I had fallen head over heels in love with Susan Brockman at Cornell in 1955. I met Susan when she was standing alone in the lobby of Willard Straight Hall, the student union. She was looking so intently at a mural depicting a youth trying to subdue a unicorn that she didn’t notice me. I asked her if she identified with the youth or the unicorn. Without turning her head, she answered, “The unicorn.” When I tried to keep the conversation alive by saying, “Unicorns don’t exist,” she replied, walking away, “Neither do I.”

Despite that inauspicious beginning, I persisted with a tenacity of which I did not know I was capable. As I got to know her, I realized that though we had come to Cornell from Brooklyn, and from fairly similar Jewish middle-class backgrounds, she had ascended to a world that I had only read about in books and magazines. She knew such illustrious figures as the surrealist Salvador Dalí, who, while I watched, splattered an egg on the wall of her home in New York to gift her what he called an “original Dalí”; the conductor Leopold Stokowski, who invited her to all his performances at the New York Philharmonic; the photographer Robert Frank; and the abstract expressionist painter Willem de Kooning, who was pursuing her.

Soon after meeting Susan I was suspended from Cornell. I had no idea what to do with my idle days or how to continue seeing Susan. I asked her if she had an ambition and, to my utter surprise, she said that she had always dreamed of playing Helen of Troy in a movie adaptation of the Iliad. A few weeks later I read a story in the New York Times reporting that Zervos Pictures in Athens and Mosfilms in Moscow had tentatively agreed to make a Russian-Greek coproduction of the Iliad. I was taken by an absolutely insane idea: if I produced the Iliad, I could cast Susan as Helen. Seizing the opportunity, I dashed off a telegram to Zervos Pictures in Athens:

if you are not irrevocably committed to the russians, would you consider doing instead an american coproduction with marlon brando as achilles, james mason as agamemnon, richard boone as odysseus and susan brockman as helen of troy.

I could not send it immediately because I was concerned about my return address. I was living at my parents’ home in Rockville Centre and feared that asking Zervos to reply to Ed Epstein c/o Betty & Lou Epstein might cast my credibility as a producer into question. Susan’s sorority house at Cornell, Alpha Epsilon Phi, had a similar problem, but Susan found the solution: her father.

David Brockman, a successful financier, had an impressive address, which I used as my return address. About a week later, David Brockman received a telegram from George Zervos, the president of Zervos Pictures:

i am willing to put up 7 million dollars for below-the-line production stop prefer to do the iliad with epstein’s company instead of the russians.

As David Brockman had not seen my original telegram offering to provide Marlon Brando, he was impressed that someone would offer a friend of his daughter $7 million (the equivalent of $56 million in 2022). He asked Susan to arrange for me to meet him and Arnold Krakower, a successful New York divorce lawyer. The meeting then expanded to include another of Brockman’s business associates, Ben Javits.

Ben was the brother, éminence grise, and law partner of New York senator Jacob Javits. He reveled in the idea of influencing world events, or at least Grecian ones, by blocking a Russian coproduction. He offered to have his brother write letters to everyone who mattered in Greece.

Even though I had not previously conceived of my adventure as part of the Cold War, I accepted his offer. Why not block the Russians? At Krakower’s suggestion, we formed a partnership—Iliad Productions, Inc.—in which Javits, Brockman, and Krakower would provide initial money for preproduction.

“You have to go to Athens right away,” Javits said with urgency.

On September 15, 1959, Susan and I made our initial trip to Greece. Her father, who owned a travel agency, among many other companies, provided us with first-class tickets to Athens on a KLM “sleeper” flight. As promised, Javits had opened every door for us. Over the next week, we met government ministers, shipping magnates, and others in the Athens power elite who had responded to Javits’ letters. We had a great time being wined and dined.

The first deal I made was with Spyros D. Skouras, the namesake nephew of Spyros Skouras, chairman of 20th Century Fox. Skouras owned a local film studio in Athens (Skouras Films), as well as the lucrative Eastman Kodak film franchise for all of Greece. After he listened to my plan for the Iliad, he asked who would play Achilles. When he heard Brando’s name, he became so excited that he wanted to sign a contract that day.

