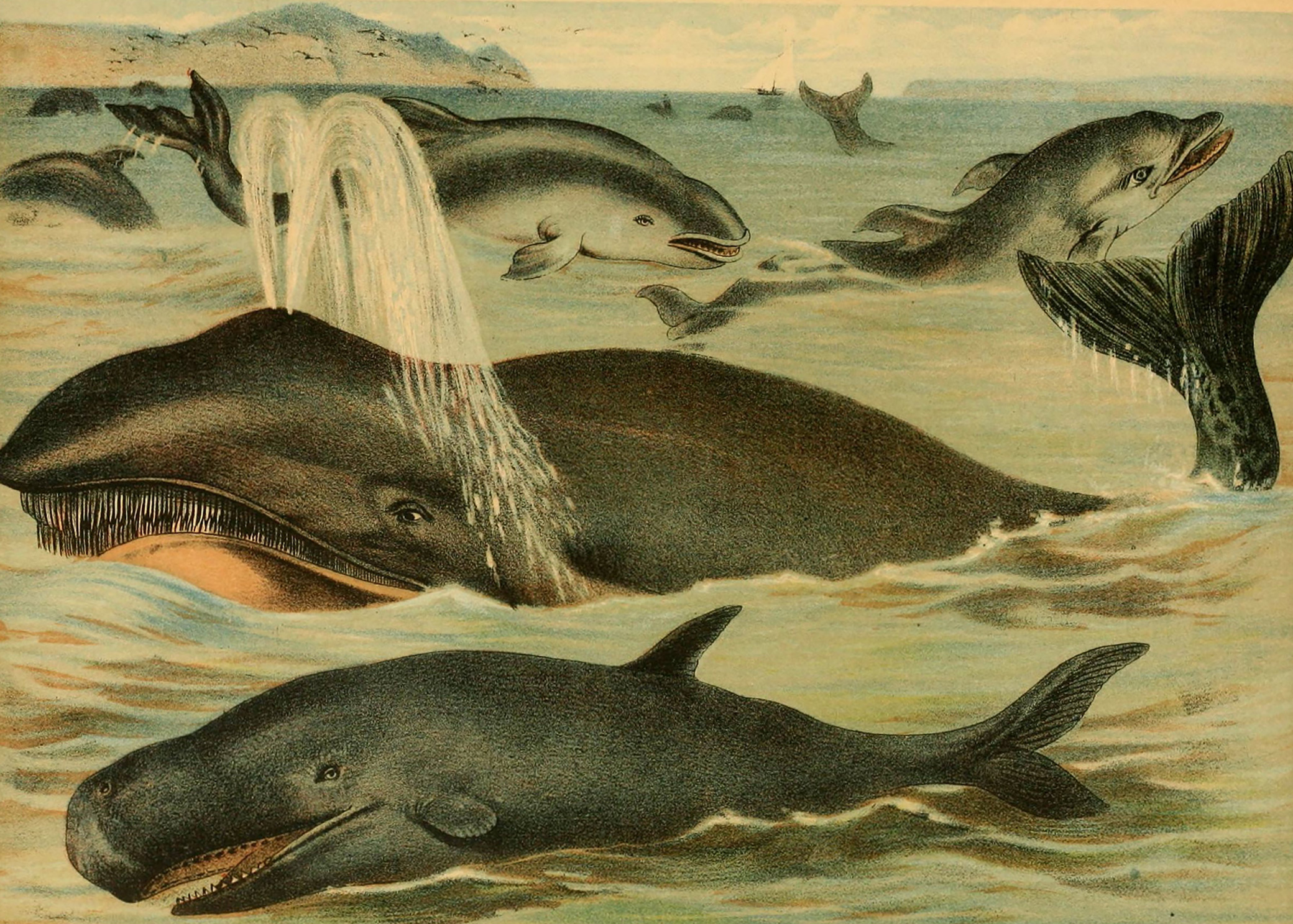

Cetacea, from The animal kingdom; based upon the writings of the eminent naturalists, 1897. Flickr, Biodiversity Heritage Library.

