Among the heroic nudes, a white marble bust of an African woman, produced by the studio of French sculptor Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux in the late nineteenth century, is set to be installed in the skylighted Carroll and Milton Petrie European Sculpture Court at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in early 2020. The inscription on its pedestal chides, Pourquoi! Naître Esclave! or Why Born Enslaved!, a title that neither exonerates nor points directly at the viewer as it calls attention to the moral debt of slavery and its repercussions. The figure’s bare torso is constricted by rope with her breasts exposed, an undeniable reference to her enslavement and, possibly, torture that places this work in a context shared by overtly abolitionist objects like eighteenth-century English potter Josiah Wedgwood’s slave medallion. As little is known about the woman who modeled for Carpeaux, including whether she chose to sit for his sketches or was coerced, it also can only be guessed whether she consented to her image being used in this way.

This unknown woman’s likeness first appeared in plans for one of four figures representing the continents of Europe, Africa, Asia, and the Americas in the Fontaine de l’Observatoire in the Luxembourg Gardens in Paris. Carpeaux explained his vision in a letter to critic Ernest Chesneau: “The earth turns! I therefore represented the four cardinal points turning, as if to follow the globe’s rotation.” Carpeaux’s vision was grand in imagination but limited by experience. His original sketches featured archetypes he hoped to represent: he drew Europe with long, flowing hair and the Americas’ braid adorned with feathers, but he had no context for the faces of figures representing Asia and Africa and needed to seek out models for his designs.

Why Born Enslaved! was popular and widely reproduced in its time and continues to be cited by contemporary artists. In 2006 Kehinde Wiley produced After La Negresse, 1872, the bust of a young athletic Black man both draped in and constrained by a Los Angeles Lakers jersey. In a 2017 exhibition on the Greek island of Hydra, Kara Walker included a piece featuring a white plaster mask cast from the face of one of Carpeaux’s sculptures, lit in an alcove by a votive candle.

Despite these recent references, the Met’s recent acquisition of the marble was unusual because it already owned a copy of the work in terra-cotta. Sarah E. Lawrence, the Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Curator in Charge, European Sculpture and Decorative Arts, explained how the marble version showed Carpeaux’s evolved understanding of the figure: “When you look at the terra-cotta next to the marble, the marble actually is a very different work of art. That in carving it, the artists—and I use a plural there because it’s Carpeaux and the shop—were really doing something very particular that differentiates it from both the other marble and from the terra-cottas.”

The other marble version, titled La Négresse and dated 1868, is on display at the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek museum in Copenhagen. The Met’s version, completed five years later, reflects a finessed approach to the woman’s countenance, her expression revealing greater complexity—a mix of anguish, fortitude, and softness. Carpeaux knew the attention the work generated meant that it could be lucrative, so he sanctioned reproductions of it in less expensive forms like clay and plaster, allowing for its broad distribution. Lawrence said, “The terra-cotta is useful, to see what happens with its multiplication, where the expression of the individual is a bit diluted—I would say flattened, and much more generally accessible and appealing, because it doesn’t have the intense confrontational quality of the marble.” Carpeaux’s careful attention to the complicated expression on the woman’s face, a kind of attention typically afforded to persons of stature, is more nuanced than his rendition of Dante’s Ugolino pondering the sacrifice of his sons, another work of his that sits in the gallery. The position of the figure’s face is also curious—it is not clear whether she is turning away from the sculptor, toward those who brought her to his studio, or in another direction altogether. In any case, her discomfort is obvious. For those who see themselves tied to the legacy of moral failure represented by a Black woman bound, a sense of shame may inform their act of witnessing. Compassion may be provoked, in part, by the detail with which the figure’s countenance has been realized, conveying a disposition that is vital and searching. Even in the resin and fiberglass replicas of the work sold on eBay and Amazon today, something elemental in her mien insists on recognition.

