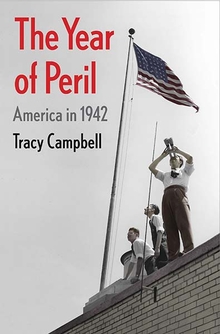

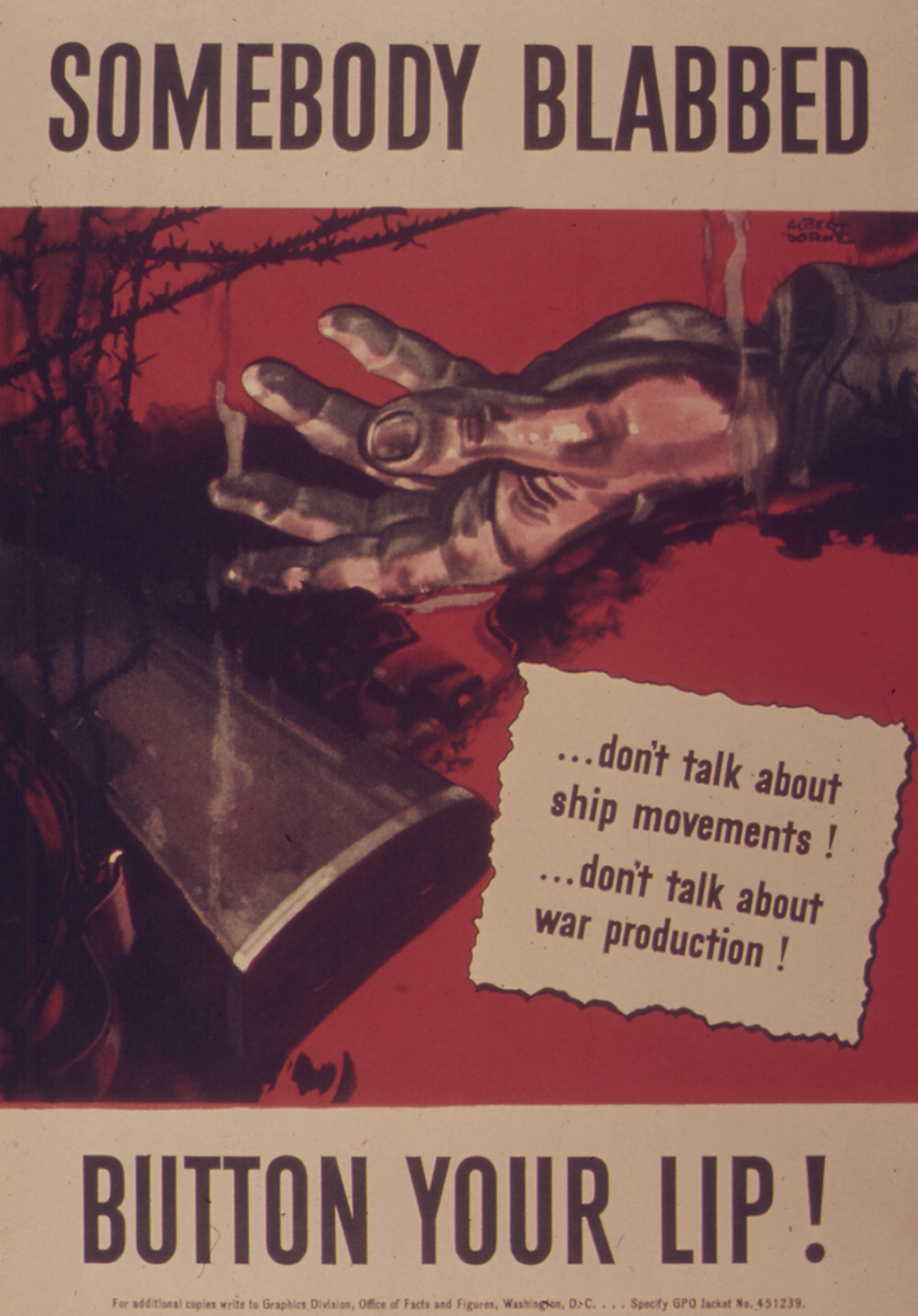

WPA poster by Vera Bock, c. 1941. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

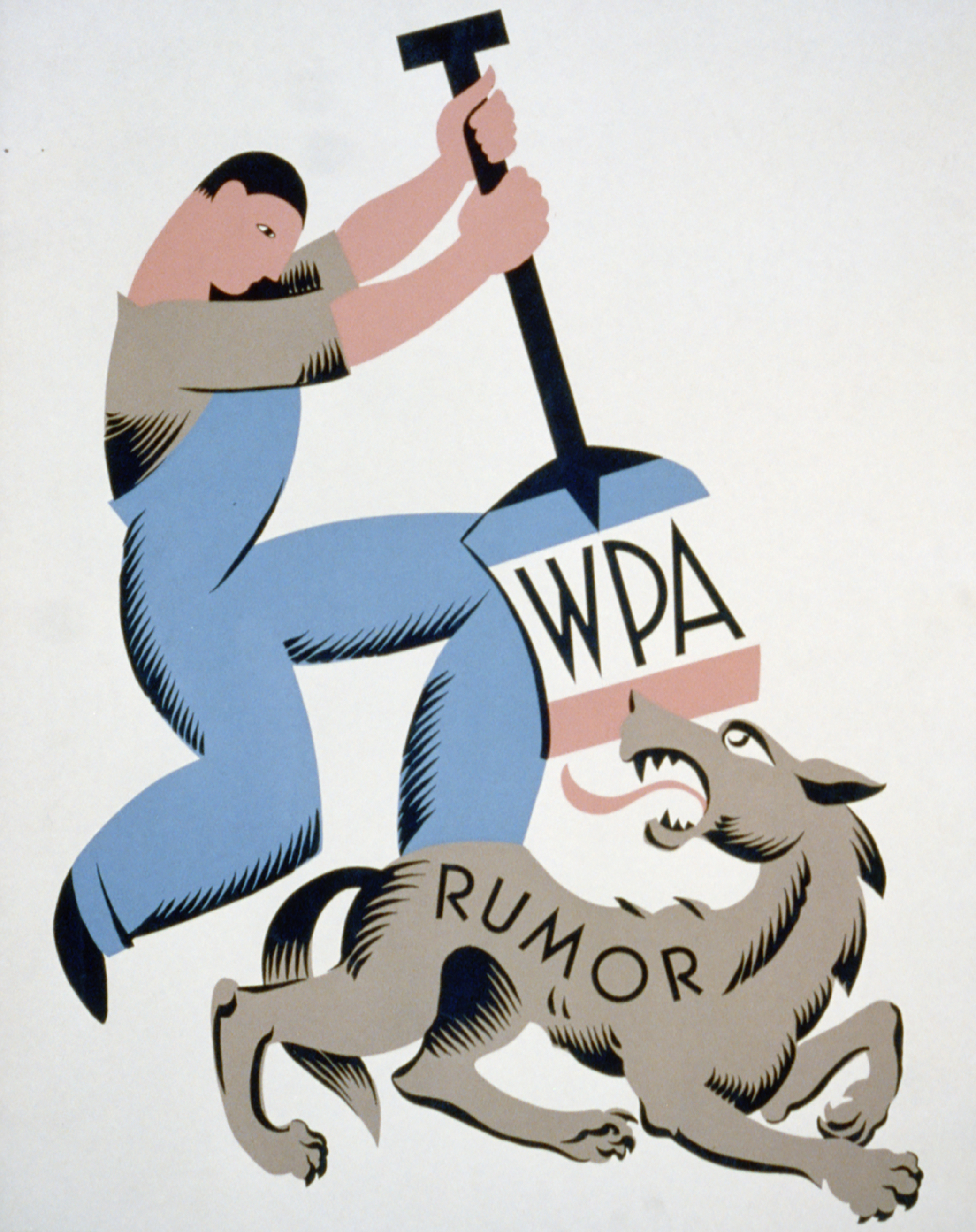

“In a total war,” argued the War Department’s Bureau of Public Relations, “words are weapons.” Phony stories that circulated throughout communities and regions were especially dangerous. “Rumor is one of the weapons employed by the enemy against the effectiveness of the Army.” Office of Facts and Figures head Archibald MacLeish warned that “Hitler thinks Americans are suckers,” and an educational periodical suggested that many rumors “are Nazi-inspired.”

While the nation’s enemies might have wished to plant rumors among Americans to damage morale, they could not have invented anything better than the rumors coming from within the country itself. Modern readers concerned about the spread of misinformation may be interested to know that this is not a recent development.

The impact of rumormongering on national morale was on President Roosevelt’s mind just days after Pearl Harbor. In his first fireside chat after the attack, he urged Americans “to reject all rumors,” noting that “these ugly little hints of complete disaster fly thick and fast in wartime.” Many of the rumors flying through the nation’s capital concerned the true extent of the damage done at Pearl Harbor and what city would be targeted next.

To stay atop the most widespread rumors and perhaps find a way to counter them, in 1942 the Roosevelt administration began systematically monitoring Americans. The Office of War Information, created by executive order on June 13, 1942, initiated the War Rumor Project, which relied on barbers, bartenders, doctors, hairdressers, police officers, and drugstore owners to eavesdrop on their neighbors and customers and report what they heard to their local OWI office. The use of such “rumor reporters” was not new; Roman emperors had appointed delatores to mingle with the general population and report back any criticisms of the emperor. The OWI’s army of “reporters,” who surreptitiously listened to offhand remarks, conversations, and idle speculation, left us a remarkable window into the darker corners of wartime America’s psyche.

The OWI set out three distinct criteria for “detecting a rumor.” The statement had to be offered as a fact, not opinion; it had to originate with a private source of information not generally available to the general public; and it had to contain a specific, rather than a general, assertion. The OWI collected these rumors in order to respond in the best way. “Ineffective replies,” the agency stated, could ultimately “increase anxieties to the point where rumors are generated on all sides.” It was “the duty of every loyal American to enlist in the campaign to prevent the development of virulent rumors.” While not every rumor could or should be answered, the OWI hoped to combat “the more prevalent” ones “by striking at their root—ignorance.” The agency felt that by quickly responding to what people were telling each other, it could make people better informed and thus better able to discount the misinformation that was spreading around them. Although the OWI would focus on the “constant preparation of informational materials,” it hoped to prevent “the community from feeling that a Gestapo is being organized.”

The OWI selected its army of reporters carefully. Since “rumor travels along social networks,” a “good rumor reporter is one who has many social contacts. He should, however, be the sort of person who, either through occupation or temperament, is on the periphery rather than in the center of the group.” Such people came from all walks of life. In Florida, one rumor reporter was a salesman who visited over four hundred food stores weekly, and in Louisville, Betty Cartwright, a “beauty parlor operator,” paid close attention to her customers, who, according to the OWI, were “chiefly from the middle and lower classes.” A San Francisco dentist, Dr. George M. Peters, found that his patients told him little in his office, but he thought he would “hear more” at the local YMCA.

The more than five thousand rumors the OWI catalogued in 1942 fell into three major categories.

“Anxiety” rumors were indicative of a nation worried about enemies everywhere: in Seattle, rumors spread that “the Japs are planning to blow up the water mains”; in California, rumors grew of a Japanese plot to put glass into food or to spread typhus by releasing diseased fleas into populated areas. Nazis were said to have poisoned water supplies, and there was supposedly a worker in an Illinois gas mask factory who intentionally poked holes in the masks. Barns in the Midwest were allegedly painted with identifying marks on their roofs to guide enemy bombers.

“Escape” rumors reflected people’s longing for an early end to the war or Hitler’s death. In Massachusetts, stories spread that “there will be a negotiated peace with both sides on equal terms,” and that Lloyd’s of London had placed two-to-one odds on the war being over by the end of the year.

The most common type of all, “hate” rumors, were mostly centered on bigotry toward African Americans, Jews, Catholics, and Japanese Americans. People were overheard lamenting that Jews were “running the war” and were avoiding the draft by taking drugs that induced high blood pressure. Some claimed that financier Bernard Baruch was “running the country,” while others maintained that Supreme Court justice Felix Frankfurter was the secret “power behind the throne” and asked, “What right does he have to be in American politics at all? Everyone knows he’s a foreigner!” Rumors about the motives and power of Jewish Americans found a receptive audience. In a poll conducted that summer, 42 percent of Americans agreed with the statement “Jews have too much power and influence in the U.S.”

One of the most common and virulent rumors depicted African American women organizing “Eleanor Clubs,” named after the First Lady, whose attendance at the Southern Negro Youth Council Congress in Tuskegee, Alabama, and long-standing support of a federal anti-lynching law aroused the suspicion of white Southerners. In an article in The New Republic, she argued that “we must keep moving forward steadily, removing restrictions which have no sense, and fighting prejudice.” The First Lady denied that she was “agitating the race question,” maintaining that “the race question is agitated because people will not act justly and fairly toward each other as human beings.”

White women in Virginia Beach, nervous over the supposed existence of such clubs, thought their ultimate aim was “to have all white women doing their own work by October 1.” That sentiment was also heard in Pensacola, Florida, which saw the “Eleanor Society” organizing black domestic workers to decline work “in order to force white ladies into their kitchens.” Allegedly, the clubs’ motto was “A white woman in every kitchen by 1943.”

In Texas, a white woman reported trying to hire a black domestic worker for $1 per day and claimed that the worker countered with a price of $12.50 per week, warning that “when Mr. Hitler won the war, the white people would be working for the Negroes and at less wages than $12.50 per week.” Another Hitler reference came from Mississippi, where a black domestic worker was rumored to have told her white employer, “I’m waiting on Mr. Hitler. When he gets here, I won’t have to wash for you, but you’ll have to wash for me.” In South Carolina, the fear of what black domestic workers might do was so pervasive that Governor Richard Jefferies ordered state police to scour every county for reports on “Eleanor Clubs.” While no evidence was found, the police reported that “the white people appear to be considerably disturbed” over what they were hearing about the clubs. In Atlanta, the FBI tried without success to verify the existence of the clubs, and a housewife in Birmingham worried that if “Northern people” did not quit “overpaying” African Americans and “hiring them for work that white people could do,” eventually “we’re going to have a war that’s worse than Hitler’s right in our own backyard.”

Angry African Americans were also said to be supporting the enemy. According to one rumor, a black woman in Alexandria, Virginia, who refused to sit in the back of a bus told the driver, “I’ll be glad when the Japs win. Maybe we Negroes will get some consideration then.” Two black soldiers in Alabama, evidently confident of an imminent Nazi victory, were even said to have entered a “whites only” restroom.

The OWI’s Rumor Project exposed a society deeply worried about the war’s radical possibilities. Just as African Americans complained about having to fight for democracy while being denied it at home, white Americans fretted over whether the war might threaten white supremacy. The rumors resembled those that circulated at the end of the Civil War and during Reconstruction, when former slaveholders warned of the violence, sexual depravity, and social revolution that was sure to follow the end of slavery. In 1942 one often heard in Alabama that “the federal government is going to try to use Negroes in the Army…to subdue the South and impose a second Reconstruction.” In many areas of America, fear of losing the war was sometimes secondary compared to the fear launched by the frightening possibility of African American equality.

Eleanor Roosevelt figured in many other wartime rumors, such as those about her alleged Jewishness and her Communist ties. Nor did they end there. Mary Tappendorf, a member of a group called We, the Mothers, was “aghast” at the idea of women serving anywhere near the front lines. “What do they want with girls on the front line?” Tappendorf demanded. “I’ll tell you—sex!” She said the idea came from “Mrs. Eleanor,” who was leading a wider effort, encouraged by military leaders, to unleash the sexual energy of young soldiers: “They teach it to the boys in the army. They tell them they’ll go insane without it.” Meanwhile, others thought they knew the real reason some women were intent on joining the military. Rumors spread that the WAAC and WAVES were havens for lesbians.

A common misperception is that rumors are usually spread by uneducated and uninformed people. On the contrary, the OWI’s studies in New Brunswick, New Jersey, and Portland, Maine, showed that people considered “well informed” repeated rumors 63 percent of the time, whereas those considered “poorly informed” did so just 25 percent of the time. People with college degrees were more prolific rumormongers than those with high school diplomas, and those who had “active social lives” were twice as likely to repeat rumors than those who led secluded lives. Students at Harvard and Radcliffe were polled about how they formed their opinions before and after FDR gave a speech attempting to refute the rumors about the damage inflicted at Pearl Harbor. Twenty percent responded that even after hearing the president and reading official reports, in a time long before the internet and social media, they still relied on “rumor, confidential information, and inference” as the primary basis of their opinions.

Despite their best efforts to combat rumors, the OWI and local rumor clinics found that even after being presented with the facts, people who were susceptible to rumormongering often stood solidly behind those rumors. Efforts at educating large numbers of people influenced by rumor proved futile.

By 1943, once it became clear that efforts to dispel rumors were only helping them proliferate, the rumor projects were closed. Those involved in the project determined that America in wartime “has built up little or no immunity” to rumor.

Excerpted from The Year of Peril: America in 1942 by Tracy Campbell, just published by Yale University Press. Copyright © 2020 Tracy Campbell. Reprinted by permission of Yale University Press.