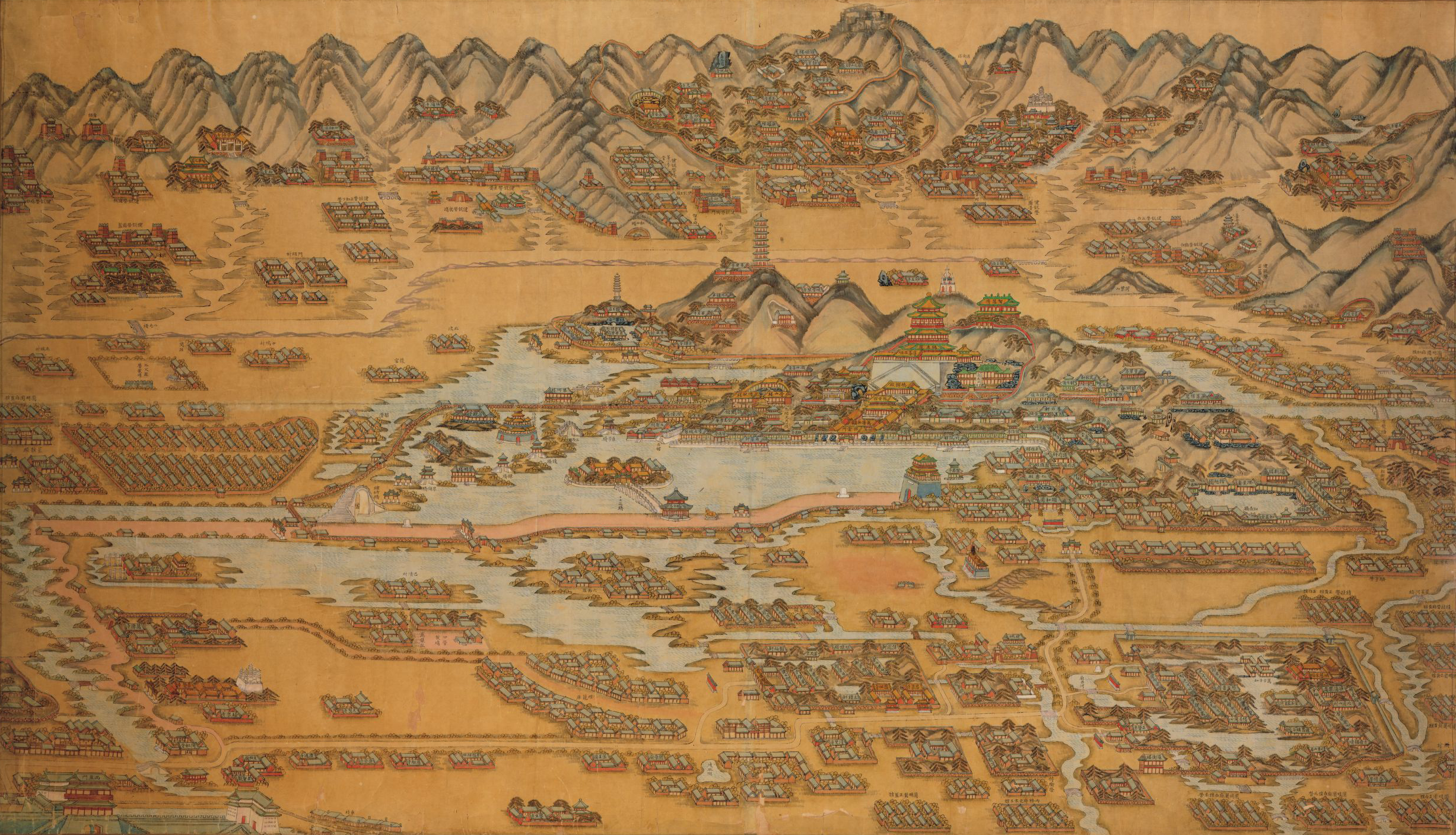

Eight Banners Brigade barracks, temples, villages, bridges, mountains, and the Summer Palace, Beijing, after 1888. Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division.

