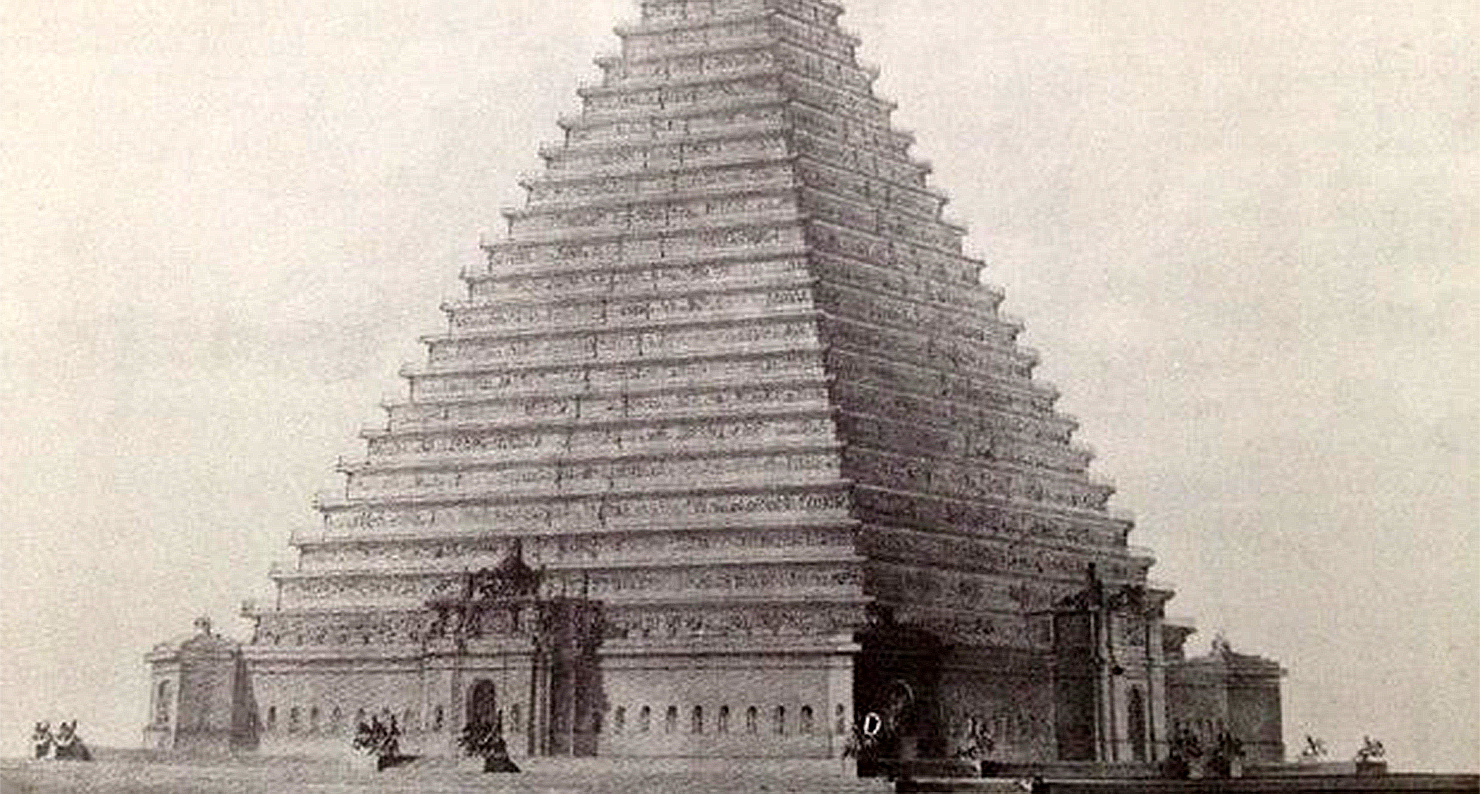

Design for The Metropolitan Sepulchre, by Thomas Wilson, 1829.