“Forget Zervos, forget the Russians. I will be your partner—but you must get Brando.”

I told him Brando had not yet agreed.

“He will,” Skouras said.

Two days later, Skouras and I signed a memorandum of understanding stipulating that I would supply Brando, the script, and the director, and Skouras would pay for the production in Greece. Next, Minister of Industry Nikolaos Martis, moved by Javits’ letter, offered a battalion of soldiers from the Greek army, horses from the King’s Guards, and whatever else I needed. He then said he would also like to host a small dinner at his home for Brando.

“When will Marlon arrive?”

I explained that Brando would need to approve the script. “Just give him Homer’s Iliad to read,” Minister Martis suggested.

He wrote a letter stating, “I will do everything in my power to ensure that every reasonable facility is provided by the authorities.” With this impressive-looking letter from Minister Martis and the agreement with Skouras Films, Susan and I triumphantly returned to New York. A telegram was waiting from Skouras:

dear ed, it has become an obsession with me. we must get brando for our picture…spyros.

By this time Arnold Krakower had taken a hand in the search for a director. He suggested Sidney Lumet, whose divorce from Gloria Vanderbilt he was then handling. To accommodate Krakower, Lumet invited me for breakfast at his penthouse at 10 Gracie Square, which overlooked the mayor’s mansion.

Lumet, though only thirty-six, was no amateur. The son of an actor and a dancer, he had made his stage debut in 1928, at the age of four, at the Yiddish Art Theater. He had been nominated for an Academy Award for directing Twelve Angry Men.

After selecting my breakfast from a large platter of smoked salmon, I asked him about Brando, whom he had just directed in The Fugitive Kind. He said Brando would be perfect, and he would be “keenly interested” in directing it once Brando signed on.

“Do you have a script?”

“I’m still working on it.”

In fact, all I had was a thirty-page treatment written on spec by a talented playwright, Sloane Elliott, an aficionado of Homer who had traveled to almost all the Greek islands. He was not, however, interested in writing a shooting script. A script was not my only problem.

“Once you have a script, you will need to put $500,000 in an escrow account before Brando’s agent, Audrey Wood, will allow him to read a page of it.”

I had neither a script nor $500,000. Having made these cold facts of the conventional movie business clear to me, Lumet politely ended the breakfast and walked me to the elevator. While waiting for the elevator I told him that the Greek government was providing its army for the battle scenes and that Spyros Skouras was willing to finance the shooting of those scenes.

“I guess you could shoot the battle scenes with a second unit,” he said, as the elevator doors opened.

“With Achilles wearing a mask?” I asked. “So Brando could still be used by the first unit?”

“Let’s see how they turn out. Bye.”

I decided on a new strategy: first, I’d shoot the battle scenes in Greece with a Greek unit, and then get Lumet to direct Brando in a studio in America. Yet I still had to worry about the United States. Having been suspended from Cornell, I could be drafted at any moment. The alternative to the draft was joining a reserve unit, but, given the number of men with the same idea, all the reserve units had long waiting lists.

As it happened, my cousin David Rockower had the means to jump the cue; he knew the civilian administrator at the 442nd Army Reserve unit in New York, Mario Puzo. So I paid Mario $50 to jump the queue. Though only thirty-nine, Puzo was overweight and balding with unkempt hair, but he had a sort of street wisdom I did not. He would take me over the next five years to places I otherwise would not have seen, such as an illicit high-stakes poker game in Hell’s Kitchen, my first; a bookie parlor in the Bronx; and a Mafia-favored restaurant on Mulberry Street in lower Manhattan. He also introduced me to his pal Joseph Heller, whose Catch-22 was one of my favorite books, at his “Gourmet Club” dinner in Chinatown. When he told me he was a writer for magazines with names like Stag, I told him I desperately needed a screenwriter for the Iliad. A deal was instantly struck to kill two birds with a single stone: Mario would slip me out of my reserve unit in such a way that it would not interfere with my activities as a movie producer; I would pay Mario $400 for a forty-page shooting script for the battle scenes. After I brought Puzo to meet Krakower, he said, “I’ll give him the $400 and a contract, but no one will ever believe this guy is a writer.” Puzo did deliver the promised script, however.

