Children and fools cannot lie.

—John Heywood, 1546Dead Alive

Lawrence Osborne prices the cost of a fake death.

Years ago, while flying from Bangkok to Phnom Penh, I read what could be called a local novel by a Bangkok private investigator named Byron Bales. The Family Business was written with an entertainingly maniacal attention to detail and a world-weariness perfectly matched to its material: an American couple who plot to stage the husband’s death in Manila in order to claim insurance money back in the United States.

The British call this kind of faked death “doing a Reginald Perrin,” after a 1970s sitcom hero who stages his own suicide and then comes back to life to start all over again. The British, after all, can never forget government minister John Stonehouse, who disappeared on a Miami beach in 1974. Stonehouse was later found in Australia, using a forged passport under the name Clive Mildoon. It’s the ultimate travel experience: reincarnation in a distant place as an insurance scam. Insurance agents call it “pseudocide.”

Bales spent more than thirty years as an investigator, ten of them in Bangkok, tracking down people who had disappeared, faking their own deaths in order to dupe America’s gullible and often chaotic insurance companies (it’s an industry in decline, he insinuates). I learned from the back cover of The Family Business that it was based on several cases that Bales himself had investigated. So people really do disappear, I thought, and they really do collect the money.

It’s a travel idea you can’t resist. You fly to an exotic country, check into your hotel and then you die. Having died, you do a Reginald Perrin. You get paid hundreds of thousands of dollars by a clueless corporation eight thousand miles away and then carry on living in the country where you were vacationing. Certainly, you’d never see your children or your old mother again. But look on the bright side. You’d have no debts and you could start again, and if you were lucky you’d have turned a profit.