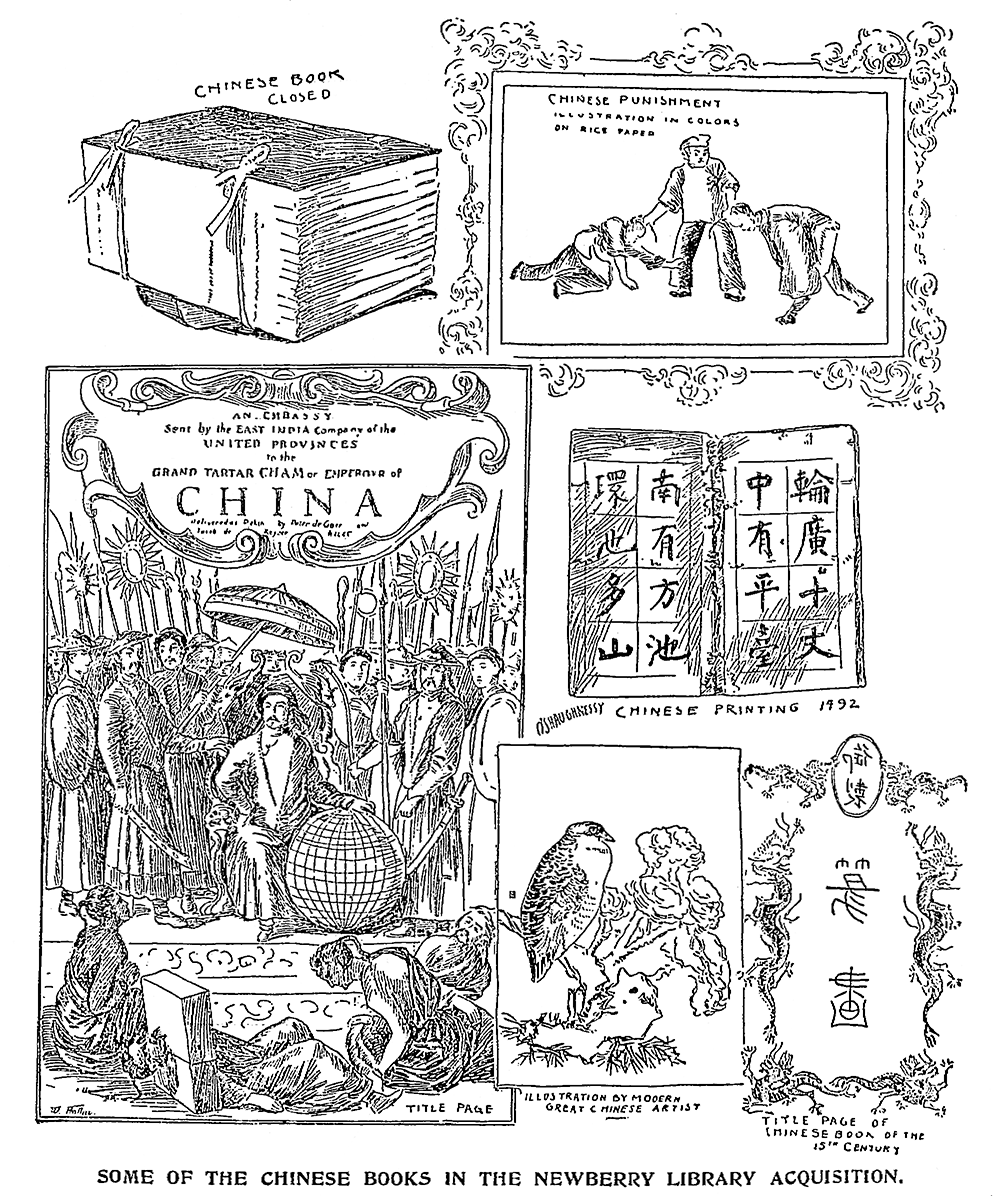

Early in 1896, the Newberry Library in Chicago made its largest purchase to date: 1,290 books from the Tank Kee Collection for about $12,000. The Chicago Sunday Tribune reported that the most treasured “curiosity” was the 239-volume “imperial encyclopedia, used only by the mandarins, and held by them under the government, to which in the end it must be returned, and but one other copy exists outside the empire.” Later that year, G.K. Shimoda, a Japanese architect studying in Chicago, catalogued the collection. Writing to John Vance Cheney, the Newberry’s head librarian, he braved the question on everyone’s minds: how did a Midwestern library come to hold some of the rarest volumes from China?

