View on the Columbia, Cascades, 1867. Photograph by Carleton E. Watkins. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Warner Communications Inc. Purchase Fund and Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1979.

American field biologists have a long history. On April 30, 1803, the United States purchased the vast Louisiana Territory from France. As entomologist Howard Evans wrote: “The Louisiana Purchase…approximately doubled the size of the United States, adding 800,000 square miles of ignorance—land that had never been well explored or adequately mapped.” Two months later, on June 20, President Thomas Jefferson gave the following instructions to Captains Meriwether Lewis and William Clark:

The object of your mission is to explore the Missouri river, & such principal stream of it, as, by its course & communication with the waters of the Pacific Ocean, may offer the most direct & practicable water communication across this continent, for the purposes of commerce.

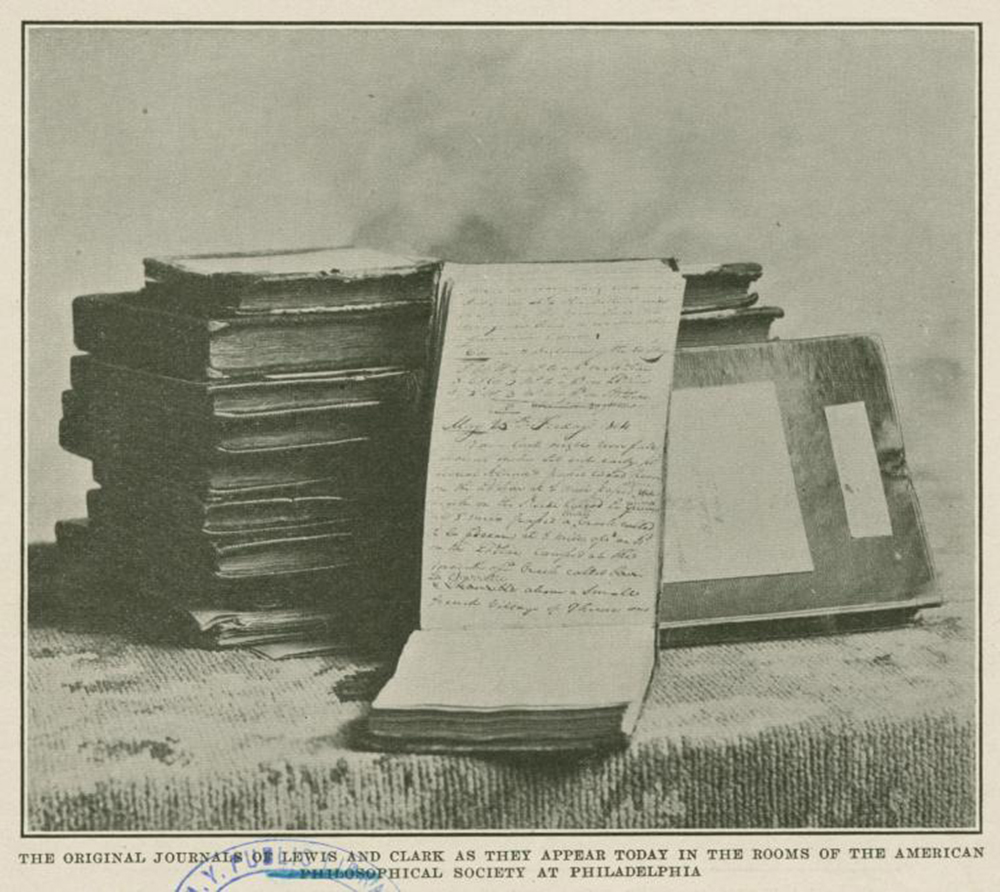

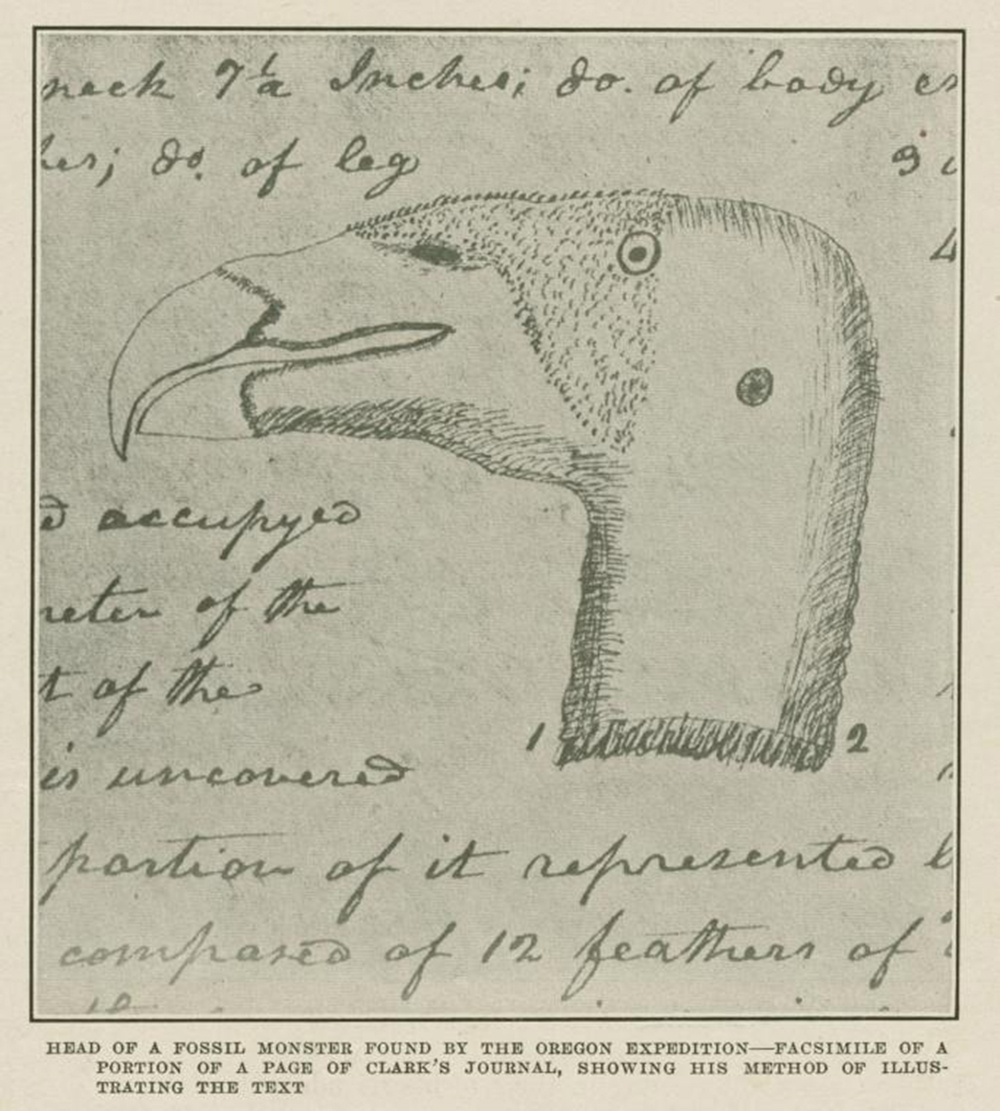

Five biological/sociological features of Lewis and Clark’s journals stand out. The first is the vegetational structure of the fire-dominated landscape of the Great Plains. The second is the collection of plants and animals at identified geographic locations—many of which no longer occur at these sites, or indeed across much of their historic range. The third is the large number of animals, especially the big mammals—bison, deer, and elk; from their accounts, it is easy to see why the Great Plains has been referred to as the North American Serengeti. The fourth is the attention to detail in their descriptions of animal specimens, especially new species. And the fifth is their observations of, and interactions with, an already depleted Native American population. Although Lewis and Clark’s biological specimens were never used to their potential, their tally of new species ran to 178 plants and 122 animals. Of the animals collected, only one specimen, a Lewis’ woodpecker (Melanerpes lewis), survives intact, at Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology, where it was transferred in 1914.

