Monkey Trick, by David Teniers the Younger, c. 1670. Wikimedia Commons, Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp.

Audio brought to you by Curio, a Lapham’s Quarterly partner

A dance of “glorious and strange beauty” took place in a wintry garden in the south of England on January 6, 1614. Funded and planned by the philosopher Francis Bacon, the performance of what came to be called the Masque of Flowers was an elaborate wedding present for two young nobles. But it was also a dramatization of a new habit that had already begun to change the world. On that wintry wedding day in 1614, Francis Bacon’s guest of honor was a gigantic dancing tobacco pipe.

Before the pipe could take the stage, the audience was confronted with its dramatic rival in a battle of the vices: Silenus, the Roman god of wine. The actor playing the deity, described in the masque’s printed stage directions as “an old fat man…mounted upon an artificial ass,” was accompanied by a sergeant at arms carrying a bronze mace engraved with grapes. Given that the performance was part of a lavish wedding during a century when daytime drinking was a nearly universal practice, it’s safe to assume that many members of the audience were devotees of the venerable drunken god at that very moment.

Next came a more youthful and controversial drug, however—one that Bacon’s patron, King James I of England, had bitterly attacked as a source of bad breath, smallpox, traitorous thoughts, and demonic influence just a decade earlier.

Seemingly oblivious to the monarch’s criticisms, the masque’s tobacco-pipe god, Kawasha, appeared onstage (the name was likely a reference to an actual deity of the Algonquian peoples of Virginia that an early English colonist, John White, called “the idol Kiwasa”). His head was topped with a reddish-gold chimney-shaped cap, and his body was garlanded with “tobacco-color stuff cut like tobacco leaves.” He promptly joined in a dance battle with the followers of Silenus, roaring that he would make them “all snuffing, puffing, smoke, and fire.” Kawasha’s attendant pranced around him, holding aloft “a great tobacco pipe” the size of a harquebus rifle.

That’s a pretty big pipe, we can imagine some of the more intoxicated members of the audience thinking.

It was an intentionally over-the-top display, part of Bacon’s somewhat manic lifestyle at the time. Weeks earlier, to celebrate his lucrative new post as attorney general of England, Bacon had treated “the whole university of Cambridge” to a Christmas feast of venison, reported one contemporary.

The 1610s were a key decade in tobacco’s transformation into a new global obsession. Before long, the gift (or curse) of smoking had given rise to one of the world’s most lucrative industries, emerged as a key driver of the Atlantic slave trade, and initiated a global bad habit that humanity still hasn’t kicked more than four hundred years later.

But smoking was about more than just tobacco pipes in the early modern period; the enormous pipe god of Bacon’s dance performance was part of a more complicated, and far stranger, panorama of smoking technologies and practices. The story of smoking in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries is capacious enough to include the distillation apparatus of the alchemist, the water pipe of the cannabis smoker, and even medicinal smoke enemas.

This diversity is not what we would expect from the standard history of smoking, which goes something like this.

Before 1492 smoking was widespread among the tobacco-loving peoples of the Americas but unknown across the Atlantic. Then Christopher Columbus witnessed Taíno men in Cuba puffing on “certain herbs...by which they become benumbed and almost drunk” and, upon further investigation, learned that “they call this tabaco” (this, at least, is what Bartolomé de Las Casas claimed Columbus had recorded in his now-lost journal of his 1492 voyage). By the 1560s a growing number of Spanish authorities began advocating that Europeans take up the practice—particularly the Seville physician Nicolás Monardes, who hailed smoking as a “miraculous” cure for over twenty diseases. And by century’s end tobacco was being grown domestically in areas stretching from Spain to Turkey to Gujarat. Meanwhile, tobacco plantations in the Caribbean and Brazil were emerging as hubs of the Atlantic slave trade. All were in the service of an enormous growth in consumer demand for tobacco that stretched beyond Europe and into Asia and Africa.

