Les Poires (The Pears), by Charles Philipon, 1831. Wikimedia Commons, Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Long after the French Revolution of 1789, when memories of Napoleon Bonaparte’s victories were fading and the shadows of republican ideals were about to be reinstated, a new, liberal revolution took place in France. The July Revolution of 1830 brought the liberal “King of the French People,” Louis-Philippe, to power, who then proclaimed freedom of the press. Soon after, the artist and journalist Charles Philipon gathered a team of brilliant artists and founded the satirical weekly La Caricature in 1831. Immediately taking “a step too far,” he published a drawing of the king’s head, metamorphosing in four stages to a rotting poire (pear-head), also French slang for “fool” or “simpleton.” Philipon was hauled into court and, as legend has it, avoided prison by demonstrating the resemblance—of king to pear—to the jury, by means of sketching and (very likely) verbal panache. He was acquitted of the charge of defamation: a victory for the cause of satire that would trigger the continuation of further ridicule.

Having survived his trip to court over Les Poires, Charles Philipon launched a more savage satirical paper in 1832 titled Le Charivari. Honoré Daumier’s lively masthead for Le Charivari presents portraits of a few of the artists associated with Philipon’s early satirical papers. Banging a drum at the center is Philipon himself; the young Honoré Daumier is on tambourine (fourth from the right); Traviès, or Charles-Joseph Traviès des Villers, one of the first regular caricaturists on Le Charivari, is second from the right; and Grandville, or Jean-Ignace-Isidore Gérard Grandville, who often parodied people as animals, is far right. The same year as Philipon’s Les Poires incident, young Daumier’s drawing of Louis-Philippe as Gargantua sitting on a commode also appeared in La Caricature. He was not only arrested but also received a short prison sentence.

Meanwhile Les Poires became an emblem of resistance against authority and continued to have a needling effect, appearing in Philipon’s papers in as many annoying variations as possible. When Louis-Philippe banned the drawn image, it appeared instead in further variations, formed out of an arrangement of type (quite a feat as they would have been hand-set in metal type), thereby skirting around the ban or decree. The needling would, once again, go too far. In September 1835, the entire French free press was censored with regard to political subjects.

Despite censorship, French comic papers and their caricaturists continued to thrive. Prevented from critique or ridicule of the government or those in office, they instead critiqued French (especially Parisian) society. Le Charivari was still in operation in 1862; other papers launched included Le Rire (The Laugh) in 1895 and Le Sourire (The Smile) in 1899. This front page of Le Rire shows the German monarch Kaiser Wilhelm II (standing, with a bouquet), who in 1896 had congratulated the Boer leader Paul Kruger on a British defeat, but by 1899 had turned pro-British. He is passing off his shifting loyalty in the guise of familial affection for Queen Victoria (who is, in fact, his grandmother).

