We never are definitely right; we can only be sure we are wrong.

—Richard P. Feynman, 1965A Hideous and Desolate Wilderness

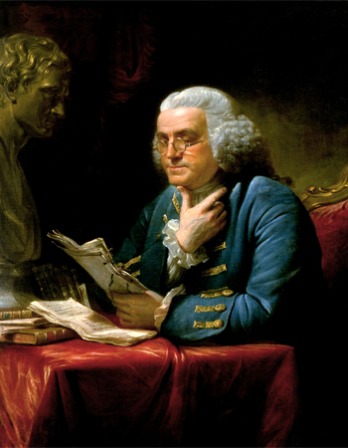

Colonists survey their new home.

After long beating at sea they fell with that land which is called Cape Cod; the which being made & certainly known to be it, they were not a little joyful.

After some deliberation had amongst themselves & with the master of the ship, they tacked about and resolved to stand for the southward (the wind & weather being fair) to find some place about Hudson’s river for their habitation. But after they had sailed that course about half the day, they fell amongst dangerous shoals and roaring breakers, and they were so far intangled there with as they conceived themselves in greater danger; & the wind shrinking upon them withall, they resolved to bear up again for the Cape, and thought themselves happy to get out of those dangers before night overtook them, as by God’s providence they did. And the next day they got into the Cape harbor where they rode in safety.

Being thus arrived in a good harbor and brought safe to land, they fell upon their knees & blessed the God of heaven, who had brought them over the vast & furious ocean, and delivered them from all the perils & miseries thereof, again to set their feet on the firm and stable earth, their proper element. Being thus past the vast ocean, and a sea of troubles before in their preparation (as may be remembered by that which went before), they had now no friends to welcome them, nor inns to entertain or refresh their weather-beaten bodies, no houses or much less towns to repair to, to seek for succor. It is recorded in scripture as a mercy to the apostle & his shipwrecked company, that the barbarians showed them no small kindness in refreshing them, but these savage barbarians, when they met with them were readier to fill their sides full of arrows then otherwise. And for the season it was winter, and they that know the winters of that country know them to be sharp & violent & subject to cruel & fierce storms, dangerous to travel to known places, much more to search an unknown coast. Besides, what could they see but a hideous & desolate wilderness, full of wild beasts & wild men? And what multitudes there might be of them they knew not. Neither could they, as it were, go up to the top of Pisgah, to view from this wilderness a more goodly country to feed their hopes; for which way soever they turned their eyes (save upward to the heavens) they could have little solace or content in respect of any outward objects. For summer being done, all things stand upon them with a weather-beaten face; and the whole country, full of woods & thickets, represented a wild & savage hue. If they looked behind them, there was the mighty ocean which they had passed, and was now as a main bar & gulf to separate them from all the civil parts of the world. What could now sustain them but the spirit of God & His grace? May not & ought not the children of these fathers, rightly say: Our fathers were Englishmen which came over this great ocean, and were ready to perish in this wilderness.

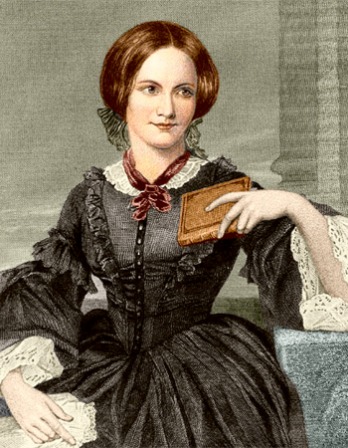

William Bradford

From History of Plymouth Plantation. An organizer of the exodus of one hundred-odd Pilgrims from England and Holland, and a framer of the social compact signed aboard the Mayflower, Bradford was elected governor of the Plymouth Colony in 1621. Reelected to the office thirty times before he died in 1657, he kept journals from 1620 to 1647 that form the definitive account of the American pilgrimage.