A fool’s brain digests philosophy into folly, science into superstition, and art into pedantry. Hence university education.

—George Bernard Shaw, 1903Portraits of the Artist

If today there is no longer any particular set of skills that must be learned in order for one to make art, how does one become an artist?

By Howard Singerman

The Model (Students in the Art Room), by anonymous, c. 1910.

The Weimar Bauhaus was founded in 1919 on the premise that art “cannot be taught and cannot be learned.” Art is not “a profession which can be mastered by study,” wrote Walter Gropius in the school’s first program; rather, it blossoms “in rare moments of inspiration” by “the grace of heaven.” That Gropius launched what would become the most influential art school of the twentieth century on such contradictory grounds underscores the problem implicit in the teaching of art. Gropius was not the first to claim that art cannot be taught, and its corollary, the ideal of the “born artist,” runs long and deep in the current of Western civilization. Pliny the Elder asserted in the first century that the Greek sculptor Lysippus “was no one’s pupil”; Albrecht Dürer, in the sixteenth century, praised the Dutch artist Geertgen tot Sint Jans as “truly a painter in his mother’s womb.” The tradition continues into the present with the art historian Robert Pincus-Witten’s description in the early 1980s of David Salle as a “painter born.” And yet most artists from Lysippus forward have been someone’s pupil; David Salle’s Master of Fine Arts degree is only the latest way that the title of artist is bestowed.

From the early Middle Ages, young artists apprenticed in workshops. Some of them were based in a monastery or a palace, but most belonged to the bottegas [studios] of individual masters. Guilds set the terms of apprenticeship and decided when the students were skilled enough to work as journeymen, and then as masters—professional artists—themselves. Karl van Mander, who recorded Dürer’s tribute to Geertgen, clarified in his 1604 Schilder-Boeck that Geertgen had been a pupil of the painter Albert van Ouwater. Dürer, too, was a pupil, apprenticed for three years to a painter named Michael Wohlgemuth, and before that, to his own father, a goldsmith. Like many artists—most notably the elder and younger Pieter Bruegels and the Hans Holbeins—Dürer was born into a family of artists and skilled craftsmen. His artistic lineage speaks less to the imaginary genetics at play in the womb than to the economics of his family’s business, passing on from generation to generation its recipes, tools, and representational types.

The founding of the first academies in the sixteenth century and their flowering in the seventeenth under state sponsorship proceeded from the idea that there is more to be taught, and more to being an artist, than practical training. Insistent upon the separation of art as a cosa mentale from the manual skills of the workshop, the academies were in fact founded to produce that difference. Bottega apprentices worked for and on a master’s products—grinding paints, preparing grounds, laying in backgrounds or compositions according to existing models or templates. The academy’s students studied the principles of art. “Study first the science, then the practice born of that science,” Leonardo da Vinci advised in a treatise circulated in manuscript that intended to elevate painting above the mechanical arts and to raise the artist above those artisans with whom he had shared his guild membership. Leonardo’s first principles were not manual or material, but rather those of disegno: point, line, surface, and the body enclosed by that line.

The first official academy was Giorgio Vasari’s Accademia del Disegno, founded in Florence in 1563 with the support of the Medicis. Drawing was the core of its teaching. Accompanied by lectures in the new sciences of anatomy and perspective, the posed nude came to define the academy and what was meant by “fine art” for the next three centuries. The French Académie Royale, the strongest and most influential academy in Europe, was founded in 1648 with the exclusive right to pose the nude model, and académie came to mean both the institution and the drawing that was taught there. Two hundred years later, in 1863, when new generations of theorists threatened to bring practical studio classes on painting, sculpture, architecture, and engraving into the Académie’s École des Beaux-Arts, the academician Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres argued that the École “teaches only drawing, but drawing is everything; it is the whole of art. The material processes of painting are very simple, and can be taught in eight hours.”

Chiron and Achilles depicted in a fresco in Herculaneum, Italy, first century. National Archaeological Museum, Naples, Italy.

The battle cry for the reformers of the École des Beaux-Arts was “Utilité!” and the 1863 reforms, however small, were but a part of a broad movement across Europe. Parliamentarians, manufacturers, educators, and myriad writers on the arts all sought to rationalize art education in general, and to make it more responsive to the commercial needs of the state. The establishment of the Gewerbeschulen in Germany and schools of design in England in the 1830s and ’40s were attempts to replace the collapsed guild-based apprenticeship system and adapt to the new conditions of industrial manufacture. These schools eschewed life drawing: students in the British schools early on had to declare that they were not studying to be artists.

