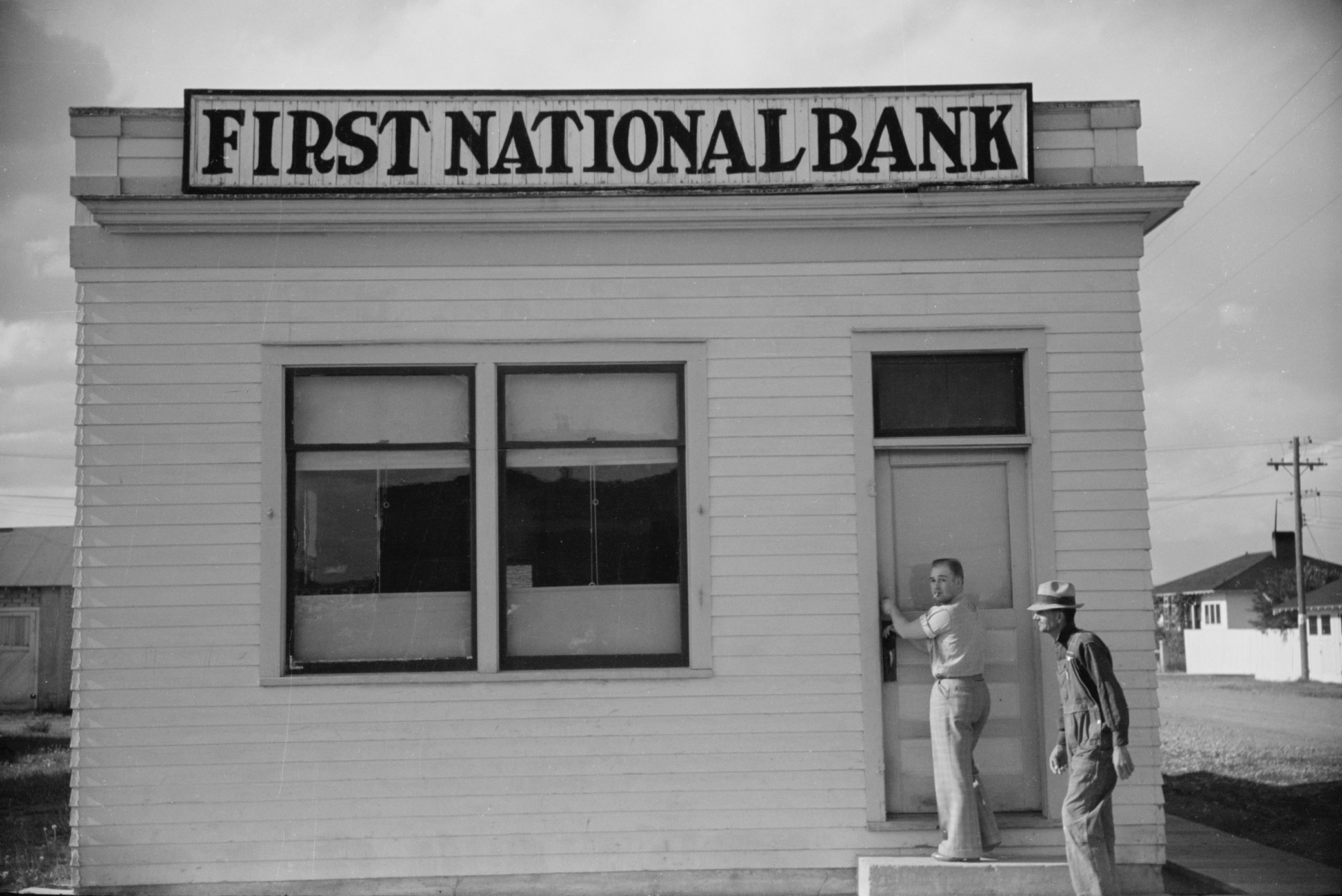

A bank in Fairfield, Montana, 1939. Photograph by Arthur Rothstein. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