The perception of an object’s value often depends on what is deemed to be in good taste in context. Cicero offered a word for it: “The Greeks call it prepon; let us call it decorum or propriety.” Cicero’s idea of decorum is rooted in a relationship between the speaker and their audience. By definition museums present works, and decorum is a factor in what they put on exhibition and the audiences who come to see it. According to Daniel Kapust, a professor of political theory at the University of Wisconsin, decorum is more a matter of judgment than rules, and it is intimately involved with meeting the expectations and desires of one’s audience.

While approaches to holding and displaying pieces vary according to the priorities of each museum’s collection, visitors to those museums do not share an understanding of decorum or a set of rules for engagement with objects; instead they are likely to hold their own views on what is expected or what is acceptable based on their experiences. Multiple histories exist within a single object, but which ones come to the fore depend on the context. Consider the example of a French sugar bowl, c. 1780, made of white porcelain with a blue and green leaf pattern, its rim trimmed in gold. The object, in discreet display, reflects an economy where sugar holds a prominent place on the table. The mouth of the bowl is wide, suggesting the ease and speed with which it might be replenished. But for those concerned with the more brutal aspects of the economy that made sugar available to so many households in the late eighteenth century, the sugar bowl and its related tableware might also be read as proof of the ruse of civility in the domestic sphere in order to distract from, if not obscure, the brutality of the transatlantic slave trade, which made this luxury accessible. Is a sugar bowl worthy of regard only for what its design reveals about a culture? Or for the contradictions it illustrates between that culture’s stated commercial, religious, and moral convictions? It depends on how one remembers the value of sugar in proportion to the costs of acquiring it. The ability to understand the significance of the sugar bowl depends as much on the foreknowledge of the viewer as it does the frame of reference.

Traditional museums shape the histories of power through the display of rare objects that can’t be accessed elsewhere and help us assemble the texture of cultural memory. But the singular works or artifacts that can expose unchecked histories of violence and subjugation might not be sufficient to address the gaps in any collection.

As museums face increasing pressure to be responsive to historical intersections and contradictions in their presentation of works, it can be risky to introduce audiences, who otherwise might not seek complexity born out of conflict, to objects that may provoke embarrassment or pain. Yet some institutions still believe generating this tension is a necessary step toward reconciliation. Perhaps there is no more powerful feeling provoked by a museum than shame, which extends beyond the initial encounter with an object and allows for an extended moment of recognition. Shame emerges when we are no longer confident in the stories that define us, when we are not proud of the things we have done, when we are no longer certain of the value of the things we have acquired. It can inspire leaps in compassion, as one calculates one’s own debts accrued through past misperceptions.

News about museums reconsidering their values abounds in recent years, making clear how complex relationships can be between funders’ financial interests and public expectations for moral transparency. The most notorious recent example involves Purdue Pharma, the maker of OxyContin, and the members of the Sackler family who own the company. The Louvre removed the Sackler name from one of its wings in July 2019, and both the Met and Guggenheim announced they would no longer accept donations from the family. In the summer of 2019 Warren B. Kanders, founder of Safariland, a maker of tear-gas canisters used against migrants by U.S. Customs and Border Protection officers at the San Diego–Tijuana border, stepped down from the Whitney Museum’s board of trustees after numerous artists pulled their work from the Whitney Biennial to protest his role at the museum. Complex relationships can also make it difficult to address historical errors in the collections while courting financial support for those collections.

A 2018 report commissioned by French president Emmanuel Macron and written by French historian Bénédicte Savoy and Senegalese economist and writer Felwine Sarr, recommended with unprecedented firmness that all art objects in French public museums that had been taken from Africa should be returned permanently. In recent months, prominent barrister Geoffrey Robertson has demanded the British Museum apologize for the crimes of empire and return the Hoa Hakananai’a, a moai statue, to Easter Island and the Benin bronzes to Nigeria, among other popular objects in its collection.

While protests, reports, and demonstrations aimed at institutions and benefactors have brought more candid political conversations into museum spaces, daily audiences tend not to be implicated in these conflicts; instead they are mostly encouraged to enjoy the work by whatever measures they can access. But if museums encouraged visitors to feel shame around objects carrying the legacies of colonization, slavery, theft, and discrimination, what might those exhibitions look like?