Encyclopedias have lived with us since antiquity. One of the earliest such comprehensive works was Pliny the Elder’s Natural History; published in the first century, it was an important source for the latest knowledge about geography and natural history during the early Roman Empire. Diderot and his fellow literati published the Encyclopédie, one of the great achievements of the Enlightenment. In China the tradition is just as ancient: the earliest example is Erya from the Warring States period, which separated content into categories such as etymology, geography, botany, and zoology.

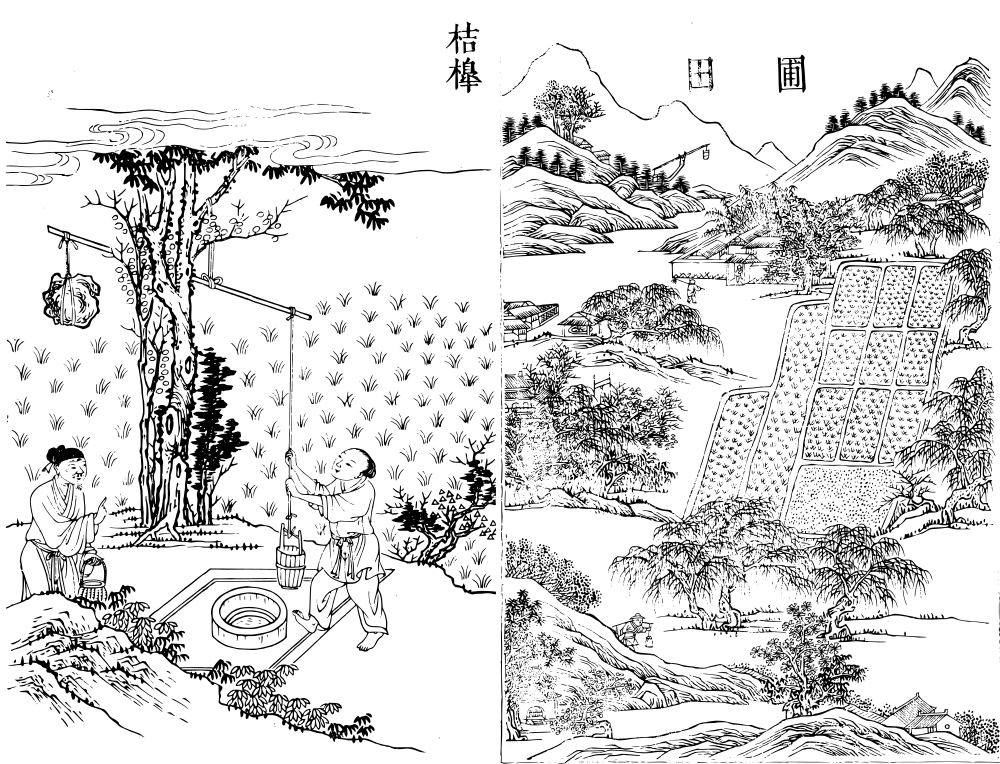

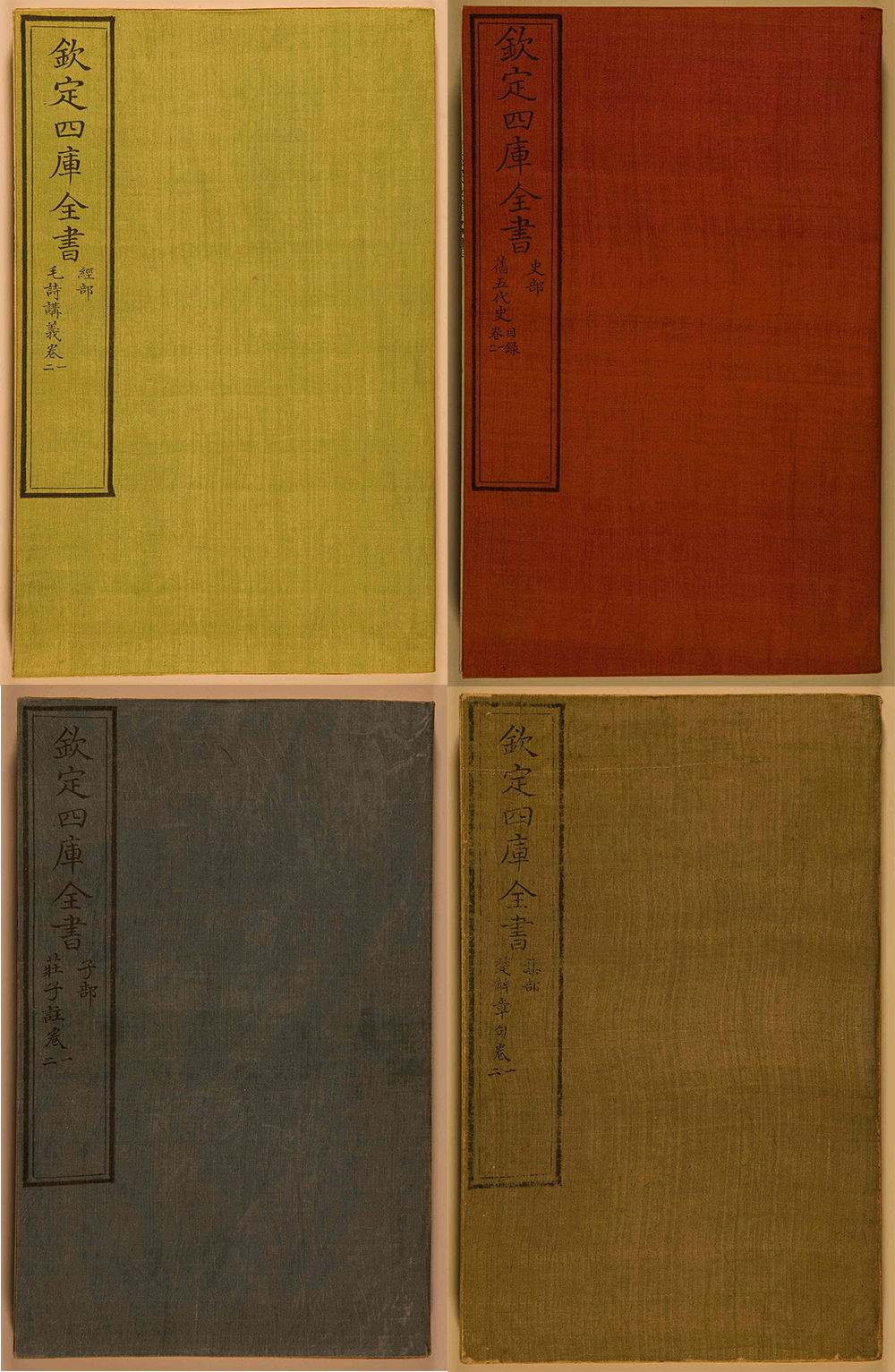

In late imperial China, the two most important encyclopedic works were the Gujin Tushu Jicheng, or the Imperial Encyclopedia, and the Siku Quanshu, or Complete Library of the Four Treasuries. They were more expansive than Western encyclopedias. Not only did they collect general knowledge, they also reprinted ancient literature and commentaries. Both ran to thousands of volumes and were produced with imperial sponsorship. The Imperial Encyclopedia appeared during the Kangxi (1671–1722) and Yongzheng (1723–35) reigns. Chen Menglei, a Fujian official, began the project in 1706. He compiled numerous books of ancient literature, natural history, engineering, and illustrations and structured the encyclopedia on older models. The multivolume set was edited and finalized by Jiang Tingxi between 1723 and 1725. The Siku Quanshu also included classical literature, biographies, and scientific writings. It was completed in 1792, after many years of research and edits. The Siku Quanshu built upon the previous Imperial Encyclopedia as well as other examples, and it served as an important source during the Qing dynasty’s philological revolution in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries (a period similar to the European Renaissance), when Chinese scholars edited and published manuscripts of the Confucian classics and reengaged with classical learning. Because of their unwieldy size, these encyclopedias were primarily deposited in palace libraries and educational facilities. Publishers printed few copies upon first publication, but by the late eighteenth century, scholars studying in the capitals and urban centers could access these works to prepare for the civil service exams.

