Technology feeds on itself. Technology makes more technology possible.

—Alvin Toffler, 1970Means of Production

Henry Ford builds an assembly line.

If a device would save in time just 10 percent or increase results 10 percent, then its absence is always a 10 percent tax. If the time of a person is worth fifty cents an hour, a 10 percent saving is worth five cents an hour.

If the owner of a skyscraper could increase his income 10 percent, he would willingly pay half the increase just to know how. The reason why he owns a skyscraper is that science has proved that certain materials, used in a given way, can save space and increase rental incomes. A building thirty stories high needs no more ground space than one five stories high. Getting along with the old-style architecture costs the five-story man the income of twenty-five floors. Save ten steps a day for each of twelve thousand employees, and you will have saved fifty miles of wasted motion and misspent energy.

Those are the principles on which the production of my automobile plant was built up. They all come practically as a matter of course. In the beginning we tried to get machinists. As the necessity for production increased, it became apparent not only that enough machinists were not to be had but also that skilled men were not necessary in production, and out of this grew a principle that I want to present in full.

It is self-evident that a majority of the people in the world are not mentally—even if they are physically—capable of making a good living. That is, they are not capable of furnishing with their own hands a sufficient quantity of the goods this world needs to be able to exchange their unaided product for the goods they need. I have heard it said, in fact I believe it is quite a current thought, that we have taken skill out of work. We have not. We have put in skill. We have put a higher skill into planning, management, and tool building, and the results of that skill are enjoyed by the man who is not skilled.

We have to recognize the unevenness in human mental equipments. If every job in our place required skill, the place would never have existed. Sufficiently skilled men to the number needed could not have been trained in a hundred years. While today we have skilled mechanics in plenty, they do not produce automobiles—they make it easy for others to produce them. Our skilled men are the toolmakers, the experimental workmen, the machinists, and the pattern makers. They are as good as any men in the world—so good, indeed, that they should not be wasted in doing that which the machines they contrive can do better. The rank and file of men come to us unskilled; they learn their jobs within a few hours or a few days. If they do not learn within that time, they will never be of any use to us. These men are, many of them, foreigners, and all that is required before they are taken on is that they should be potentially able to do enough work to pay the overhead charges on the floor space they occupy. They do not have to be able-bodied men. We have jobs that require great physical strength—although they are rapidly lessening; we have other jobs that require no strength whatsoever—jobs that, as far as strength is concerned, might be attended to by a child of three.

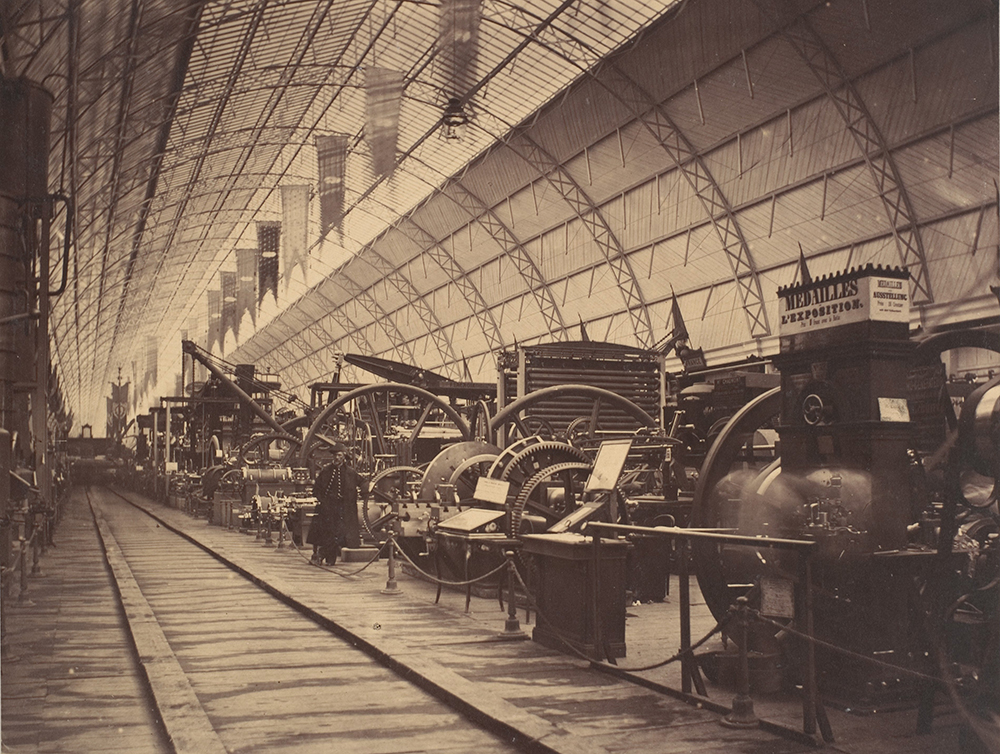

Palace of Industry at the Universal Exposition, Paris, 1855. Photograph by Charles Thurston Thompson. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, purchase, Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation Gift, through Joyce and Robert Menschel, 1992.

A Ford car contains about five thousand parts—that is counting screws, nuts, and all. Some of the parts are fairly bulky, and others are almost the size of watch parts. In our first assembling, we simply started to put a car together at a spot on the floor, and workmen brought to it the parts as they were needed in exactly the same way that one builds a house. When we started to make parts, it was natural to create a single department of the factory to make that part, but usually one workman performed all of the operations necessary on a small part. The rapid press of production made it necessary to devise plans of production that would avoid having the workers falling over one another. The undirected worker spends more of his time walking about for materials and tools than he does in working; he gets small pay because pedestrianism is not a highly paid line.

