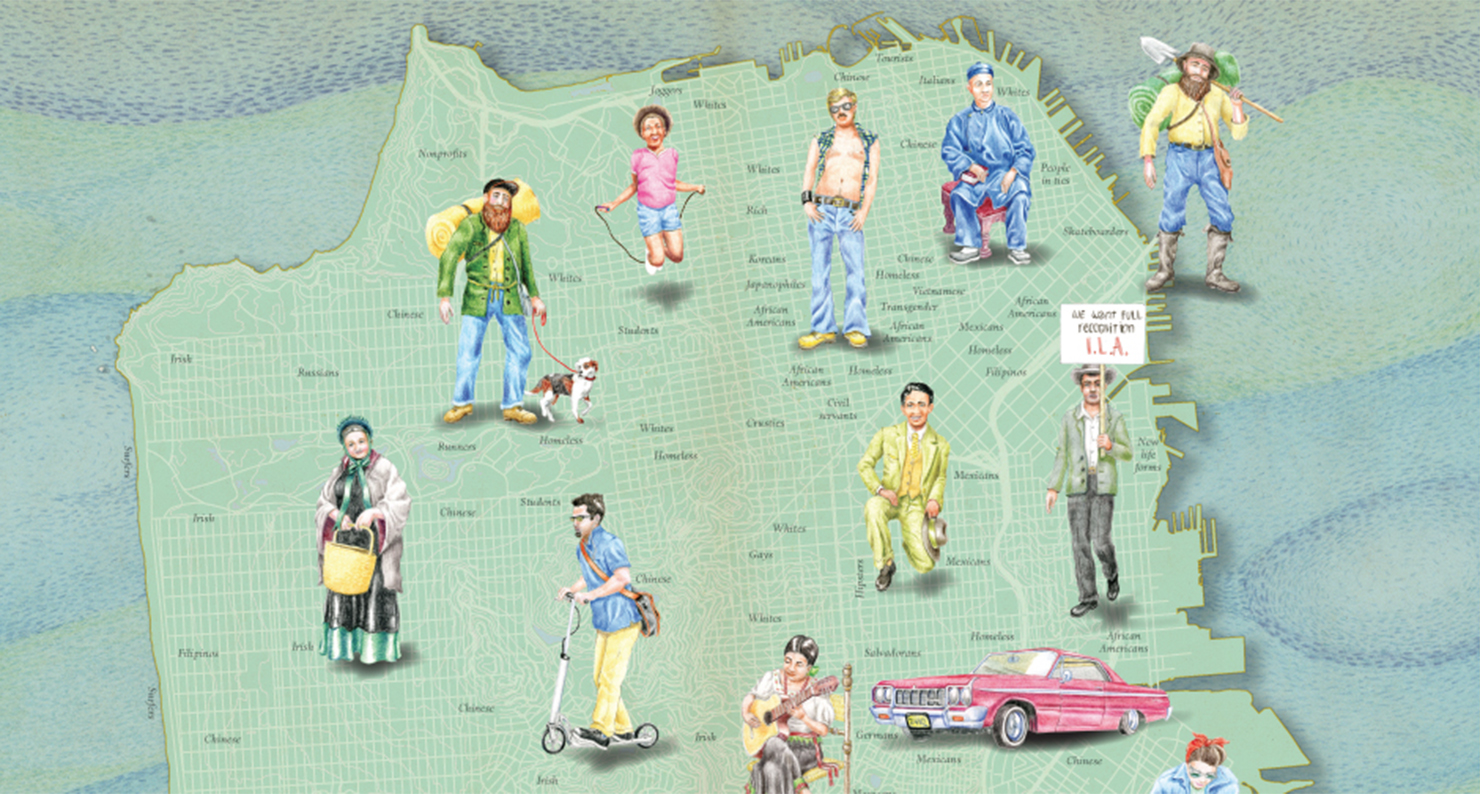

Tribes Map from Infinite City: A San Francisco Atlas, by Rebecca Solnit, 2010.

“A city is a particular kind of place, perhaps best described as many worlds in one place.” So writes Rebecca Solnit in the preface to her splendid atlas of the city for which she’s come to serve as literary partisan-in-chief, and about a work of geography fully alive to the double-meaning embedded in the term (from the Latin geo-graph: “to write the world”). Like all places, San Francisco has a literal geography—its hills and bay; its site at the tip of a peninsula on North America’s Pacific rim. But it has an imaginative geography as well: the set of stories that its boosters and bewailers have told about the worlds that make up their place—a city that’s gained its repute, from the Gold Rush to Flower Power and Black Power to Facebook and gay marriage, as “the un-American place where America invents itself.”

Growing from a project commissioned by San Francisco’s Museum of Modern Art, Infinite City is based in the principle that “every place is if not infinite then practically inexhaustible”—that every one of San Francisco’s 800,000 residents, from Oaxacan day-laborers to latte-swilling geeks, lives in a different city. And that they could, accordingly, map their city in infinite different ways. Most city-dwellers, whether they get around by bus or car, have some sense of how their city looks in two dimensions. But all maps, whether commissioned by the MTA or AAA (or the maps below for SFMoMA), are arbitrary. Like storytellers, cartographers make meaning as much by data left out as by what they leave in. All maps are arbitrary—or, better put: all maps express the aims of their maker. This, in any case, is the base conceit of an atlas that includes, under Solnit’s guiding vision, the varied perspectives of a merry band of contributors of which I was lucky to be one.

Some of Infinite City’s twenty-two maps tell under-told stories in cartographic form—“Right Wing of Dove,” for example, undercuts the image of the Bay Area as liberal monolith by mapping bastions of Bush-style militarism from Bechtel’s corporate headquarters to the Berkeley office of torture-legalizer John Yoo. Most maps and their companion-essays tend toward the obliquely poetic. “Death and Beauty” maps the sites of every one of 2008’s ninety-nine murders in San Francisco proper, alongside most of the magisterial Monterrey cypresses growing in its bounds. “Monarchs and Queens,” again juxtaposing ecologies natural and human-made, maps historic butterfly habitats with queer public spaces that have long afforded exultant sheddings of their patrons closet-cocoons (i.e. gay bars). “Poison/Palate,” complicating the Bay’s illusory image as preternatural font of the Fresh & Local, maps Superfund sites and nuclear dumps alongside foodie shrines like Marin’s Cowgirl Creamery and Berkeley’s Chez Panisse. “Shipyards and Sounds,” with its mapping of World War II-era shipyards and musical landmarks, implies a story about African-Americans lured to San Francisco from Dixie to build ships during the war, only to end up, once the shipyards closed, marooned jobless on foreign shores—or, as Otis Redding put it, “Sittin’ on the Dock of the Bay.”

No small part of the pathos intrinsic to the Golden State epic, and the story of its exemplary city, lies in the truth that the California Dream as often proves illusory as real. Like all cities, San Francisco’s vibrant drama derives from the proximity in which it emplaces dreams realized and dreams deferred; thriving start-ups and shuttered shipyards; grim ghettoes are shining towers. Such are the juxtapositions highlighted in Infinite City, an atlas whose maps of a few of its subject-city’s many worlds remind us why cities perhaps matter most of all: as places that help us believe and see that anything is possible.