Gathering Mushrooms in Mid-Autumn, by Utagawa Kunisada, c. 1844. The Minneapolis Institute of Art, Gift of Mrs. Charles B. Meech.

Mary Banning (1822–1903)

An unsung nineteenth-century American mycologist who, being a woman, was ostracized from the scientific community. The only mycologist who acknowledged her was Charles Horton Peck, to whom she wrote, “You are my only friend in the debatable land of fungi.”

In a mostly mycophobic country, Banning’s interest in fungi was another strike against her. Her fellow Marylanders called her the Frog Stool Lady. Individuals who saw her hunting for mushrooms in the woods would remark to each other, “Poor thing’s gone clean mad.” Her own comments about hunting for mushrooms indicate that she had not gone mad but possessed both a discerning and an aesthetic attitude toward her subject. Here’s one of those comments: “The mycologist may well liken himself to a pioneer wandering through a land filled with alternately beautiful and fantastic shapes.”

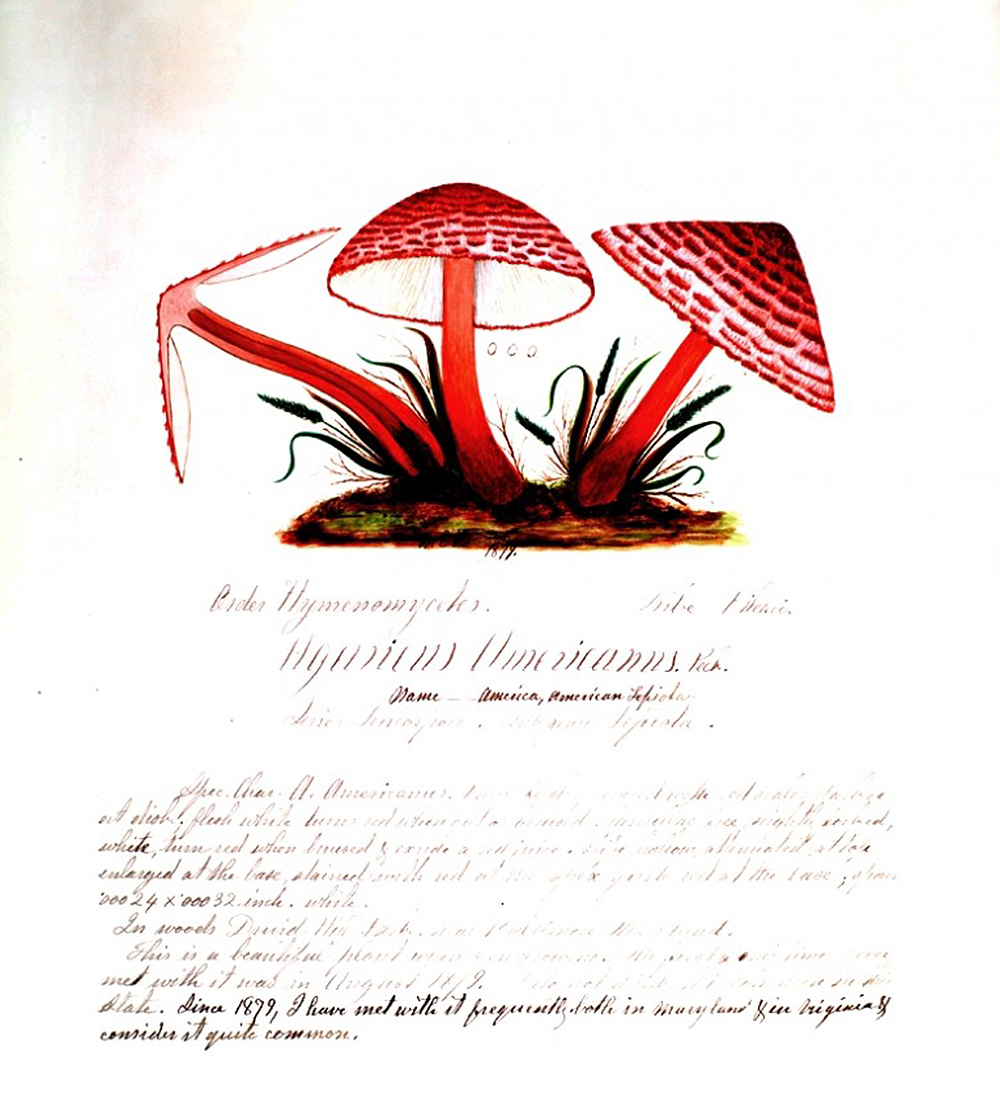

Ms. Banning described twenty-three previously unknown species of fungi and wrote a book titled The Fungi of Maryland, which remains unpublished. Like Beatrix Potter, she made very attractive paintings of mushrooms.

Carolus Clusius (1526–1607)

The Latinized name of Dutch botanist Charles de l’Ecluse. Clusius was a botanist who popularized tulip breeding in his country, but he was also a mycologist several centuries before the word was invented. His Rariorum plantarum historia is the first book devoted more or less to fungi; a sizable portion of its information reputedly came from Clusius’ chats with so-called herb women, wise women, and root women. Published in 1601, it contains watercolors probably done by Clusius’ nephew.

Rariorum plantarum historia laid the ground for the future scientific study of fungi in Europe, including Flemish priest Franciscus van Sterbeeck’s Theatrum fungorum, a tome that’s devoted not only to fungi but also to potatoes because (it’s been suggested) Sterbeeck thought potatoes were akin to truffles—after all, they grow underground. So they deserved a place in his tome.

Before Clusius’ book appeared, references to fungi in books hardly did more than offer advice as to which species were edible and which ones could cure an ailment. Those that were neither edible nor medicinal would often be described as “excrescences.” Admittedly, Clusius himself called species that weren’t edible noxii et perniciosi (noxious and pernicious).

Clusius acquired his interest in fungi by kicking around puffballs as a kid.

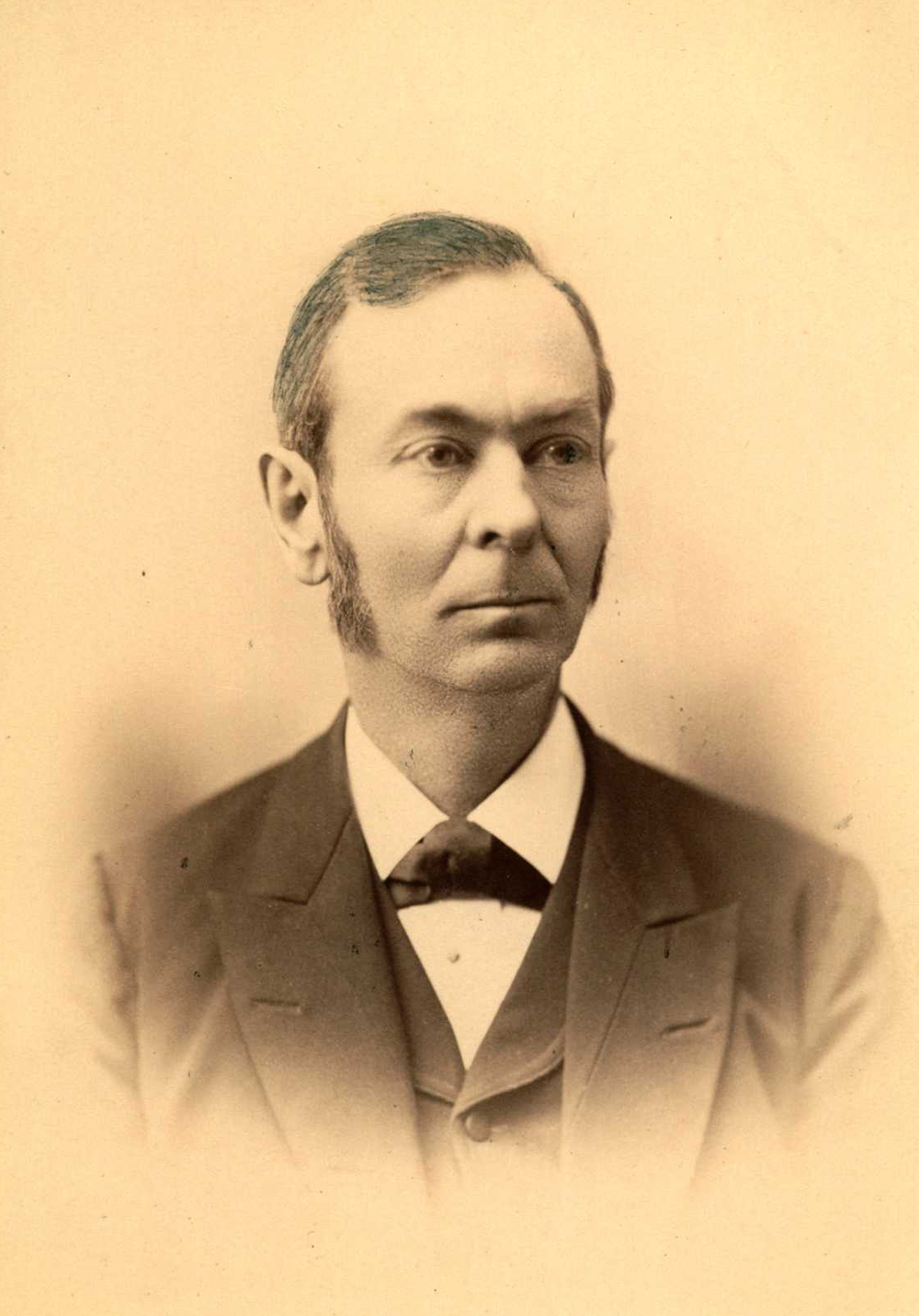

Charles Horton Peck (1833–1917)

