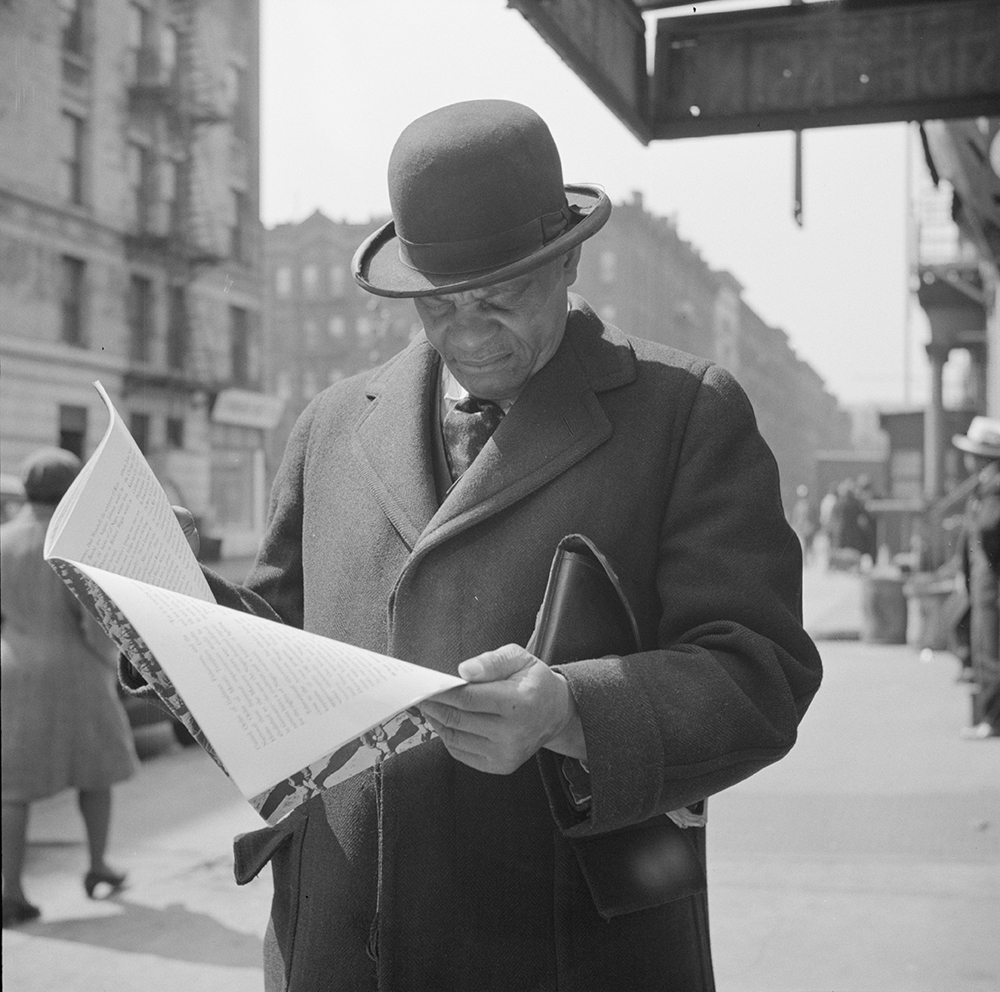

Gordon Parks reading Yank, the Army Weekly in the Office of War Information, 1943. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

Born in 1912, Gordon Roger Alexander Buchanan Parks was the youngest of fifteen children born to tenant farmers in Kansas. Frustrated by the limits to his education imposed by segregation, at age fourteen he dropped out of school, left home, and embarked on a decade of traveling between Minneapolis, Chicago, and New York; working odd jobs; and struggling to make ends meet.

Parks was among the many African American men in the United States employed in service jobs in the railway industry. From 1936 to 1938, he worked for the Northern Pacific Railway. A newly married man in his mid-twenties with a newborn son, Parks and his small family lived a meager life in Saint Paul, Minnesota. These circumstances motivated him to take a job as a dining car waiter on the North Coast Limited, which, because it traveled between Chicago and Seattle, allowed him to see his family in between runs. To say waiting tables was less than satisfying to him is a gross understatement. “I loathed the job,” he declared later, summing it up as “serving bigoted businessmen.” He could not have imagined upon taking the menial and demeaning job that it would launch him on a path to becoming one of America’s most famous photographers.

