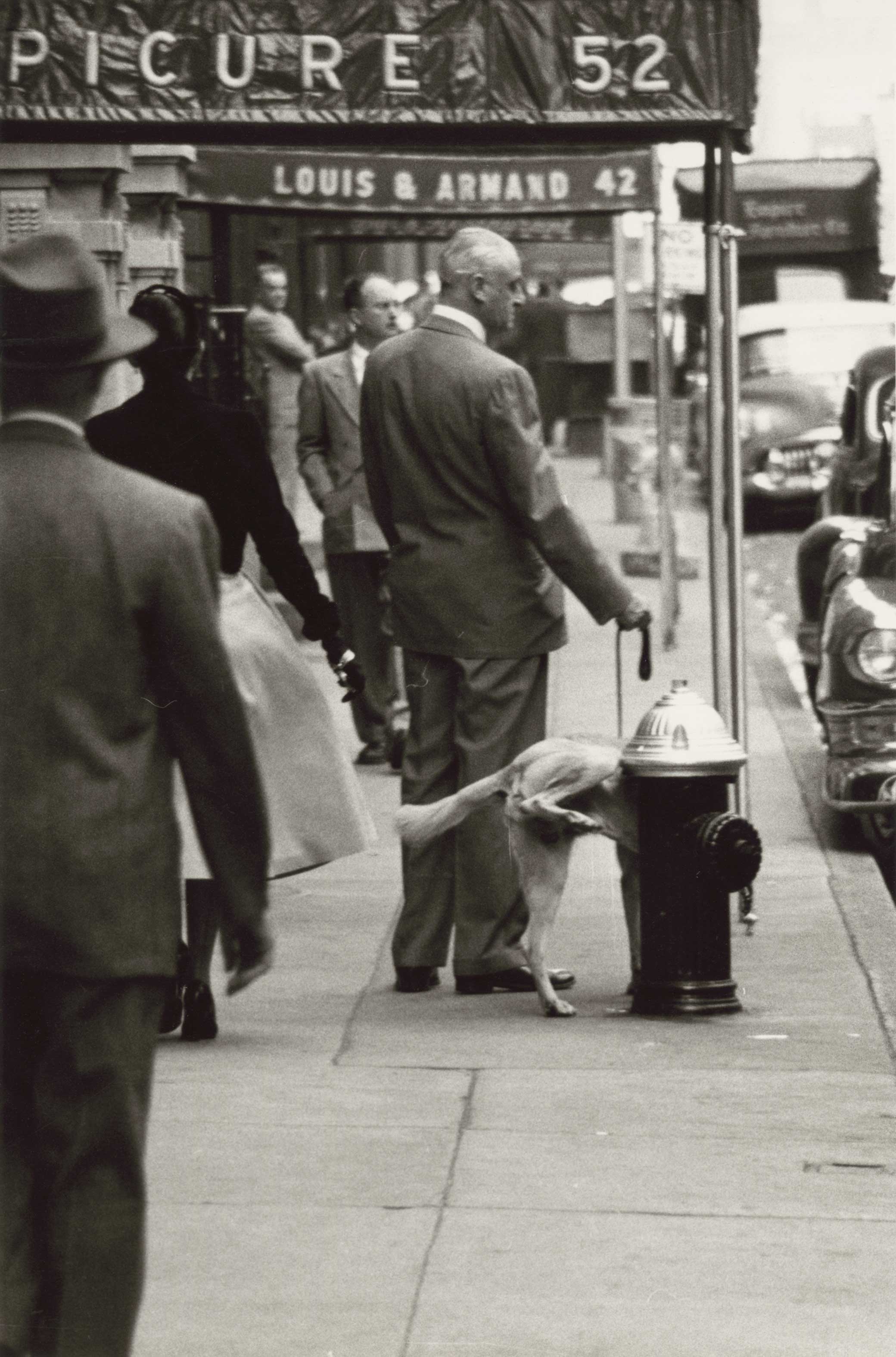

Man standing on sidewalk with a dog, 1953. Photograph by Angelo Rizzuto. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

Dog mess once had medicinal uses. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, physicians used it as an astringent in the form of album Graecum (dried and whitened canine excrement). Noting physicians’ additional use of album Graecum as an antiseptic, the Encyclopaedia Britannica of 1797 described its potent powers. It was so “putrid” that it could “destroy almost every vegetable or animal substance.” Some physicians even recommended it for sore throats. In 1899 physician W.T. Fernie quoted Richard Boyle’s advice from 1696 that “a homely but experienced medicine for a sore throat [is] to take about one drachm of album Graecum, or white dog’s turd, burnt to perfect whiteness, and with about one ounce of honey of roses or clarify’d honey make thereof a Linctus to be very slowly let down the throat.” But by the 1920s, dog mess had morphed from a marginal medicinal substance into a repulsive hazard to public health. It was “particularly disgusting and objectionable,” according to a British Home Office civil servant. As human defecation became increasingly private with the spread of lockable toilet and privy doors, and as roads and pavements became cleaner, physicians, public hygienists, journalists, councillors, and middle-class citizens identified canine “visiting cards” as a threat to public health and decency.