Often referred to as the “Father of American Mycology,” although he was (like most mycologists in his day) regarded as a botanist. During his forty-eight years as New York state botanist, he described between 2,500 and 3,000 species of fungi. Several species have subsequently been named in his honor, including the so-called bleeding tooth (Hydnellum peckii) and the bolete Butyriboletus peckii.

Peck may have been the first person to climb Wright Peak in the Adirondack Mountains, but—unlike many other climbers—he made the climb not to be the first to reach the summit, but to study the fungi and plants en route to that summit. He was also the only mycologist of his day to acknowledge Mary Banning’s work with fungi. All the others turned their noses up at her because she was a woman.

A devout Presbyterian, Peck didn’t drink, smoke, or—even when he found himself unable to identify a fungal species—curse.

Phallus impudicus

An upright stinkhorn with a small hole at the top of its greenish gleba (the mucus-like coating on the cap) whose Latin binomial means “shameless penis.” In his 1597 Herbal, English botanist John Gerard called it “the pricke mushroom.” Upon seeing a specimen, Henry David Thoreau wrote in his Journal: “Pray what was Nature thinking of when she made this? She almost puts herself on a level with those who draw in privies.” But if Phallus impudicus is offensive to our species, it’s irresistible to various flying insects, which, attracted by its carrion-like odor, land on the gleba and carry off its spores, thus taxiing them to a new locale.

Not surprisingly, P. impudicus has inspired plenty of folklore. In the Ozarks, adolescent girls reputedly used to take off their clothes and dance around specimens on the assumption that this activity would get them virile boyfriends; in Sarawak, the Iban believe it’s the penis of an enemy warrior slain in battle and tend to give it a very wide berth, lest it seek posthumous revenge on them; and in several African countries, the gleba is spread on young women to make them fertile. Given the erectile strength of P. impudicus, these seemingly far-fetched notions may have a certain wisdom—specimens have been documented thrusting through asphalt with a lifting power of over eight hundred pounds.

Here I might add that the sight of a P. impudicus specimen in a Reykjavik cemetery drew this comment from an Icelandic friend of mine: “Oh well, he died happy.”

Maria Sabina (1894–1985)

A Mazatec curandera (shamaness or healer) from the Mexican state of Oaxaca, Maria Sabina used Psilocybe mushrooms in her rituals. She called these mushrooms her “saintly children” and reputedly had intimate conversations with them. She requested that her clients eat them in pairs so as to reflect the balance of masculine and feminine. Other Mazatecs called the same mushrooms los pajaritos (little birds).

In June 1955, the American ethnomycologist Gordon Wasson paid Maria Sabina a visit, ate some of her mushrooms (Psilocybe mexicana), and then wrote a seventeen-page article titled “Seeking the Magic Mushroom” for Life magazine in 1957. This article inspired numerous hipster types to beat a path to her door. Such rock celebrities as Mick Jagger, John Lennon, Keith Richards, and Bob Dylan all seem to have visited her. Joined by Wasson, Swiss scientist and LSD concocter Albert Hofmann paid her a more scientifically inspired visit in 1962.

Perhaps not surprisingly, Maria Sabina felt that her children had lost their saintliness after “the coming of white man.”

Walter Snell (1889–1980)

A mycologist and major league baseball player. In the latter capacity, he was one of five catchers used by the Boston Red Sox in 1913. Subsequently, he became both head baseball coach and a professor of mycology at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island.

In addition to studying tree diseases and decay in building timber, Snell specialized in boletes. In 1941 he married another bolete expert, Esther A. Dick, and began coauthoring papers with her. In 1957 they cowrote A Glossary of Mycology. They also cowrote the highly regarded monograph The Boleti of Northeastern North America.

You could argue that Snell’s mycological batting average was considerably better than his baseball one, for “Wally,” as Snell was called in his baseball days, had a batting average of only .250 in the big leagues.

Excerpted from Fungipedia: A Brief Compendium of Mushroom Lore by Lawrence Millman. Copyright © 2019 by Princeton University Press. Reprinted by permission.