House, by Bill Traylor, c. 1940. Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts, Montgomery, Alabama, Gift of Charles and Eugenia Shannon.

In the late 1920s, Bill Traylor, a black man from rural Alabama, found himself at a crossroads, when he would leave behind one lifetime and embark on another. Then in his midseventies, he realized that his tethers to plantation life had fallen away, so he traveled, alone, into the urban landscape of Montgomery. In the segregated part of town, he found work and lived successively in several different places; he would spend the next twenty-plus years there, with one foot rooted in his agrarian past and one in the evolving world of African American urban culture. After being in Montgomery for about a decade, his physical strength waning, Traylor made the radical steps of taking up pencil and paintbrush and attesting to his existence and point of view.

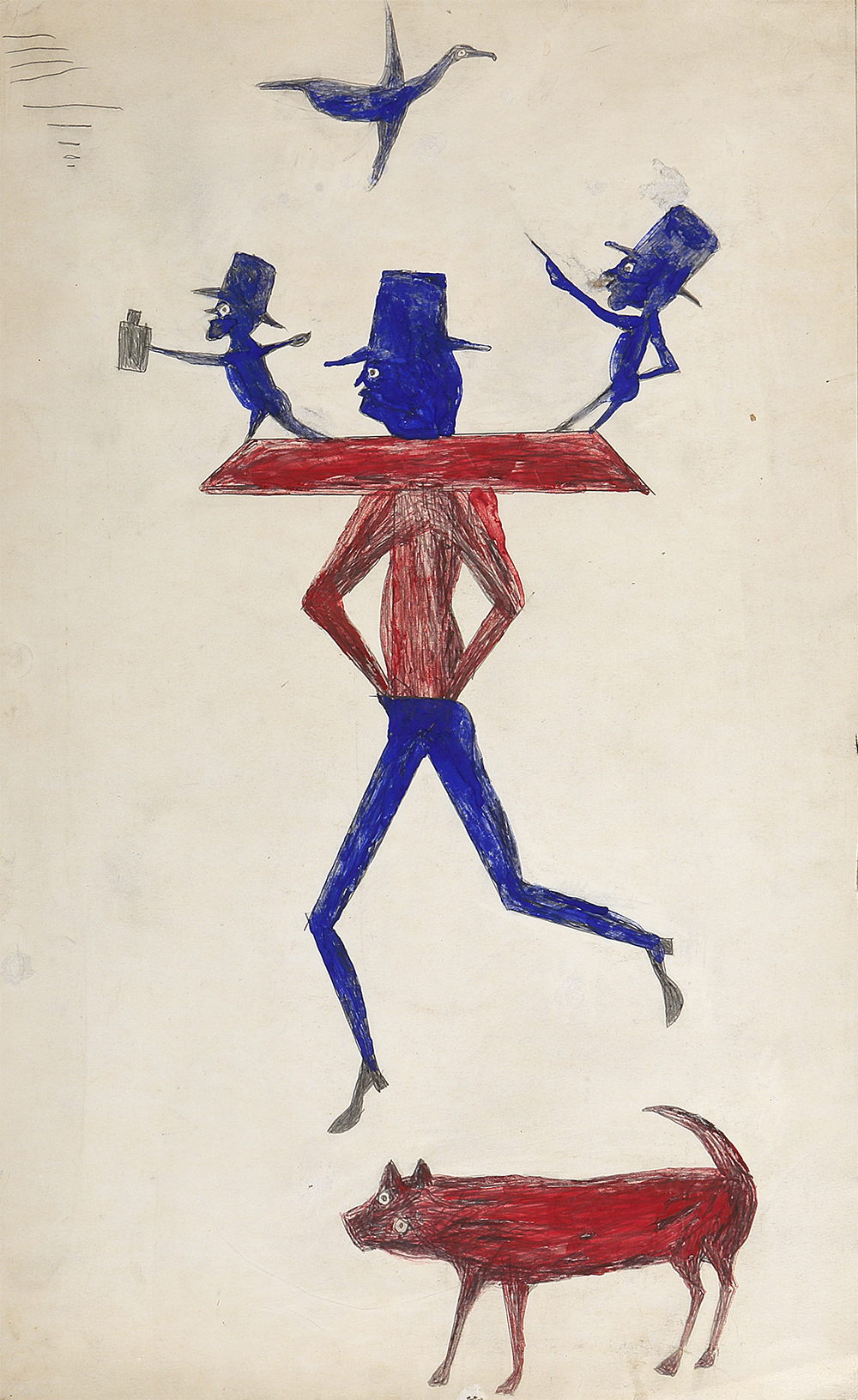

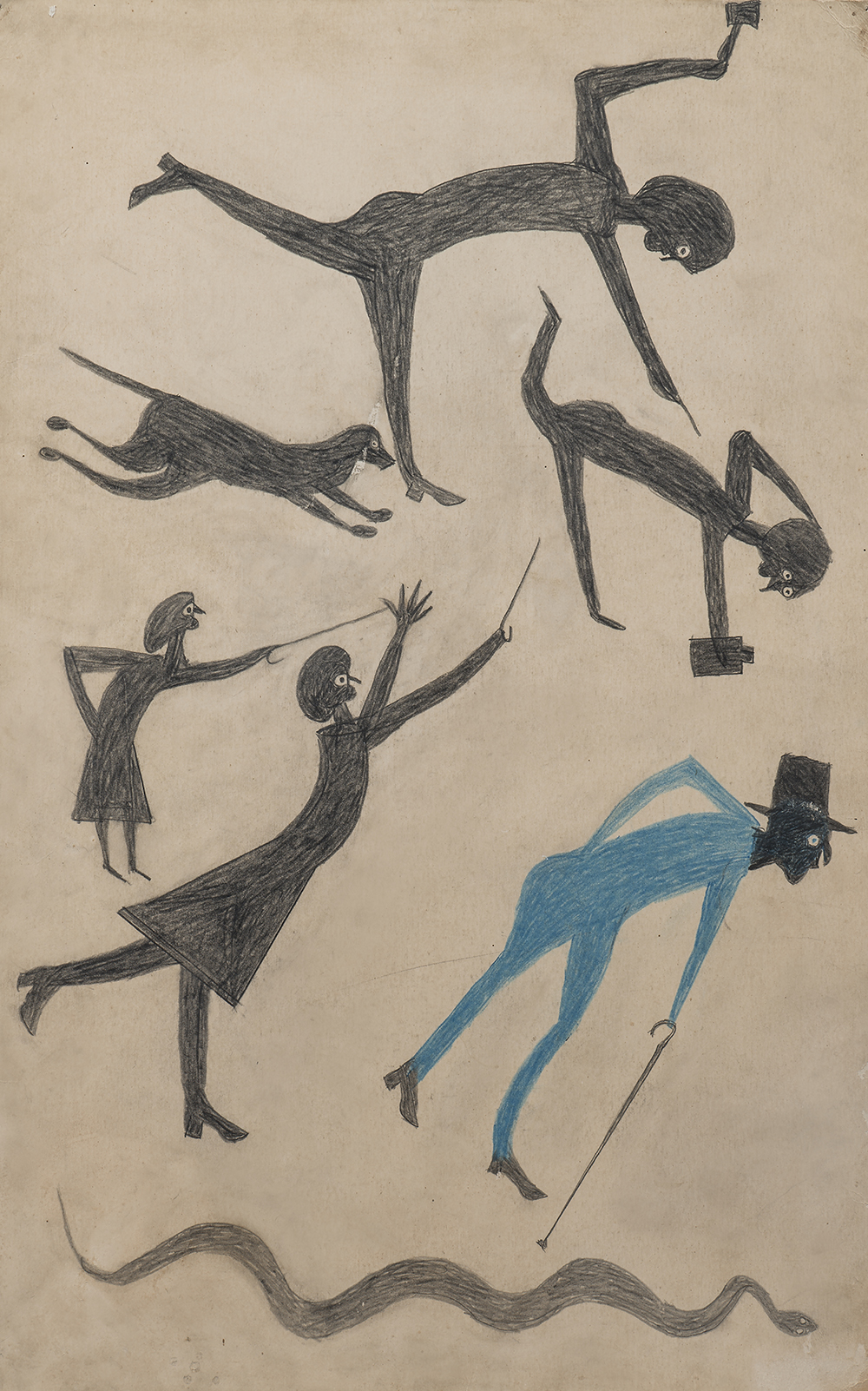

Sitting on a street corner minding his own business, Traylor was almost invisible, but his artwork, which was visually striking and politically assertive, eventually—posthumously—cast him as larger than life. He had no road map for his project, which he undertook in a time and place that entailed great risk. His scenes range from quotidian to edgy to bone-chilling: a woman and her child, a black person reading, a harrowing chase, a lynching.