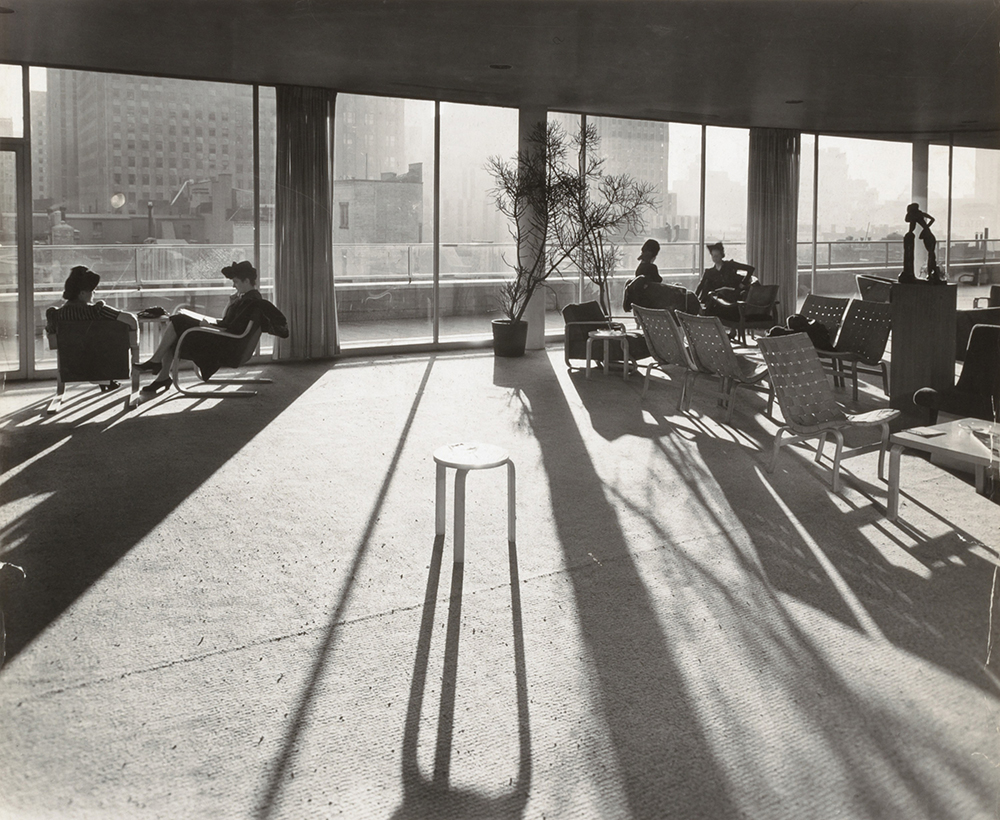

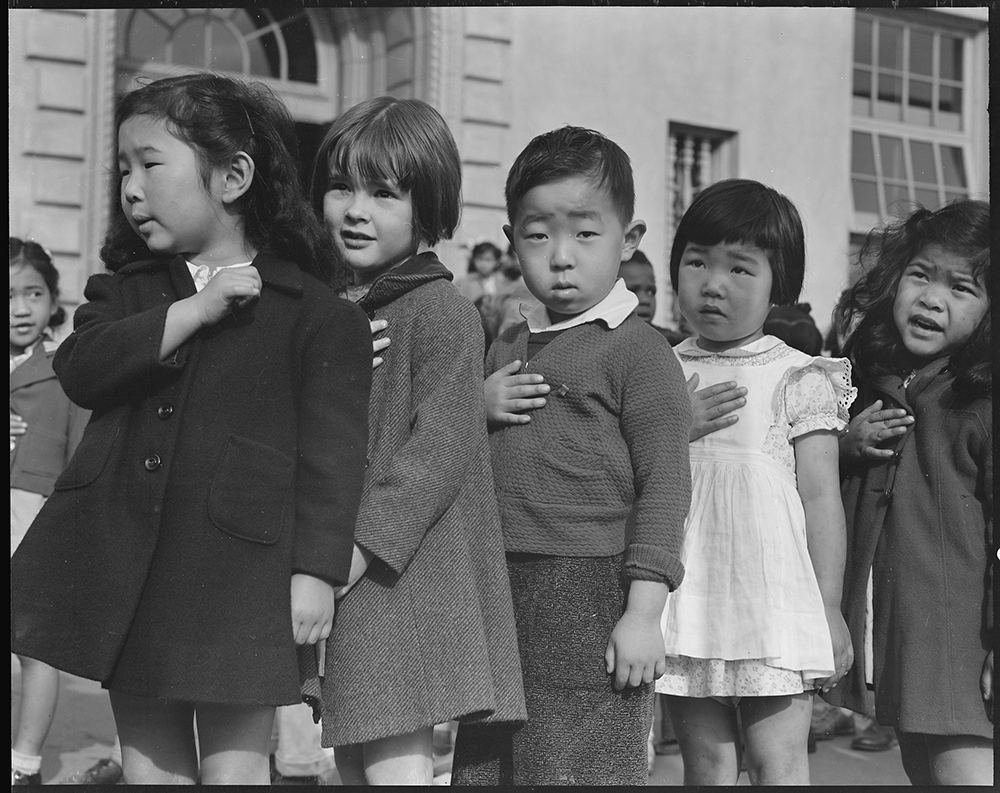

When museums ask audiences to recognize their own shame, even tacitly, for participating in systems of power that may no longer be appropriate, the dynamics can play out through personal reflection in the exhibition space. Collections that lack a sublime object able to provoke a counternarrative may need to display common objects instead. A 1970 exhibition on the experiences of Japanese Americans during World War II at Seattle’s Museum of History and Industry provides a pointed, early example of this mode of engagement. Initiated by the Seattle chapter of the Japanese American Citizens League, the Pride and Shame exhibition chronicled nearly one hundred years in the lives of Japanese and Japanese Americans in the Pacific Northwest. A significant section of the show was dedicated to their wartime imprisonment. A period room replicated the interior of the barracks at one detention camp, highlighting the harshness of everyday conditions, and the show’s display text encouraged guests to reflect on how anti-Japanese racism affected those made most vulnerable by new rules of exclusion. The exhibit questioned the use of euphemisms such as “evacuation” instead of forced removal or “internment” instead of imprisonment or incarceration. Many of the 34,000 attendees of the show were of Japanese descent. But the traveling version of the exhibition eventually reached more than a hundred thousand people.