When he worked long runs from the Midwest to the West Coast and back again, he was ever looking for something to occupy his mind or, better yet, stir his imagination. While his coworkers slept and gambled in their downtime, he read magazines discarded by passengers. One day, he picked up an abandoned photomagazine and began to leaf through it. The magazine included a photo-essay about migrant workers. The series of grainy black-and-white photographs depicted impoverished agricultural workers who, displaced by economic disaster, dust storms, and floods, had taken to the road to find work and, along the way, sought shelter in shanties made of cardboard boxes. The photographs were products of the Farm Security Administration (FSA), which, during the latter 1930s, sent documentary photographers throughout the country to record the effects of the Depression on Americans. These images circulated through various channels, including popular magazines such as the one Parks stumbled on as a railroad worker.

Parks had a profound reaction to the FSA’s visualization of the Depression as portrayed through the life of migrant workers. He squirreled away the magazine that contained the photo-essay in his bunk and then took it home with him for repeated study. The photographs that so captivated him were the product of a moment when several dynamics merged in the 1930s to transform visual culture and politics in the United States.

By the time Parks encountered the FSA photo-essay on the train, visual imagery had become a common medium by which Americans received information. The camera, which had once been reserved for private or artistic use, had become a journalistic tool. News outfits increasingly relied on photographs to relate news, once advances in camera and printing technologies, and the advent of wire services and photo agencies, made it sensible (which primarily meant affordable) to do so. The interwar period experienced a “quantum leap in the proliferation and social dispersion of photographic images.” Every development in the history of photography provoked changes in U.S. culture and grand statements about those changes. What distinguished the post–World War I image culture? The difference was a changing hierarchy in which the image was overtaking the written word as the preeminent means for the exchange of ideas and information. The rise of photojournalism, especially, established seeing as the grounds for knowing. The aesthetic or artistic value of an image was no longer its primary characteristic or value: visual imagery was becoming the privileged unit of American thought.

The rise of an image-based informational culture compelled—as much as it reflected—changes in governing, a phenomenon quite visible in how the Roosevelt administration publicized different programs and instructed the public during the Depression. New Deal agencies relied heavily, even primarily, on imagery and altered the appearance of American public space. In the 1930s, for example, image-based posters created by the Works Progress Administration (WPA) proliferated as publicity for work programs, sanitation and nutrition practices, natural and urban attractions, and even the WPA itself.

No New Deal agency relied on images more than the FSA. Launched in 1935, the FSA photography project ran through 1944, the last two years as an OWI operation drafted to the production of war propaganda. During that time, the agency’s team of full-time and freelance photographers produced approximately 177,000 black-and-white and color photo images of American life during the Depression and World War II.

The FSA’s public relations successes lay in its use of documentary photography, which was, at the time, a preferred visual medium for the representation of “truth.” The defining aesthetic characteristic of documentary photographs was realism: rather than art or souvenir, their currency lay in their supposed veracity as images that mirrored a real-world referent at a particular moment. Moreover, the advent of portable cameras such as 35 mm models gave birth to “the man on the scene,” or photographers who encountered scenes in the world rather than staging them in the studio. Documentary photographs gave the look of a visual report captured by the camera’s eye through a mechanical process, rather than a vision manufactured by the camera’s human operator. The literal black-and-white composition of most Depression-era documentary photographs led to perceptions of the medium as an unambiguous and reliable representational form.

Parks’ first encounter with FSA photographs kept him “thinking, thinking, looking and looking.” The images of the nation’s dispossessed and displaced agricultural workers, he said, compelled “anyone with any feeling…to look and notice and…absorb the message that they were preaching.” As one of the more controversial New Deal initiatives, the FSA had to preach hard, and preach often. Conservative members of Congress, business leaders, contingents of the press, and members of the American middle class criticized the agency as socialist based on its relief programs for farmers and other agricultural workers. While they largely accepted Social Security as an entitlement program, many Americans viewed the FSA as dealing in handouts for a population of lazy or backward country folk.

The FSA’s propaganda convinced Parks of photography’s power as a tool of social commentary. In 1937, no longer satisfied by just looking, he bought his first camera during a stopover of the North Coast Limited in Seattle and began learning photography. Through strong self-promotion and the support of Marva Louis (wife to then-celebrated black boxer Joe Louis), Parks quickly gained a reputation and some business doing studio photography. By 1940, he was able to quit the railroad, and he and his wife, Sally, moved with their two small children from Saint Paul to Chicago’s South Side, where he quickly became the photographer of choice among the black elite and even “wealthy white sitters.”