While middle-class dog owners, egged on by dog-care experts and dog-food companies, paid ever more attention to what went into their dogs’ stomachs, their indifference to where food waste was expelled from their pets’ anuses sparked frustration and consternation. Disgust—and the anger and fear that accompanied it—at dogs’ daily soiling of pavements and sidewalks led to campaigns to remove dog mess from London, New York, and Paris. Middle-class feelings of disgust informed these efforts, even though middle-class dog owners were often identified as the main culprits in allowing their dogs to foul.

Dog mess was deemed disgusting because it stank, polluted city streets, and contaminated bodies. It therefore required regulation. New knowledge about parasites coupled with feelings of disgust to propel public health officials, councillors, journalists, and voluntary groups to launch antifouling campaigns with varying degrees of success. But the continued fouling of streets provided stinking evidence that many dog owners met with indifference the feelings of disgust provoked by their pet’s excrement. Yet behind this insouciant stance lay an unspoken sense of revulsion at canine feces that prevented owners from picking up their own dog’s waste.

Hygiene became a central pillar of responsible modern dog ownership. Dog owners were charged with an ever-growing list of responsibilities. Outside the home, they had to distance their pet from filth. The training-manual authors Pathfinder and Hugh Dalziel called on owners to stop their dogs from eating rubbish and rotting meat off the streets and rolling in dirt. These activities were bad for the dogs and distasteful for human bystanders. At home, owners had to observe their dogs closely for signs of disease and parasites (not least fleas, lice, and worms) and keep them clean. According to scholar Alfred Barbou, “forgetfulness, negligence, and inobservance” of hygienic “rules” on the dog owner’s part would disturb the “balance” of a dog’s “physiological functions,” leading to disease. Ernest Leroy went so far as to claim that three-quarters of illnesses in dogs were caused by poor hygiene.

Sound hygiene would not just benefit dogs: it would also prevent diseases from spreading to humans. For dogs could pose a threat to health within the home. An 1895 medical report on Paris’s 14th arrondissement blamed diphtheria cases on the cohabitation of humans and dogs in residential buildings, and it called for “the elimination of all these useless animals.” If the overcrowded households of the urban poor and the intimate cohabitation of animals and humans in rural households had frequently concerned hygienists, pet dogs in any home—including the middle-class ones targeted by pet-keeping manuals—also constituted a risk. Owners had to make sure that their pets contributed to domestic cleanliness.

Many otherwise extensive dog-keeping manuals brushed past defecation, as if it were too abject a topic for their bourgeois readership. While some briefly discussed a dog’s necessity to go outside to meet their “intimate needs,” house-training tips likely were passed on by word of mouth instead.

A handful of authors avoided coyness and euphemisms to offer practical advice for preventing defecation from soiling the domestic environment. Some counseled their readers to provide their dog with a plate or box of sand, earth, or wood chippings in the home alongside taking it for regular walks. Young dogs, in addition, required housebreaking. H. Ducret-Baumann emphasized that owners must teach puppies (who are “subject to needs as imperial as they are natural”) that domestic carpets were not streets or grass. The house-trained adult dog was expected to relieve themself at set times during their walks. Those who failed to restrain themselves should be punished with a slap or whip on the hindquarters or side. Haynes agreed.

House-breaking was the “first lesson that has to be taught to the city dog.” The young dog needed to be taken out at regular intervals, and “should he offend, he ought to be punished at the scene of his crime” with a “smart slap under the jaw, accompanied by a word-scolding in a severe tone and uncompromising manner.” Theo Marples, editor of the weekly newspaper Our Dogs, recommended giving a “good skelping” to dogs caught “eas[ing] themselves” in the house. If the owner did not catch their pet in the act, they should rub the dog’s nose in it, presumably to generate feelings of disgust in the animal. Other experts prescribed less harsh disciplinary methods. Housebreaking was a necessary—if at times emotionally fraught—“ordeal.” But an owner’s anger and frustration at a puddle or stool on the kitchen floor would dissolve in the face of the offending dog’s sad eyes, according to James R. Kinney and Ann Honeycutt. They advised owners to carefully watch their dog and, should the animal begin to squat, quickly place their pet on a newspaper.

This was harder to anticipate with puppies than with older dogs, who “sniff around and circle around and practically telegraph ahead for reservations.” One dog they knew of reportedly was trained to press a buzzer under the dining-room table, summoning a servant to take the animal out. Unlike expert William Haynes, Kinney and Honeycutt advised against punishment and the “disgusting and antiquated method of ‘rubbing his nose in it.’ A self-respecting dog would be well within his rights if he pulled a knife on a person who did that to him.” They promised worried owners that one “holy day,” their dog would go to the newspaper voluntarily, which was “one of the prettiest sights in the world.”

Responsible dog owners needed to pay strict attention to what went into their dog’s mouth, but beyond making sure that their pet did not foul inside the home, little attention was paid to where the feces ended up outside domestic settings. Owners with yards and gardens had the easiest solution. Self-styled American dog psychologist Clarence E. Harbison counseled that dogs, especially bitches, could be easily house trained. Put them in the yard after meals or when it looked like they needed to defecate, he advised his readers. But for those owners without outdoor space, their dogs needed to relieve themselves off the premises. With experts underscoring the importance of walks to canine health, the street was framed as the main site of defecation for dogs. In this vein, Marples casually suggested that owners feed their dogs in the morning, then send them out onto the street to defecate in the afternoon. Dog-care experts like Marples presented streets as unproblematic places for canine defecation. But as streets became cleaner, this insouciant view was increasingly untenable.

It was hard for some observers to discuss the canine excrement that was now visible within the modern cityscape. In a letter to the Times of London, Bristol-based Dr. G. Knowles acknowledged the difficulty of discussing the foul matter: “I can only think that people have been comparatively silent regarding this disgusting nuisance out of a sense of delicacy.”

Euphemistic language, a common way to distance oneself from excrement in the modern West, came to the fore. In this vein, the chair of the Committee on Parks of the Women’s Municipal League, a New York association dedicated to promoting personal and public hygiene, complained somewhat cryptically about dogs “loiter[ing]” on the sidewalk rather than being led to the street by their owner, whose inconsideration prevented the sidewalk from being kept in a “decent” state. Those who could bring themselves to mention the unmentionable struggled to describe the scale of the problem. New York’s streets and stoops were “filthy beyond expression,” wrote one New York Times reader.

But a language of disgust did emerge to express revulsion at canine excrement. In New York, defilement became a key term to describe dogs’ fouling of the pavement, one with strong moral overtones and connotations of corruption and desecration. It was not just paving slabs that were defiled but anything that happened to be on the streets. A New York Times reader noted how “one is often shocked and nauseated to see the defilement of ice, vegetables, flowers, &c. by dogs.” Canine excrement corrupted objects of life and beauty that would otherwise brighten up New York’s streets. It was “offensive” to see how dogs “defiled sidewalks, posts, steps, lampposts &c,” grumbled another reader of the paper. Dog mess sullied public and private property, and it insulted the sensibilities of all who saw themselves as defenders of “decency and cleanliness.” The soiling of the street furniture intended to improve the cityscape and affirm New York’s modernity weakened residents’ faith in progress. The top of the lamp post may have radiated light and civilization, but its base remained mired in waste and backwardness.

Parisians were the least coy when discussing dog mess. The term souillure (blemish) provided a way of speaking about canine excrement, suggesting it was a stain that needed to be wiped away. French physicians and public hygienists were struck by the diversity of dog feces. Dr. Marcel Clerc, a hygiene specialist at the Medical Faculty of Paris and member of the Society for Public, Industrial, and Social Hygiene, noted that it varied according to the particular dog’s “intestinal situation” and “atmospheric conditions.” Canine excrement ranged from the “dropping [crotte]” deposited by little dogs to the “human-sized fecal black pudding [boudin] of the police dog.” Writing in La presse médicale and taking a dig at wealthy dog owners, “Un piéton” (whom Clerc identified as city councillor Jacques Romazzotti) similarly contrasted the “marble”-sized excrement of the “marquise’s beloved little Pekingese” with the “enormous black pudding created by the industrialist’s wolfhound.”

But whatever its provenance and consistency, feces was a “disgusting spectacle” that made pavements “revolting” and turned them into “cesspits.” For Harley Street physician and suffragette Agnes Savill, the streets of London had similarly become a “vast latrine for dogs.” In all three cities, dog mess was an unwanted reminder of the city’s dirtier recent past. Dogs had become regrettable features of the modern city’s sensory landscape: “The presence of these animals is an offense to the senses of sight, smell, and hearing,” noted one New York Times reader (who was also aggrieved by all the barking).

Why did dog excrement seem so revolting? Clerc suggested that the similarities with human feces made it particularly “disgusting.” Moreover, discreet defecation had become a marker of refinement and self-discipline. Dog mess was an unwelcome and very public reminder of bodily functions. It became a filthy yet fascinating taboo in a culture “founded on the repudiation of bodily products.”

Excerpt reprinted with permission from Dogopolis: How Dogs and Humans Made Modern New York, London, and Paris by Chris Pearson, published by the University of Chicago Press. © 2021 by the University of Chicago Press. All rights reserved.