Krakower showed no enthusiasm for a bifurcated movie. “You need a single director,” he said authoritatively. He then found a candidate: Lewis Milestone. Milestone was an old-timer par excellence. In 1927 he had won the first (and only) Academy Award given for Best Comedy Director. Krakower had recently met Milestone at a Hollywood dinner, and Milestone had complained that because of age discrimination he could not get a picture to direct. Krakower proposed the Iliad, and Milestone showed “real interest in getting back in the game,” as Krakower put it.

After our initial meeting, at which I gave him Puzo’s script, Milestone and I carried on a month-long correspondence about Homer. On first reading Homer’s the Iliad the previous year, I had envisioned the foot soldiers like pawns in a chess game. They were protected from the front by giant ox-hide shields but without armor, entirely vulnerable from the rear. In my concept, only the heroes—Achilles, Ajax, Hector, and Diomedes—had bronze armor. Once a hero cut his way through the line of enemy shields, he could slaughter the entire Trojan army unless opposed by an enemy hero, also in armor. This disparity could visually explain why heroes play such a decisive role in the Iliad.

Milestone—who had won an Oscar for All Quiet on the Western Front in 1930—found my idea impractical. After I described the shields in more detail in production notes, he wrote back, on March 18, 1960:

The prospect of doing the Iliad is exciting and inspiring, and my interest could not be more thoroughly aroused. However…your notes state that the extras will carry giant shields from which only their naked feet and head protrude. I must assume that the author of that sentence does not expect an extra to fall, nor to turn around, nor to pass the camera and be photographed from the rear.

Milestone had thirty years of experience as an action director, but I had an idée fixe. When he decided not to direct after discovering I had no funds to pay him, I proceeded with my giant shield obsession.

Returning to the idea of splitting the movie, I assumed, without any real basis, that I could find a Greek second unit director for the battle scenes and later induce Lumet to take over as director.

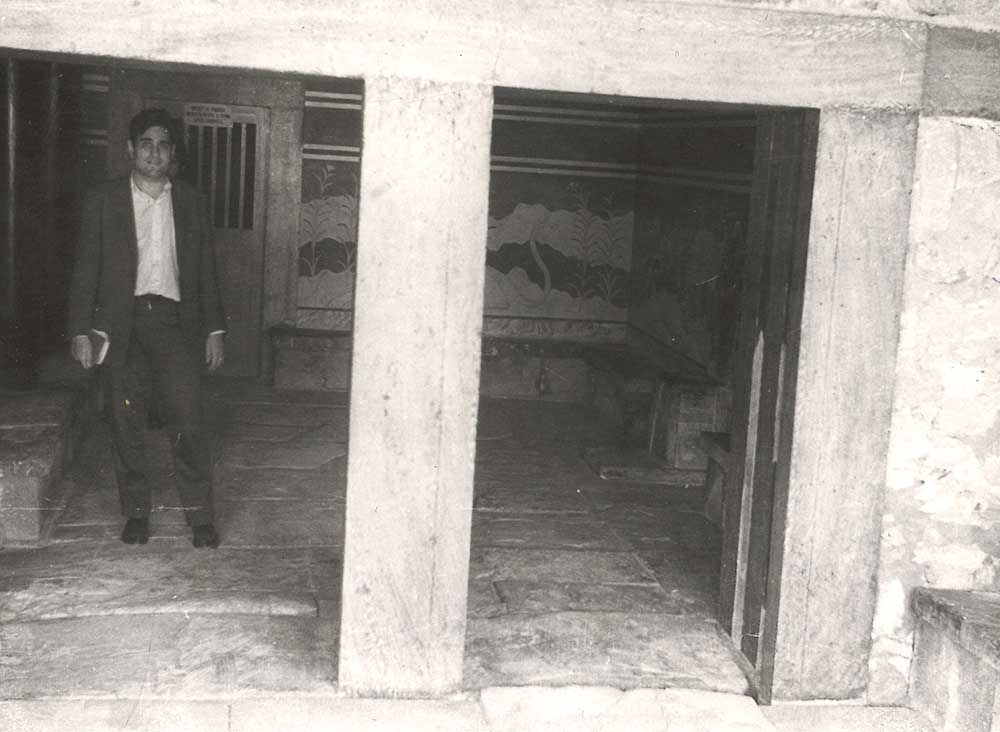

On July 15, 1961, I returned to Greece with Susan. She would supervise the design of the costumes, chariots, and other artwork. She took the costume design from vases she found in museums. They were loincloths, helmets, and sandals. We used student interns from an art school to fit them to the soldiers.