The new schools taught a very different kind of drawing—mechanical drawing—to a clientele identified in the title of the main course at London’s Central School of Design at Somerset House as “Designers, Ornamentists, and Those Intending to Be Industrial Artists.” The course employed a regularly stepped syllabus, from repeated drills in straight and curved lines to copies of geometric figures in plane. The student’s principal three-dimensional model was not the nude but “type solids”—cubes, cones, cylinders, spheres—and plaster casts of architectural ornament. By 1880, the Central School of Design’s curricula were in use at forty-seven hundred elementary schools. For the proponents of the schools of design, the academic drawing that Ingres insisted was the “whole of art” was useless: not only for the young industrial artist or factory draftsman, but increasingly for those who would be painters or sculptors. The academy’s concentration on drawing and the human figure came to be seen as meaningless and isolating, a view that cemented the old division between artist and artisan along the class lines of modern industrial society.

It was precisely this division that Gropius intended the Bauhaus to heal. “There is no essential difference between the artist and the craftsman,” he declared in his 1919 manifesto. Dismissing both the old academy model and the new regimented design classroom, he concluded by appealing to the vision of the medieval guild: “There are no teachers and pupils at the Bauhaus, but masters, journeymen, and apprentices.” But Gropius’ apprentices could no longer become twelfth-century stonecutters, and by the time of the Bauhaus’ move to Dessau in 1925, its ideal craftsman was an industrial designer, fashioning objects in metal, glass, and plastic for industrial production. Like Leonardo before him, Gropius insisted on first principles, but his were not those of disegno as figurative representation—a copy of this world made beautiful—but rather of design as the projection of a new world. Those principles were established in the Bauhaus’ famous Vorkurs, the foundation course taught over the years by Johannes Itten, Josef Albers, and László Moholy-Nagy. A comprehensive curriculum organized by materials and procedures followed from that foundation, a technique-based syllabus borrowed from the Gewerbeschulen and a format now standard in American art schools and university art departments.

The Bauhaus closed in 1933, and over the next decade the emigration of many of its most prominent faculty members to the United States helped to transform American art education. Albers started at Black Mountain College in 1933 and was appointed head of the school of design at Yale in 1950; Gropius himself was at Harvard by 1937; Moholy-Nagy founded the New Bauhaus in Chicago that same year. Taken as an exemplar of modern, rational art education, the Bauhaus was singularly influential in the quest to bring the practice of art into colleges and universities in the form of both general education and professional training—premised on Moholy-Nagy’s idea that “any healthy man can become a musician, painter, sculptor, or architect.” The first Master of Fine Arts degree was probably awarded at the University of Washington in 1924, but it was only in the years after World War II that the MFA became a recognizable part of the American university. There are now over two hundred degree-granting graduate studio art programs, the majority established since 1970.

The history of art education from the guild to the university suggests a coherent trajectory: the increasingly formalized training of the artist as a professional. But open to the education pages of Art Digest from September 15, 1948, and there is another side to the story. The four-page spread includes advertisements for over seventy art schools, including academies, ateliers, and studios offering correspondence courses. Among the columns of ads, two now can be seen as historically pertinent. One is an announcement for the newly formed National Association of Schools of Design, an accrediting association founded to align art education with university admissions, degree standards, core requirements, and regularized credit hours. The other is the announcement of a new art school located at 35 East Eighth Street in Greenwich Village, New York City.

The second ad listed four names: Mark Rothko, Robert Motherwell, William Baziotes, and David Hare. Two of those names now read as shorthand for the Abstract Expressionist movement, but all of them would, at the time, have been as unfamiliar as the school’s odd name: Subjects of the Artist. Clyfford Still was involved with the school’s earliest planning, before it received its name, to which he strongly objected. Barnett Newman, who coined the name “to emphasize that abstract art, too, had a subject,” was added to the list of teachers for the school’s second term in January 1949. Tucked between an ad for the Workshop School, which promised “not theoretical instruction, but really practical training and experience,” and one for the Ozenfant School, “the leading school of modern art,” the ad for Subjects of the Artist promised “A New Kind of Art School.”