At the time of the show, some Japanese Americans considered their incarceration by the government to be too painful to discuss, and that kept them from seeking redress or reframing their experience publicly. But the exhibition was helpful in releasing those feelings of ignominy, and on November 25, 1978, a “Day of Remembrance” was observed. Japanese Americans retraced the journey from Pioneer Square in Seattle to the Puyallup Fairgrounds, where the original camps had been erected. Media coverage of the exhibit and the Day of Remembrance generated new support for reparations, and the impact was attributed in part to the accuracy of the museum exhibition.

Sometimes no object exists to assist an audience in reckoning with the history of power or the shame it provokes. Perhaps this is where the material of everyday life might better serve the point. In lieu of cultural or artistic objects, the Legacy Museum in Montgomery, Alabama, displays jars of soil gathered from hundreds of lynching sites, each one affixed with a label indicating the name of a person subjected to violence and the location of the attack. Two hundred and eight are on display at the museum at any given time. Samples have been gathered from all 370 known lynching sites in Alabama and more than four hundred sites outside of the state, which rotate on an informal basis.

The Legacy Museum is a project of the nonprofit Equal Justice Initiative (EJI), founded by lawyer and social justice activist Bryan Stevenson, who saw a clear line to be drawn between lynching, the death penalty, and incarceration. Outside the museum stands the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, which was unveiled in April 2018. Here eight hundred weathered steel rectangular boxes are suspended, each one marked with the name of a county where a lynching took place and the names of the known victims. Together they constitute a powerful reminder of the more than 4,400 people murdered in acts of racial terror.