“In the early twenty-first century, we live in times as dark as those lived in by Melville in the nineteenth century and by Mumford in the twentieth,” Lewis Lapham observed when speaking to Aaron Sachs about Up from the Depths: Herman Melville, Lewis Mumford, and Rediscovery in Dark Times in an August 2022 episode of The World in Time. Sachs’ book recounts the story of Lewis Mumford, a survivor of the first World War, historian, and leading figure in the revival that cemented Melville’s reputation as America’s great tragedian. For Mumford, Moby Dick offered incontrovertible proof that the still-young country could produce literary masterworks. In their conversation, excerpted in our recent Herman Melville episode of The World in Time, Lapham and Sachs dwelt on the chapter of Up from the Depths, excerpted here, in which Sachs and Mumford both examine the conflicting, dialectical threads that Herman Melville wove on his cetological loom.

Though the occasional notice, between November 1851 and February 1852, hailed Moby Dick as a brilliantly original masterpiece, the majority of the reviews bestowed on it such labels as “tiresome,” or “shockingly irreverent,” or just “strange.” To Melville, it must have felt like butchery and torture.

The most influential reviewers condemned the book as “an ill-compounded mixture of romance and fact,” its storyline constantly interrupted by “ravings and scraps of useful knowledge flung together salad-wise.” The simple tale of a wild, wayward whale hunt could have made for a successful novel. Or, alternatively, the author could have produced a definitive, comprehensive handbook about whales and whaling, leaving aside the “phantasmal” plot and utterly unbelievable characters, the “attempted description of what is impossible in nature and without probability in art.” What could not be tolerated, in the era of clear-cut, modern Progress, was any sort of hash or hedging, any monstrous hybridity, any confusion or ambiguity. It made no sense to interweave a weird, extravagant whaling narrative with a semester’s worth of cetology.

But that interweaving was at the heart of Melville’s purpose. Moby Dick thrums with images of looms, with the offsetting forces of warp and woof. The book threads together not just fiction and fact, not just past and present, not just storms and calms, but fate and free will, submission and defiance, culture and nature, doubt and faith, “civilization” and “savagery,” grief and good cheer, chaos and order, land and sea, darkness and light (amid all these binaries, the tension between male and female is conspicuously absent).

Sometimes the weaving is the kind that human beings have been doing for millennia, as in the chapter called “The Mat-Maker,” which shows Ishmael and Queequeg silently working together, not spinning yarns but threading them together, in rhythm with the gently lapping waves, as an “incantation of revery” seemed to hover over the ship. At other times, Melville invoked the modern looms he had seen in Northeastern textile mills, where all “spoken words” became “inaudible among the flying spindles.” Regardless, the weaving together of opposites took on thick, hempen meanings: “There lay the fixed threads of the warp subject to but one single, ever returning, unchanging vibration, and that vibration merely enough to admit of the crosswise interblending of other threads with its own. This warp seemed necessity; and here, thought I, with my own hand I ply my own shuttle and weave my own destiny into these unalterable threads.” Was this warp-and-woof construction a reflection of how Melville thought the world worked, or just an oversimplified conceit suggesting the limitations of human perception? Neither, and both. One point of all of Melville’s binaries is that, whenever you get caught up in a one-sided assumption—whenever you feel utterly constrained by fate or utterly sure of your free will—you’ll soon be shown the power of the opposite perspective. Offsetting forces are humbling.

Melville must have known that the unusual structure of his book would rattle his readers. Clearly, his contemporaries had little use for his defiance of expectations and conventions, for his questioning of categories, for his constant impulse to tack and jibe between genres. They would not have taken kindly to the chapters written as if they were scenes in a Shakespearean drama, nor the soliloquies that Ishmael could not possibly have overheard, nor the abstruse facts of natural history he could not possibly have known. So Melville must have been deeply committed to his chosen technique—as he hints, perhaps, in the Sunday sermon that the old whaleman Father Mapple delivers before the Pequod has left her port. “Woe to him who seeks to please rather than to appall,” says the preacher, condemning Jonah for being unwilling to utter “unwelcome truths in the ears of a wicked Nineveh.” On the other hand, “Delight is to him—a far, far upward, and inward delight—who against the proud gods and commodores of this earth, ever stands forth his own inexorable self.”