It’s not clear what its founders meant when they labeled Subjects of the Artist a new kind of art school. Institutionally it looked more like the old-fashioned ateliers in the adjacent advertisements than the university art departments. Stylistically there were other, already established choices available for those interested in modern painting; not only Amédée Ozenfant’s school but also Hans Hofmann’s, presented in an even bigger ad across the page. Hofmann, who eventually taught a whole host of artists who have become household names—among them Lee Krasner, Helen Frankenthaler, and Allan Kaprow—is as important to the development of American art education as the Bauhaus that produced him. He was certainly more important than Subjects of the Artist, which was something of a failure: the school ran for three ten-week terms before closing in May 1949, and had perhaps seventeen regular students.

Still, Subjects of the Artist is worth spending some time with because it marks the emergence of what Clyfford Still once called “the discipline of speaking”—the critiques, conversations, and visiting-artist presentations that now characterize much graduate training. According to the one-page catalogue Robert Motherwell wrote for Subjects of the Artist, there were “no formal courses” and “no technical requirements.” The school’s curriculum was based neither in drawing nor in métier, but in language—as it hovers around a work of art or moves away from it toward broader, more philosophical questions: questions that students had to construe and to answer for themselves. “They changed me completely,” a student later recalled. “Now I had to destroy the object, get rid of horizon, and not use any literary subject either.” What was worked on at Subjects of the Artist—what was taught and formed—was not the work of art (which is, after all, remembered only as what had to be destroyed) but the artist himself. In the words of the painter Robert Goodnough, who, it is worth noting, puts the word curriculum in quotes: “The ‘curriculum’ consisted of the subjects that interest advanced artists”—a teaching that sets itself against the sort of correction that characterized the academy, and one that contradicts the idea of basic principles, whether of Leonardo’s disegno or the Bauhaus’ design.

Rothko quite explicitly rejected the Bauhaus’ order and its foundations, which in a way helps to explain why Subjects of the Artist called itself “A New Art School.” Hired by Brooklyn College’s Bauhaus-inspired design department shortly after Subjects closed in 1949, Rothko, when his contract was not renewed, wrote a letter to the department lambasting the dogmatic utilitarianism of what he had been asked to teach, protesting, “It is only by the circumvention of the real intent of the Bauhaus ideology of the courses in Basic Design, Drawing, Color 1 & 2 that I have been able to lay before my students what really I felt had to be said…I was not brought into this department because I am primarily a teacher or an advertising man or a textile man. I was asked to join the department because I am Mark Rothko and the lifelong integrity and intensity which my work represents.” Rothko’s switch from questions of métier—being defined by craft skill—to the question of artistic identity—of what and how one is an artist—is clear.

Rothko’s complaint sounds like that of a romantic artist—and indeed, it is—but it is also pragmatic. Unequipped with the traditional training an artist might have needed when he was first hired to teach Brooklyn College’s graphic workshop, he enrolled in a printmaking class uptown at the Art Students League to learn what he was supposed to teach. None of the founders of Subjects of the Artist had received the extensive instruction given to Hofmann in the ateliers of Munich and Paris. In public statements and comments to their students they denied its value. About a year before Subjects opened, Rothko insisted in an interview that he was a self-taught artist, which was only a slight exaggeration. His institutional training amounted to eight months at the Art Students League between 1924 and 1926: two months studying anatomy with George Bridgeman, the remaining six painting still lifes with Max Weber. His two years as a liberal arts student at Yale in the early 1920s encompassed neither studio art nor art history.

Robert Motherwell’s art school instruction was even spottier. He did not spend a full year at either the Otis Art Institute in 1926, at age eleven, or the California School of Fine Arts in 1932. He attempted Stanford’s art department as an undergraduate in the early thirties, but, according to the art historian H. H. Arnason, “he was told by one instructor that his work was ‘too blunt and coarse.’…Nevertheless, he is grateful to that same instructor for advising him to read Proust.” Motherwell graduated from Stanford in philosophy and pursued a graduate degree in philosophy at Harvard before leaving to study art history at Columbia with Meyer Schapiro. Like Rothko, Motherwell became a relatively regular art student only after he became a teacher. He began to paint daily only after a family friend helped him secure a one-year teaching position at the University of Oregon in 1939.