Studio photography sustained Parks and his family, but the documentary form continued to hold and inspire his interest as a visual artist. He became a serious student of FSA photography, which he tracked through magazines and, especially, photo-texts. Photo-texts, which combined prose and documentary photographs, emerged as a popular trend in the late 1930s, a direct result of the rise of photo-magazines and New Deal agencies’ flooding of mainstream media with documentary imagery. As lengthy visual narratives, these commercial products were social commentaries advanced through carefully selected photographs captioned with great intention.

The photo-essay of migrant workers that Parks first viewed on the train was formulated to inform and inspire sympathy among viewers. By comparison, photo-texts of the late New Deal era editorialized the circumstances pictured and instructed viewers in their response.

Before Parks moved to Chicago, he frequented the city as a railroad employee. During those stops, he photographed Lake Michigan, seagulls, and skyscrapers near the train station. He also visited the Chicago Art Institute often, which inculcated in him a rather conventional conception of “true” art. Then he began visiting the South Side Community Art Center. Established in 1940 and funded through the New Deal’s Federal Arts Project, the center fostered works of primarily black, but also Jewish, writers and artists. Parks spent more and more time in this space, and when he relocated to the city, he entered an arrangement in which he photographed the center’s exhibits and activities at no charge in exchange for use of its darkroom. His relationship to this generative environment shifted his thinking about art and its purpose. The artists on display at the center had, as Parks recounted, “forsaken the lovely pink ladies of Manet and Renoir, the soft bluish-green landscapes of Monet.” Their works convinced Parks that, in addition to a vehicle for beauty, art could be a medium of protest.

With this mind-set, he trained his camera on Chicago’s South Side, the worst of which he described as “bruises on the face of humanity.” The African American inhabitants of Chicago’s Black Belt became the central focus of his documentary explorations and the basis of his portfolio of what I term race photographs, photographs of black life that signify on the lived experience of race and racism.

In Parks’ hands, the camera became a weapon (as Parks always claimed it was), a means for documenting the adversity inherent to being black in the United States. His presumed insight concerning the subject matter only amplified the critique embedded in his photographs. His race photographs did not perform as statements of national strength; they testified to African Americans’ strength in enduring their place within the nation. In 1941 he was awarded a fellowship with the FSA and moved to the Office of War Information (OWI) two years later. Discussions of Parks’ membership to the FSA/OWI war-era photography team focus on his being African American, the only black photographer charged solely with producing propaganda. The greater significance lies in the seeming conflict between the objectives that he and the government held for his photography. How was he able to marry his proclaimed activist-artistic vision to the wartime mission of the FSA/OWI?

In his role as a federal photographer—which began when Parks was awarded a fellowship with the FSA in 1941 and continued when he moved to the OWI two years later—Parks had to adopt his vision to FSA/OWI narrative and political objectives. Initially, Roy Stryker, head of the FSA Information Division photography unit, allowed, even encouraged, Parks to experiment with both form and subject because, as an intern, his photographs had no assigned purpose, so he was afforded relative “free rein.” But, to train the green intern, Stryker insisted that Parks pore over the FSA files. “It was my daily chore when I first went there,” Parks said, “to look at all the pictures…study them and imprint them on my own conscious.”

Over the next year, Parks accommodated these boundaries to produce depictions of black life, which presented a challenge while he was centered in Washington, DC, which journalist Alden Stevens described as a “blight on democracy.” “Negroes who have lived in many parts of the country,” Stevens explained, “say that nowhere else in America is there such bitter mutual race hatred.” This had certainly been Parks’s experience of the city.

The images he captured of black suffering in the capital of the democratic United States reflect Parks’ continuing impulse to use his camera as a weapon against social injustice—or at least to gather evidence for that fight. While he certainly witnessed and documented hardship, Parks produced photographs that satisfied expectations of him as a federal propagandist.

