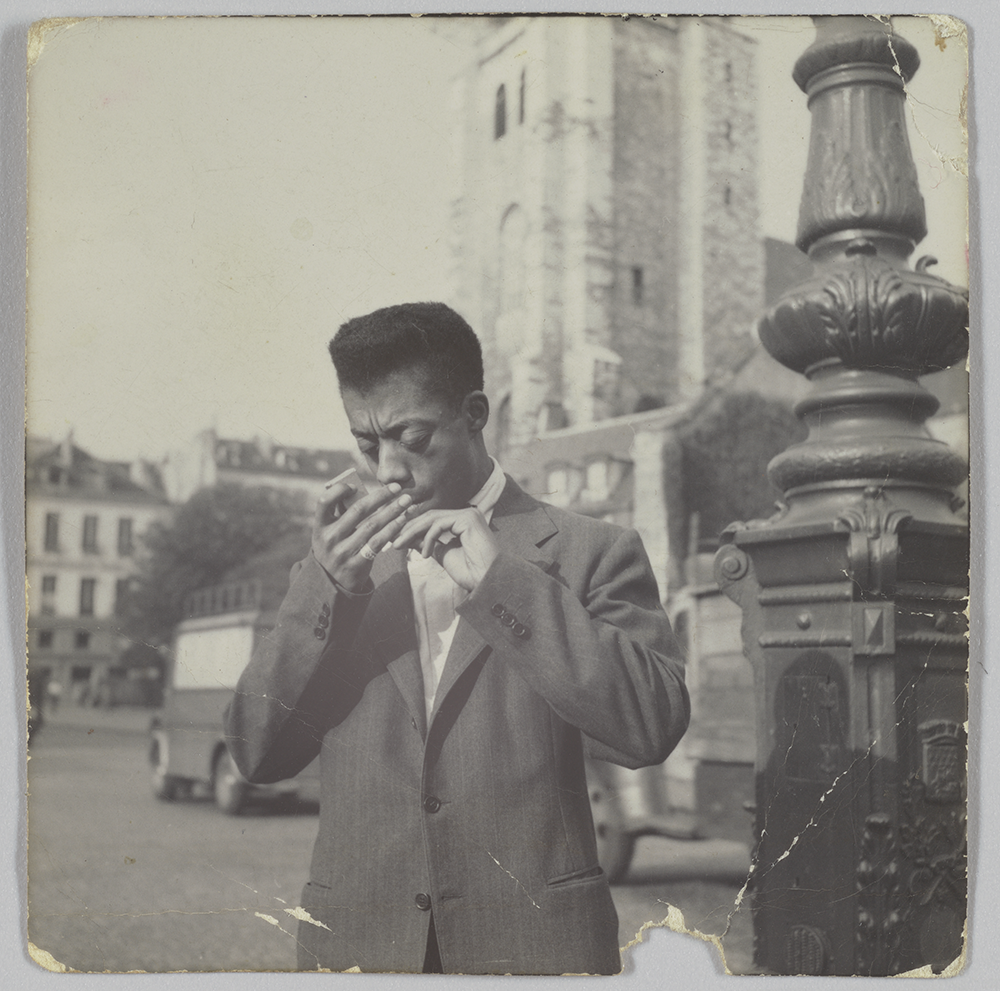

Shortly after arriving in Paris in 1948, James Baldwin met an aspiring novelist named Otto Friedrich, one of many American expats who had flocked to Saint-Germain-des-Prés after the Second World War. Friedrich would go on to become one of the great American editors of the twentieth century. He worked for the Stars and Stripes in Germany and United Press International in Paris and London. In New York, he was editor at the Daily News and Newsweek before moving to the Saturday Evening Post, where he was managing editor from 1965 until the magazine ceased publication in 1969.