In contrast to Motherwell, Rothko, and the sculptor David Hare, all of whom had first attended university to pursue a career other than art, William Baziotes, the last of Subjects of the Artist’s first-term teachers, had a traditional and formal art education. He attended the venerable National Academy of Design from 1933 to 1936, where he studied anatomy and drew after casts, after the masters, and after the model. But in the context of the Subjects of the Artist, Baziotes’ academic training can be read among the other biographies as simply another way: another example of not knowing how to go about becoming an artist.

Barnett Newman, also in the Subjects faculty, studied on and off at the Art Students League like many would-be artists in New York City in the 1920s and 1930s, and he did so for a good deal longer than Rothko. He attended classes while still a high school student from 1922 to 1926 and returned in 1929 after graduating in philosophy from City College. None of Newman’s paintings and few of his drawings from the period survive; in the early 1940s, he destroyed as much of his earlier work as he could locate. It was as though he was attempting to start from scratch as an artist without a school. A critic once described those early efforts as “all-thumbs drawings,” a description that along with Motherwell’s “blunt and coarse” style suggests that at some point not drawing—not only not being schooled but not being able to be schooled—was part of the promise of Subjects of the Artist. Hare recalls that Newman would assure his Subjects of the Artist students, “I can’t draw at all.”

It’s a handicap—a drawback, so to speak—reflected in Newman’s teaching as well as in the Subjects’ curriculum. “Unlike a truly professional teacher such as Hans Hofmann,” Hare recounts, Newman “never drew or painted on a student’s work to correct it. Newman was content to talk about art in a general theoretical way.” Hofmann was infamous for graphically correcting student work—a leftover, perhaps, of a long tradition formalized in the nineteenth-century French atelier as the séance de correction, a term referring both to the master’s weekly visit and his intervention on student’s drawing. In contrast to Hofmann, and to the nineteenth-century master, what the Subjects of the Artist faculty did was talk. Rothko “could talk endlessly and very brilliantly and poetically and metaphorically and mysteriously,” recalled one of his students.