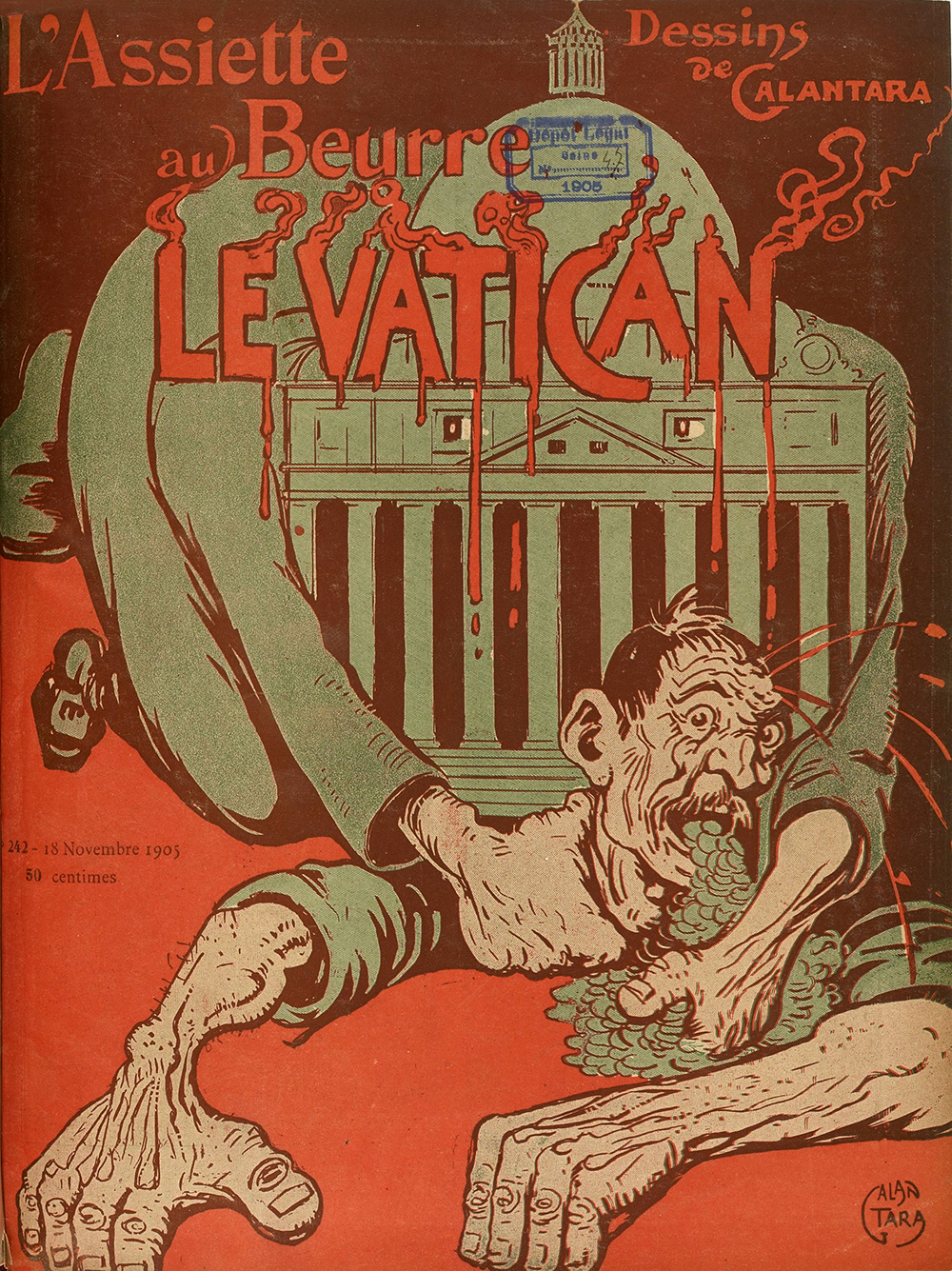

Samuel Schwarz founded the satirical weekly L’Assiette au Beurre (The Butter Dish) in 1901, appropriately named for the despised members of the governmental bureaucratic machine who connived at handing out favors to ordinary citizens for a price. (The name itself is a slur about wealth, as butter was a highly valued commodity.) The satirical paper’s mission was to attack “The Butter Dish” and the ruling classes, as well as the hierarchy and influence of the Catholic Church. It did so with energy. The sociopolitical content was mainly visual; text was minimal; and its issues often included current events or international personalities, Britain being a favorite target. This vicious front-page illustration shows another favorite target: notice the Vatican building’s shifty eyes, pig’s nose, and huge, gaping mouth.