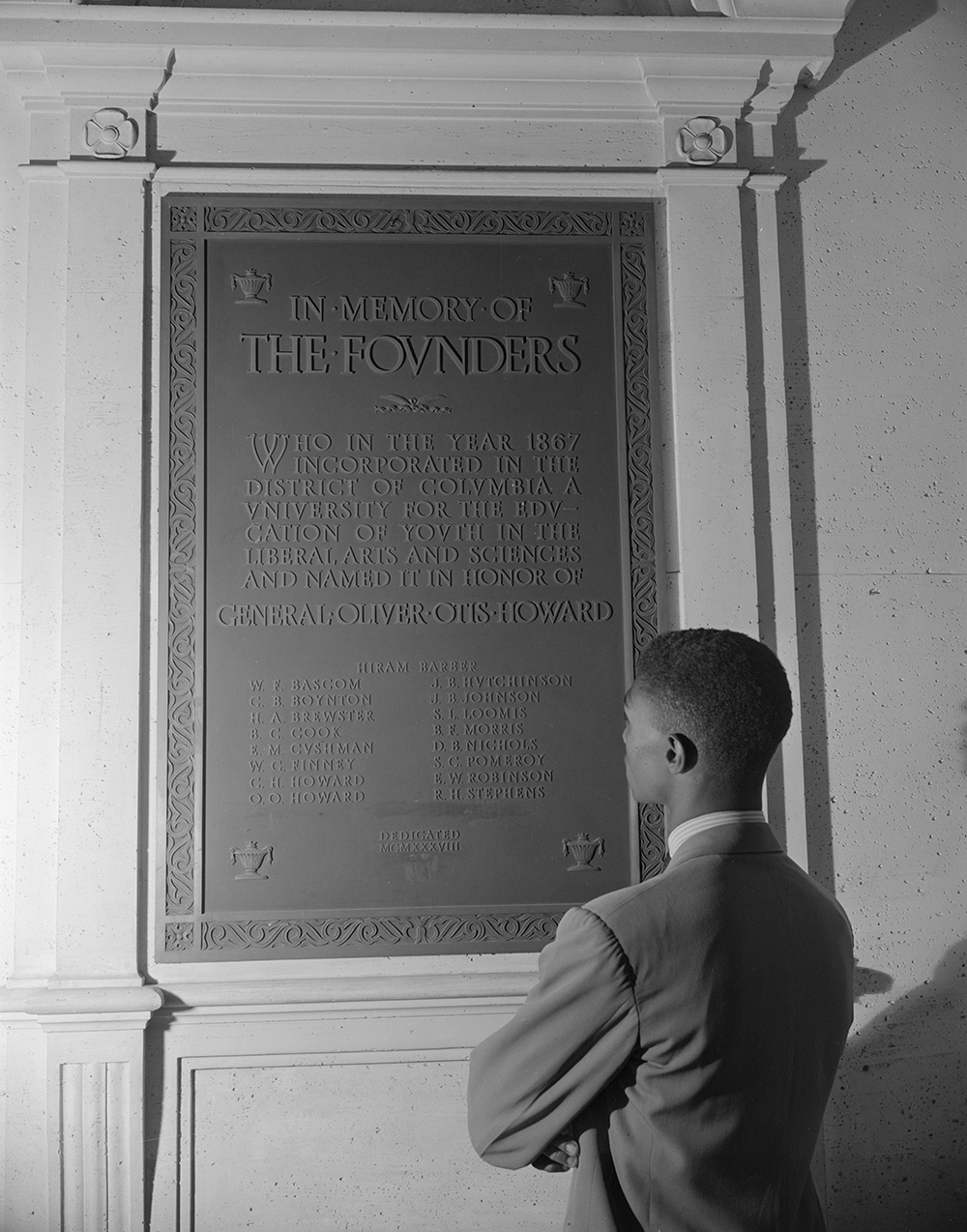

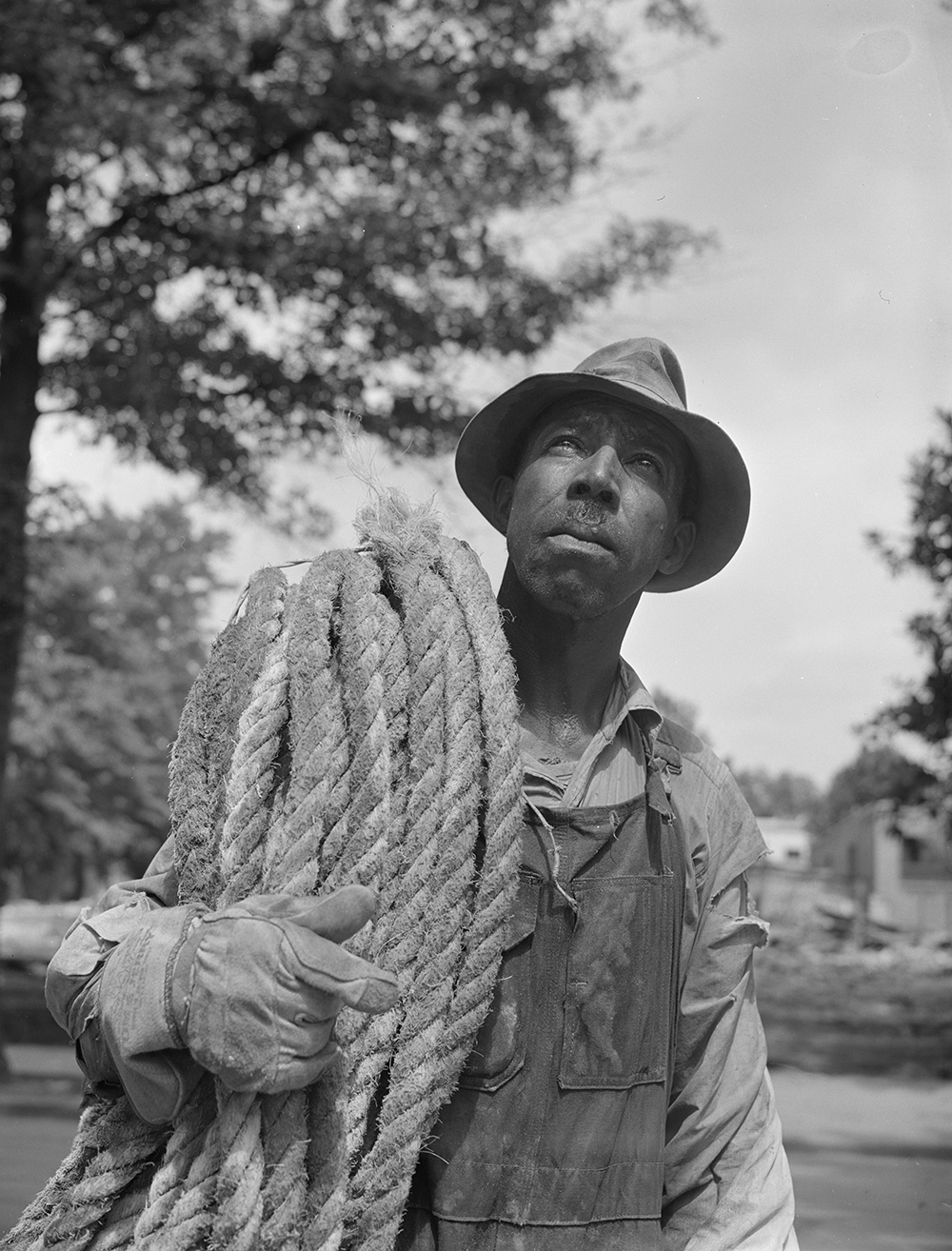

While he toured the city’s black sections, he took multiple photographs of “everyday” African Americans. Many are close-ups of blacks whom Parks clearly persuaded to halt their activities so that he could photograph them. Parks posed his subjects in manners that conferred on them a dignified air and highlighted their communal role: a firefighter shoulders a hose, a delivery driver leans out the window of his truck, a construction worker carries a coil of rope, a mechanic holds a gas nozzle, a security guard stands post, and students carry books. Although constructed as individual portraits, the collective constituted an archive of blacks’ civic belonging within an American community (albeit a black community), as well as their embrace of the responsibilities they had to that community.

Photography historians have observed that the intimacy between Parks and his subjects is evident in the images he created: it distinguished his documentary photographs. His ability to gain the trust of those he photographed allowed him, as scholar Jay Prosser explains in his book Light in the Dark Room, “close-in, low-angle shooting” that created a sense of immediacy for the viewer. In this sense, Parks brought his studio experience to the job of documenting black Americans during World War II.

While certainly political, the image work Parks performed during the war was not oppositional: it resists the common classification of black representational strategies as primarily resistance to oppressive regimes (be it the state or “the gaze”). His photographs disrupt notions of either-or black agency, in which African Americans are portrayed as choosing either purely oppositional or purely accommodationist tactics to advance their politics. Parks pursued his personal, professional, and political objectives with the flexibility of priority and method that African Americans have historically found necessary, or at least effective, when operating in white spaces. His propaganda contributed to hegemonic articulations of the black experience and injected innovative images of African Americans—their experiences, values, and aspirations— into the official portrait of American democracy. He used his wartime assignment as a federal image maker to visually assert, again and again, the national belonging of African Americans through representations of their participation, patriotism, and commonness. This was propaganda useful to black citizenship campaigns. The image campaigns of Parks and other African Americans and the state visibly converge and even reconcile in his photographs. The FSA/OWI photographs of Parks reflect a moment in U.S. history when the state objective of positioning the United States as a global authority, by virtue of its being a democratic society of free people, compelled federal representations of blackness that aligned with the objective of African Americans to be free people in the world’s foremost democratic society.

Excerpted from Represented: The Black Imagemakers Who Reimagined African American Citizenship by Brenna Wynn Greer. Copyright © 2019 by University of Pennsylvania Press. Excerpted with permission of the University of Pennsylvania Press.