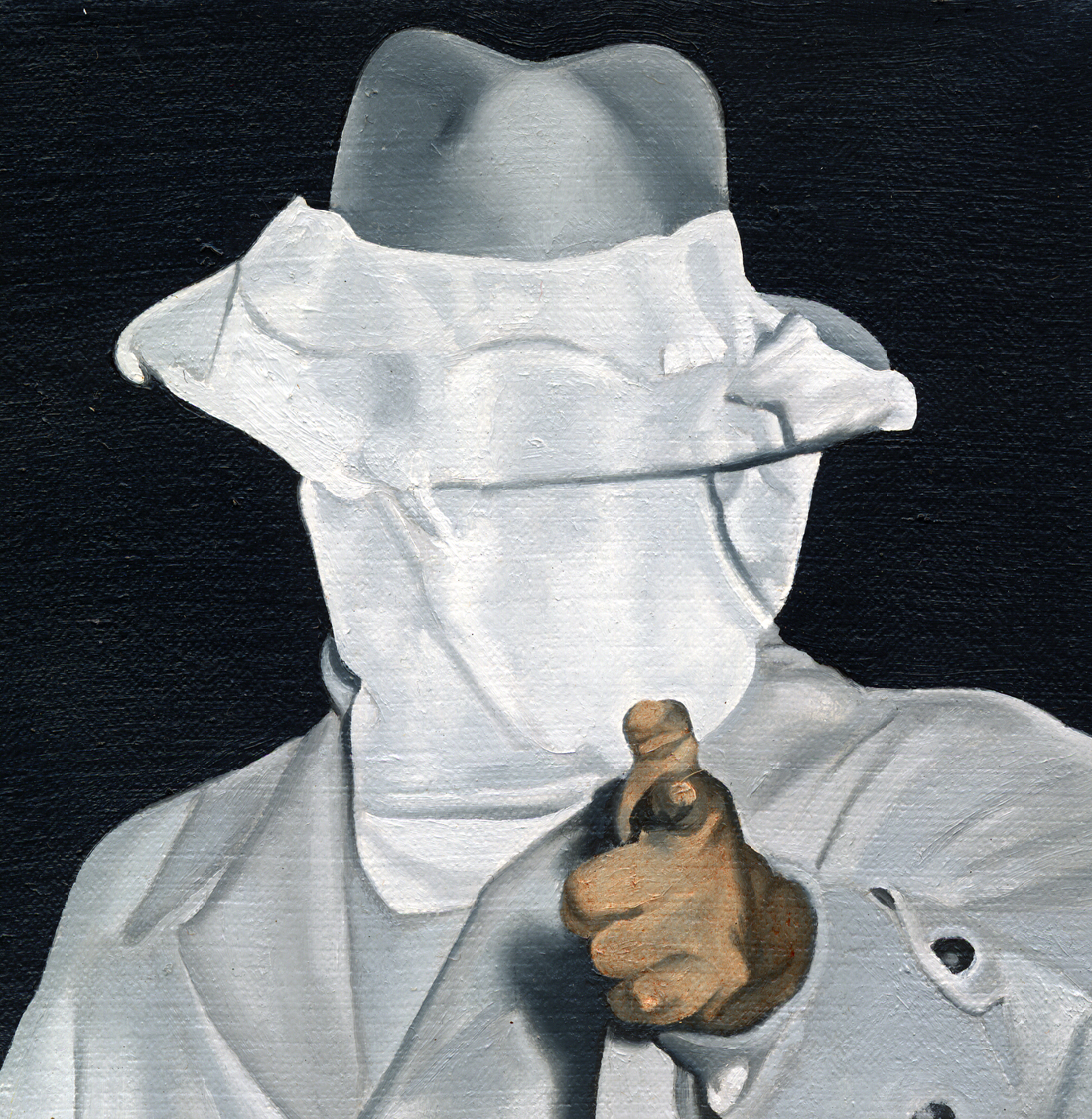

Worst Case Scenario (VII), by Dotty Attie, 2013. © Dotty Attie, courtesy the artist and P.P.O.W Gallery, New York.

For years I wondered if this were really possible. In many bars in Bangkok, Vientiane, and Phnom Penh I would run into characters who claimed they had run away from their lives. Some had changed their names; others wouldn’t admit how they had gotten there—they would tap their noses and say, “I’m not the man I was.” I’ve always thought there was a dark pleasure in being an impostor, like traveling on a train and telling people you meet that you are an invented character. When I was a child traveling on English trains I used to tell strangers that I was “Prince Prinzapolka,” and it was always satisfying to see them buy it. These grown men had done the same.

But how many of them had staged their own deaths? It seems like a stunt that would be both disarmingly easy and inexpressibly complicated, even in Bangkok. Bales had pointed out that as soon as you were “dead” you could no longer use a credit card. You could not walk insouciantly down a city street or make a phone call to your family. In a social sense, you really would be dead, and you’d have to adapt to the fact.

Crossing borders loaded with cash would be nerve-racking, airport security would be an ordeal, and your intimate relations would have to begin at ground zero.

I was curious to see how easy it is to be declared dead. I didn’t want to disappear, but I was fascinated by the idea that I could. What would it feel like to see one’s name on a death certificate and know that one’s demise was officially recorded in a government database?

Because I have a long association with Thailand, I didn’t want to try there. Instead, I flew to Manila a few months later and sublet an apartment in Makati City behind the imposing fire station on Ayala Avenue—one of Manila’s most upscale and internationalized but suitably anonymous neighborhoods. The apartment was in a high-rise tower, and outside the front door was an unremarkable side street.

Manila is different from Bangkok. It has a gun culture with a more violent, reckless streak. There is a greater feeling of corruptible chaos. The Philippines is one of the most bureaucratic countries in the world and therefore one of the easiest in which to get things done with the right tip. It’s also much more Americanized. English is spoken as much as Tagalog among many classes. And most important, Manila is a megalopolis, with a population of twelve million. I could see why an American would come here to disappear.

The problem with forged certificates is that they are not registered with the government. This means a scrupulous insurer, or its investigator, could easily prove their illegitimacy. It might work for smaller scams, but for big money I’d need a real death certificate registered with the local civil registry. In Manila, that means the registry in Manila City Hall. I would have to go there and try to turn a clerk. This is what many a scammer has done in the past. But it was possible that times had changed. I was told all you needed was charm and a crisp new bill.

City hall stands at the junction of Almeda-Lopez and Padre Burgos Street in the old part of town near the Spanish core of Intramuros. It’s a decaying neoclassical pile with a polychrome Jesus in front and bamboo scaffolding everywhere. Many of its windows are blocked with irrational cinder-block walls or plywood panels, and by the gates are countless notices announcing no fixers allowed, which I thought was rather a shame because never would a fixer have been more useful.

I went through the courtyard in sunglasses and was directed by the armed police to the registry. It was packed with people seeking birth certificates. As I waited to see a clerk, I wondered what the prison term was for bribing them or whether it would all be brushed off in good humor. Eventually, one way or the other, I had my clerk: a youngish man in a nice shirt with blade-like creases. When he asked me what I wanted, I said, “I am doing research on statistics and was wondering if I could meet you for coffee outside.”

