Pages from the Chicago Defender and Metropolitan News, twentieth century.

To the Profession.

Ladies and gentlemen: I find it necessary to explain my position as a writer on the Freeman. I write under signature as a special “Musical and Dramatic Critic.” This is plain and already understood to the intelligent people. My efforts are for the best interests of performers and productions. My standard is “Justice to all” and “partiality to none.” I insult nobody and pay no attention to ignorance. The most deserving performers must be better presented in these columns hereafter and the ignorant outsiders who write disparagingly about stage people will find me in a solemn waterloo.

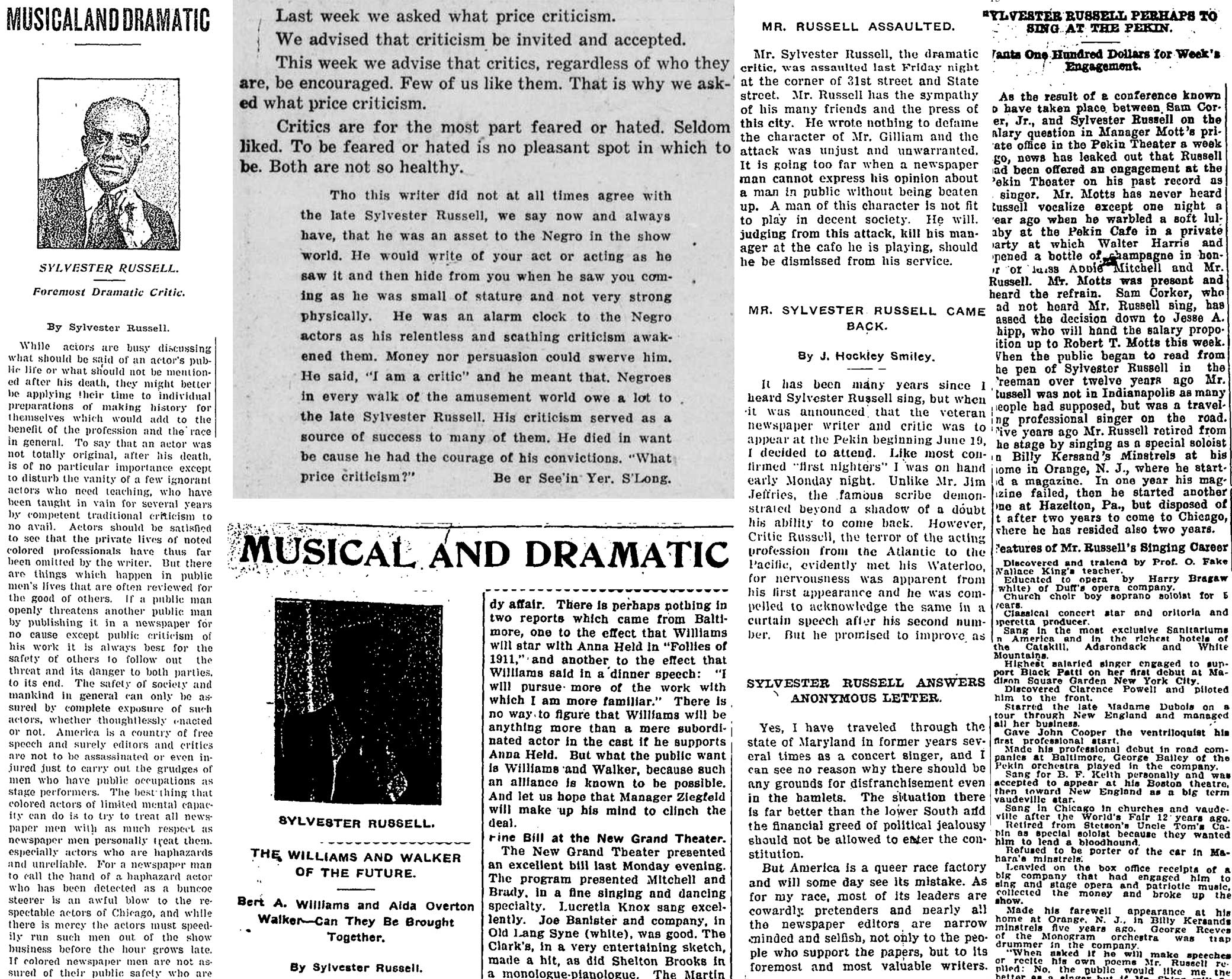

sylvester russell

By this notice’s 1902 publication, readers of the Indianapolis Freeman knew that Sylvester Russell, the first Black arts critic to gain national recognition in the U.S., was a man of strong opinions. Russell used his role as a popular critic to share his incisive vision of Black music and theater with the general public. Decades before musicologists examined Black performing arts with the same seriousness they offered white, European-derived traditions—and well before Black ethnomusicologists would earn the long-deserved respects of their peers—Russell used his column to argue for the perfection and elevation of Black performance on the popular stage.

He saw a path for racial uplift through his consideration of Black performers’ work, driven largely by the development of a systematic musicology, or study of musical form and practice, that set African American performance on a scale from cheap blackface minstrelsy to the finest operatic vocals. His columns ranked artistic works in a sort of hierarchy ranging from “low comedy/minstrelsy” at the bottom to classical composers like Samuel Coleridge-Taylor at the top. He took part in artistic debates that continue to unfurl on the internet today.

Throughout his career, which lasted until his death in 1930, Russell wrote for the major Black papers of the day—the Indianapolis Freeman, later the Chicago Defender, and finally the Star, a theatrical paper he published himself—from his perch in New York City, the capital of the performing arts. He viewed his readers as advanced experts on Black music and culture, and he knew that his audience deserved a critic that could meet its expertise with the analysis it merited and couldn’t get anywhere else. And he recognized his methods were innovative and advertised them as such, as in this review of a 1902 production of the musical In Dahomey, playing at the Grand Opera House in Brooklyn, which mentions William Randolph Hearst’s theater critics James J. Montague and Alan Dale, two of the most influential cultural critics at the time.