The Philadelphia Academy of Natural Sciences, founded in 1812, was the first great American scientific institution. Early on, it was the chief American repository for new biological specimens being shipped east; it is where Lewis and Clark sent their plants and animals. Slowly, Lewis and Clark’s species descriptions appeared in print. As early as 1808, their birds were being described and illustrated by ornithologist Alexander Wilson.

In 1814 the botanist Frederick Pursh described seventy-seven plant species in his Flora Americae Septentrionalis, and naturalist George Ord described ten animal species, including grizzly bears and pronghorn antelopes. Also in 1814 a condensed and filtered version of Lewis and Clark’s journals was published. A planned second volume, covering the voyage of discovery’s natural history and geological accomplishments, was never published because the editor, Benjamin Smith Barton—Lewis’ mentor—was too ill.

As Jefferson anticipated, commercial enterprises followed the voyage of discovery. Two years after Lewis and Clark’s return, the German-born John Jacob Astor founded the Western Division of the American Fur Company to break American dependence on the Hudson’s Bay Company’s monopoly on beaver pelts. In July 1806, before Lewis and Clark’s return, General James Wilkinson, governor of the Louisiana Territory, ordered Zebulon Pike to explore the source of the Red River, the legal boundary between American and Spanish lands. Pike’s outfit discovered the mountain named for its leader and pioneered the Santa Fe Trail. Teddy Roosevelt admired Pike, but “nothing that Pike ever tried to do was easy, and most of his luck was bad.” By Pike’s own admission, he was an untrained naturalist and lacked the “time and placidity of mind” required to study the plants and animals he encountered. During his expedition, Pike and some of his men were captured by the Spanish and held for several months in Chihuahua before being released. Roosevelt’s admiration notwithstanding, Pike’s report, published in 1810, was considered “poorly organized, unreliable…scientifically and geographically incorrect, and in many places dishonest.”

These early government-sponsored expeditions have been described by historians as explorations, but in fact they were driven by commerce. Working out of St. Louis, Manuel Lisa and his partner Andrew Henry established the Missouri Fur Company in 1809, which sent expeditions up the Missouri River to open this region to trade. The Missouri Fur Company conducted their operations out of Fort Lisa, near present-day Omaha, and more distantly out of Fort Raymond on the Yellowstone River, in eastern Montana. Lisa’s trappers combed the Rockies. For example, John Colter (a member of the voyage of discovery, once reprimanded for his behavior) discovered the geysers of Yellowstone during an 1807–8 trip. Lisa’s men also found a route down the Rockies to Santa Fe, the Spanish center of commerce, during the 1811 exploration led by Jean-Baptiste Champlain. The Missouri Fur Company’s explorations eventually accumulated so much information useful to William Clark’s mapping project of the West that in 1814 the U.S. government rewarded Lisa by appointing him as agent for Indian affairs in the upper Missouri region.

Lisa’s Missouri Fur Company both assisted and enabled exploration, but the major players in the trade in beaver pelts were the American Fur Company, founded in 1808 by Astor, and the Rocky Mountain Fur Company, formed in 1822. Early in its history, the American Fur Company used the Missouri and Columbia Rivers and their tributaries to transport supplies and equipment in and furs out—they were, in essence, voyageurs (boatmen). In 1811 the American Fur Company sent a party led by Wilson Price Hunt up the Missouri. They eventually made their way, following the trail of Lewis and Clark, to the Pacific, where they founded the town of Astoria. Traveling with Hunt as far as the Arikara villages in present-day North Dakota were the British botanists Thomas Nuttall and John Bradbury. In 1817 Bradbury wrote an account of this trip in Travels in the Interior of America in the Years 1809, 1810, and 1811. In addition to describing plants collected by Lewis and Clark, Pursh’s Flora Americae Septentrionalis (1814) described, without permission, plants collected by Nuttall and Bradbury. The American Fur Company improved traditional methods of river transportation by introducing steamboats to the upper Missouri. Astor’s company operated fixed trading posts and relied on Indian trappers; it traded in all furs, as well as feathers, meat, and lard. Largely because of its tendency to trap out areas and move on, by 1833 beaver had become scarce, and bison robes became their primary commodity.