There was no reaction of surprise. An hour later we were walking through the Central Terminal Station nearby, through dark arcades of fast-food outlets and vendors of empanadas especiales, the clerk in his pressed shirt, me with slightly shaking hands. There was a dingy eatery called Manileno, where horse races were being broadcast, and we sat there because no one would pay us any attention. I bought him lunch with a glass of milky buko juice, and he ate his squid balls slowly. We gazed out a little mournfully at a pawnshop called Palawan and a blind busker strumming a fake Stratocaster.

“So what are you researching?” he asked.

I said quite bluntly that I wanted a death certificate.

“What for?” he said.

“That’s my business.”

“No, actually, it’s my business too.”

I said I wanted to claim the insurance money. I figured any other explanation would sound false, and that he knew perfectly well what I wanted it for.

“I see,” he murmured and calmly gave me the price. It was one thousand pesos for the certificate and one thousand for himself. That made about fifty dollars in total. I agreed, but as we sat there I felt he was changing his mind. He wasn’t sure about me, and there was something, perhaps, in my manner that was not genuinely desperate. Then I realized I had forgotten to haggle. A real criminal always haggles, even over a twenty-five-dollar certificate. I should have pushed him down to fifteen dollars.

It was a mistake, and as we walked back to city hall along Villegas Street and through the tropical park next to the university, I felt he was getting cold feet. Finally he said he couldn’t do it, but he asked for my number all the same. He could ask someone to ask someone to ask someone, and perhaps they could help. He smiled the whole time, with the gentle irony of the Filipinos, and there was no judgmental distaste in his refusal. It was too risky for him to undertake. I said I was sorry, and he said, “No problem.”

Two days later the phone rang. A cheerful woman’s voice. She asked me what I wanted. I gave her my details, and then she asked, “When did you die? And how?”

“Yesterday,” I blurted out. “I died yesterday and I think it was a heart attack.”

“You think?”

“I wasn’t there,” I said, and she laughed.

“I’ll see what I can do,” she concluded. “It’s one thousand pesos for the certificate, and you can give me the same if you like.”

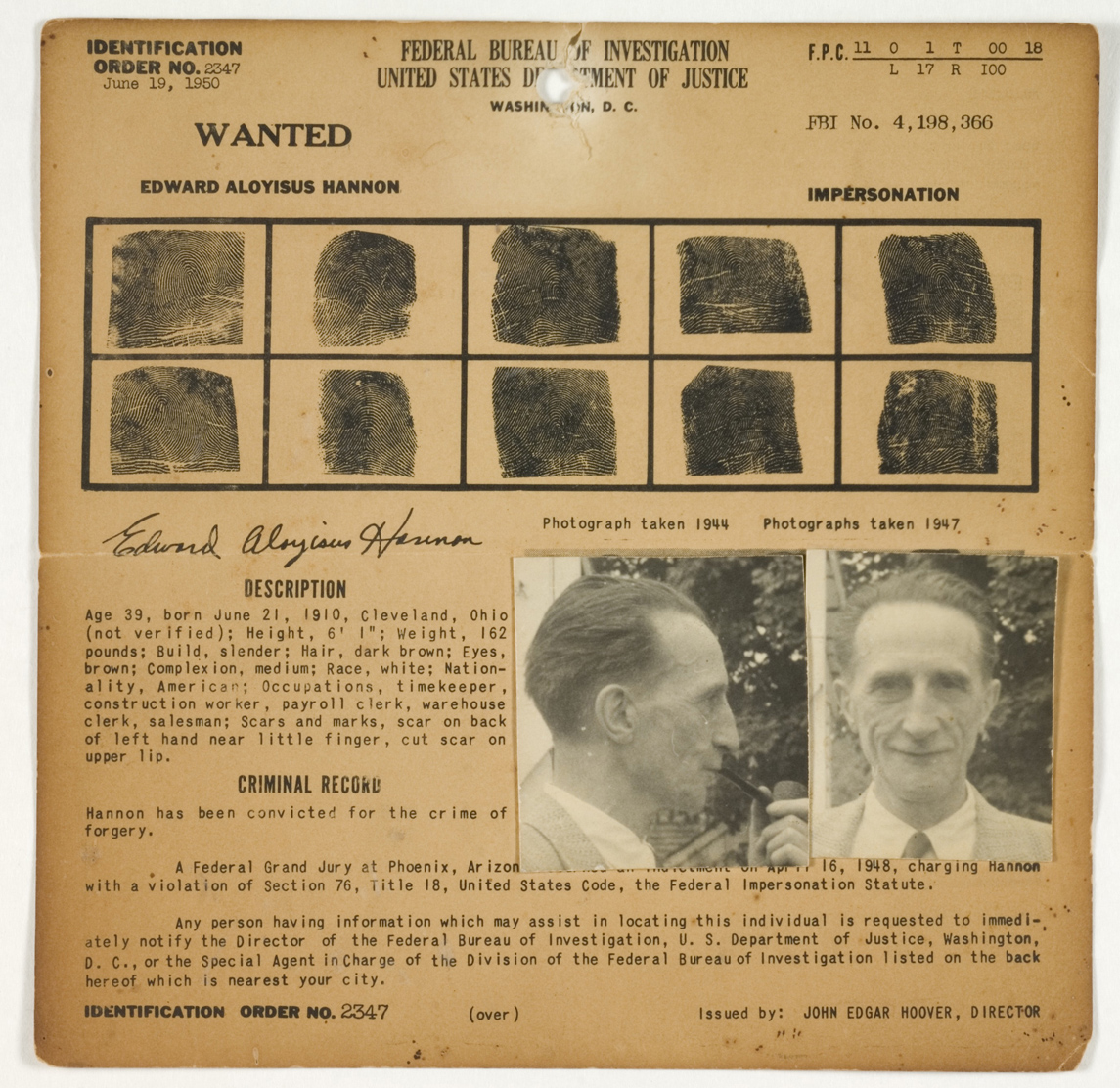

FBI Wanted Notice: Edward Aloyisus Hannon (Marcel Duchamp), Wanted for the Crime of Impersonation, by Julien Levy, c. 1950. © Philadelphia Museum of Art, Pennsylvania, PA, Bridgeman Images

The next twenty-four hours felt like my last on earth, or at least how my last twenty-four hours of normal life would feel if I were about to disappear. There was the slight fear I had blundered too far and that a police car would arrive downstairs looking for the gringo insurance fraudster.

But nothing of the sort happened. Instead, the same woman called me back and told me my death certificate was ready and would be delivered to my apartment by a courier who would anonymously leave it at the front desk of my apartment block. I would see no one and ask no questions.

As I went down to collect it I thought of Steven Chin Leung, the Hong Kong national who had managed to have himself named as one of the 650 Cantor Fitzgerald employees who had perished in the World Trade Center on September 11, 2001. What had gone through Leung’s mind as he saw himself plastered over the national media as a dead person? Glee, ecstatic satisfaction, or unnameable dread? He later claimed he was using his death certificate to avoid a prior offense related to obtaining a U.S. passport, but there might well have been more to it than that. For myself, there was an acute anticipation at the idea of being declared nonexistent. I was sure it was going to feel like walking through an open door on the far side of which lay a possibility that could be savored without being seized. My own certificate was in a pale blue envelope stapled at both ends. I took it upstairs with a morbid unease.

This was an official death notice signed by a doctor in a hospital in the Sampaloc neighborhood in Manila, and it bore official government stamps. I was identified as a Catholic who had succumbed to a condition named as “pulmonary acute,” and my body was designated as ready for burial. My closest relative was named at the bottom of the form as one “Jasmin Osborne,” my “auntie” whose delicate signature appeared above. I wondered how they had guessed that far from having a weak heart I do actually suffer from acute and chronic emphysema. I had died at midnight, needless to say.

It was then that the mentality of tago ng tago—hiding and hiding—finally set in, and I felt strangely emboldened to assume the pleasures of fakery and pseudocide. Like Reginald Perrin, I started to go out under an assumed name, telling people I met in bars and clubs that I was John Jones and worked as a banker at a Singapore firm. I could have said Prince Prinzapolka and they would not have batted an eyelid. It was easy to tell people whatever you wanted. It was disturbingly easy to imagine carrying on like this indefinitely. The pleasure, deep down, was not that of making illicit money but simply of no longer being who you had been.

Lawrence Osborne

From “Disappearance in the East.” After studying at Cambridge and Harvard universities, Osborne lived in Paris, New York City, Mexico, and Istanbul, working primarily as a travel writer and journalist. He currently resides in Bangkok. “Very few writers live here, of course,” Osborne said in an interview. “But that’s quite all right with me.” His travel narrative through the Middle East, The Wet and the Dry: A Drinker’s Journey, was published in 2013, as was his second novel, The Forgiven. His most recent novel, The Ballad of a Small Player, was published in 2014.