One of the reasons Moby Dick seems so modern in comparison to, say, Hawthorne’s novels is that its unpredictable swerves appear to offer a glimpse of the ever-shifting contradictions inside Melville’s inexorable mind. For a time, perhaps, he saw the Whale purely in symbolic terms, as embodying fate, or power, or evil, or the world’s indifference to humanity. But almost instantaneously the thought came to him that the Whale was also meaningful as a living being with certain physical characteristics and habits and relationships. Then he realized that the Whale also lit the world’s drawing rooms, and influenced the arts, and spurred adventures. Do you want to understand the world? No single narrative or perspective will ever steer you right.

Yet each new perspective could add something to the others. Modern science mattered as much to Melville as poetry. How could you write about whales without consulting the most recent volumes of natural history? When it came time to draft the chapter called “Cetology,” though, Melville realized that science was not quite as clear-cut as he had imagined, for the natural historians, having learned that whales possessed warm blood and lungs, were not even sure anymore “whether a whale be a fish.” Indeed, the proliferation of facts, based on empirical observation; the increasingly narrow specialization of experts; the commitment to systematized knowledge—all these modern developments had seemingly made it harder, not easier, to tear away the “impenetrable veil covering our knowledge of the cetacea.”

Melville did his winking best to provide a thorough classification schema, based on the one used by book publishers to distinguish the different sizes of their volumes: thus, Folio whales, Octavo whales, and Duodecimo whales. He also kept apologizing, though, for his “endless subdivisions based upon the most inconclusive differences,” which made for a “repellingly intricate” system, and which perhaps lent his chapter a dangerous aura of comprehensiveness: “any human thing supposed to be complete, must for that very reason infallibly be faulty.” The whole chapter is, in truth, a testament to his scientific inclinations, his desire to dissect reality. But Melville felt ambivalent about almost all of his inclinations. After a dozen pages, he threw up his hands: “God keep me from ever completing anything. This whole book is but a draught—nay, but the draught of a draught. Oh, Time, Strength, Cash, and Patience!”

Science returns again and again in Moby Dick, usually in the guise of modern progress, and usually serving to stall the actual progress of the narrative. Melville luxuriated in the undulation he was creating between drama and tranquility, motion and stillness, as he shifted between his increasingly desperate story and his research-based meditations on that story: “fact and fancy, half-way meeting, interpenetrate, and form one seamless whole.” In a sense, Melville had latched onto the radical, Romantic conception of science popularized by the great naturalist Alexander von Humboldt, whose magnum opus, Cosmos, was enthralling the western world in the late 1840s. For Humboldt and his followers—who included not just natural historians but also such poets as Emerson, Thoreau, and Whitman—the pursuit of scientific truths, in Mumford’s words, “no longer [meant] a restriction, a dried-up quality, an incompleteness; it no longer [deified] the empirical and the practical at the expense of the ideal and the aesthetic: on the contrary, these qualities [were] now completely fused together, as an expression of life’s integrated totality.” Or, as Humboldt himself explained, the holistic depiction of Nature must balance rigorous observation with wild imagining: “In the first place, I have endeavored to present her in the pure objectiveness of external phenomena; and, secondly, as the reflection of the image impressed by the senses upon the inner man, that is, upon his ideas and feelings.”

That balancing, that interweaving, that aspiration to capture a unified whole, mattered much more to Melville than moving his plot forward. His critics’ attachment to straightforward narrative reflected an assumption that their countrymen would continue to march through time confidently, successfully, as pioneers, conquerors, masters. But Humboldtian science could have a critical, political edge, juxtaposing the humility of interconnection with the hubris of colonial advance. “Progress” always doubles back on itself; the future is interwoven with the past.

Melville wanted his readers to feel as though Moby Dick had always been lurking in the depths, and always would be. Upon seeing the great skeletons of ancient leviathans, Melville himself was, “by a flood, borne back to that wondrous period...[when] the whole world was the whale’s I am horror-struck at this antemosaic, unsourced existence of the unspeakable terrors of the whale, which, having been before all time, must needs exist after all humane ages are over.” Today, in the age of climate change, scientists have started to suspect that warming oceans will pose a serious threat to many whales, especially the northernmost species. But Melville, whose apocalyptic imagination could keep pace with that of any twenty-first-century environmentalist, insisted that the cetaceans could never be overcome: “if ever the world is to be again flooded, like the Netherlands, to kill off its rats, then the eternal whale will still survive, and rearing upon the topmost crest of the equatorial flood, spout his frothed defiance to the skies.”

Ahab’s defiance, which drives all the action of the novel, may seem as timeless as the whale’s, but it is also meant to offset one specific malevolent act, the central trauma of his own personal past. Moby Dick took his leg; he must take Moby Dick’s life. What forces can offset trauma? Perhaps the old rituals of community—the solidarity of shared risk—a squeeze of the hand all around. Perhaps the embrace of difference—the transcendence of our inclination toward endless subdivision. Perhaps a breath of salt air, bright sun, the rolling of the ocean, the curve of a welcoming bay. Perhaps the recognition that we are all inevitably intertwined, each with the other, all with the world. Perhaps the adjustment of our “conceit of attainable felicity,” so that it’s not about recovery but rather “the heart, the bed, the table, the saddle, the fire-side, the country.” Captain Ahab, though, could no longer believe in the concrete joys of human existence. There could be no compensation, for him, but revenge. “Oh! how immaterial are all materials! What things real are there, but imponderable thoughts?...So far gone am I in the dark side of the earth, that its other side, the theoretic bright one, seems but uncertain twilight to me.”

Still, as Lewis Mumford understood, more deeply than many of his contemporaries, Ahab was not just a tragic figure. His defiance was also heroic, for we are all traumatized to some extent, and not to fight back against “the mystery of evil and the accidental malice of the universe” is to risk becoming the universe’s pawn. “Ahab is the spirit of man,” Mumford wrote, “small and feeble, but purposive, that pits its puniness...and its purpose against the black senselessness of power.” We humans may go humbly about our business—we may seek a simple life—“a happy marriage, livelihood, offspring, social companionship, and cheer”—and yet, regardless of our worthiness, we will eventually meet with “illness, accident, treachery, jealousy, vengefulness, dull frustration.” To Mumford, Moby Dick belonged at the heart of the Western canon, because ultimately all of Western history, “in mind and action, in the philosophy and art of the Greeks, in the organization and technique of the Romans, in the precise skills and unceasing spiritual quests of the modern man, is a tale of this effort to combat the whale—to ward off his blows, to counteract his aimless thrusts, to create a purpose that will offset the empty malice of Moby Dick.”

We offset meaninglessness through the construction of meaning. Ishmael may have been more skilled at interpretation than Ahab, but Ahab, an accomplished cetologist himself, who knew all there was to know about whales and simultaneously recognized their inscrutability, made a lasting contribution. Even as he lost faith in everything, he kept up his pursuit. “Without the belief in such a purpose,” as Mumford put it, “life is neither bearable nor significant: unless one is polarized by these central human energies and aims, one tends to become absorbed in Moby Dick himself, and becoming part of his being, can only maim, slay, butcher.”

The problem with Ahab’s approach was that he armed himself “with power instead of love.” Against the brute force of Moby Dick, he consolidated the forces of modernity, turning his men into machinery, his ship into a steaming engine of vengeance—“as if from the open field a brick-kiln were transported to her planks.”

Ahab merely provided the instigating motion. “’Twas not so hard a task,” he muses. “I thought to find one stubborn, at the least; but my one cogged circle fits into all their various wheels, and they revolve.” He is satisfied, and yet also a little disappointed. “D’ye feel brave men, brave?” he asks, once they’ve finally found Moby Dick.

“‘As fearless fire,’ cried Stubb.

‘“And as mechanical,’ muttered Ahab.”