Today Traylor is considered an American artist of renown, but that he became one at all was against the odds. His existence was almost equally divided between two centuries. He was a twentieth-century artist, known for his simple yet powerful distillations of tales and memories and brilliant use of color, but in important ways he remained a nineteenth-century man.

Bill Traylor was born into slavery around April 1, 1853, on the Alabama plantation of John Getson Traylor (then deceased) in Dallas County, near the towns of Pleasant Hill and Benton. In 1863, when Bill was about ten, he and his family were relocated from the farm of John G. Traylor to that of John’s brother, George Hartwell Traylor, whose plantation was just across the county line to the east, in Lowndes County, on what is now Double Church Road. When Emancipation became a reality in the South two years later, Bill and his family remained on George Traylor’s land as laborers.

Records indicate that Bill had three marriages, two legal and one common-law, occurring in 1880, 1891, and 1909. By 1910 he and his family (which would grow to include fifteen children from those compiled relationships) were living on the outskirts of Montgomery and working as tenant farmers. His third wife, Laura, died in the mid-1920s, after which, in 1927 or 1928, Bill moved to Montgomery. Except for brief stints with his grown children in Detroit, Philadelphia, and Washington, DC, before and during World War II, he remained in Montgomery until his death on October 23, 1949. These are the skeletal facts of his life.