Designers Yalin Fu and Ihsuan Lin recently unveiled a plan for a new skyscraper in Mumbai, the Moshka Tower, but what separates this skyscraper from others is its occupants: the Moshka Tower is not for the living, but the dead. Designed as a massive necropolis, the Tower is envisioned as the final resting place for Mumbai’s dead. As the designers explained:

Traditional cemeteries take up space that will never be gained back in the future. The Moksha Tower project takes traditional burial methods from four major religions in Mumbai and translates them into an urban context. The tower frees up a significant amount of ground space for the living and provides within it a place of rest for the departed. The tower seeks to meet the needs of the entire burial process for several cultures within the city and create a temporary place of repose in the sky. It also acts as a symbolic link between heaven and earth. For Muslims, it provides areas for funerals and space for garden burial; for Christians, areas for funerals and burial; for Hindus, facilities for cremation and a river to deposit a portion; for Parsis, a tower of silence is located on the roof of the tower.

Mumbai would not be the first city to house a “vertical cemetery.” Since 1983 the Memorial Necrópole Ecumênica in Santos, Brazil, has provided an elevated home to the dead—a thirteen-story building perched high on a hill that’s in Guinness Book of World Records as the highest cemetery in the world. In Bogotá, Colombia, the recently proposed Panteón Memorial Towers would likewise elevate the remains of the departed into the heights through thirteen minimalist towers. And at the 2006 Venice Bienniale, South Korean architect Chanjoong Kim recently proposed “The Last House,” a skyscraper cemetery where a cell phone call could light up the specific receptacle of your loved one’s remains, so you could view them from a distance.

These plans come directly out of the changing nature of the urban landscape and the problem of overcrowding that plagues many of these super-metropolises. As Fu and Lin put it, “In Mumbai, there is little recreation space for the living, never mind the dead.” But if this seems like strange and uncharted new territory, the idea is not new at all.

The pyramids at Giza represent the oldest skyscraper necropolises, of course. For over 3,800 years, Cheops’ pyramid was the tallest structure in the world, and long cemented the idea that tall buildings belonged to the dead as much as to the living. But Egyptian pyramids were meant to hold only a few bodies of kings, not the masses from overcrowded cities. This was the situation facing metropolises like Paris and London in the early nineteenth century, when overcrowding and poor sanitation problems overwhelmed parish cemeteries. Attempting to respond to the crisis, city governments turned to architects and civil planners for burial solutions.

In 1820 a little-known architect named Thomas Wilson proposed a plan for “a metropolitan cemetery on a scale commensurate with the necessities of the largest city in the world, embracing prospectively the demands of centuries, sufficiently capacious to receive five million of the dead, where they may repose in perfect security, without interfering with the comfort, the health, the business, the property, or the pursuits of the living.” What he proposed, in short, was a massive pyramid, its base covering eighteen acres and its height well above that of St. Peter’s Cathedral—a metropolitan sepulcher, a skyscraper for the dead.

Wilson envisioned massive flights of stairs on each side of the pyramid, leading to an obelisk on top that would include an observatory. In the gardens around the pyramid, a sculpture garden would counterpoint the “bold, monotonous, and sombre background of the pyramid;” not just a house for the dead, it would be a monument for all of London.

“This grand mausoleum,” Wilson claimed, “will go far towards completing the glory of London. It will rise in majesty over its splendid fanes and lofty towers—teaching the living to die, and the dying to live for ever.” Moreover, it would pay for itself. At £5 per burial (around $500 today) the project would return a tidy profit for its investors.

Wilson’s idea was rejected in favor of the garden cemetery plan recently pioneered in Paris’s Père Lachaise. Specifically, the cemetery was designed as an antidote to city life; it was an idyllic natural repose where the living could escape the bustle of the city by communing in verdant fields with their loved ones. Wilson’s pyramid, on the other hand, was to be an extension of it—just as urbanites dwelled in spectacular architecture and ever-taller buildings, so too might their dearly departed.

Now, almost two hundred years later, necessity is once again enlarging how we view the dead and what we will accept as their final resting place. In these new spires of mourning, we hearken back to Cheops’s Pyramid and Wilson’s Metropolitan Sepulcher, recalling the past even as we prepare for the future.