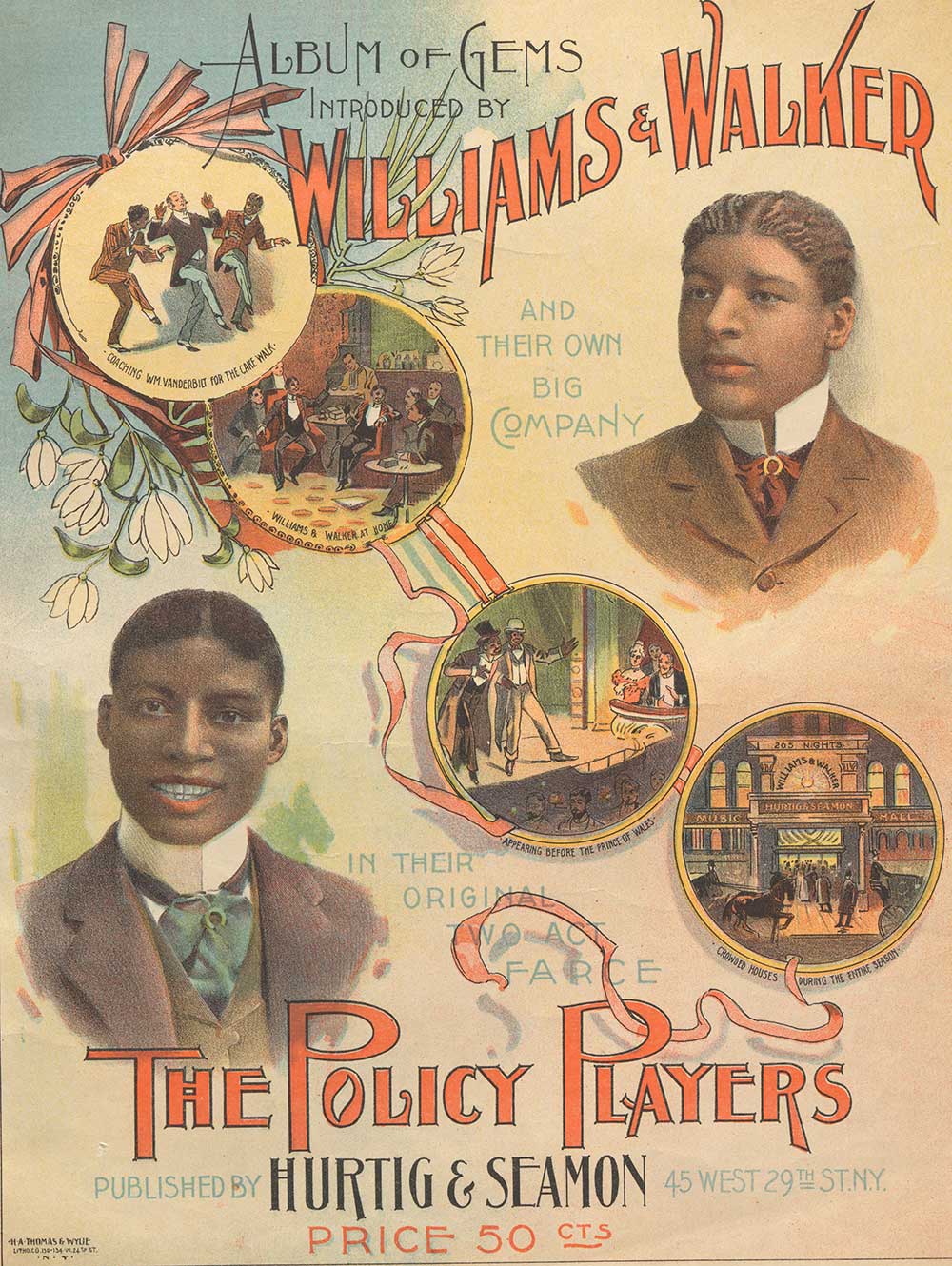

The Freeman’s method of stage criticism will be found to be no different from that of the New York Journal. The James Montague and Alan Dale methods are acceptable to the Journal’s advanced readers. The Sylvester Russell methods are acceptable to the Freeman’s advanced readers. Montague writes about “Mascagni.” He knows about his music even if he can’t sing it. Dale writes about Weber & Fields. He knows about comedy even if he can’t act it. Russell writes about Williams & Walker. He knows “coon comedy” and all the branches of music that go with it. Montagne and Dale are not so well advanced in coon art as Russell. They know coon comedy is young and as all their time is taken up reviewing the other races, the burden of weeding out the coon comedy garden falls to Russell and the Freeman.

Russell’s detailed analyses paint a picture of a thinker uninterested in seeking the approval of the white critical gaze. Dale was equally as harsh in his reviews as Russell but had the prestige and access of the white newspaper apparatus, and Russell wrote a response to the popular Black actor and producer Billy McClain’s comparison of the critics in 1903.

McClain addressed me as the black Alan Dale. I have also been called Alan Dale in bronze. I am neither the black nor the bronze Alan Dale. My true knowledge of negro performances may be a little better than Dale’s—who knows—but possibly not quite so expansive. What I choose to say about McClain may weigh heavier in the balance than what Dale says. If Dale could see the scales he might be contented to have himself called the “white” Sylvester Russell.

The critic had a clear desire to establish African American music as a field worthy of study, with a history and progressive development. His examination of Black music for a Black audience was a direct challenge to a world where white people in blackface had been allowed to define the musical and performance qualities of what it meant to be Black.

The turn of the twentieth century was a transitory period for Black performance. From the 1830s onward white musicians, dancers, and comedians had appeared in shows with faces painted Black, cruelly and garishly burlesquing Black life. In the postbellum period blackface minstrelsy was no longer primarily the domain of white performers, but it was still the most popular art form of the day. White performers in blackface, Black performers in blackface, Black performers in elegant suits, and white performers imitating them were all featured on the American stage. The showman’s desire for innovation and authenticity led to minstrel troupes full of Black performers, performing for primarily white audiences.

At the same time African Americans were beginning to study Western art-song and classical music traditions, and other Black performers debuted minstrelsy-influenced styles presented from a Black authorship. Russell judged and praised the changing scene while working toward an overarching goal of lifting up the entire cultural ecosystem in which these performances existed.

His oeuvre demanded that performances be received on their merits. Writing at a time when white critics often assumed successful Black artists had innate and untrained skills, Russell provided pedagogical critiques of histories he deemed inaccurate. Blackface minstrelsy garnered much of its early success from the racist idea that the genre combined authentic Black folk styling with the polish of white compositional hands. The banjo, an African stringed instrument taught and played by enslaved Black people in the Americas, was popularized in minstrelsy by the white performer Joel Sweeney. A mythos then developed around Sweeney, who was said to have added the fifth string to the banjo because he was unhappy with the limited melodic possibilities, thus elevating it to the popular instrument it became in the nineteenth century. Stephen Foster, composer of the still-famous tunes “Camptown Races” and “Oh! Susanna,” wrote many dialect songs for the minstrel stage; he thought of himself as elevating the text from what he called “the trashy and really offensive words which belong to some songs of that order.” Russell balked against an artistic order in which Black creativity was a footnote to white creations, writing in 1901:

Mr. Barnes of the white Vaudeville team of Barnes and Sisson…gave out the erroneous report that Stephen C. Foster was the first writer of coon songs. Mr. Foster extracted “Old Folks at Home” and “Kentucky Home” from hearing the slaves sing. We will have Mr. Barnes to know that slave songs are not coon songs. Coon songs were originated by colored comedians in southern minstrelsy years ago. Ragtime music was discovered in colored piano players who played by ear or sound, a movement recently discerned.

Russell also found it necessary to criticize the most popular performers of the day, including the vaudeville comedians George Walker and Bert Williams, who had gained fame outside of the Black theatergoing community. He argued that being harsh ensured white audiences wouldn’t have a flimsy excuse to dismiss his endeavor.

Upon these grounds intelligent white people base a silent argument that Negro actors are not yet well enough educated to classify their own works. Everything and anything is looked upon by them as common coonism simply because we do not know enough to classify our own work.

Walker and Williams were the stars of In Dahomey, which had its Broadway premiere in 1903 at the New York Theatre. It was the first musical composed and performed by African Americans on a main Broadway stage, with lyrics by Paul Laurence Dunbar. The loose plot primarily served to present the music and dancing. The musical follows con men Shylock Homestead and Rareback Pinkerton, played by Williams and Walker, through antics in Boston, Florida, and eventually Dahomey (now Benin). Its songs played up ideas of back-to-Africa colonization, mocked whites who mistreated Black people by assuming inferiority, and satirized bourgeois Black people. Confusing plot aside, the play was a rousing success among Black and white critics and audiences alike, with a multi-month run and a European tour that included a performance for the British royal family. Even that couldn’t blind Russell’s perfectionist eye.

In a 1903 column titled “Doctrine of George W. Walker”—published eleven days before In Dahomey moved to Broadway from the Grand Opera House—he explained why Walker, one of the most famous Black performers of his day, had been the subject of so much of his critical ire.

In summing up the deal of criticism of the past year, a vast amount of it fell unintentionally upon him. There was no special cause for this except for his defective style of dressing for low comedy. This defect does not mar his ability as an actor, but rather reflects upon the playwrights. But Negro comedies have been put together so much by botchworkers, it is hard to tell who the authors of any of the plays really are. The quality of acting depicted by Mr. Walker is of such an odd type that there is scarcely any of the writers with whom he has been associated who had the ability to write a part classical and witty enough to suit the requirements of his personality. Mr. Walker is not a low comedy comedian. He will only be able to sustain his reputation in high Negro comedy and classical features.

Russell’s critique kept going:

As the cleverest talker of his race on the stage, what can he say beyond the limits of the botchworkers? What can he do as a faddest when noted composers, who advertise themselves at his expense, fail to write him a song that will make him shine?…Playwrights can answer back and say: If actors want to keep dressed up why don’t they say so? White actors commission the playwrights to do “thus and so,” and this means that both Mr. Walker and the botchworkers will learn to think a little more hereafter.

Like other critics of the early twentieth century, Russell began his career as a performer. In the late 1880s he began to appear in the theatrical notices as Sylvester Russell, a professional transformation from his previous life as Harvey Russell, a student’s valet at Brown University. Performing primarily in sacred and art-song recitals, Russell bristled at attempts to be classified as just another minstrel entertainer; he responded to positive coverage in the New York Age in 1891 with a letter to the editor derisively titled “Sylvester Russell Angry: He Says Some Managers Have Gall,” clarifying that he was a member of no minstrel troupe and would “hereafter be known as the famous countertenor.” He must have been pleased to see his quips in print because he kept writing. By 1898 Russell had mostly transitioned away from the stage and into the seats, where he critiqued Black performance in a truly distinctive voice.