The art world’s discovery of Traylor has often overshadowed the details of his personal journey for two reasons. The first involves Charles Shannon, a prominent white artist from Montgomery who met Traylor in 1939 and began to collect and save his work; without that key encounter, Traylor and his art likely would not have gained any recognition. But the circumstances also placed the story entirely in the hands of the empowered teller rather than those of the man whose life it was. Dovetailing with this unequivocally skewed influence is the second fact that Traylor’s own narrative is difficult to trace with any accuracy, and romantic myths easily filled the vacuum.

In his late years, Traylor put down a lifetime of memories, dreams, stories, and scenes. The body of his extant work, which he made in just four years, between 1939 and 1942, was internally driven and formed organically. His images are steeped in a life of folkways: storytelling, singing, local healing, and survival. They look freedom in the eye but don’t fail to note the treacherous road African Americans had to travel along the way. Traylor’s pencil drawings evidence a learning process that spanned rudimentary mark making and a sophisticated reduction of form, color, and gesture. They show the artist’s attentive observation and incisive ability to convey mood and action. Determined to shape a visual language for and by himself, Traylor became a master of freeze-frame animation and condensed complexity. His pictures comprise an oral history recorded in the only language available to an illiterate man—a pictorial one. Although people would purchase drawings from him for a dime or a quarter, he did not make them to please anyone else’s taste or with anyone’s guidance.

Unsurprisingly, Traylor’s visual depictions echo the beliefs and stories that had carried his people’s history from slavery through many subsequent decades. As these modes of expression are well known to do, Traylor’s imagery often holds veiled meanings and lessons underneath the veneer of simplicity or hilarity. Traylor experimented with abstraction and became adept at using it. He would have understood acutely that faithful representation could be perilous for a black man to pursue; his art reveals the various ways in which he skirted clarity and mitigated risk.

Traylor’s penciled and painted depictions confront us with not only the humanity of the artist but also the world beyond the personal; his is an eyewitness account of the American experience at a time when black people were supposedly free yet rarely had any control over their own lives. Traylor’s work is unique in media, size, scope, place, and era. Aside from the historical and cultural ways in which his art is vitally important, it is also endlessly astonishing, bold, and enigmatic. When Traylor died in 1949, he left behind more than a thousand works.

Regrettably, a dearth of accurate information about lineage and family history is an inherent reality for African Americans born before the twentieth century. Important papers are either scarce or missing entirely, and those that exist (often handwritten) are factually inconsistent and difficult to read. Literacy was viewed as incompatible with the institution of slavery. Even long after emancipation, the ability to read and write was considered a sign of status, and whites, who too often regarded black people as inferior, made and kept the important civic documents for blacks without much concern for their accuracy. The result is that any investigation of extant records will frustrate attempts to chart a clear trail of facts. Traylor’s contemporaries provided important details about the artist and his art, but they also generated lasting misinformation and paternalistic views. Scholars and writers in more recent decades have variously contributed excellent and erroneous parts to a blended narrative that has become ingrained in the public mind.

Traylor was just a boy when the Union won the Civil War and the enslaved were declared to be free Americans. His parents were enslaved people, and Bill and his siblings were born into that heartless system and managed as property during their childhood years. Traylor’s experience was rooted in knowing the difference between the white and black worlds and keeping personal thoughts and views hidden. He was part of the first generation of blacks to become American citizens, a group that has often been eclipsed by the bracketing histories of slavery and civil rights. The historian and activist W.E.B. Du Bois noted that being an African American in the early twentieth century meant having a conflicting sense of self, with an ever-increasing desire to reveal a long-suppressed identity. “It is a peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity. One ever feels his two-ness—an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.” Du Bois describes the ineluctable desire to merge the two selves into one, without losing either of the “older selves.”

Citizens or not, freedom was not going to come easily. The backlash against emancipation was harsh. Lowndes County, where Traylor and his family spent much of their lives, had the reputation of being one of the South’s most brutal places. The social systems for keeping blacks impoverished and disenfranchised were forceful and pervasive. Traylor spent almost all his working years amid a culture that overtly preferred blacks to be illiterate and submissive, automatically accept accounting records that never seemed to come out in their favor, and toil endlessly on land that belonged to someone else, all while living in extreme poverty, without adequate nutrition or health care, and with the unremitting fear of wondering what comes next.

But it was also a time when things were percolating. Black schools were becoming prevalent, and programs for land ownership established. Musical forms that began as the folkways of the fields were urbanizing and growing popular. Many African Americans were gaining prominence as writers, scholars, artists, and agents of social change. Traylor would not live to see the civil rights movement, but he was among those who laid its foundation.

In the late 1930s, when Traylor was in his late eighties, homeless and in fragile health in Montgomery, he began to draw and paint memories of plantation life and images of an emerging African American culture in an urban setting. Yet his works are neither straightforward “memory paintings” nor realistic scenes from life. In fact, Traylor was a careful editor; he chose his subjects with specificity and omitted a great deal. His pictures are complex translations of oral culture that are best understood against the backdrop of the time, place, culture, and shifting societal views in which they were created. Traylor’s compelling imagery narrates the crossroads of radically different worlds: rural and urban, black and white, old and new.

Reprinted with permission from Between Worlds: The Art of Bill Traylor by Leslie Umberger, published by the Smithsonian American Art Museum in association with Princeton University Press. The book accompanies the exhibition of the same title, on view at the Smithsonian American Art Museum from September 28, 2018, through March 17, 2019.