The first step forward in assembly came when we began taking the work to the men instead of the men to the work. We now have two general principles in all operations—that a man shall never have to take more than one step if possibly it can be avoided, and that no man need ever stoop over.

The principles of assembly are these:

(1) Place the tools and the men in the sequence of the operation so that each component part shall travel the least possible distance while in the process of finishing.

(2) Use work slides or some other form of carrier so that when a workman completes his operation, he drops the part always in the same place—which place must always be the most convenient place to his hand—and if possible have gravity carry the part to the next workman.

(3) Use sliding assembling lines by which the parts to be assembled are delivered at convenient distances.

The net result of the application of these principles is the reduction of the necessity for thought on the part of the worker and the reduction of his movements to a minimum. He does as nearly as possible only one thing with only one movement.

Along about April 1, 1913, we first tried the experiment of an assembly line. We tried it on assembling the flywheel magneto. I believe that this was the first moving line ever installed. The idea came in a general way from the overhead trolley that the Chicago packers use in dressing beef. We had previously assembled the flywheel magneto in the usual method. With one workman doing a complete job, he could turn out from thirty-five to forty pieces in a nine-hour day, or about twenty minutes to an assembly. What he did alone was then spread into twenty-nine operations; that cut down the assembly time to thirteen minutes, ten seconds. Then we raised the height of the line eight inches—this was in 1914—and cut the time to seven minutes. Further experimenting with the speed that the work should move at cut the time down to five minutes. In short, the result is this: by the aid of scientific study, one man is now able to do somewhat more than four did only a comparatively few years ago. That line established the efficiency of the method, and we now use it everywhere.

Sandal Maker, Tomb of Rekhmire, tempera facsimile by Nina de Garis Davies after a c. 1500 bc Egyptian tomb painting, 1931. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1931.

In the chassis assembling are forty-five separate operations or stations. The first men fasten four mudguard brackets to the chassis frame, the motor arrives on the tenth operation, and so on in detail. Some men do only one or two small operations; others do more. The man who places a part does not fasten it—the part may not be fully in place until after several operations later. The man who puts in a bolt does not put on the nut; the man who puts on the nut does not tighten it. On operation number thirty-four, the budding motor gets its gasoline; it has previously received lubrication; on operation number forty-four, the radiator is filled with water, and on operation number forty-five, the car drives out onto John R. Street.

Repetitive labor—the doing of one thing over and over again and always in the same way—is a terrifying prospect to a certain kind of mind. It is terrifying to me. I could not possibly do the same thing day in and day out, but to other minds, perhaps I might say to the majority of minds, repetitive operations hold no terrors. In fact, to some types of mind, thought is absolutely appalling. To them the ideal job is one where the creative instinct need not be expressed. The jobs where it is necessary to put in mind as well as muscle have very few takers—we always need men who like a job because it is difficult. The average worker, I am sorry to say, wants a job in which he does not have to put forth much physical exertion—above all, he wants a job in which he does not have to think. Those who have what might be called the creative type of mind and who thoroughly abhor monotony are apt to imagine that all other minds are similarly restless and therefore to extend quite unwanted sympathy to the laboring man who day in and day out performs almost exactly the same operation.

If a man cannot earn his keep without the aid of machinery, is it benefiting him to withhold that machinery because attendance upon it may be monotonous? And let him starve? Or is it better to put him in the way of a good living? Is a man the happier for starving? If he is the happier for using a machine to less than its capacity, is he happier for producing less than he might and consequently getting less than his share of the world’s goods in exchange?

I have not been able to discover that repetitive labor injures a man in any way. I have been told by parlor experts that repetitive labor is soul—as well as body—destroying, but that has not been the result of our investigations. There was one case of a man who all day long did little but step on a treadle release. He thought that the motion was making him one-sided. The medical examination did not show that he had been affected, but, of course, he was changed to another job that used a different set of muscles. In a few weeks he asked for his old job again. It would seem reasonable to imagine that going through the same set of motions daily for eight hours would produce an abnormal body, but we have never had a case of it. We shift men whenever they ask to be shifted, and we should like regularly to change them—that would be entirely feasible if only the men would have it that way. They do not like changes that they do not themselves suggest. Some of the operations are undoubtedly monotonous—so monotonous that it seems scarcely possible that any man would care to continue long at the same job. Probably the most monotonous task in the whole factory is one in which a man picks up a gear with a steel hook, shakes it in a vat of oil, then turns it into a basket. The motion never varies. The gears come to him always in exactly the same place, he gives each one the same number of shakes, and he drops it into a basket that is always in the same place. No muscular energy is required, no intelligence is required. He does little more than wave his hands gently to and fro—the steel rod is so light. Yet the man on that job has been doing it for eight solid years. He has saved and invested his money until now he has about forty thousand dollars—and he stubbornly resists every attempt to force him into a better job.

Henry Ford

From My Life and Work. Born in Wayne County, Michigan, in 1863, Ford took to mechanics as a child, building his first steam engine at the age of fifteen. The following year he walked to Detroit to find work in a machine shop. In 1891 he was hired by Thomas Edison’s Electric Illuminating Company, where his interest in internal combustion engines led him to construct the first Ford engine, and he was promoted to chief engineer. Thomas Edison remained a lifelong friend and mentor. In June 1903 Ford and twelve others invested $28,000 to create the Ford Motor Company, which sold its first car a month later.