Alas! We are ridiculous animals.

—Horace Walpole, 1777On Patrol with the K-9 Unit

Burkhard Bilger explores the history of police dogs.

The New York City subway has more than four hundred stations, eight hundred miles of track, six thousand cars, and, on any given weekday, five million passengers. It’s an antiterrorism unit’s nightmare. To sweep this teeming labyrinth for bombs would take an army of explosives experts equipped with chemical detectors. Instead, the city has gone to the dogs. Since 2001, the number of uniformed police has dropped by 17 percent. In that same period, the canine force has nearly doubled. It now has around a hundred dogs, divided among the narcotics, bomb, emergency-response, and transit squads.

A good dog is a natural supersoldier: strong yet acrobatic, fierce yet obedient. It can leap higher than most men and run twice as fast. Its eyes are equipped for night vision, its ears for supersonic hearing, its mouth for subduing the most fractious prey. But its true glory is its nose. In the 1970s, researchers found that dogs could detect even a few particles per million of a substance; in the 1990s, more subtle instruments lowered the threshold to particles per billion; the most recent tests have brought it down to particles per trillion. “It’s a little disheartening, really,” Paul Waggoner, a behavioral scientist at the Canine Detection Research Institute, at Auburn University, in Alabama, told me. “I spent a good six years of my life chasing this idea, only to find that it was all about the limitations of my equipment.”

Just as astonishing, to Waggoner, is a dog’s acuity—the way it can isolate and identify compounds within a scent, like the spices in a soup. Drug smugglers often try to mask the smell of their shipments by packaging them with coffee beans, air fresheners, or sheets of fabric softener. To see if this can fool a dog, Waggoner has flooded his laboratory with different scents, then added minute quantities of heroin or cocaine to the mix. In one case, “the whole damn lab smelled like a Starbucks,” he told me, but the dogs had no trouble homing in on the drug. “They’re just incredible at finding the needle in the haystack.”

The New York police have two kinds of canines: detection dogs and patrol dogs. The former spend most of their time chasing down imaginary threats: terrorist attacks are so rare that the police have to stage simulations, with real explosives, to keep the dogs on their toes. Patrol dogs, on the other hand, have one of the most dangerous jobs in public life. Canine police are often called when a criminal is on the loose, and they’re far more likely than others to have a lethal encounter. “The crimes I get called out on are always in progress,” one officer told me. “The suspects are armed. They’re known to be violent. So, by the mere nature of that call, it’s going to be more dangerous.” He shrugged. “I guess I’m an adrenaline junkie. I got into canines to hunt men.”