By this time I had raised $50,000 from Brockman, Krakower, Sloane Elliott, and my stepfather. We also got our plane tickets gratis from Brockman’s travel agency. We moved into the King George Hotel, where the owner, George Calcannis, anticipating the arrival of Marlon Brando, had given us the bridal suite. Finding the right location for the Iliad proved much more time-consuming than I had anticipated. In late July the Greek navy provided us with a spare gunboat, the BB36, to scout locations on various islands. We saw almost as many islands as Odysseus—Skyros, Andros, Hydra, Patmos, Lesbos, and Thíra—all with beautiful beaches, but none had the requisite electricity, hotels, or airport connection. Fortunately, by the time we returned from our futile search, Minister Martis had found the ideal location: a not-yet-occupied hotel on a deserted beach at Tolo that the Ministry of Tourism would provide free.

“Brando will be the first guest,” he added.

Meanwhile, the Greek Defense Ministry had appointed a colonel as our liaison with the Greek army. I drew call sheets based on both Puzo’s treatment and my imagination specifying how many extras were needed each day.

The script opened with a huge battle around the Greeks’ beached ships. For that spectacular scene, Susan and I had meticulously assembled ships, five hundred shields, two thousand costumes, and the other requisites. The Greek government had been most cooperative. For ships, the port of Piraeus contributed six waterlogged hulls long sunk in a caique graveyard outside the harbor. Shipping tycoon Stavros Niarchos contributed a floating crane to raise and load the hulls onto an LST landing craft—the L188—supplied by the Greek navy. The LST ferried them to the location. (Unfortunately, the LST broke its propeller unloading the cargo in shallow water.) Local authorities supplied a work gang of prisoners to reconstruct the ships. For masts, I had the prisoners borrow telephone poles from the surrounding area (temporarily interrupting local telephone service).

At this point, with shooting scheduled to commence in two weeks, I still had to fill the directorial gap. I cabled the London talent agency that was supplying me with three stuntmen in September. Could it also supply a second unit director? Enter, on September 7, Desmond O’Donovan, an ebullient Irishman with a great gift for gab. He told me he had produced a British TV show about a dog called Whirligig when he was just a teenager and, more recently, had worked uncredited with his half brother Kevin McClory on Around the World in 80 Days. With just five days to go before shooting, I was in no position to challenge even these scant credentials. So I sent him by taxi, along with the three stuntmen—Joe Powell, Pat Crane, and Frank Haydon—directly from the airport in Athens to the free hotel in Tolo.

O’Donovan decided that it was too cloudy to shoot battle scenes. Instead of following the script, he wrote a “weather contingency” scene in which a dog snatches a piece of meat from a pot at a campfire. He said it would provide a “cinematic metaphor” to depict the hard times the Greeks were suffering in their siege of Troy. In the aptly named Apollo screening room in Athens, I watched the results of this contingency with horror. There were thirty-seven retakes of the mangy dog.

Meanwhile, I was being billed daily for the cases of orangeade and mounds of shish kebab the 1,200 hungry extras consumed while waiting for the sun, draining a significant portion of my $36,000 production budget.

Watching the rushes with me were three visitors from Hollywood: Polish-born Rudy Mate, Russian-born George St. George, and a nineteen-year-old Italian actress, Maria. (I never learned her last name.) Rudy Mate had been a legendary cinematographer—photographing Carl Theodor Dreyer’s classic The Passion of Joan of Arc—before becoming a Hollywood hack director. He was in Athens to scout locations for his next film, The Lion of Sparta. George St. George—who had escaped the Russian Revolution via Shanghai and wound up in Hollywood—was Rudy’s producer and sidekick. Maria was, as became clear, Rudy’s lover. I had met them earlier in the day in the lobby of the Hotel Grande Bretagne and invited them to the screening.