The English followed the Spanish example, led by the polymath Thomas Harriot, author of A Brief and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia (1588). Harriott, echoing Monardes’ almost monomaniacal devotion to the drug, praised tobacco for its purported ability to open “all the pores and passages of the body” and cure “many grievous diseases.” Within a few decades, even James I was unable to suppress the drug; his passionate Counterblaste to Tobacco (1604) is remembered as one of history’s most abject drug-policy failures. A decade later, tobacco had become both abundant and cheap throughout Europe, while Harriot lay dying of a painful cancer of the nose that was probably linked to his continued addiction to what James had presciently called a “canker or venime,” or venom.

By the 1650s the tobacco pipe was perhaps the most widespread emblem of globalization and European empire. Smoking had gone global.

Versions of this account of the globalization of smoking have been told countless times. Broadly speaking, they’re true. But they can also be misleading.

Tobacco is indeed native to the Americas, and early modern Europeans, Africans, and Asians did encounter tobacco smoking as a new practice without precedent in ancient texts or preexisting social conventions. But, as archaeologists and anthropologists have been documenting for decades, tobacco was not the only drug that the peoples of the Old World smoked—even before the voyages of Columbus.

While tobacco was becoming a global drug, cannabis was, too—just in a stealthier and far less heralded fashion. Archaeological evidence points to cannabis smoking in Central and South Asia since at least 1000 bc, probably linked to the migrations of proto-Indo-Iranian peoples. One apparent offshoot of this ancient practice attracted the notice of the Greek historian Herodotus, who wrote that Scythian nomads inhaled cannabis smoke inside their woolen tents: “The Scythians then take the seed of this hemp [kannabis] and, crawling in under the mats, throw it on the red-hot stones, where it smolders and sends forth such fumes that no Greek vapor bath could surpass it. The Scythians howl in their joy at the vapor bath.” By circa 800 cannabis use had also crossed the Indian Ocean and become part of daily life in parts of sub-Saharan Africa.

As European slave traders and merchants reached the cannabis-smoking regions of both South Asia and East and west central Africa, the phenomenon of “intoxicating” cannabis again attracted notice. The Portuguese Jewish physician Garcia da Orta, living in 1550s India, admitted that cannabis could be “pleasantly intoxicating” but also saw it as a source of “nausea” and “melancholy.” By the seventeenth centuries, however, some European merchants in the Indian Ocean region had become users of the drug themselves, and at least one brought back samples of the drug to Europe with an eye toward growing the plant locally as a new cash crop, following the model of tobacco.

In 1689 the natural philosopher Robert Hooke gave a firsthand report on the effects of Indian cannabis to the Royal Society of London: “The patient understands not, nor remembers anything that he sees, hears, or does in that ecstasy, but becomes, as it were, a mere natural, being unable to speak a word of sense; yet is he very merry, and laughs, and sings, and speaks words without any coherence.” Hooke described cannabis as being “chewed or swallowed” but specified the dose only ambiguously, as “about as much as may fill a common tobacco-pipe.” It is still not clear to what extent cannabis smoking, as opposed to edible or drinkable preparations, was practiced in Hooke’s time outside of the cannabis-smoking regions of South Asia and Africa.

Hooke also never specified if the anonymous “patient” of his report was, in fact, himself. But he did end his address on a decidedly upbeat note. “Here are diverse of the seeds,” Hooke said, presenting them to the Royal Society at their final weekly meeting before Christmas, “which I intend to try this spring, to see if the plant can be here produced.” If he succeeded in this labor, Hooke believed the drug could prove to be “of considerable use for lunatics.” He concluded: “There is no cause of fear, tho’ possibly there may be of laughter.”

In other words, if Bacon had been after historical truth rather than an impressive wedding present, he might have paid for another personified figure in the Masque of Flowers: a dancing cannabis plant.

An important clue about the multiple pathways for the global triumph of smoking comes from a strange detail of historical etymology.