Community-based and collaborative processes led to the design of the museum and memorial. A team at EJI began researching the history of racial terrorism in the U.S. in 2011, and in 2015 it published a report cataloguing the names of people attacked, along with the locations marked by this violence. The report’s release brought calls from concerned people across the world who wanted to search the list of names for loved ones, to practice restorative justice, and to offer assistance in designing monuments.

“We have been motivated by an idea of shame and of how shame can be a useful and even a necessary tool in affecting change,” says Jennifer Rae Taylor, a senior attorney at EJI, adding that lynching was an act of racial terror sanctioned by social conventions of their time. They were not secret events but frenzied public festivals of brutality valorized by coverage in local newspapers, though often without perpetrators named. Shame may be an appropriate opening to reckoning with this history of power, especially for those who have benefited from the spoils of this violence.

The soil-collection process began in 2015 and relied on the support of volunteers. For the first gathering, around thirty people participated. Over the next eight months another three events were held. In June 2016 over two hundred people attended, coming from counties across Alabama as well as from California and New York. “It turned into an extremely powerful experience,” Taylor says. “In some cases, the people who came to collect the soil were people who knew that they had a personal connection to a lynching. We had a person who participated in collecting soil for her father, who was a victim of lynching. But in most instances, the people who were participating don’t know themselves to have that kind of personal connection at all, but they’re interested in having a meaningful kind of experience with this history.”

The collection project makes the case that there might there be no better reference for these events than the earth itself, culled along with records that outline the infractions against those who stood upon it. The work that needs to be done, addressing the pain and shame that is shared across landscapes, can begin in any direction one looks. Volunteers fill two jars of soil from each site. This way one is available for display in the home community, to help build its cultural memory, if so desired.

“I think a lot of times, for all people probably, but I think in particular in our culture, there’s kind of an instinct to instantly turn away from anything that is unpleasant,” Taylor tells me. “And we think that shame as a response to this kind of information is a good thing, because it is a sign that you recognize that this is wrong, and you have to be willing to kind of hold that and learn from it, so that knowledge can impact your decisions from that point on, instead of instantly turning away from it and saying, ‘I don’t want to be aware of this information because it makes me feel things I don’t want to feel.’ ”

Perhaps it is in this experience of feeling things one does not want to feel, and specifically the pain of complicity and regret, that has not been cultivated enough in museum spaces. But as we try to decipher what the past has to say about the future, room by room, object by object, we can acknowledge injuries incurred in defense of morally relative notions of beauty, stability, and justice.

The appropriateness of objects is not just related to how they align with or contradict the history of power but also how we think about their value among the present historical disruptions and social reimagining. When the Getty Museum was threatened by wildfires sweeping across southern California in the fall of 2019, some remarked that its campus was one of the safest places to be, both for the collections and the people who maintain them. Its buildings’ exterior walls were designed to be fire-resistant, as were its roofs, composed of crushed stone. Though museums are often already better prepared for catastrophe than residents of their surrounding communities, it is unclear how the climate emergency will reorient what they value most about the past. We still struggle to see the consequences of our addictions to industry, often widely celebrated by collections of objects that mark achievements in craftsmanship and artistry but also in manufacturing, chemistry, and the extraction of natural resources. Perhaps at one time considerations of climate fell beyond the expected responsibilities of cultural institutions, but as our perspectives shift, we must reckon with the consequences of what we have struggled to comprehend as a species. Some of our most celebrated accomplishments in engineering and technology, such as the personal computer or automobile, also reveal our greatest failures in ethics and sustainability. Will the objects that represent our poor choices always deserve a protected space in museums? The blunt and unyielding imposition of climate change presses us toward a future without precedent, disrupting multiple histories, especially those that lauded technological innovation as evidence of success. Addressing our shared shame about these missteps may change how we prioritize objects and the values they represent.

For more on how memorialization can both evoke and evade the past, explore Memory, the Winter 2020 issue of Lapham’s Quarterly.