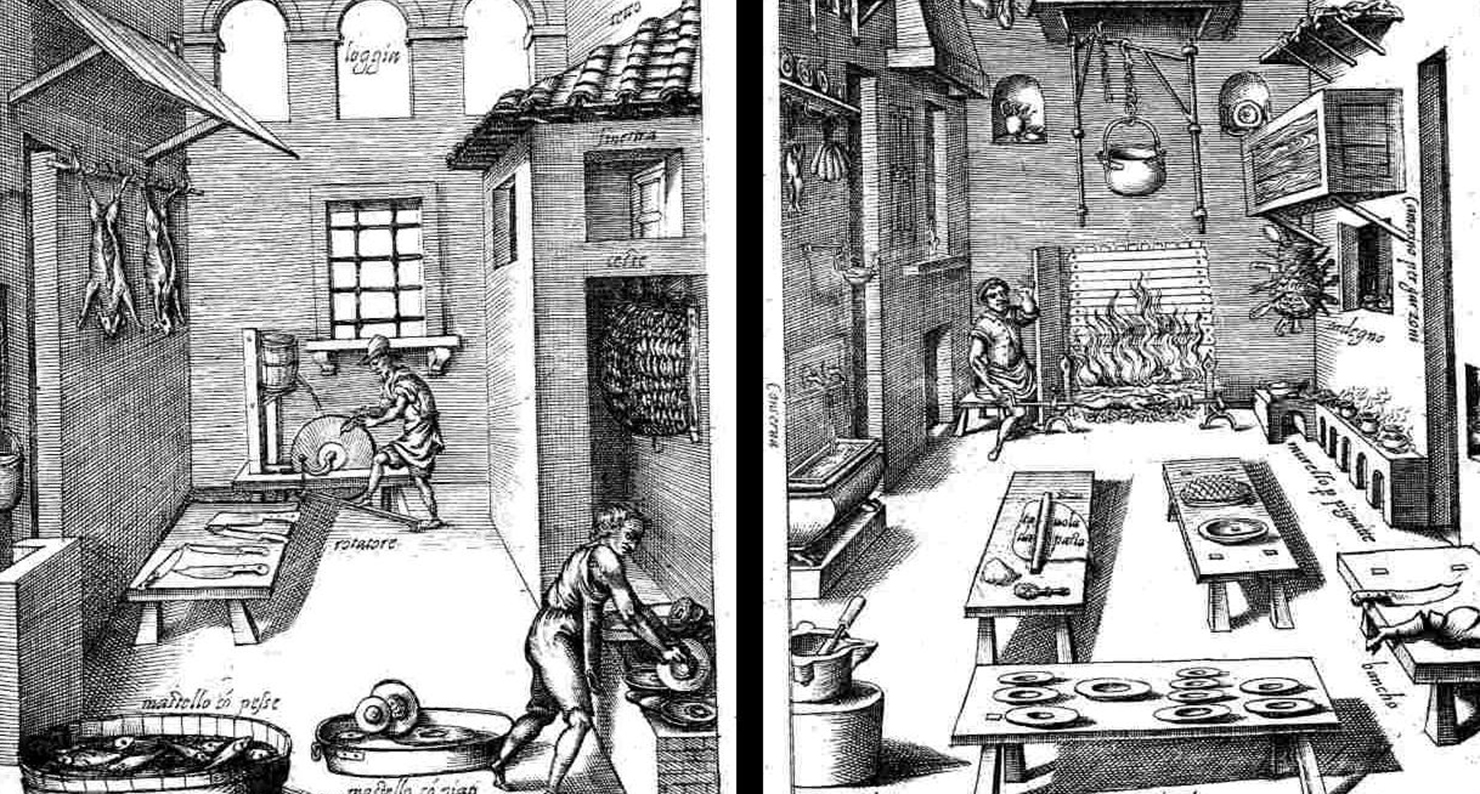

Interior of a Renaissance kitchen, illustrations from Opera di M. Bartolomeo Scappi, 1570. Image courtesy Paul K.