It’s as if, in Mumford’s words, Ahab recognized his own complicity in transforming whaling “from a brutal but glorious battle into a methodical, slightly banal industry.” His men have become mere tools, to him; he can’t maintain his respect for them once they have coupled themselves to his locomotive. “The permanent constitutional condition of the manufactured man, thought Ahab, is sordidness.” Even his own passion could be understood as mechanical: “the path to my fixed purpose is laid with iron rails, whereon my soul is grooved to run.” By the story’s climax, Ahab has acquired so much momentum that he himself resembles “the mighty iron Leviathan of the modern railway,” and he seems to negate all the old, traditional offsetting forces of the world: “Alike, joy and sorrow, hope and fear, seemed ground to finest dust, and powdered, for the time, in the clamped mortar of Ahab’s iron soul. Like machines, [the crew] dumbly moved about the deck, ever conscious that the old man’s despot eye was on them.”

Ahab’s purpose was higher than that of the Pequod’s owners, who believed only in profit and comfort and “sluggish routine,” but his turn toward modernity, his exclusive embrace of the future, was also his death wish. Moby Dick is a tragedy—in part, the tragedy of American society as a runaway train. Ahab dies when his own harpoon line catches him around the neck as it’s being violently unspooled, with a sound like “the manifold whizzings of a steam-engine in full play.”

Yet Melville had found a new, compelling form for his tragic tale, one that balanced modern fluidity with ancient steadfastness. The mere survival of a lone sailor, Ishmael, spinner and interweaver of yarns, offered a measure of redemption. Through the act of storytelling, as Mumford argued, Melville had “conquered the white whale in his own consciousness: instead of blankness there was significance, instead of aimless energy there was purpose, and instead of random living there was Life. The universe is inscrutable, unfathomable, malicious, so—like the white whale and his element. Art in the broad sense of all humanizing effort is man’s answer to this condition: for it is the means by which he circumvents or postpones his doom, and bravely meets his tragic destiny. Not tame and gentle bliss, but disaster, heroically encountered, is man’s true happy ending.”

Melville never faltered in the belief that in confronting his white whale he had pushed his art as far as it could go—and so he struggled in confronting his scornful reviewers. As usual, his emotional condition in early 1852 is almost impossible to determine, but there are signs of dismay, and Mumford posited that he must have been “exhausted and overwrought.” Regardless of the reviews, Mumford thought, the effort of writing Moby Dick would have left the author in a state of “irritation, debility, impotence.” Of course, it’s again possible that Mumford was projecting: surely Melville’s experience composing his magnum opus must have run parallel to his own experience composing his Melville biography. Here was a Cape Horn in Melville’s life, Mumford insisted, a “crisis” that “almost unseated him,” as he “first became aware of the riled depths of his unconscious.” Certainly, the accomplishment had been supreme: “a new integration of thought, a widening of the fringe of consciousness, a deepening of insight, through which the modern vision of life will finally be embodied.” But the price had been steep, and few readers appreciated his long, drawn-out plunge into the depths.

Mumford, at least, would always be grateful. Moby Dick, for him, was a fully modernist questioning of modernity. It looked both backward and forward; it embraced science but also critiqued science; it told a classic adventure story but interrupted itself to take stock of the writer’s inner world.

In 1952, after completing the final volume in The Renewal of Life, Mumford was musing on the style he had developed for the series, and his mind immediately jumped back to Melville. His approach in all four books, he said, was modeled on a “new kind of writing that grew up first in the nineteenth century: a species represented by Moby Dick and by William James’s Psychology, in which the imaginative and the subjective part is counterbalanced by an equal interest in the objective, the external, the scientifically apprehended.” He thought his prose was marked by a strong inner voice, but what he ultimately strove for was a “combination of personality and individuality with impersonality and collective research.”

Everyone needs to be checked and balanced, in a modern democracy, or else the captains, like master sprockets, might wield too much power. “Cursed be that mortal inter-indebtedness,” Ahab exclaims. But the power of the interdependent collective was one of the key lessons of Melvillean cetology. Moby Dick, it’s true, swam forth his own inexorable self; perhaps he was immortal, indestructible. The survival of cetaceans, though, especially in the age of empire, depended on their banding together in great armadas, “as if numerous nations of them had sworn solemn league and covenant for mutual assistance and protection.” Mortal inter-indebtedness was timeless; what modernity demanded was a new, deliberate interweaving.

From Up from the Depths: Herman Melville, Lewis Mumford, and Rediscovery in Dark Times. Copyright © 2022 by Aaron Sachs. Published by Princeton University Press. Reprinted by permission of the author.