By the mid-twentieth century, the Newberry had sold most of its Chinese collections, including the encyclopedia. The text’s current location is unknown. The surviving records make it difficult to trace which encyclopedia Shimoda had asked about, but one tantalizing clue hints how the books may have traveled from China to Chicago. The far-right column of the 1896 Newberry Library accession book states that the Imperial Encyclopedia belonged to the George Bailey collection. Who was this George Bailey, and how could he have come to possess such a rare object?

George William Bailey was born in the late 1830s or early 1840s to Ann Scheetz and J.C. Bailey in Philadelphia. We know little about them except that they went to China. George Bailey publicly claimed to have been orphaned and found off the coast of China and raised by the royal family, which is patently false. Bailey’s friend William Payne painted a more reasonable portrait when he wrote Bailey’s obituary for Marshalltown, Iowa’s Evening Times-Republican in 1902, explaining that Bailey’s family moved to China for business when George was a child. The young couple died of cholera, and Bailey was taken in by a wealthy Chinese family and nicknamed “Tank Kee,” a seemingly Chinese name related to the characters for blue-green and remembrance or record. While certain elements of Payne’s account ring true, such as the 1849–52 cholera epidemic in China, the truth remains uncertain. First, there are no known nineteenth-century Chinese or Western sources about Western orphans being raised by Chinese families. Second, “Tank Kee” is more faux than authentic Chinese. Missionary literature provides more information on these networks in China for the end of the nineteenth century to the early twentieth century, but we are left with only hearsay about these early years.