As 1932 came to a close, millions of Americans faced a bitter, hungry winter. Unlikely sources betrayed how widespread disaffection with the existing financial system had become. “Are bankers intelligent?” asked an article in the thoroughly respectable North American Review. While at one time conventional opinion could have reflexively dismissed this as the impudent question of an economic radical, recent developments had shaken such assumptions. Alive to the widespread popular outrage, the fiery old Texas Populist James H. “Cyclone” Davis eagerly anticipated a battle he had looked forward to since the 1890s. He claimed that “thousands [of Americans]…now confess that my harangues on the money question were a vision of foresight.” Davis accordingly hoped to see “a row over the Wall Street domination of this country.”

The financial system had wreaked havoc on the lives of ordinary citizens. The self-serving actions of numerous bankers and disastrous state of the nation’s banks forged strong popular demand for sweeping change following the collapse of the private banking system in March 1933. Public anger toward bankers was pervasive and unmistakable. At this moment, President Franklin D. Roosevelt could have remade the nation’s banking system entirely. “Practices of the unscrupulous money changers,” he observed, “stand indicted in the court of public opinion, rejected by the hearts and minds of men.” But rather then embarking on a new epoch in American financial history, Roosevelt elected to save the existing banks. The bankers thus survived this moment of crisis. A strong current of public opinion, however, demanded that the banking fraternity be deposed once and for all.

Events in the nation’s least populous state during the fall of 1932 exemplify the banking fraternity’s public disgrace. Nevada’s foremost banker was George Wingfield Sr., who controlled a chain of banks that dominated economic affairs in the state. As a young man, Wingfield found wealth as a successful gambler and later as a casino owner. The “Boy Gambler” subsequently engaged in lucrative mining ventures in Goldfield that involved the ruthless repression of union miners before relocating to Reno in 1909. Wingfield possessed sizable real estate holdings, had interests in numerous mining concerns, operated the state’s leading hotels, and was rumored to be the silent partner in bootlegging, gambling, and prostitution operations. His economic power accorded Wingfield great influence over Nevada politics, which he exercised as the state’s kingmaker. Nevada’s economic life and existing power structure were severely disrupted on November 1, 1932, when its governor declared a twelve-day bank holiday. The imminent insolvency of the Wingfield chain of banks had forced his hand. Nevada’s economy rested upon mining and ranching, both of which the Depression had crippled. In an attempt to protect his existing investments and sustain the state’s livestock industry, Wingfield had extended and increased loans against doubtful security. His political power meant that state banking officials had turned a blind eye to these practices.

The Wingfield chain was so financially impaired that the bank holiday had to be extended until mid-December. Members of the state’s establishment expressed their enduring support for the beleaguered banker. “George Wingfield is a man of rugged character,” proclaimed the Las Vegas Age, “the one man in a thousand who could come through such a terrible ordeal without any man having the hardihood to charge that he took unfair advantage of any depositor.” But as the extravagant nature of this praise betrays, esteem for Wingfield was far from universal. “Some people,” the Battle Mountain Scout disclosed, “are taking advantage of the present banking moratorium…to belittle George Wingfield’s banking ability.”

“He was damned by many,” reported one contemporary. Another Nevadan later recalled that “there was animosity toward Mr. Wingfield. You could see it on every turn.” Wingfield himself acknowledged that “attacks over the radio have been very bitter.” The Wingfield banks never reopened. While Americans had long considered bankers to be coldhearted and greedy, they were now rapidly concluding that bankers also were inept at best and criminal at worst. “Do you see any of the bankers themselves ruined?” one man angrily demanded. “They’re still riding in their big cars…It takes about as much brains and honesty to run a bank now as it used to take to run a peanut stand.” John H. Puelicher, former president of the American Bankers Association, acknowledged: “I find myself astonished by the general conversation about the incompetence of bankers.” Indeed, bankers were losing any ability to command authority. The Washington State Grange pronounced it was “evident that the private ownership and control of the financial and banking system of the United States has failed.” The Boot and Shoe Workers Union unflinchingly demanded: “What right have bankers in Wall Street got to expect respect for their opinions?” The labor press adamantly pressed the deficiencies of bankers: “Are they wiser than others? No! Are they more farseeing for the public good? No! Are they more honest? No!”

During this crisis, there was no shortage of suggestions for improvement. In November 1932, the American Bankers Association Journal imagined apprehensively, “At this moment, tucked away in pigeonholes and desk drawers, or existing solely as hunches, are hundreds of plans for restoring prosperity tomorrow morning by the simple method of hampering the operation of banks.” Such plans commonly sought to inaugurate a publicly controlled, service-oriented banking system. “Banks should be controlled and operated by states and national government,” proposed a Chicago Defender reader in Detroit who held bankers responsible for “having brought poverty and misery to thrifty American citizens.” A Texan submitted that Congress “should cancel the present banking charters and create national banks, not allowing any individual to own a dollar of bank stock.” And a Norwegian American farmer in Ada County, Idaho, suggested that “interest or usury for private profit should be forever prohibited under penalty of life imprisonment.”

As disapprobation of finance became ubiquitous, businessmen gained new prominence among the bankers’ critics. One Brooklyn wholesaler believed that powerful financial interests wanted to see “small manufacturers and jobbers and middle-class department stores…go by the wayside, leaving a clear road for those in control of money.” Andrew S. Greenfield foresaw this development culminating in a nation of two classes: “The upper with everything in control, and the lower, which will eventually be likened to the slaves in the days of Egypt.” Some businessmen produced radical plans for restructuring banking. The millionaire progenitor of numerous ventures in Nevada and California drafted a blueprint for running the banking system as a public utility. An Ohio manufacturer who had moved to California and become the state’s leading fig producer recommended that the government takeover banking. One small Philadelphia manufacturer declared: “Sooner or later the Government must go into the banking business.”

The era’s most widely recognized representative of American business numbered among the banking critics. Negative public attitudes toward finance help explain why Henry Ford was uncommonly popular for a business leader. “When it is organized as it must be,” Ford submitted, “banks will be the servants of industry…Business will control money instead of money controlling business.” He once claimed that the “difference between me and a capitalist” was that “I earn my living honestly,” unlike the “capitalist [who] loans out his money, collects the interest, and lets the other fellow do the work.” Although Ford made reasoned public appeals for banks to eschew speculation in favor of providing business with credit and depositors with security, his animosity toward bankers was part of a complex personal hatred that included anti-Semitism. During the 1920s, he waged a poisonous campaign against Jews, and he later claimed nefarious Jewish financiers caused both world wars.

Ford illustrates how anxieties about monopolistic financial power could be reconciled with conspiratorial ideas about Jews. This interpretation was most present among businessmen whose faith in the status quo led them to conclude economic problems must be the result of sabotage. In 1933 Representative Louis T. McFadden, who had served as treasurer and president of the Pennsylvania Bankers Association, delivered an ugly speech alleging a global Jewish financial conspiracy. McFadden had completed an abrupt transition from respectable Republican leader to political pariah months earlier, by presenting articles of impeachment against President Herbert Hoover in reaction to his moratorium on Europe’s war debts. McFadden had grown increasingly paranoid in response to the Depression. In 1930 he had claimed a cabal of foreign and New York bankers were conspiring to seize power in the United States. McFadden’s prejudiced outbursts were instrumental to his subsequent electoral defeat. Anti-Semitism occupied a marginal position in banking politics, akin to its unseemly place in American society more broadly.

In the face of widespread demand for reform, bankers spent the Great Depression disclaiming any pressing need for change. As 1931 dawned, Rome C. Stephenson, president of the American Bankers Association, declared the year would witness “the strongest banking situation we have ever enjoyed.” As 1931 closed, Chicago banker Melvin A. Traylor maintained that “the disaster which has overtaken the banking business is not due to the system of banking we have; it is not due to the character and quality of the supervision, nor is it attributable to the management of the banks.” The banking fraternity continued to stubbornly deny the need for reform during the winter of 1932–33. “Is sweeping and radical legislation of a permanent nature called for?” asked Francis H. Sisson, the new president of the American Bankers Association. “I think not.”

Practitioners of banking politics thought otherwise. The United Mine Workers of America noted recent news reports of substantial bank stock dividends: “Millions are hungry while banks pay 14 to 200 percent dividends.” The union warned that “those who are in authority and have the power to change the conditions had better get busy and change them while they still have a chance.” “The day has arrived,” the Reverend Charles E. Coughlin informed his listeners, “when our federal government must establish its own banks throughout the nation for the purpose of safeguarding depositors’ money.” Coughlin thus urged the establishment of “a nationally owned banking system as sound as our army and as honest as our post office.”

As Coughlin’s comment reveals, the Postal Savings System continued to provide a starting point for heterodox banking reform. A few months after Black Tuesday, October 29, 1929, Representative John T. Buckbee (R-IL) introduced a bill to double the postal savings deposit limit to $5,000. While it made no progress, he reintroduced it during the following session of Congress. Such proposals were numerous. Representative Emanuel Celler (D-NY) wrote President Hoover in support of temporarily doubling the deposit limit in order to combat hoarding. Representative Martin L. Sweeney (D-OH) set the bar still higher, a permanent increase to $10,000. The Post Office Department testified in favor of this proposal, while the American Bankers Association predictably opposed any action along these lines. The National Federation of Post Office Clerks reported that bankers “carried on an active fight, deluging members of Congress with telegrams.”

Bankers also combated proposals to have the Postal Savings System offer checking accounts. In 1931 both the Public Ownership League and the Chicago Federation of Labor resolved that in order “to stabilize…the financial basis of the nation,” it was necessary to authorize “the enlargement and extension of the Postal Savings Bank System…[including] the necessary provisions for checking accounts.” The Washington State Federation of Labor declared it would “insist” on checking accounts. Senator Clarence C. Dill (D-WA), who had idolized William Jennings Bryan in his youth, seized political leadership on the issue. Dill was first elected to the Senate in 1922 by a coalition of workers and farmers, and was a noted advocate of public power projects and government radio regulation. In 1932 he introduced legislation to raise the deposit ceiling to $5,000 and permit checking accounts. A number of labor organizations endorsed the measure, including the Central Labor Council of Buffalo, the Montana State Federation of Labor, the Niagara Falls Central Labor Union, and the Central Labor Council of Portland, Oregon. While many working people approved of Dill’s legislation, public discussion of the proper role for postal savings extended beyond checking accounts. “Nationalize the banks,” proposed a retired carpenter and farm laborer. “Then money used formerly to create debts could be used to eliminate them. A year from the establishment of post office banks, all internal debt could be retired.”

The Great Depression left jobless Americans with plenty of free time to consider banking reform programs. Over one-quarter of all union members were unemployed by 1933, including over 70 percent of those in the building trades. The International Molders and Foundry Workers Union of North America urged its members: “Use your public library—it is your friend.” Public libraries played a central role in the daily lives of the unemployed. Libraries in cities across the nation reported that 40 to 100 percent more books were being circulated than before the Depression. One librarian later recalled that in the neighborhood branch in Buffalo where she worked, “you couldn’t keep a book on the shelf.” And these new patrons increasingly used public libraries to pursue financial questions. The New York Public Library reported that large numbers of its patrons were studying economic issues. Carl H. Milam, secretary of the American Library Association, remarked on “the unprecedented demand…for books and other material on economic planning, unemployment insurance, gold standard, business cycles, and suggested methods of recovering prosperity.” According to Scientific American: “The average person now knows more of the mysterious inner workings of economic laws; he is talking it over with the butcher, the baker, the candlestick maker, and they all answer in kind.”

Excerpt reprinted with permission from Money, Power, and the People: The American Struggle to Make Banking Democratic, by Christopher W. Shaw, published by the University of Chicago Press. © 2019 by the University of Chicago Press. All rights reserved.