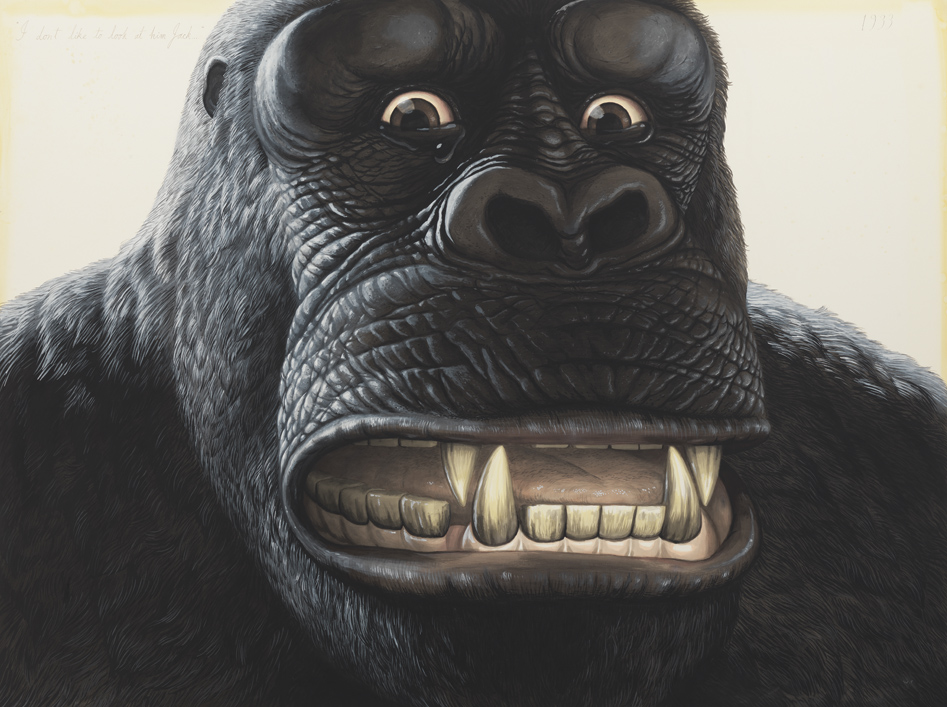

I Don’t Like to Look at Him, Jack, by Walton Ford, 2011. Watercolor, gouache, ink, and pencil on paper, mounted on aluminum panel. © Walton Ford, courtesy of the artist and Paul Kasmin Gallery.

The dogs in the Long Island City training facility are heirs to an ancient and bloodthirsty line. Their ancestors, descended from the great mastiffs and sighthounds of Mesopotamia, were used as shock troops by the Assyrians, the Persians, the Babylonians, and the Greeks. (Alexander the Great’s dog, Peritas, is said to have saved his life at Gaugamela by leaping in front of a Persian elephant and biting its lip.) They wrought havoc in the Roman Colosseum, ran with Attila’s hordes, and wore battle armor beside the knights of the Middle Ages. In 1495, when Columbus sailed to what is now the Dominican Republic, he brought Spanish mastiffs almost three feet high at the withers and greyhounds that could run down an enemy and disembowel him.

The German shepherd, first registered as a breed in 1889 by a former cavalry captain, Max von Stephanitz, was selected for intelligence and steadiness as well as power. The Germans fielded thirty thousand dogs in World War I, and used them for everything from transporting medicine and wounded soldiers to shuttling messages between trenches. When the war was over, the animals were mostly killed, discarded, or consumed by the starving populace. “Dog meat has been eaten in every major German crisis at least since the time of Frederick the Great, and is commonly referred to as ‘blockade mutton,’” Time noted in 1940. “Dachshund is considered the most succulent.”

The survivors went on to second careers in law enforcement or as guide dogs for the blind, and their breeding and training grew ever more sophisticated. In Germany, registered shepherds have to pass rigorous physical and behavioral tests, and their puppies are trained by nationwide networks of volunteers. Schutzhund competitions, in which dogs are tested for their ability to track, obey orders, and protect their owners, are a national passion, and the largest ones fill stadiums. “They just have a different dog culture over there,” Steve White, a dog trainer and former canine officer in the Seattle area, told me. “If you look at North America, there are maybe five thousand German shepherd breeders. If you go to Germany, it’s probably got fifty-five thousand.”

It took the Lockerbie bombing, followed by the attacks at Columbine and Oklahoma City, to galvanize interest in police and military dogs in America. Auburn University’s canine program began as an attempt to build a better bomb detector. “In the eighties, we thought, Let’s build a machine that can mimic the dog!” Robert Gillette, the director of the university’s animal-health and performance program, told me. “But you can’t mimic a dog. It’s just a superior mechanical working system. So in the nineties we began to think, Hmm, let’s put some of that research into the animals.” The Department of Defense has apparently come to the same conclusion. Since 2006, it has spent close to twenty billion dollars searching for explosives in Iraq and Afghanistan. “The detection rate has hung stubbornly at around 50 percent,” Lieutenant General Michael Oates told the magazine National Defense two years ago. When the same patrols use dogs, he added, the success rate leaps to 80 percent: “Dogs are the best detectors.”