Whereas the word for “pipe” in virtually every other European language is a cognate of pipe, from the Latin pipa, the Portuguese word for pipe is a striking outlier: cachimbo. It derives from one of the Bantu languages of sub-Saharan Africa, perhaps entering Portuguese via the lingo of slave traders in the Zambezi river valley or Congo during the early seventeenth century. At first glance, this makes some sense. After all, the Portuguese were key players in the Atlantic slave trade, and Brazilian-grown tobacco soaked in molasses (the better to disguise the taste of cheap or stale leaf) was a major item of exchange in seventeenth-century Africa.

Things get more complicated, however, when we dig into the actual meaning of the term that cachimbo seems to derive from: the Kimbundu word kixima, meaning “water well.” This suggests that the Portuguese word for pipe may have originally referred not to the “dry” pipes of tobacco smokers but to a water pipe (also known as a bong). As the geographer Chris S. Duvall noted in his recent book The African Roots of Marijuana, both water pipes and dry pipes were used extensively to smoke cannabis throughout sub-Saharan Africa long before Columbus’ report of a “a certain herb…they call tabaco” reached Europe.

Even the stuff called tobacco was known to contain far more than just powdered leaves in the early modern era. Throughout the seventeenth century, preparations labeled “tobacco” were often a complex mixture of perfumes and drugs, not just a single substance. The contents could range from alternative species of tobacco, such as the more potent Nicotiana rustica, to complex preparations of everything from musk, rosewater, and bergamot to the toxic mineral orpiment. One of the most striking examples of a tobacco mixture comes from the Spanish Jesuit José de Acosta’s 1590 account of a “divine food” (comida divina) prepared by Aztec priests as an offering to the gods. Acosta described it as the ashes of spiders, scorpions, and millipedes mixed with “a great deal of tobacco...and the ground-up seed that they call oluluchqui [morning glory seed], which the Indians drink to see visions.”

