A curious anecdote, part romantic tragedy, part macabre art history, is recorded in Xijing zaji (Miscellanies of the Western Capital), referring to events during the Early, or Western, Han dynasty (206 bc–9):

Since there were many girls in Emperor Yuan’s harem whom he had not been able to meet, he ordered artists to sketch them. According to these sketches he summoned them to be favored. All the palace girls bribed the artists: some gave as much as 100,000 cash, and none less than 50,000. Only Wang Qiang [Wang Zhaojun] was unwilling to give. Therefore, she was not able to meet the emperor. Later a Xiongnu envoy came to court seeking a beauty for his queen. Thereupon the emperor, basing his opinion upon the sketches, selected [Wang] Zhaojun to go. When she was about to leave, he summoned her and saw that her beauty was foremost in the harem. Her replies and deportment were genteel and decorous. The emperor regretted her selection, but since the list of names was already set and the emperor felt it important to maintain credibility with foreigners, he did not change girls. The matter was then thoroughly investigated, and the artists were all sentenced to be executed and to have their corpses exposed in the marketplace. Their confiscated homes and properties all were worth millions. Among the artists there was a Mao Yanshou of Duling who painted human portraits. Whether ugly or beautiful, old or young, he always attained a true likeness…They were all executed and their corpses exposed in the marketplace on the same day. Thus the number of artists in the capital dwindled.

This account is drawn from a text that may have been compiled only in the early sixth century, but it includes figures recorded in earlier official histories, including Emperor Yuan (r. 48 bc–33 bc) and Wang Qiang, or Zhaojun (53 bc–18), who was married to a foreign Xiongnu ruler and bore him children. The story of the neglected woman in the imperial harem whose beauty was only recognized after she had been promised to a nomadic ruler was mixed with fictional elements in popular culture and literature. Whether historical or fictional, these narratives point to some recurrent elements in the cultural status of portraiture in China involving both gender and foreign relations.

Like Bridal Du in the Peony Pavilion, Wang Zhaojun, sequestered in the imperial harem, was in some ways invisible without her portrait, but rather than fashioning her own image she relied on a portraitist’s mediation. The truth of and in portraiture is centrally at issue, as the narrative suggests that her portrait was disfigured or made unflattering by the painter Mao Yanshou. Portraits as substitutes for firsthand experience of the harem women held a crucial image-making power that could be manipulated by court portraitists to enhance their own or the subject’s fortunes, or distorted with tragic consequences for all. Beyond the personal level, portraiture could impact matters of state in terms of imperial bloodlines and succession, or alter the course of foreign relations, since Wang Zhaojun bore two sons to the ruler of the northern rival Xiongnu regime, though neither succeeded him. The extreme punishments suffered by the court painters who participated in the extortion and bribery scheme recorded in the anecdote further illustrate the gravity of their offense and the value placed on truthful representation in court relationships.

Wang Zhaojun was often represented pictorially in much later times as a tragic exile from her homeland, traveling mournfully to her new life across the harsh conditions of the northern frontier. Other imaginary portrayals suggest her political role and imagistic place in intercultural and foreign relations. A twelfth- or thirteenth-century woodblock print of Four Beauties, with a caption suggesting their capacity to overturn empires, includes a labeled image of Wang Zhaojun, who alone holds a brush and scroll as if she might be writing to request a return to China, as she was reputed to have done without success. A cartouche identifies the print as the product of the Ji family of printer-publishers, active under the Jurchen Jin regime that conquered and occupied north China in the twelfth and early thirteenth centuries. The print was archaeologically recovered in Khara-Khoto in western Inner Mongolia, a region ruled in that twelfth- to thirteenth-century era by the Tanguts as the Xi Xia empire. The discovery of the print in this location, within that historical context, is thus evidence of the broad circulation of print images as carriers of Chinese popular culture into neighboring regions.

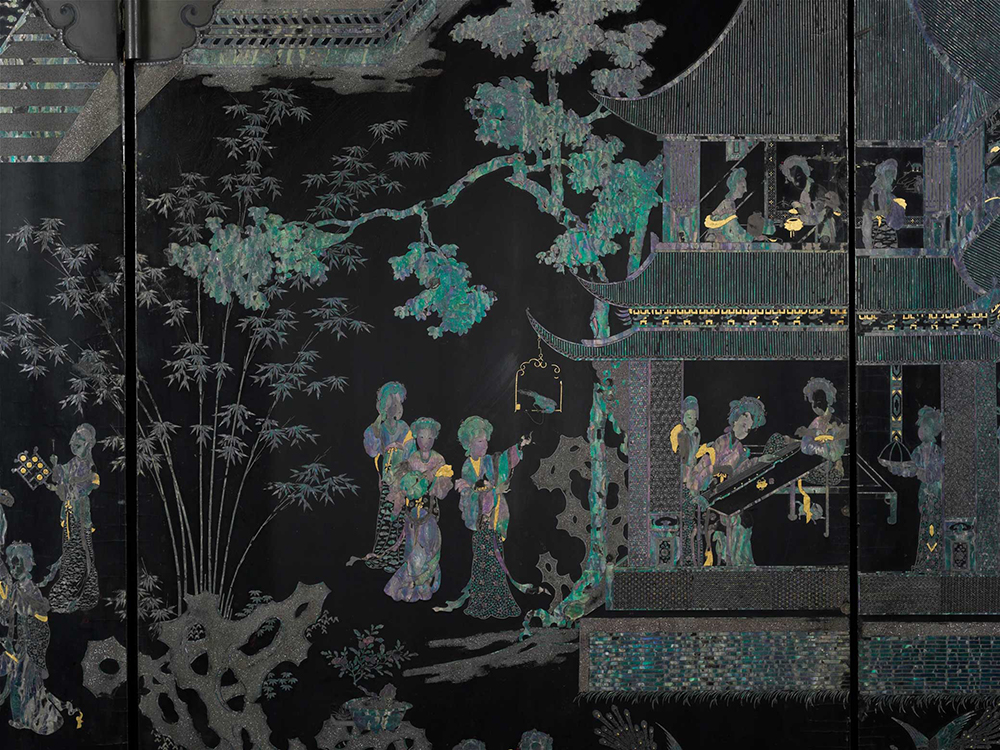

The Wang Zhaojun story remained popular in Ming dynasty (1368–1644) publications and performance culture based on more recent operatic versions that emphasized Zhaojun’s loyalty to Han mores and her rejection of nomadic customs. In a long handscroll known as Spring Dawn in the Han Palace the Suzhou professional painter Qiu Ying (c. 1494–1552) visualized an opulent imaginary court life that evokes some elements of the Wang Zhaojun narrative in its depiction of a court painter portraying aristocratic women. Qiu’s unusually detailed description of the portrait process includes the facing positions of the portraitist and a high-ranking consort who is framed by a painted screen, along with pigment dishes and an inkstone on the artist’s table. The portrait emerging beneath the painter’s brush on a framed panel in this case faithfully mirrors the subject’s appearance. Groups of palace women at either side are bracketed by columns into further screen-like arrangements, and all the figures are open to visibility and displayed on a raised platform suggestive of a theatrical stage.

In an adjacent scene to the right a palace woman standing in the center of a similarly framed and elevated hall inspects the bust-length portrait held up before her as if confronting her mirror image. The interplay of faces and gazes of the attendants and companions surrounding the portrait image and the blank side of another painting panel further confuse the status of the “real” and the represented. The vignettes to either side, of women playing a board game and ironing a length of silk cloth, are reproductions of a different order, as visual quotations from famous early figure paintings from earlier dynasties. Still another kind of reproduction is implied by the male children playing near their mothers, who might be understood as the products of the emperor’s selection of a partner based on her portrait.

Marriage alliances as instruments of foreign relations also figure in The Imperial Sedan Chair, a horizontal scroll attributed to the seventh-century Tang dynasty court painter Yan Liben (c. 600–673). It depicts an envoy sent from Tibet in 634 to negotiate a marriage alliance with the Tang emperor Taizong, who agreed to give his adopted daughter Princess Wencheng to the Tibetan ruler in a marriage realized in 641. The extant painting is likely an eleventh-century copy that preserves iconographic and stylistic features of an original Tang dynasty work. The composition stages the encounter between the Tibetan emissary Ludongzan, dressed in a distinctive, richly patterned long brocade robe, with Taizong (r. 626–49), who is seated on a sedan seat carried by a retinue of palace women, while others carry large fans and a parasol-like canopy held above the emperor as portable signs of rank. The presentation of Taizong’s figure in three-quarter view is consistent with other imperial portraits attributed to Yan Liben, who was recorded as having painted portraits of Taizong and of foreign kings and envoys who sent offerings to his court in 642. The unseen focus of the event is Princess Wencheng, who like Wang Zhaojun remains hidden while still acting as the bridge between Chinese and Tibetan regimes and cultures. The group portrait served as visual authentication of the diplomatic audience that initiated the alliance, as a kind of pictorial marriage contract.

Marriage, diplomacy, power, portraiture, and piety were at times densely intertwined at the Mogao Grottoes, the Buddhist cave temple complex at Dunhuang in present-day northwest China. Dunhuang was a crossroads for merchants and pilgrims traveling the overland Silk Road routes between China and central and western Asia. The region also had a complex political and cultural history, including a period of independent rule of powerful local generals and families with little more than nominal allegiance to Chinese dynastic authority. Under such circumstances strategic alliances with neighboring regimes were all the more important, as documented in caves sponsored by Cao Yijin, who took power in the Dunhuang region in 914 as commander of a “Return to Righteousness” army. A mural painting in Cave 98 in part commemorates the alliance marriage in 934 of Cao’s second daughter to the king of Khotan, Li Shengtian (also known as Viśa’ Sambhava), ruler of that prosperous center of jade mining and trade from 912 to 966. The portrait of the Khotanese king, who bears a gilded incense burner and flower as if leading a pious procession, was painted over an earlier mural sometime after 940 as a way of asserting his status as donor of the cave, in place of the actual sponsor Cao Yijin, who died in 935. The imposing figure of Li Shengtian is almost ten feet high, including a tall openwork crown encrusted with nephrite jade stones in gold settings surmounted by a parasol borne by celestial children, while goddesses support his feet, all signs of the Khotanese king’s semi-divine status. He wears robes decorated with dragon designs in the Chinese imperial pattern and a massive sword as symbols of his terrestrial power. As with most donor portraits from Dunhuang his face seems more generally idealized than specific, but his thin nose and long eyes may have been marks of his ethnic identity. His bride’s similarly ornate crown with pendant jade branches and her ropes of jade necklaces also reference the mineral source of Khotan’s wealth and influence. Her face is obscured by damage to the wall surface, but both portraits were likely painted by members of a local Dunhuang painting academy established by her ruler-father Cao Yijin. Other portrait figures in the cave wear Uyghur costumes, reflecting Cao Yijin’s own earlier alliance marriage to a princess of that neighboring regime.

Portraits could serve other diplomatic purposes beyond documenting or facilitating alliance marriages. The founding emperor of the Song dynasty, known as Taizu (r. 960–76), dispatched his court painter and portrait specialist Wang Ai to Nanjing (then called Jinling) to secretly sketch the portraits of three leaders of the remnant Southern Tang regime based there, which held out against Song pressure for some sixteen years before finally surrendering in 976. The subjects of the secret portraits included Han Xizai, also surreptitiously, and more famously depicted by the Southern Tang court painter Gu Hongzhong at the behest of his own ruler. In 988 the founding Song emperor’s brother and successor Taizong (r. 976–97) ordered Mou Gu, another portrait specialist, to accompany envoys to the region of modern Vietnam, an independent state since 939, where he remained for several years and painted portraits of the local king and his ministers. In 1053 Emperor Xingzong (r. 1031–55) of the Khitan Liao empire, a northern neighboring and rival regime contemporary with the Northern Song, sent portraits of three Liao rulers to the court of the Song emperor Renzong, with a request that a portrait of Renzong be exchanged in return.

Although Xingzong died before the Song court could fulfill his request, the Song court asked that a portrait of the Liao ruler’s successor be sent to them immediately. The new Liao ruler asked the Song court to first fulfill their part of the bargain, but the Song argued that the relationship between the two regimes, although designated by their joint treaty of Shanyuan in 1004 as between equals, should be seen as equivalent to that between (Song) uncle and (Liao) nephew rather than one of full equality. The episode suggests that possession of a foreign imperial portrait, beyond questions of reciprocal gift exchange and attendant contests of higher and lower status, may have carried the aura of a talismanic object conferring power over the portrayed subject.

Reprinted with permission from Facing China: Truth and Memory in Portraiture by Richard Vinograd, published by Reaktion Books Ltd. Copyright © Richard Vinograd 2022. All rights reserved.