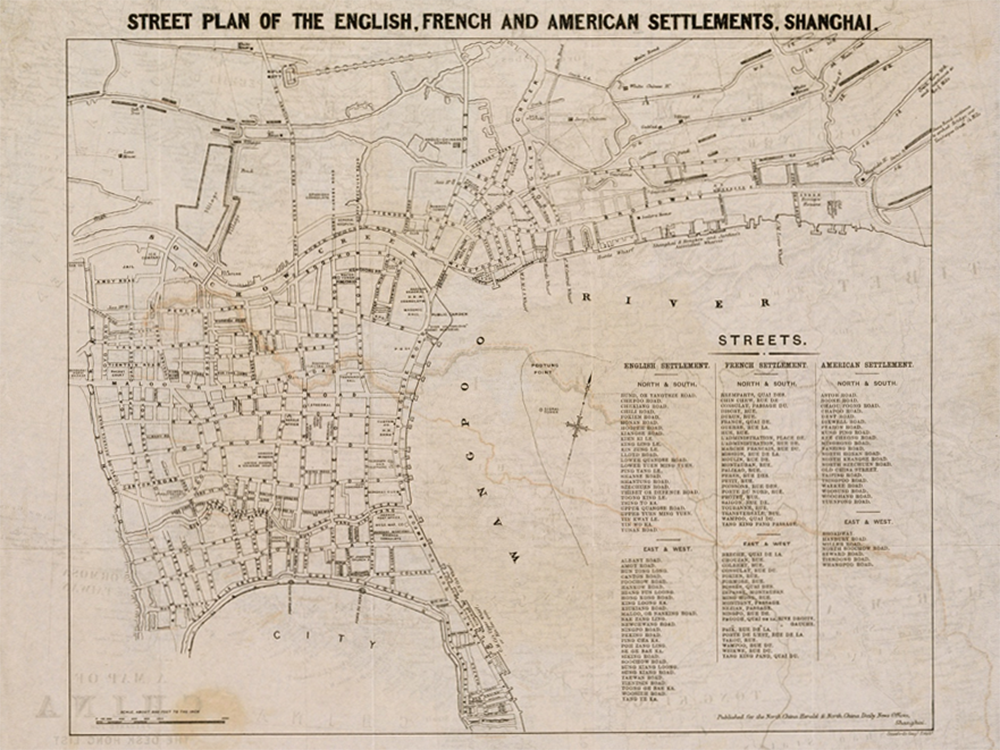

The name George Bailey does appear in military reports, foreign directories, and memoirs from the 1860s and verifies other elements from Payne’s account, however. According to Payne, Bailey joined the Shanghai Foreign Arms Corps, fighting for the Qing against the Taiping rebellion, a millenarian Christian and political reaction to the Manchu dynasty that had crippled the Qing for several years. By 1859 the imperial government had come to welcome foreign support. The Corps, which later became the Ever-Victorious Army, was under the command of the British general Charles Gordon. Gordon’s regiment records show that a G. Bailey had enlisted. Other records describe Major (later Corporal) Bailey’s actions in battles; he managed the artillery and taught Chinese officers how to use them, a decisive element in the Qing victory over the rebels.

Bailey’s connections to Gordon and the Ever-Victorious Army may have involved him in one of the most infamous incidents of the colonial period in China: the looting of the Summer Palace. During the early years of the Taiping rebellion, the Qing also came into conflict with the British in the Second Opium War. The Qing government had limited Western trade to certain ports, such as Canton and Shanghai. The British, French, and other Western powers wanted China to open more ports to facilitate trade, but the Qing refused to comply. The disagreement turned violent, and the British and French started attacking Chinese forces to achieve their goal. After the Qing killed several French and British military officials in Beijing in October 1860, the Europeans decided to attack the capital. As they marched toward the city, the emperor left. With the Summer Palace empty, the soldiers decided to focus their efforts on the imperial residence. Gordon described the carnage: “After pillaging it, we burned the whole palace, destroying it in a Vandal-like manner, most valuable property which would not be replaced for four million pounds.” The soldiers laid waste to the library, including its copy of the Siku Quanshu. Because the palace was the size of a small city, it took days for the entire structure to burn. Meanwhile, soldiers continued to loot.

The historical record is too incomplete to connect George Bailey with these events directly. It is known that by 1879 he had started lecturing about China in a tour throughout the United States that featured many “curiosities”—including dresses, statues, coins, and books. He brought these goods to the South and Midwest, visiting Atlanta, St. Louis, Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul, and elsewhere. One writer stated, “Two of these Chinese dresses have every color of the rainbow worked in the finest kind of needle work. The two at the government value are worth $7,000, and took four years to complete.” As a part of his lectures, Bailey wore these costumes to “illustrate” different roles; sometimes he would use objects, including fans, embroidery, statues, and ivory carvings, as a visual reference. Later, he would design more formal exhibits as curator of the American Archaeological and Asiatic Society, an organization he created in Wichita, Kansas, to share knowledge about China and its history.

Eventually, Bailey sought a permanent home for his Chinese collections. In 1891 he sent a message to Jim Hogg, governor of Texas. He offered to donate everything to the University of Texas if the following terms were met: the university would build a suitable building to preserve the books; the professors would be its trustees; Bailey’s mark would be stamped on all the books; the objects would be repaired; the library would be preserved intact; and, lastly, the building would be named the Tank Kee Library. The Dallas Morning News estimated that the 33,000 volumes were valued around $120,000 to $150,000, a massive sum for the time, and the university wanted the collection. A month later, none of the books had been delivered, however. A reporter asked Bailey why he was delaying, and Bailey said that the University of Texas would not build a fireproof building and wanted only to add his books to the general library, a proposition he would not accept. Bailey said, “The library is not a college one, and it is intended for those who have passed beyond college life.” As soon as the university agreed to his building demands, Bailey added, “I stand ready to ship the library at a rate of 5,000 volumes a month.” But the two never came to an agreement about the building, and the deal collapsed. Rumors circulated that he needed money and had changed his mind about giving away his collection.