“Interesting,” Rudy said after the dog’s twentieth lunge at the bone. (I later learned from Maria that “interesting” was Rudy’s code word for “awful.”)

“I’m not sure I am familiar with this director, O’Donovan.”

“It is his first film,” I replied. I added that the script was also by a first-time writer. His name was Mario Puzo.

“How did you get the Greek army?” asked George, intrigued by the cooperation I was getting from the Greek government.

“How did you get into this mess?” asked Maria, more to the point.

Over dessert in Cafe Floca, I explained how what had begun as a love story had turned into an organized flight from reality, with me as tour leader.

“That’s how we got the dog scene,” I concluded.

“Fascinating,” Rudy said. He, Maria, and George rose in unison to leave the Floca. “By the way, I wouldn’t want to contradict your director, but the best battle scenes I’ve shot were in cloudy weather.”

When I went back to Tolo, I gave O’Donovan new marching orders. Tomorrow, without any further delays, he was to shoot the establishing shot for the battle of the ships, which, according to Puzo’s script, was to be shot from a platform mounted in the water.

“I wish that it was possible, but you can see it’s going to be overcast tomorrow,” he said, pointing to the night’s sky. “But don’t worry. I have written a great contingency scene. It has a magnificent-looking old man—he must be ninety—tussling with the dog for his bone. It represents…”

“No old man, no dog, no more metaphors,” I angrily interrupted. Since Rudy Mate had told me his best shots in The Passion of Joan of Arc were shot in cloudy weather, I said, “Clouds or no clouds, rain or shine, shoot the battle scene.”

Werner Kurz, the director of photography, then raised the issue of his reputation as a cinematographer (even though previously he had only been a camera operator). “I will shoot in bad weather if you insist, but I will not put my name on the clapboard.”

“Neither will I,” O’Donovan said.

“Put my name on the clapboard as both cinematographer and director,” I volunteered, thereby expanding my portfolio of credits. Not having been on a movie set before, I had no idea how long it would take to prepare 1,200 extras for a single shot. At 7 am, the student interns from Athens began the somewhat precarious job of fitting the Greek soldiers into loincloths.

What made the task dicey was that Susan had meticulously copied the Trojan loincloth from a highly stylized vase in the Knossos museum that depicted a row of wasp-waisted Minoan warriors. But modern Greek soldiers did not have the same hourglass figure. Given the embarrassing mismatch, most of the extras insisted on wearing their polka-dotted boxer shorts under the loincloths, forcing the student dressers to make the necessary alterations on hundreds of the plumper (or less exhibitionistic) soldiers.

Building the camera platform on pylons during low tide was also time-consuming. The carpenters waded out to the half-sunk LST landing ship and, using it as a seaward base, began building the platform. They tested it by jumping on it, then rebuilding it when it collapsed.

Onshore, meanwhile, my German pyrotechnician, Karl Baumgarten, used a squad of prison volunteers to load each of the six ships with a ton of kerosene-soaked tires from a nearby waste dump. He then taught them how to smear incendiary napalm on the ship’s masts and railings. The stuntmen supervised the erection of stacks of cardboard boxes that would break their fall when they leaped from the fiery decks.

By noon the wranglers were still struggling to attach two large (and rearing) white horses, supplied by the King’s Guards, to a flimsy chariot built by the local blacksmith. The problem again proceeded from Susan’s brilliant effort to get life to imitate art. As with the loincloths, Susan had taken the design from a beautiful Mycenaean vase. Our imitation of this chariot overlooked the fact that horses had changed over three thousand years.

Finally, at 3 pm, after the crew had had their lunch, they waded out to the platform in a rising tide. Kurz tested the camera and signaled that it worked. O’Donovan signaled the assistant director, Eric Andreo. Baumgarten set the ships afire. The extras, all in position, raised their shields. The camera rolled. The clapboard—with my name on it—clapped “Take one.”

“Machē!” shouted Andreo over and over again. War! The soldiers did not move. It was a mutiny. They claimed the sand was too hot for their bare feet.

“Cut!” shouted O’Donovan.