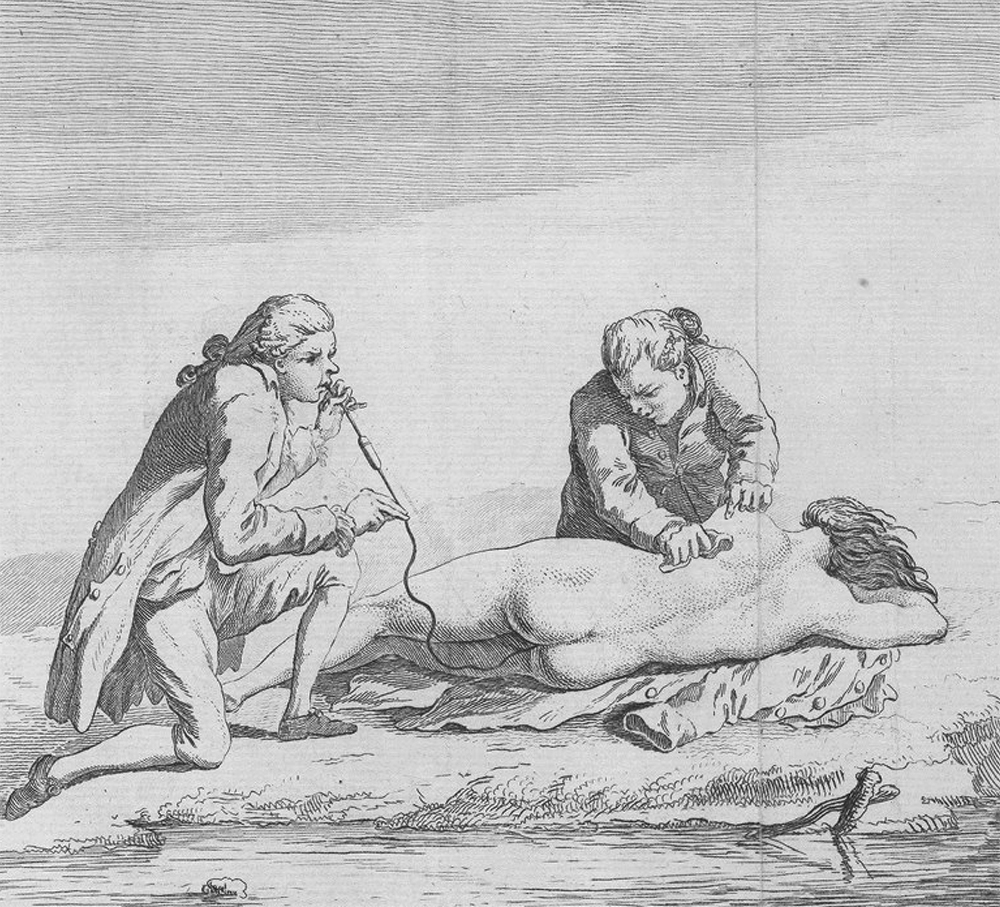

And then there’s the smoke enemas—a practice that early modern Europeans in particular took up with a surprising degree of enthusiasm. The English physician Thomas Sydenham explained in 1753 the general idea in his treatment plan for a fever accompanied by “violent gripings”:

Here, therefore, I conceive it most proper to bleed first in the arm, and an hour or two afterwards to throw up a strong purging glyster [enema]; and I know of none so strong and effectual as the smoke of tobacco, forced up through a large bladder into the bowels by an inverted pipe.

The practice of performing smoke enemas to revive unconscious patients in emergencies was later championed by the prominent eighteenth-century British physician Richard Mead, who wrote that, when trying to resuscitate a drowning victim, “the first step should be to blow up the smoke of tobacco into the intestines.”

By the 1780s, the practice was so widespread that a charitable foundation, the Royal Humane Society, installed a series of emergency tobacco-enema kits along the banks of the River Thames.

As the powers of smoke spread around the world from multiple geographic points of origin, debuting in multiple drugs with an assortment of goals, early modern alchemists took note. They were specifically curious about the potential of fire as a mode of elemental transformation, especially in the human body.

The key concept underlying the powers of smoke was the idea that the human body was porous, shaped not just by the liquids, food, or drugs that we consume but also by the astral forces of stars and planets, the invisible influences of “animal magnetism,” and the airs, vapors, and “humors” of the ambient environment. Medicinal smoke played an essential role in purifying the body of these influences.

Even James I made reference to this commonplace belief in his Counterblaste to Tobacco. Tobacco, he admitted, had a power of “suffumigation” that made it an “antidote” (albeit an “unsavory” one) for the treatment of smallpox. As James put it, it was “a sure aphorism” of physicians “that the brains of all men, being naturally cold and wet, all dry and hot things should be good for them; of which nature this stinking suffumigation is.”

The concept of smoke as a medicinal purging of cold and wet humors within the head—a presumed source of all manner of ailments—soon made its way into a popular series of prints that depicted a young man’s foolish thoughts being quite literally “smoked out.”

Not long before the Covid-19 pandemic, I visited an archaeological lab at the University of California, Santa Cruz, that specialized in fragments of material culture from the Kingdom of Dahomey, in present-day Benin. Among the artifacts were drawers upon drawers of tobacco pipes: tiny shards of clay as white as bone, many still caked with the reddish dust of the earth they’d long been buried in.

Smoking had an enormous range of forms and practices in the early modern period, but by the eighteenth century it had come to center on the disposable style represented by these white clay pipes and the low-quality powdered tobacco they once contained. By the time that cigarettes came to the fore in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, smoking had lost much of the complexity that marked its first phase of globalization. Cannabis smoking persisted, of course, but in an underground capacity, with cannabis tinctures, and not smoke, taking pride of place in medical accounts until recently.

Tobacco smoking has now begun to decline in many countries around the world. Meanwhile, cannabis has been repackaged in an enormous array of different products, from edibles to vape pens. Yet the fundamental human fascination with smoke, that most permanent but most fleeting of companion of humanity, will surely remain.