Bailey tried to find new managers for it two years later. First, he went to the Masonic Library in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. At the time, he was living in Nevada, Iowa, where he housed the materials he wasn’t using on his lecture tours. In 1893 he approached Newton Parvin, the head of the Masonic Library and leader of the Iowa Freemasons. He offered to donate his collection under the same conditions he had proposed to the University of Texas, emphasizing a fireproof building, but he also wanted help with transportation costs. Parvin visited him in August 1893 and wrote up a contract. By the end of September, Bailey came to Cedar Rapids and signed it. Bailey immediately started moving books and materials to the Masonic Library.

Yet just a few months later, Bailey claimed he had been on opiates at the time of the transaction and was not in his right mind—he wanted the library returned. According to one story, he went to the Masonic Library, demanded the return of the collection, and fired shots throughout the building, nearly hitting Parvin. After the shooting, he disappeared, but he eventually contacted the police and said he wanted to turn himself in. Deputy U.S. Marshal Mike Healey told him to come to the Cedar Rapids police station, and Bailey replied with what a newspaper account claimed to be a ten-thousand-word telegram telling the story of his life and filled with “slanderous” comments about Parvin. He wrote that Parvin had wanted him killed and that the Masonic Library was trying to steal his collection. Bailey was arrested not for reckless conduct but for abusing the mail and telegraph system by slandering Parvin. Ultimately the Masonic Library agreed to return the material; while the Freemasons claimed Bailey was of sound mind when he made the contract, they also said he had an opiate habit, which may have been a factor. Even his friends admitted he had an addiction, and Bailey was noticeably drunk on more than one occasion as well, including when lecturing to temperance societies. The Masonic Library agreed to return his books and materials if he returned the $755 already paid.

After the incident with the Iowa Freemasons, Bailey contacted the Newberry Library. Founded in 1887, the Newberry was actively seeking to expand its holdings. Instead of trying to donate the entire collection and negotiating payments for transportation and other costs, Bailey offered to sell many of the English books on China, the Chinese encyclopedia, seventeenth-century Jesuit texts, Chinese paintings, and military maps. He told the Newberry that he had acquired most of his books during his thirty years living in China. While his entire collection was valued at more than $100,000, he sold these volumes for $12,000 to the Newberry, more than recovering the costs incurred from his Masonic misadventure.

While Bailey had always presented himself as an expert on China, after leaving Iowa in 1894 for Kansas and then Minnesota he also started calling himself an archaeologist, even if it wasn’t clear why he was qualified to be known as Dr. Bailey. He continued to travel throughout the Midwest and Southeast and lecture about China until his death in 1902. At one point, he even ran afoul of the conservative Texan columnist William Cowper Brann, also known as Brann the Iconoclast, whose inveterate roasting included comparing an extravagant costume ball to “the rank eructation of some crapulous Sodom, a malodor from the cloacae of ancient capitals, a breath blown from the festering lips of half-forgotten harlots, a stench from the sepulcher of centuries devoid of shame.” Under the byline Tank Kee, Bailey had written a number of opinion pieces criticizing America’s growing anti-Chinese sentiment, which brought him into Brann’s sights. During Bailey’s tour of the Southeast, he wrote what came to be known as the “Mississippi Letters,” which shared his thoughts on race and culture in the Jim Crow South. They were not well received. Brann called them “the most brutally slanderous of the South and the Southern people than anything yet put in print…One thing is cock-sure—Tank Kee had best keep out of Texas.”

By the late 1890s, visitors had stopped coming to see his Chinese curios. He sold some of the collection and also kept donating objects to scholarly institutions, including several Buddhist statues he sent to the Smithsonian. The obituary his friend William Payne wrote covered the crazy twists and turns in the life of Bailey, from his travels in China to his lectures in America. With such an adventurous life, it’s no wonder that the strange story of how an imperial encyclopedia came to the Newberry Library didn’t merit any mention.