They called him “fat boy,” this seventeen-year old apprentice in the studio of Florentine painter Verrocchio who would receive care packages from his step-father, a pastry chef. The bastard son of a Florentine notary and a lady of Vinci, the boy’s doting step-father gave him a taste for marzipans and sugars from a very young age. The apprentice would receive the packages and devour them so quickly—crapulando, it was called, or guzzling—that the master felt the need to punish him, instructing the boy to paint an angel in the corner of a baptism of Christ, a mediocre painting which hangs in the Uffizi because it includes the first work of Leonardo da Vinci.

After three years as an apprentice, twenty-year old Leonardo took a job as a cook at the Tavern of the Three Snails near the Ponte Vecchio, working during the day on the few commissions his master sent his way and slinging polenta in the evenings. Polenta was the restaurant’s signature dish, a tasteless hash of meats and corn porridge. The other cooks at the Three Snails cared little about the quality of the food they served, and when in the spring of 1473, a poisoning sickened and killed the majority of the cooking staff of the tavern, Leonardo was put in charge of the kitchen. He changed the menu completely, serving up delicate portions of carved polenta arranged beautifully on the plate. However, like most tavern clientele, the patrons preferred their meals in huge messy portions. Upset with the change in management, they ran Leonardo out of a job.

Much like a modern struggling artist, Leonardo da Vinci was in his daily life a line cook, tavern keeper, and chef-for-hire. “My painting and my sculpture will stand comparison with that of any other artist,” he wrote in a humble introduction to Ludovico Sforza, the future Duke of Milan, by way of a job application. “I am supreme at telling riddles and tying knots. And I make cakes that are without compare.”

Sforza took him on neither as a cook, painter, or sculptor, but instead as a lute player and after-dinner entertainer. Leonardo attempted to show his lord his new inventions for fortifications, catapults, and ladders, but Sforza paid little attention until the lute-player fashioned his inventions out of marzipan and jelly. Sforza charged the young man with refurbishing his kitchen, a task which would consume the life of Leonardo and the entire Sforza court.

Five hundred years before Modernist Cuisine’s exhaustive look at molecular gastronomy, The Kitchen Notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci envisioned a culinary world as studio and laboratory, where food was to be prepared efficiently, beautifully, and ingeniously. Unfortunately, Italian food of the late fifteenth century had less to do with the luxurious feats of Ancient Rome and more to do with the rustic tastes of the Goths, whose dishes included meats and birds for those who could afford it, and an endless parade of porridge and gruel for those who could not. Leonardo was horrified by much of the food that was served to him, both at court and at home, and he included in his notebooks a running list of dishes that he hated, but that his own servant insisted on serving him: jellied goat, hemp bread, white mosquito pudding, inedible turnips, and eel balls—which he notes, “this dish if eaten often can cause madness.”

The notebooks, which include a history of Leonardo’s tenure as chef at the Sforza court, is primarily a collection of recipes (cabbage jam, snail soup), wayward thoughts (“Would porridge balls in gold-leaf attract My Lord’s attention?”), dining etiquette (“On the Unseemly Behaviors at My Lord’s Table”), household tips, (“On Ridding your Kitchens of Pestilential Flies”), and household inventions (“The Machines I Have Yet to Design for my Kitchen”).

For Leonardo, every food was only as good as the machine that created it, the technique was as important as the taste. Leonardo’s work in the Sforza kitchen strove for efficiency, but often the result of all this time-saving was sheer insanity, reported the humanist courtier Sabba da Castiglione:

Master Leonardo da Vinci’s kitchen is a bedlam...At one end of the premise, a great waterwheel, driven by a raging waterfall over it, spewed and spattered forth its waters over all who passed beneath and made the floor a lake. Giant bellows, each twelve feet long, were suspended from the ceilings, hissing and roaring with intent to clear the fire smoke, but all they did accomplish was to fan the flames to the detriment of all who needed to negotiate by the fires—so fierce the wandering flames that a constant stream of men with buckets was employed in trying to quell them, even though other waters spouted forth on all from every corner of the ceilings.