While the dressers scrounged up sandals and rags for the soldiers to wear, Baumgarten’s crews put out the fires, which was not difficult since the telephone poles and prow heads had already burned to a crisp. The prisoners sent out a foraging party to gather more telephone poles from the road to Athens (thus adding to the area’s communications failures).

Meanwhile, the tide had risen nearly to the level of the camera platform. It was now 5 pm. The army was again placed in position, but this time, at my suggestion, the untested chariot (driven by Joe Powell) was set just behind the extras.

The fires were relit, the camera rolled, the clapboard clapped “Take two,” and the wranglers released the chariot from the guide ropes. The horses reared, hoofs flashing.

“Machē!” Andreo shouted. This time the soldiers charged forward into the gauntlet of burning ships, pursued by the chariot. The expressions of fear on their faces were not entirely pretense: they, like everyone else on the set, knew that the chariot had no brakes and was completely out of control.

“Cut! Great. Print it,” O’Donovan yelled, along with his one Greek word: “Efcharistó” (thank you).

Water now partly submerged the camera platform.

Then, finally, it happened. Six ships on the beach, doused in napalm, were set on fire. Since their hulls were waterlogged from the many years they had spent beneath the Aegean, all that burned were the local telephone poles and the plywood prow heads. And 1,200 scared Greek solders wearing loincloths and helmets ran into the blazing gauntlet between what remained of the ships.

O’Donovan strolled over to me in a bathing suit and suggested cutting out the Myrmidons, proposing to write a “cover scene” in which an old man with a lyre sings of the Myrmidons rescuing the ships. “It would be like the gods intervening.”

“Shoot the charge of the Myrmidons,” I insisted.

So Achilles’s Myrmidon contingent, carrying huge figure-eight shields that made them look like a swarm of ants, charged onto the beach toward the Greek ships. But, as in the last five takes, many of the extras stumbled or fell under the weight of their shields. Others stopped dead in their tracks. O’Donovan again yelled, “Cut!”

It was clear, alas, that Milestone had been right. As magnificent as the shields looked when stationary—an army of ant-men silhouetted on a ridge—they caused chaos in motion. Not only did they restrict the movement of the soldiers (not even the fear of the snorting chariot horses could prod them to run), but they also limited the angle of the camera.

Such unplanned battle scenes could not go on. “We are out of telephone poles,” the assistant director informed me. Apparently, the production inferno had consumed every pole for thirty kilometers. I suggested burning more rubber tires to mask the background ships in a cloud of smoke.

“Baumgarten says we are out of tires—and napalm,” Andreo added.

I suggested using diesel fuel from the LST, reasoning that with a smashed propeller it did not need fuel. Andreo sent the special-effects crew out to get the fuel.

As the sun set, the special-effects crew doused the ship in navy diesel oil, which Baumgarten somehow managed to ignite. The smoke began rising.

The soldiers again picked up their shields, the clapboard clapped “Take seven,” and I quietly slipped away. I had seen enough takes of the battle of the ships. I headed back to Athens to look at the new footage—and to consult again with Rudy Mate.

“The minister would like to know if Brando is in Greece,” said Spyros, industry minister Martis’ persistent assistant. Despite the report of a sighting of Brando reported in the English-language Athens News, I assured Spyros—as I had the hotel owner, the tourism minister, the army liaison, and the waiter at Cafe Floca—that it was a false sighting.

Nor would he likely arrive during my stay: I planned to depart Athens the next day for New York.

Back at the location, O’Donovan informed me he had exhausted the supply of diesel fuel from the LST as well as German napalm, junkyard tires, plywood prow heads, rope nets, and cardboard boxes. The work crew of prisoners had also so denuded the region of telephone poles that the telephone company had declared a state of emergency.

Nor were there any extras. The previous day, the colonel, who would go on to join the junta that overthrew the Greek government, had not only withdrawn the 1,200 troops but informed me as well that Iliad Productions would be billed for the expenses, including the missing diesel oil and the propeller for the stranded LST landing craft.

O’Donovan, who was still planning on shooting his “contingency scene” of an old man and a dog, was disappointed when I told him the shoot had ended and there was a bus waiting to transport him, the three stuntmen, and the German technicians to the airport.