In contrast, the Rocky Mountain Fur Company worked on land, away from rivers, using pack trains up the valley of the Platte River and through the South Pass. (In 1812 American Fur Company trapper Robert Stuart, traveling back east from Astoria, found a way through the Rockies at South Pass, Wyoming, in what was to become the route of the Rocky Mountain Fur Company and, a few decades later, the “Oregon Trail,” and then a few decades after that the route of the Union Pacific Railroad.) The Rocky Mountain Fur Company maintained no fixed posts, traveled in small parties, caught their own beaver, and traded with Native Americans as chance opportunities arose or at their annual rendezvous, which occurred during the summer at a predetermined time and place. Their employees became the prototypical and highly celebrated mountain men, including Jim Bridger, Kit Carson, and Tom Fitzpatrick. They would opportunistically trap marten, otter, mink, and fox, but their interest in bison did not extend much beyond personal use. Gradually, the distinctions between the American and Rocky Mountain Fur companies dissolved and by 1833 had disappeared. By then, through their complimentary approaches, they had opened the West. The federal government sponsored other explorations concurrent with, but less well known than, Lewis and Clark’s. In 1804 William Dunbar led a three-month expedition with George Hunter as naturalist, up the Ouachita River, a tributary of the lower Red River. There, they found the Hot Springs area of central Arkansas. Dunbar was an inventor, and he worked out a novel way of calculating longitudes based on lunar altitudes; he also designed flat-bottomed boats for exploring shallow prairie rivers such as the Missouri. In April 1806 Thomas Freeman led a second Red River expedition. Peter Custis was the naturalist, and together they traveled upriver 615 miles before being forced by Native Americans to turn back. These two Red River surveys were the first to deploy civilian scientists (Hunter and Custis). Despite not achieving their goal of clarifying the boundary between the Louisiana Purchase and Spanish-held territories, they did assemble accurate, detailed maps, as well as information on the geography, biology, and Native Americans of the region.

Wallace Stegner noted what ship-bound British naturalists had already experienced, that hazardous and unsecure conditions associated with early expeditions (e.g., traveling by boat over water—or, worse, on fast-flowing rivers—or by horseback and wagon; having only tenuous shelter in the evening and during storms; and coping with subfreezing conditions) caused biological specimens to wet and rot or be lost. As John Frémont related in a letter to the botanist John Torrey:

Though in the course of our journey the Bales of plants had been twice wet, yet they were in very beautiful order when we encamped on the upper waters of the Kansas on the 13th of July, in the course of which night it began to rain violently & towards morning the river which was over one hundred yards wide suddenly broke over its banks, becoming in less than 5 minutes more than half a mile in breadth. Everything we had was soaked. We were obliged to move camp to the Bluffs in a heavy rain which continued for several days and one fine collection was entirely ruined…I brought them along and such as they are I send them to you. They are broken up & mouldy and decayed, and today I tried to change some of them, but found it better to let them alone.

This sort of mischance happened to every collector. Prince Maximilian of Wied-Neuwied lost most of his plant and animal specimens when the steamboat Assiniboine caught fire and burned on the Missouri River; Pike’s field notes were confiscated by Spaniards; a portion of Thomas Say’s and Edwin James’ field notes were carried off by deserters; Joseph Nicollet’s botanist, Charles A. Geyer, lost his plant collection in shipment from Fort Snelling to St. Louis; and Charles Parry’s specimens from the Mexican Boundary Survey were destroyed in a warehouse fire in Panama. Some threats recurred: Nuttall had trouble keeping his lizard and snake specimens hydrated because Native Americans kept drinking the alcohol from his collecting jars.

Aware of these dangers, Jefferson recommended to Lewis and Clark that they write field notes on birch bark, “it being little liable to injury from wet and other accidents.”

Reprinted with permission from This Land Is Your Land: The Story of Field Biology in America by Michael J. Lannoo, published by The University of Chicago Press. © 2018 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved.