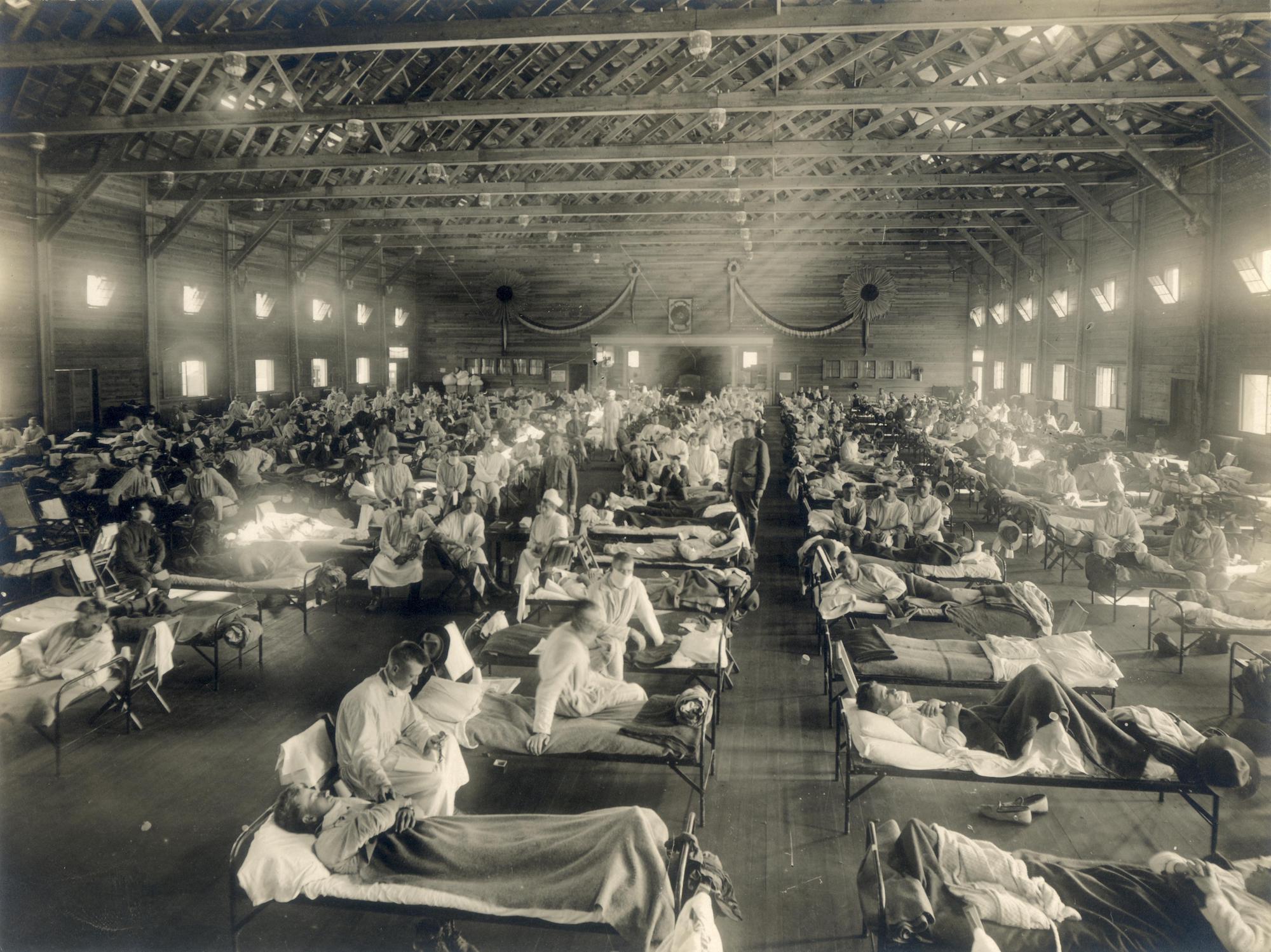

Emergency hospital at Camp Funston in Kansas, 1918. National Museum of Health and Medicine, Otis Historical Archives, New Contributed Photographs Collection (CC BY 2.0).

Nancy K. Bristow is a professor of history at the University of Puget Sound. She is the author of American Pandemic: The Lost Worlds of the 1918 Influenza Epidemic and Steeped in the Blood of Racism: Black Power, Law and Order, and the 1970 Shootings at Jackson State College.

Why don’t we start with the basics: What was the 1918 flu pandemic, and why was it so bad?

The 1918 influenza pandemic was the result of a genetic shift in the virus that causes influenza, which means that you had a new, entirely unseen virus infecting the world. They estimate that something like one-third of human beings worldwide were infected by it, and somewhere between fifty and a hundred million people around the globe perished; 675,000 Americans died. It was an extraordinarily difficult and costly event for the world as a whole and for families and individuals. In 1918 the life expectancy of Americans was lowered by twelve years. That gives you a sense of just how dramatic the impact was.

What was it about this particular moment that allowed this to happen?

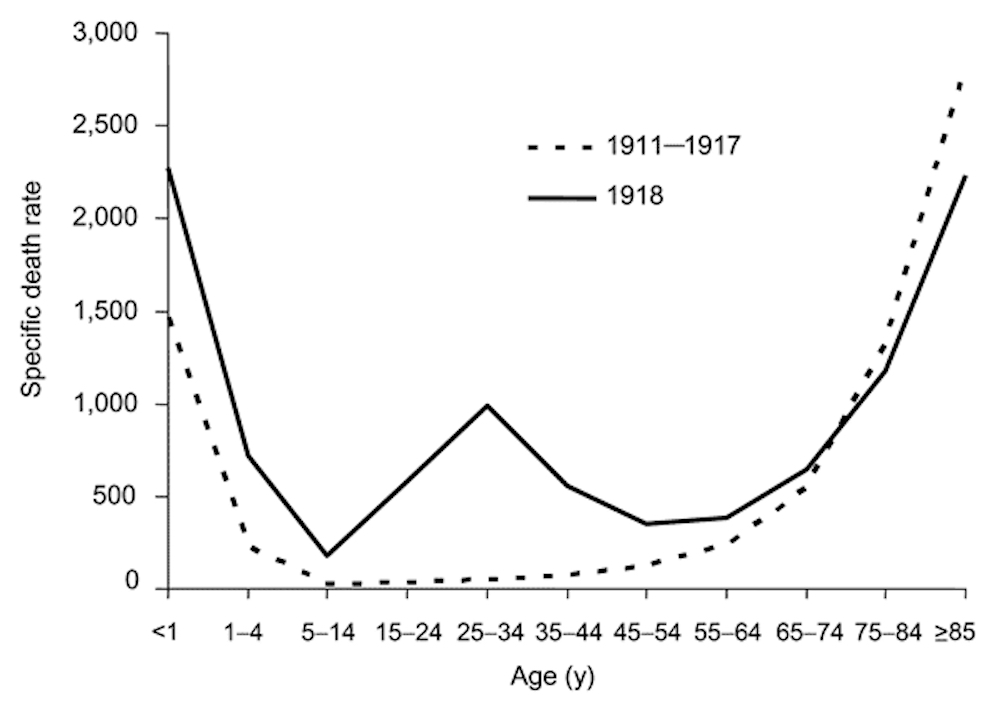

The nation was at war, and that certainly had an impact, because when the virus was first emerging, in its initial wave in the spring of 1918, American troops were being mobilized to go to Europe. Its first wave strikes in Kansas, and then travels with American troops to the European battlefields, where it moves first among the Germans and the English. Then it will move to the French soldiers, and eventually will invade the entire European continent and the civilians there. With so much of the virus out there, it’s constantly changing, and again you have what’s called a genetic shift, which is a dramatic recombination of the virus. A second wave emerges in the late summer of 1918 and explodes worldwide in three different locations within mere days: in Brest, France; Freetown, Sierra Leone; and Boston, Massachusetts. And this new virus is extraordinarily contagious, very deadly, and very unpleasant for those who suffer it, and it especially attacks young and healthy adults between the ages of twenty and forty. So the war is helping the virus move, and it is offering the virus the right conditions: people crowded in small places without sanitation or the opportunity to wash properly. It’s moving among those populations; it’s moving around the world because of troop movements. As a result, when it explodes you also have a virus that, unfortunately, is especially deadly among the very populations that in many cases are close together, the young adults, who will make up half of the fatalities in the United States. Almost 50 percent of American deaths will be among people between the ages of twenty and forty.

Traditionally influenza kills the very young and the very old, producing a U-shaped morality chart. Here you get more of a W, with a spike right in the prime of life.

Like H1N1?

Exactly.

Can you talk a little about what brought you to the study of the 1918 pandemic?

Several years ago I was backpacking with my father and my partner on the Benson Plateau in Oregon, near Mount Hood, and in an offhanded comment my dad said something about my great-grandparents dying in the flu pandemic. I just stopped dead in my tracks: “Wait, what? My great-grandparents?” I knew that my grandfather had been orphaned, but I didn’t know the context within which it had taken place, and I’d always been interested in the flu pandemic, so all of a sudden I had this personal connection. They had been working-class people, recently arrived Irish immigrants, so there was no way to find out anything about what happened to them. I know their death dates, and that’s all I could learn. So to write this book was an opportunity to try to build the world in which my great-grandparents John and Elizabeth Bristow were living, and what it meant then for their community and for their son, my grandfather, to go through what they experienced.

Can you give me a sense of what living through this pandemic would have been like? Or is there too much diversity of experience to talk about what life in the pandemic was like for Americans writ large?

On the one hand, you’re right. It is impossible to talk about an average experience. At the same time, the virus itself did not discriminate, did not recognize social class or racial identity. People who had the flu had similar symptoms: a rapid onset of the illness, very high fevers, headaches, weakness, often a great deal of pain in their muscles and joints, and congestion. Often they suffered from chills and drowsiness with total exhaustion. It would worsen for some, who would get even higher fevers and transition into a kind of delirious state, sometimes unconsciousness. There would be hemorrhaging in their lungs, belabored breathing. And for those who would go on to die of the influenza itself, rather than a secondary infection, they literally would be drowning in their own bodily fluids, leading to a discoloration of their faces and their extremities; they turned blue and black, and often they would suffer nosebleeds and a bloody cough. So, in that sense, that’s the experience. People who are caregivers, people who are family members are witnessing that particular illness, which must have been terrifying to observe. And those who suffered through it themselves were initially in a fair amount of discomfort until they would enter the more delirious or unconscious state.

But that said, the ways in which people experienced the disease varied enormously, so that you can’t say that there was an average experience of it. Caregiving and nursing mattered dramatically, even though actual medical care—the capacity to cure or to help somebody through the illness—didn’t exist; they didn’t have ventilators or antibiotics. But you could give comfort. The ability to be well taken care of, and to be able to isolate the sick, depended on having some financial resources. For the poor, and especially for poor people of color, this pandemic landed differentially, so that people suffered the illness without resources, and that could often be a very miserable state. For poor families, it might mean hunger, it might mean cold, it might mean homelessness with the loss of a breadwinner, and even going through the illness without access to nursing care. Families might have several people in the family stricken, and without anyone to help them they might even have someone who passed away who was still in their living space with them.

What about how communities dealt with the pandemic? Was that experience different all over the country as well?

It was. It varied enormously. In general, the common pattern was a lot of community commitment, and folks nationwide stepped up to do the right thing. You hear stories of schoolteachers whose school districts were closed down and were asked to serve as volunteer nurses instead. In an email from a colleague this week, I learned the story of schoolteacher who spent the pandemic holding the hands of the dying in an emergency ward. And that kind of story is not unusual. People formed soup kitchens, they helped in the emergency hospitals, they delivered food, they ran temporary orphanages to take care of children whose parents were ill. So again and again you see people doing really heroic things to help one another. And this is an era in which, because they can’t identify the virus, and they don’t really have the same kind of understanding of personal protective equipment we do now, those who offered that kind of help were often putting their own lives at risk. Across the country you see examples of communities really stepping up and of individuals stepping up to be their best selves, of being what Rebecca Solnit describes as part of “a paradise built in hell”: this idea that we can be our best selves in the midst of a catastrophe and that that’s actually a common reaction for human beings. You see that a great deal in 1918.

Certainly there were profiteers—casket makers who try to make a buck, people who are trying to get away with things because of the pandemic. But there are very few of those stories in the historical record and far more of people caring about their communities.

That’s lovely. What about from a public health perspective? Did public health initiatives across the country vary considerably?

They do, with sometimes tragic results. We know for a fact today that to engage in social distancing, to do closures early, comprehensively, and for the duration makes a big difference. This is research that’s been done in recent years by people at the University of Michigan and at the CDC. It’s very clear that social distancing in 1918 worked, and the more dramatic it was, the more helpful it was. But in 1918 the public health profession is still in its infancy, so you have a number of people with a lot of knowledge but varying levels of power in their local communities. So this is something that’s handled by states, by counties, by cities and towns.

Remarkably, because people are so anxious to have a way to take control, a way to contribute to halting or slowing the illness, people in the main wave of the pandemic—in late September, October, and November, the second wave of the 1918 pandemic—are quite willing to follow the rules that the public health people put in place. It’s only later, when another wave arrives, that people start to think, “If it worked, why is this back? So what’s the point?” When you’re in the midst it’s very hard to see the benefits of social distancing because you can’t make the comparison with what would happen if you weren’t doing those things. So in 1918 initially there’s a great deal of support for what public health people ask for; then it wanes as the third wave comes in, it wanes as business owners become frustrated with the loss of income. This frustration is understandable and why it’s so important, as we’re doing now, that we figure out ways to support those people who are losing wages, who are losing business, in the midst of the pandemic. So there is tremendous variation nationwide in terms of what different communities are able to put in place and how long they’re able to keep restrictions in place. What is clear is that those restrictions, especially social distancing and quarantining, were effective.

You mentioned the initiatives now being put in place to protect businesses—were there initiatives like that at the time as well?

No. Almost not at all. At this point the nation hadn’t developed the social safety net built during Roosevelt’s New Deal in the 1930s, when we began to acknowledge more comprehensively that the federal government has some responsibility for the financial well-being of the American people. We’d seen a little bit of that during the Progressive Era but nothing like what would be developed during the pandemic. So no, there’s not that kind of federal response. In fact there is no federal response, except for the public health service.

What about the kind of activism we’re seeing now, where people are fighting to stop the inequalities that are being exacerbated or highlighted by the current pandemic by calling for things like rent freezes or for people to be released from jail or ICE detention? Do you see activists using the 1918 pandemic to make arguments in favor of social change?

There’s very little of that, in fact. One of the problems is that the nation is at war, so there’s this notion that cooperation is part of the war effort. Those who might have been vocal at this moment, like the Industrial Workers of the World, had been silenced because of the war, so by late 1918 some of the most fervent voices for the rights of the poor and laboring people simply cannot speak.

There are examples of people pushing back. One of my favorites is a sermon given by the Reverend Francis J. Grimké from his Fifteenth Street Presbyterian Church in Washington, DC. He argues that God was trying to waken Americans to the sacrilege of the racial caste system. He says, “Every part of the land has felt its deadly touch.” And then he goes on to suggest that God is trying to show Americans “the folly of the empty conceit of his vaunted race superiority, by dealing with him just as he dealt with the peoples of darker hue.” He maintains that the pandemic was God’s attempt to upset the white supremacist hierarchy in the country. And there are certainly women who are fighting on behalf of women’s rights. It helps, surely, women’s fight for the vote that women are on the front lines of fighting the pandemic, just as they had been on the front lines serving as nurses during the war.

But to organize an acknowledgment of the inequities was very hard to do and doesn’t get a foothold. Instead the status quo is really reinforced during the pandemic, and that’s one of the great tragedies, I think.

A lot of the reform in the Progressive Era, out of which this comes, is a kind of middle-class social uplift, and so sometimes the very people who are offering aid to the poorest are not thinking about institutional change or deep reform. They’re thinking about changing individuals. There’s often a notion of the “worthy” and the “unworthy” poor, and unless you’re meeting certain middle-class standards of behavior, then maybe you’re not really deserving of aid because the problems that you’re facing are your own fault. So rather than a broad-based reform effort for institutionalized change, we see a lot of calls for “cleaning up” the poor, getting them to work, rather than recognizing the ways in which the inequities are systemic, built into the racial and class hierarchies.

Is there a story of someone’s experience during the pandemic that most stands out to you now? Something that you most clearly remember from when you were doing this research?

I actually have two.

The first is a story of a person I don’t know very much about, but I do know the bare bones of her story, which is an important one. Her name was Edith Potter. She was a fifteen-year-old enrolled at the Chemawa Indian School in Salem, Oregon. The Chemawa Indian School was only a year younger than the inaugural off-reservation boarding school, the Carlisle Indian School, and was based on the same premises—that the “Indian problem” would be solved by forced assimilation, by removing children from their families into a forced Americanization process. Her mother had agreed to send Edith from California to this school after Edith’s father died.

Edith arrived at this school in mid-September 2018 and was soon approved as a healthy student to enroll. But on October 18 the superintendent of the school writes to her home reservation and asks them to let her mother know that her daughter is quite sick. They tell her not to worry, she’s not in any danger yet, but she’s very sick with “a very bad case of the grippe.” And hers is one of over five hundred cases of influenza suffered by the children at the Chemawa Indian School that fall. Like many places, it caused the complete unsettling of the school: a monthlong quarantine and the halting of all academic work for three weeks. Edith’s story would be one of the tragedies. Just a few hours after the letter went out, they followed up with a telegram saying that though everything possible was being done, Edith was seriously ill with influenza. And the next day they sent another telegram that Edith Potter had died of influenza and would have to be buried that day. The next week they sent a letter to her mother suggesting that everything possible was done in the way of medical care and nursing and that “the sick was never left alone for one minute.” The superintendent wrote, “I feel we have done just as well as could be done.” But such news didn’t relieve her mother’s sense of loss. Edith’s mother wanted to bring her daughter’s body home for burial and was frustrated to learn that was impossible, that she would have to wait a year before she could ask again. And that’s the last I know of Edith Potter’s story, but it’s an illuminating one, illustrating how quickly this thing could happen, how devastating it was for the sick and for those who cared for them, the kind of chaos that emerged and made worse the pain of loss, and the reality that it really did matter who you were when the epidemic landed. To be a child at one of the Indian schools in 1918 was a very dangerous place to be.

The other story that really speaks to me is the story of a woman named Lillian Kancianich. And she stays with me because she’s the one person I interviewed for my book. Because of when I wrote it, it was hard to find survivors to talk with. She had been born in June 1918 in Lidgerwood, North Dakota. Her mother was seen on Armistice Day—November 11, 1918—sweeping the family’s front porch, and that was the last time she would be out in public. She took ill the next day, on November 12, and died in just five days. Lillian at this point was still an infant. Lillian’s father, because of social custom in their community, was not eligible, in a sense, to raise his two daughters without a wife in the home. It simply wasn’t done that a man would raise his own children alone. Christine, her sister, was sent away to boarding school and then went to live with relatives. But Lillian, as she described to me eighty-five years later, “just went from home to home” for two years, until she was finally settled with relatives and was able to see her dad regularly. But the impact for her was expansive: she was separated from her sister for many years, and as a child she often used to sit on the back steps lamenting that she wished she had a mother. In grade school she was asked what she wanted to be when she grew up, and her reply was that she wanted to grow up to be a stepmom—an indication of how powerfully these events of her childhood had impacted her. When I interviewed her in 2003 and asked her if she thought the pandemic had mattered in her life, she said the pandemic had “changed my life completely…It had to.” Her story sticks with me because it was so powerful to speak with this elderly woman, a happy woman with a loving family surrounding her who’d had a great life, but this thing that had happened to her as a five-month-old had stayed with her, and she had never forgotten it, even though she couldn’t remember the pandemic itself. The meaning of that event stayed with her for her entire life.

Those stories give a good sense of what this pandemic could mean to one person. What do you think was the most profound impact of the pandemic on the United States as a whole?

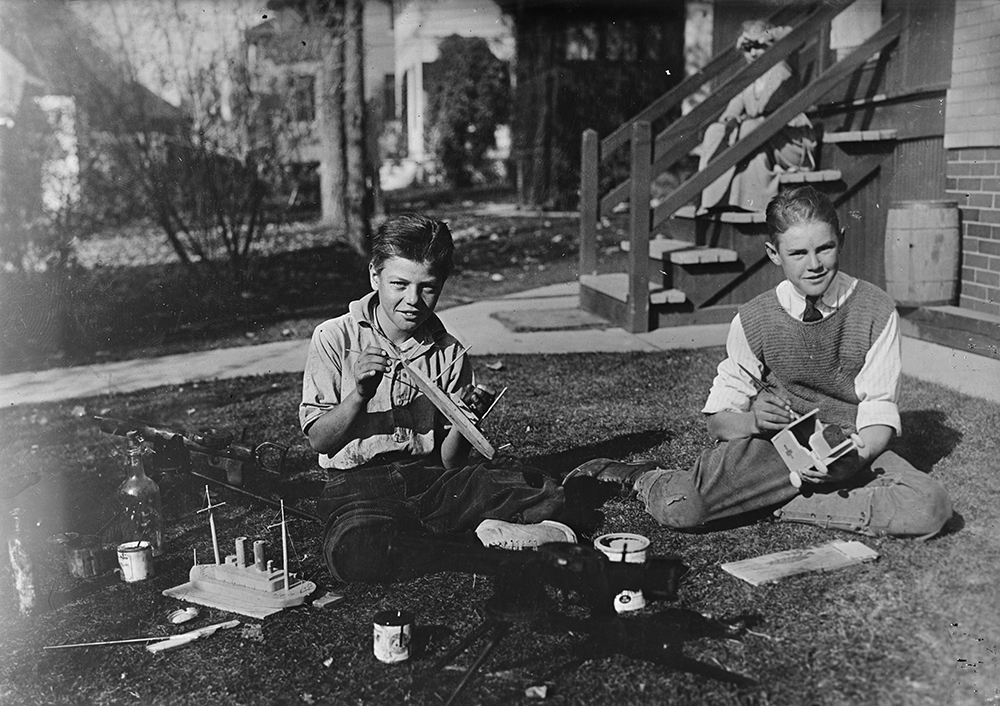

I would argue it’s the same thing. It’s those stories repeated 675,000 times. Fifty percent of those who passed away were between the ages of twenty and forty, which means we were losing parents and schoolteachers, police officers and city council people. These are the leaders of a community.

More than half a million people pass away, which means you’ve got hundreds of thousands of children orphaned; you’ve got families devastated, losing, in some cases, the primary breadwinner or the primary child rearer. This sense of chaos permeates the society as a whole, and it’s happening at the same time that the war is just coming to a close. Another tragedy was that this wasn’t a story that was publicly told, discussed, remembered, or commemorated. So these people suffered through these losses and then were asked to do so in private and quietly for the rest of their lives.

Why do you think that happened? Why do you think the flu pandemic, which existed in these people’s personal memories and had such huge impacts on their lives, didn’t then translate into public memory?

One reason is that the pandemic didn’t transform the society. You had asked earlier if there were major reform efforts at the time, and the reality was that the status quo was really powerfully reinforced during the pandemic. So there was no public transformation that would pull us back to remembering it. You wouldn’t say, “Well, that’s when this thing changed.” It changed things, but it changed things in people’s private lives.

But the other, more obvious answer, and also crucial, is the war. During the war, it was quite difficult for the pandemic to get public attention. In the aftermath this remained true as well. During the war the pandemic remained, if on the front page of newspapers, in much smaller print than the war headlines. It could even appear on back pages while the war took the major headlines. And in the aftermath this certainly remained true. World War I was a story of American glory and success—“We went to Europe, and doggone it if we didn’t win that war!” That’s the kind of story Americans wanted to tell in 1919–20 and in the decades that followed. The war was, for the United States, a celebration of what people understood as American exceptionalism. We really were the best in the world, it seemed.

To remember the pandemic was to acknowledge that we, like others, had suffered terribly, that we were unprepared, that all the developments of modern science still could not completely protect us, and that we really hadn’t lived up to our national promises in terms of responding equitably to the crisis. That wasn’t the story Americans wanted to be telling in the aftermath of the pandemic. The war was a better account of those years, and the pandemic could be easily subsumed under that story, and once it was there it was easily forgotten.

With respect to the pandemic being overshadowed by World War I, we hear a lot about President Woodrow Wilson and how he handled the war, and especially how he handled the peace, but we never hear about what he did during this flu pandemic. Did he do anything?

No, he didn’t. It’s an easy answer and a tragic one at that. He did not at any point speak publicly about the pandemic to the American people, even though it was going to cost more than half a million residents of this country. He chose to be quiet about it. He was desperately concerned that the pandemic would distract people from the American war effort, and so he simply remained silent. He also did other things that actually helped the epidemic along its way. He worried about the nation’s war effort, and so he hesitated to slow the movement of troops, deciding the war, which by late 1918 was nearly won, was more important than the health of the troops. He didn’t prohibit or delay the beginning of the Fourth Liberty Loan Drive, which meant there were massive kickoff parades held nationwide, parades that would lead in many cities to an immediate uptick in infection rates for influenza. He simply refused to acknowledge the seriousness of what was happening to his country or to turn even part of his attention to the pandemic.

What was the media coverage like? I know you said it wasn’t getting as much coverage as the war, but there must have been some coverage of the pandemic.

There absolutely was media coverage. It was quite different from what we’re seeing now, for a couple of reasons. Again, because the nation was at war, the pandemic was constantly competing for attention. It was very hard for it to get banner headlines. Even on the worst days, in some cities experiences of the scourge still might not be the top headline—it might be relegated to a smaller column or even below the fold. The other thing that’s really different is the infrastructure of the media. They had a much slower dissemination of information, and newspapers were the primary source for news. Every community is paying attention to its own circumstances. So in the small-town newspapers you can get a play-by-play of what’s taking place: who exactly is sick, who might have passed away, and an obituary for somebody’s son who lives in another city would be published in that small-town newspaper. There’s actually a great deal of coverage at the small-town local level, but it might not be on the front page.

Did people know that it was happening everywhere?

Yes, absolutely, because they had been getting the story from the eastern cities, where it struck first. It takes a couple of months for the pandemic, which breaks out on the East Coast, to fully infiltrate the country, and so many communities have plenty of time to track what’s happening in other cities and around the world. Even during the summer, when the first wave is striking Europe—though they’re not aware that it’s going to be as deadly as it becomes—there is coverage of what is happening in these other countries. In fact that’s why it’s called the Spanish flu. Spain was a neutral country during World War I, so without military censorship they actually covered the story of the hardships they faced that summer in 1918. So when it erupted later in its second wave, people simply called it the Spanish flu.

Another example of the ways in which World War I seems to overshadow the flu pandemic: I was trying to think of famous novels or memoirs about Spanish flu, and the only ones I could think of were Katherine Anne Porter’s Pale Horse, Pale Rider and Willa Cather’s One of Ours, whereas I could think of so many World War I novels, all of which seem to be more famous than either of those books. Are there examples? Did people write flu novels and memoirs and we just don’t remember them anymore? Or did people not write them?

Both of those are true. There are far fewer novels and autobiographies that engage with the flu pandemic than there are soldier memoirs, let’s say, of World War I or novels set during the war. There simply are not as many that engage the pandemic. There are a few people don’t know about, however, including my personal favorite, William Maxwell’s They Came Like Swallows. He was an editor at The New Yorker and a beautiful writer, and he wrote a semi-autobiographical novel about his family’s experience. I don’t want to offer any spoilers, so I’ll only say it’s a story that invites you into one family’s navigation of the illness, and it does so with a grace and humanity that I think is matched only by Katherine Anne Porter’s piece.

A tougher novel but certainly one that brings home the horror of what took place is a chapter in Thomas Wolfe’s Look Homeward Angel, again a semi-autobiographical novel. The pandemic isn’t the centerpiece of his novel. Instead, in a single chapter, he records the story of a young man—himself—being called home from college because his brother is sick. The chapter recounts the gruesome details of the deathbed and the ways the trauma of the event only exaggerates the other problems the family is facing; in this case it’s the family’s dysfunction, but it brings home the ways in which the pandemic reveals the problems of a society, the problems of a family, the problems in particular kinds of relationships, and it’s very powerful reading.

Do you have a theory for why there aren’t more of these novels or memoirs? Even nurse’s memoirs, which we see a lot of from World War I?

You do actually find nurses recounting their experiences in a lot of places. In nursing school yearbooks, in the articles that are published in their professional journals, nurses recount at great length their experiences, and they’re often quite upbeat. They’re really something to read. And they read not unlike the World War I memoirs of nurses: “We’ve proven ourselves as competent, as capable, as important public citizens.” And so they do write—but you’re right, I can’t think of a published nurse memoir that is known because of its recounting of the pandemic.

Doctors will frequently reference it in their own memoirs and autobiographies, but never with any joy. Victor Vaughan, who was an important leader in American medicine at the time, writes a tragic account of his own experience. He says at first he’s not going to talk about the pandemic, precisely because it had been such a horrific experience, and then late in his memoir he goes back to it in a part where he talks about the things that continue to haunt him. He suggests that there are visuals that hang in his memory, and one of them is seeing the young men in the army camps and being unable to do anything for them. So again you do have people writing about it, but doctors don’t foreground the story because it was professionally, and sometimes personally, such a devastating moment for them, such a challenge to the things they thought their profession was going to be able to do.

Is there anything about the 1918 pandemic that you think people should know right now? Maybe a common misconception or a useful lesson you think hasn’t been getting enough media attention?

If there’s a misconception, it would be that it initiated in Spain. There are several theories, but certainly one of the most persuasive is that it began in Kansas in the spring of 1918.

And then the most important lesson would be the importance and value of public health measures—that we each have a powerful role to play, and that social distancing and quarantining those who are sick can make an enormous difference. And then the last one I would add, and would again emphasize just how important this is, is that we really need to think about protecting the most vulnerable among us, because they failed to do it in 1918, and we can do a better job. We must do a better job.

Is there anything that you would recommend that people do now to help future historians who want to study the COVID-19 pandemic?

I want to quote a colleague, a woman named Lora Vogt. She works at the National WWI Museum and Memorial, and in a recent conversation, when asked a similar question, said, “I would tell people to just write.” And she’s exactly right. Everyone has a story, and every story will be meaningful to us. Whether your family gets sick or stays healthy; whether you live in the country or the city; whether you’re young or old, middle-aged or rich or really desperate for resources, anyone’s story will have value for us. And it doesn’t matter how you write it. Write a short story, write a poem, start a diary, paint a picture, write a song. There will be opportunities for historians to reach out and appreciate those things in the years to come.

There are already some projects getting started and beginning to collect information. In conversation today with Adriana Flores, the archivist at my own University of Puget Sound, she mentioned that she’s exploring ways for us to do a more systematic collecting of people’s experiences and responses. Apparently there are programs like that being initiated at universities and colleges and archives around the country, and indeed around the world. I would urge people to contribute and participate if you can.

I have one last question. Other than your book, do you have any suggestions for reading material for people who want to learn more about the 1918 pandemic?

Yes. Two we’ve already mentioned, Katherine Anne Porter’s Pale Horse, Pale Rider and William Maxwell’s They Came Like Swallows. These are both fictionalized but autobiographical accounts, and they are both beautifully written and so filled with the realities of life and humanity communicated with great elegance.

An excellent recent history is Laura Spinney’s Pale Rider: The Spanish Flu of 1918 and How It Changed the World. And an outstanding book for a more specific case that isn’t the United States is Ida A. Milne’s Stacking the Coffins: Influenza, War and Revolution in Ireland, 1918–19, a recent work that’s just terrific. And finally, if you’re interested in its impact on the military, which I think really warrants our understanding, is Carol Byerly’s fabulous book Fever of War: The Influenza Epidemic in the U.S. Army During World War I.