparatively small and unimportant one.

William Lightfoot Visscher

From A Thrilling and Truthful History of the Pony Express. A prolific poet, peripatetic journalist, and novelist, Visscher published his account in 1908, more than forty-five years after the service’s termination following the advent of the transcontinental telegraph system. An efficient method of transport but a financially untenable enterprise, the Express was in operation for a total of eighteen months.