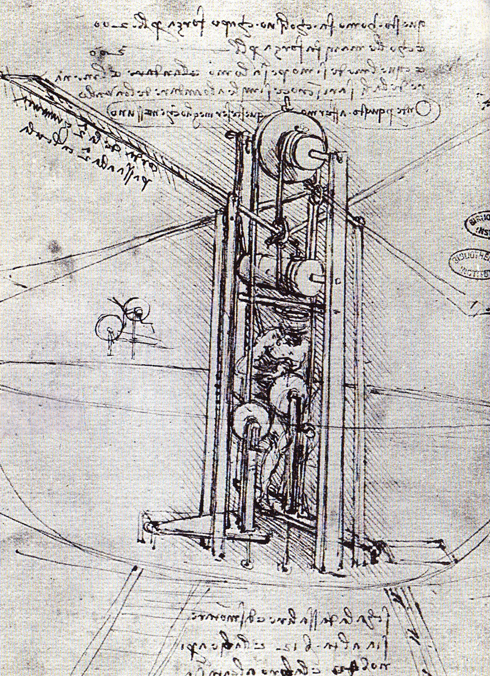

Every kitchen task could be mechanized—crushing garlic, pulling spaghetti, plucking ducks, cutting a pig into cubes—but the machines Leonardo imagined were sometimes far more elaborate than the task required. His invention for a giant whisk twice the size of a man involved an operator from within who was constantly in danger of being wisked into the sauce. (See below) Another model involved a team of three horses engaged in the task of crushing a nut.

The problem with these inventions was not that they could potentially kill anyone who used them, but instead that Leonardo was constantly frustrated with powering them. “But how shall I work them? By wind or by water? By cogs and by cranks? By oxen or by peasant-power?” One machine was intended to be operated by bees.

Leonardo was also a master of dining etiquette, possibly inventing the first napkin (and the first twenty-foot rotating napkin dryer) after Sforza insisted on “tethering beribboned rabbits to the chairs of his table guests, that they may wipe their grease-ridden hands on the beast’s backs.” Leonardo had strong opinions on the manners of the court, chiding the courtiers for bad behavior:

He should not place his head upon his plate to eat.

Neither should he sit beneath the table for any length of time.

He should not place unpleasing or half-chewed pieces of his own food upon his neighbor’s plate without first asking him.

He should not wipe his knife upon his neighbor’s clothing.

Nor use his knife to carve upon the table...

He should not set loose birds upon the table.

Not snakes nor beetles...

And if he is to vomit then he leaves the table.

Likewise if he is to urinate.

Leonardo’s notebooks also humorously reveal the hidden violence of the Sforza court. He included instructions for hiring a new taster after Sforza’s dies from a poisoning (“the old taster has done his job too well”). What Leonardo didn’t know at the time was that Sforza had his man killed in order to install an actual poisoner, hired to slowly kill his elder brother and assume the Dukedom. Death was a common pastime at the dinner table, and Leonardo included methods for removing blood from a table-cloth after a carving accident or assassination (“vigorous rubbing of warm sprout water”) without, of course, bothering the guests The possibility of an actual assassination was a real concern at the Sforza court, and Leonardo explained that there should be a refined protocol to the affair:

If there is an assassination planned for the meal, then it is seemliest that the assassin should be seated next to he who is to become the subject of his craft...as this will cause less interruption to the conversation if the action of the event is confined to one small area...After the corpse (and bloodstains if any) are removed by the serving persons, it is customary for the assassin also to withdraw from the table as this presence may sometimes be disturbing to the digestions of the persons who now find themselves seated next to him, and to this end a good host will always have a fresh guest, who has waited without, ready to join the table at this juncture