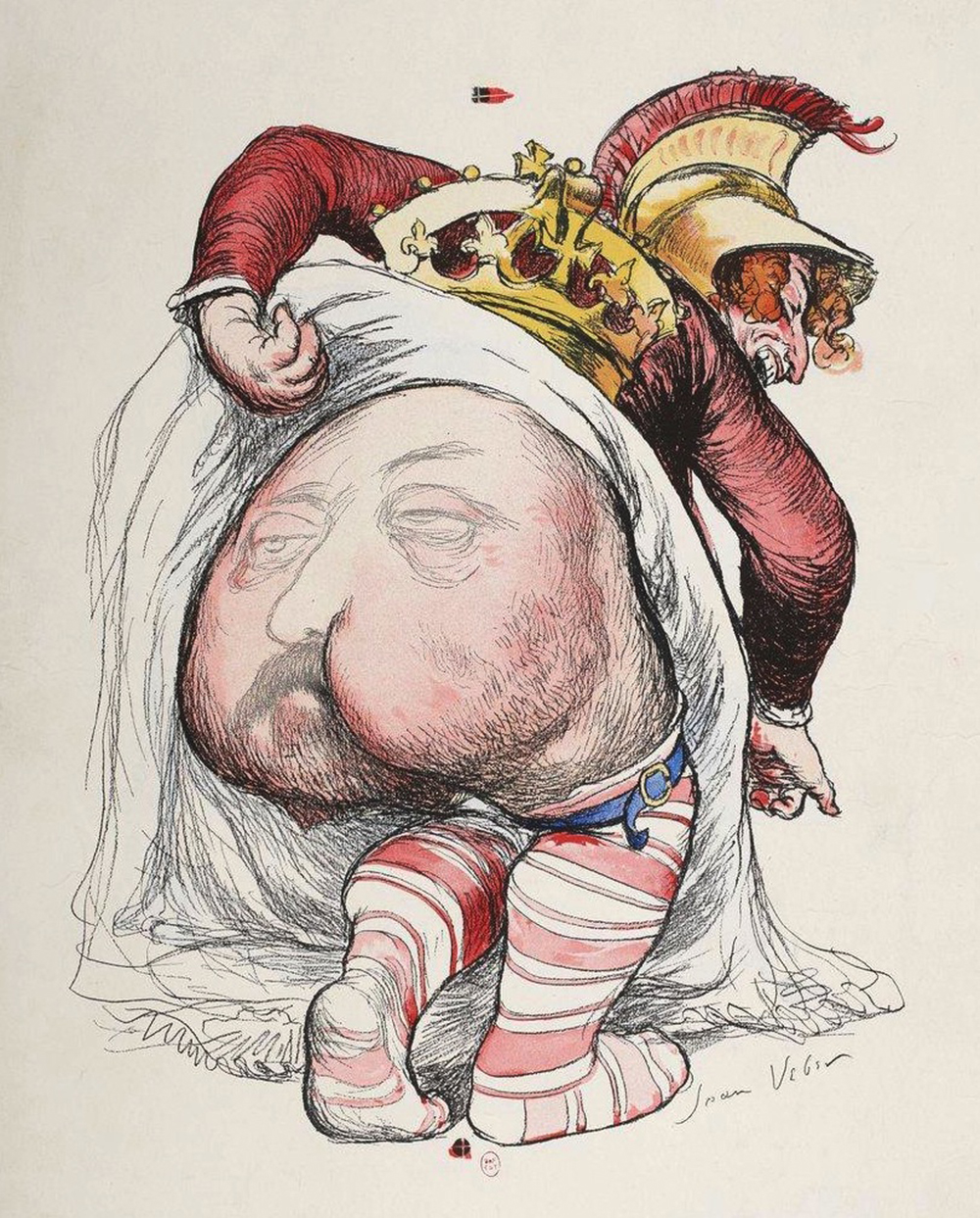

One of L’Assiette au Beurre’s most famous caricatures was produced in September 1901 by Jean Veber, who became a regular contributor. Titled L’Impudique Albion (Shameless Albion, or Shameless Britain), it features a portrait of King Edward VII imprinted on the posterior of a jesting Britannia. After years of the decorum and seriousness of Queen Victoria, who died in 1901, her heir Edward VII had a reputation for being a bit of a playboy, prone to gambling and mistresses (often located in France), and so representing a very different side of British behavior and monarchy. This French satirical tradition, particularly in its earlier, scabrous years, can be seen as having spiritual descendants in modern French satirical comics such as Charlie Hebdo, founded in 1969.

Adapted from Protest! A History of Social and Political Protest Graphics by Liz McQuiston. Copyright © 2019 by Quarto Publishing plc. Reprinted by permission of Princeton University Press.