The American military now has some three thousand active-duty dogs in its ranks, but good animals are hard to find. The American Kennel Club requires no proof of health or intelligence to register an animal—just a pure bloodline—and breeders are often more concerned with looks than with ability. “We breed for the almighty dollar here,” one trainer told me. Programs like the ones at Auburn and at Lackland Air Force Base in San Antonio are trying to reverse that trend. But their graduates are still the exceptions. “Some of these dogs, they couldn’t find a pork chop if it was hanging around their neck,” a dog broker in Minnesota told me.

The upshot is that many, if not most, American police dogs now come from Europe. Those in the New York subway were mostly born in Hungary, Slovakia, or the Czech Republic—descendants of the powerful border-patrol dogs bred during the Cold War. Other police dogs come from brokers in the Netherlands and Germany and still respond to Dutch and German commands: Sitz! Bleib! Los! Apport! “Europeans have more dogs than they can use, so they sell the excess to us,” White told me. “We subsidize their hobbies.”

Canine police tend to talk about their dogs as if they were mechanical devices. They describe them as tools or technology and say that they’re “building dogs” through proper training. They say that their animals need “maintenance” to be “fully operational,” and that a “dual-purpose dog”—one that has been taught to both chase down criminals and detect drugs or explosives—has “superior functionality.” At home, a police dog may be like a member of the family. But once in the field it’s just another piece of gear.

This is more than a manner of speaking. It’s a way of thinking about dogs that goes back to the psychologist B. F. Skinner and his work on behaviorism in the 1940s. Skinner argued that it’s pointless to imagine what’s going on in an animal’s head. Better to treat its mind as a black box, closed and unknowable, with inputs that lead to predictable outputs. Skinner identified four ways to manipulate behavior: four buttons to push—positive reinforcement (“Good dog! Have a biscuit”), positive punishment (“Bad dog! Whack”), negative reinforcement (“Good dog! Now I’ll stop whacking you”), and negative punishment (“Bad dog! Give me back that biscuit”). Connect an action to an outcome and almost any behavior can be trained. Skinner called this “operant conditioning” and considered it as effective for people as for their pets. “Give me a child,” he once said, “and I’ll shape him into anything.”

DFB 42, Êléktra Ozomène, by Brandon Ballengée, 2008. Cleared-and-stained multilimbed Pacific tree frog from Aptos, California. In scientific collaboration with Stanley K. Sessions, title by the poet KuyDelair. Unique IRIS print on watercolor paper, 46" x 34". © Brandon Ballengée, courtesy of the artist and Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, New York, New York.

The patrol dogs in the transit squad could bark on command (Speak!) and urinate at their handler’s discretion (Empty!). They could climb ladders, crawl through drainage pipes, and leap through the open window of a moving car. They were smart, disciplined, extremely capable animals. But the blood of the old war-hounds still ran in them, and their most effective ability was intimidation.

“One canine team can do the work of ten or fifteen guys in a gang situation,” Lieutenant John Pappas, the head of the squad, told me. “It’s ‘Fuck you! I’m not going anywhere.’ But when you throw in some jaws and paws—holy shit! It changes the landscape.” In 2010, one station on the Lexington Avenue line was hit by twenty felonies in a matter of months. Once a canine unit was sent in, the number dropped to zero. “It’s like pulling up in an M1 Abrams battle tank,” Pappas said.

© 2012 Burkhard Bilger. Used with permission of Burkhard Bilger.

Burkhard Bilger

From “Beware of the Dogs.” The first city to establish a police-dog training school was Ghent, Belgium, in 1899. About its effect, the New York Times reported in 1902 that “the dog has become a recognized member of the regular town constabulary,” and “crime in that particular district patrolled by him is said to have diminished by two-thirds since his entry into the force.” Bilger published his first book, Noodling for Flatheads: Moonshine, Monster Catfish, and Other Southern Comforts, in 2000 and became a staff writer for The New Yorker in 2001.