“What about our wrap party?” he asked.

“Have it on the bus,” I offered.

For me, reality was beginning to poke its finger through the haze. All the money invested in the Iliad was gone—even the $20,000 supplement Susan’s father had generously added the week before. My Diners Club card was fatally encumbered with debt, including charges for the crew’s air tickets to Germany. I anticipated with dread the scary bill that would arrive any day from the Defense Ministry for disabling its one and only landing craft.

Susan, who had seen the rushes the previous night, was rightly concerned about the many gaps in the battle of the ships. She wanted to know why I ended the shoot so abruptly.

“Rudy Mate told me it was enough for a great battle scene,” I said to reassure her. In truth, Mate’s advice, after seeing all the footage, was expressed in a single word: “Enough.”

“But will you be able to do the rest of the movie in a studio?”

“First, let’s get it edited,” I temporized, spotting the huge frame of Spyros Skouras rising from a nearby table and approaching us.

“Is it true Brando arrives tomorrow?” Skouras asked. “Everyone is waiting…”

It was clearly time to leave Greece—and Susan agreed.

Soon after Susan and I returned to New York in October 1961, she moved to East Hampton, to try her hand at making art. Her parents had a home near the ocean and invited me to stay there so we could attempt to write a new screenplay of the Iliad. The home had a small theater in the basement, which Susan used to act out the Helen of Troy scenes. In early 1962 Susan told me that she had become romantically involved with Willem de Kooning. With little on the horizon in New York, I decided to return to Europe.

I rented a one-room apartment on Viale dei Parioli in Rome. I chose Rome because George St. George and Rudy Mate were there completing the postproduction work on their movie Lion of Sparta at Cinecittà, then the epicenter of sword-and-sandals epics. I thought that if I could locate an Italian producer willing to resuscitate the Iliad and find a way to finish the film, I might be able to win back Susan. I met numerous producers, but, unlike the Greeks, they required more than Richmond Lattimore’s translation of the Iliad, Puzo’s treatment, and the hope of getting Brando. Nor were they impressed with the battle-scene footage.

I came up with the idea of a movie in which the Iliad would be told from the prophetic point of view of Cassandra. It would be called Cassandra’s Iliad. I even found a possible Cassandra, Marie Devereux, who had been a body double for Elizabeth Taylor in Cleopatra. I met her on the set at Cinecittà and offered her the part. When I asked Puzo to write a screenplay for Cassandra’s Iliad, he turned me down cold, saying he was no longer interested in writing a movie that didn’t get produced. He wanted to write novels. He said he had an idea of a Mafia version of Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov, which he considered the most powerful book ever written about power. (Puzo’s novel The Godfather was published in 1969. The film adaptation, starring Marlon Brando, premiered in 1972.)

I next turned to my friend Sloane Elliott. Sloane had written the treatment for the Iliad and, to help finance the project, invested $10,000 in it. Even though he never recovered a penny, it was not a total loss. When he came to Greece in 1961 for the shooting of the battle scenes, he fell in love with Drusilla Vassiliou, the daughter of the movie’s production designer, married her, and moved to Greece. I now outlined to him my idea for telling the Iliad from Cassandra’s point of view. “Would you be interested in writing the screenplay?” I asked.

He replied with his own question: “Haven’t you spent enough time on the Iliad? You need to move on.”

He was right. Not only had I failed at producing the Iliad, but I had also used up every penny of a modest inheritance I had received on turning twenty-one. I could charge dinners on my Diners Club card, but I couldn’t pay the bill when it came due. The question was, move on to what?

It was becoming increasingly clear that without a college degree, my employment prospects were exceedingly dim. That left only one viable option—one that I hated: giving up my megalomaniacal ambitions and going back to college. If I could get readmitted to Cornell as an undergraduate and qualify for a student loan, I could get a degree. It was going backward, but I saw no other way of going forward.

Excerpted from Assume Nothing: Encounters with Assassins, Spies, Presidents, and Would-Be Masters of the Universe by Edward Jay Epstein, published by Encounter Books. Copyright © 2023 by Edward Jay Epstein. Reprinted by permission of Encounter Books.