Russell’s uncompromising respect for Black Americans was not limited to the stage. On February 23, 1903, Russell entered Wolf’s Dairy Lunch Cafe in Providence, Rhode Island, and sat at a table in the front of the restaurant. When a waiter asked him to move to a segregated seating area, Russell refused. The waiters would not serve Russell until every white patron had left the restaurant. Russell commented that the other guests were sympathetic to his claim, writing that “the color line is drawn more by waiters than by guests or proprietors.” He was particularly angered by theater owners who segregated Black patrons coming to see Black performers. That same year Russell called out Jewish-owned theater owners, who experienced segregation themselves at resorts and private clubs but then segregated their own theaters instead of acting in solidarity with Black audiences.

The public cares nothing about where a respectable colored person sits, in the northern theaters, in this enlightened age. The thoroughbred white people would be delighted to sit next to the families of Bishop Derrick, who rode with a foreign prince, or Booker T. Washington, who dined with the president, and converse with them.

This commentary betrays the respectability politics that Russell’s worldview was built upon. Some authors and activists, notably W.E.B. Du Bois in his famous 1903 essay “The Talented Tenth,” were arguing that it was the responsibility of Black people with access to education and leadership potential to serve their community through political engagement and the presentation of a culture recognizable to white people as elevated and worthy. While racial uplift was a common organizing principle for Black Americans at the turn of the twentieth century, Russell subverted the standard by allowing a place for low comedy and blackface minstrelsy. Black performers, composers, and producers read Russell’s works and begrudgingly respected his unwaveringly blunt tone, though musicologist Eileen Southern pointed out in her 1982 Biographical Dictionary of Afro-American and African Musicians that he was “more than once physically assaulted for his criticism.”

Striving to create a system for understanding Black performing arts to rival those that had existed for centuries around Western European performance, Russell used his pen to order the world and insisted that everyone else follow his lead. In a 1903 column titled “Immigration Questions,” in which Russell discussed Black performers in Europe and the potential benefits of seeking success abroad, he wrote,

The voice and the color seems to be the main thing which attracts in the old country. Dancing is a second party. Negro dialect and nonsense is a good third. Ragtime coon songs are scarcely understood by the natives as a whole, and it will be a long time before the people are up to their humor.

This pragmatic description subverts assumptions that European viewers were by nature the most discerning, casting it as a cultural and intellectual deficit that continental audiences didn’t respond to modern African American lyrics and sounds.

By the time of his passing in October 1930, Russell had established himself as the old guard of Black arts criticism, leading the way for Black critics like Lester Walton of the New York Age in the mid-1910s and Nora Holt of the Defender in the following decade. Unlike Russell, however, Walton and Holt stuck primarily to concert music, not spending much time reviewing the equivalent Black popular music trend of their times: the blues. Russell’s rough shaping of a Black musicology that valued low and high art would fall into the background much as his critical voice did. Many of the particulars of his life are no longer accessible today; if a twenty-first-century scholar wants to build out a portrait of Russell’s life and influence, the only clear paper trail to follow is through his newspaper criticism. There is no public archive of personal writings, no “Sylvester Russell Collection of Manuscripts.”

Musicologist Matthew D. Morrison and his concept of “Blacksound,” defined as “the sonic and embodied legacy of blackface performance as the origin of all popular music, entertainment, and culture in the United States,” Daphne A. Brooks’ study of the intellectual life of Black women’s music, and Anna Everett’s and Jacqueline Najuma Stewart’s work on early Black film criticism and audience reception value and consider the influence of this era of Black performance and the performance of Blackness in ways that link back to Russell’s critical lineage. His criticism and focus on deep analysis of Black performance across genre made him a forebear of contemporary scholars, but it is perhaps the focus on styles like blackface minstrelsy and coon song that have helped Russell’s legacy remain somewhat forgotten. It has taken over a century for Russell’s ideas to be fully realized in a manner liberated from the social structures of early twentieth-century survival, reaching our current moment where Black performance is widely accepted as a core foundation of American arts.