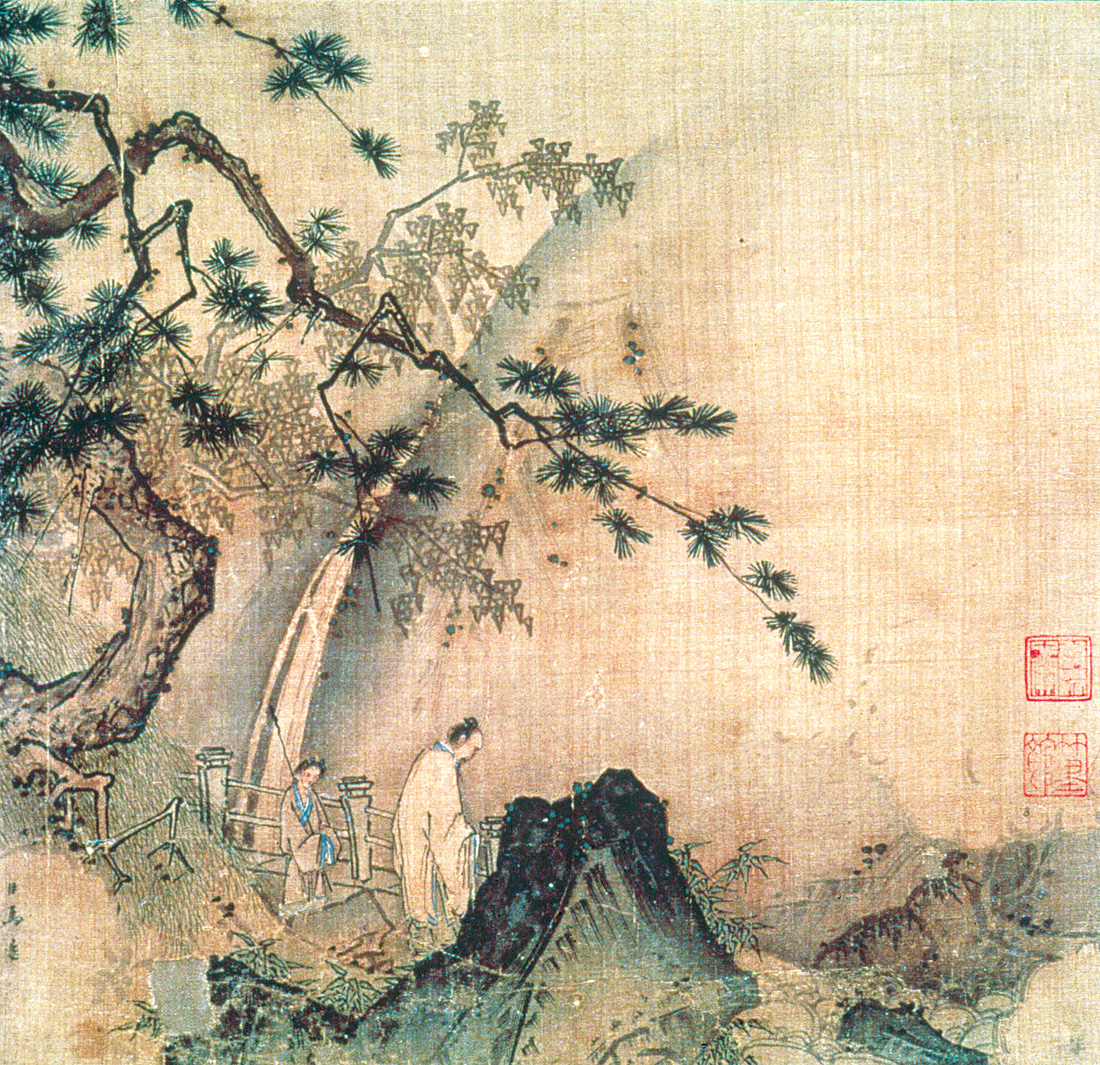

Scholar by a Waterfall, by Ma Yuan, c. 1190–1225. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, C. C. Wang Family, Gift of The Dillon Fund, 1973.

In March 1949, two months before Subjects was to close, Motherwell described the school and its program to the annual Conference of the Committee on Art Education. “The way to learn to paint—to begin one’s orientation, I mean—is to hang around artists. We have made a place where young people can do so…We talk to students as we do to one another.” Subjects of the Artist was first and foremost a place to be with artists, to talk with them, to see what they are like—and to see if you are like them. Learning to become an artist was not the same as learning to make art, or learning the skills of representation. At Subjects of the Artist, the student came to learn if he or she was an artist. Motherwell also stressed the conjunction of talk and proximity, and the value of milieu in the school’s catalogue. “Those who are in the learning stage benefit most by associating with working artists,” for it is only through that association that they can learn “what his subjects are, how they are arrived at, methods of inspiration and transformation, moral attitudes, possibilities for further explorations…”

This, too, is a kind of apprenticeship. Like Gropius, but to very different ends, Motherwell questioned the traditional identifications of teacher and pupil, putting scare quotes around students, as Goodnough had around curriculum: “Those attending the classes will not be treated as ‘students’ in the conventional manner, but as collaborators with the artists in the investigation of the artistic process, its modern conditions, possibilities, and extreme nature, through discussions and practice.” His promise that students would be treated as artistic collaborators is now commonplace. When the California Institute of the Arts opened in 1970, it did not put off the question of being an artist until after graduation; its initial catalogue pledged that “from the day he enters, the student is an artist.” The question was no longer one of practice, but of being: of being an artist in the eyes of one’s teachers, and in the mirror. By the time the Los Angeles sculptor Charles Ray repeated the argument in an article for Spin magazine on the art school boom of the late 1990s, the distinction between being and becoming a professional had collapsed: “Most art schools are about students and teachers. UCLA is about artists working as artists…The reason the kids here are getting all this early success is because they’re not art students, they’re young artists. Young artists get galleries. Students study.”

Ray sounds flippant, but he’s not wrong. It’s not that our art schools have nothing to teach young students, but rather that there is no particular thing that needs to be learned. There is no longer any particular set of skills that must be taught in order for art—at least as we have thought of it for the past century—to be made. And if artists are not defined by their talents or licensed by their skills, then perhaps it does come down, as Subjects of the Artist insisted it does, to a question of being around them. Or as Harold Rosenberg suggested in his canonical 1952 essay “The American Action Painters,” a piece that tried to describe the concerns and the studio talk of artists like those on the faculty at Subjects, it might be a matter of acting out the identity of the artist: “What gives the canvas its meaning is not psychological data but rôle…” An artist need only act as an artist to become one—which is a far more difficult proposition than it sounds when it is no longer clear what an artist is, and maybe even more difficult than learning how to draw.