At the Saturday Evening Post, Friedrich edited a young contract writer named Lewis H. Lapham. Lapham often paid tribute to Friedrich, who was for him a mentor and role model as well as an editor. “Over the course of a life that didn’t allow him much time to write, he published fourteen books,” Lapham said of Friedrich in a commencement address he delivered at St. John’s College in 2003. “Otto wrote books in the way that other people wander off into forests, chasing his intellectual enthusiasms as if they were obscure butterflies or rare mushrooms—books about roses and Édouard Manet’s Olympia, extended essays about Scarlatti, the Albigensian Crusade, the siege of Monte Cassino and the fires of Auschwitz, books about Berlin in the 1920s and Hollywood in the 1940s, biographies of Glenn Gould and Helmuth von Moltke—a historian in the amateur tradition of Henry Adams, Bernard DeVoto, and Walter Karp.”

In his 1989 collection, The Grave of Alice B. Toklas: And Other Reports from the Past, Friedrich published an essay, titled “Jimmy,” about his youthful friendship with James Baldwin. Nicholas Boggs drew upon that essay for the Paris chapters of his new biography, Baldwin: A Love Story. “He writes wonderfully about Baldwin,” Boggs says of Friedrich on the September 12, 2025, episode of The World in Time. “He writes about their early days in Paris. Friedrich had these wonderful, wonderful anecdotes about the trips they took to the south of France that went totally awry.”

In this excerpt from “Jimmy,” Friedrich quotes at length from the journal he kept of his “expatriate life” in 1949. The Mary who appears in the journal was Mary Keen, “a warmhearted English girl” who “worked for the Communist-run World Federation of Trade Unions by day and then cooked supper for many of the indigent writers in the neighborhood.” An American from Detroit, George Solomos, also makes frequent appearances in the journal under the nom-de-plume he’d adopted, Themistocles Hoetis. Hoetis, née Solomos, was editor of Zero, the little magazine that first published Baldwin’s essay “Everybody’s Protest Novel."

I began to keep a sort of journal of day-to-day events in Saint-Germain-des-Prés, and after all these years, it probably documents the expatriate life in the quarter more accurately than I could describe it from memory. Most of it, of course, deals purely with me, with what I was writing and reading and thinking—I had by now finished two novels, which an agent was trying to sell in New York, and I made a relatively comfortable living translating movie scripts from French into English—but Jimmy and other people keep wandering in and out of my journal, so it is a journal of their lives as well. From any serious point of view, this chronicle is completely trivial, superficial, worthless, and I suppose I should be embarrassed by the record of my own arrogance and ambition. But that is what life in Bohemia is like most of the time. Everyone is young and hopeful and unemployed, and there is a great deal of idle imagining, and just wandering around. Wasted time.

In America, the color of my skin had stood between myself and me; in Europe, that barrier was down. Nothing is more desirable than to be released from an affliction, but nothing is more frightening than to be divested of a crutch. It turned out that the question of who I was was not solved because I had removed myself from the social forces that menaced me.…—James Baldwin, Nobody Knows My Name

August 17, 1949. Met Jimmy at the Royal at 7:30, and along came Lionel [Abel], and Jimmy said, “Here comes my favorite intellectual.” Abel was pleased, and we all went to supper at the Basque place on the Rue Mabillon. It was fairly expensive but very good—Jimmy and I had a faux filet, which was served with Madeira sauce and champignons, and Abel bought a bottle of rosé… One trouble was that Abel and Jimmy had to talk about Richard Wright, a conversation I have heard about a million times. They are still rehashing Jimmy’s article in Zero, with Abel defending the older generation… Abel was very charming, and in one of his explaining moods, so he explained Henry James, Flaubert, Faulkner, Cyril Connolly, Leslie Fiedler, Picasso’s inability to sleep nights, and the absence of an influence of older French writers on younger French writers.

After dinner, Jimmy and I were going to a movie—Back Street with Boyer and Sullavan—but it was way out at the far end of the Rue de Babylone, and by the time we got there, with Abel explaining things all the way, it turned out that the movie had started at nine and not ten, and now it was ten-thirty, so we came all the way back to the Royal, with Abel still explaining (Graham Greene, Sartre, Bernanos, etc., etc.).

We were talking about Milton Klonsky, would-be poet, for whom Abel appropriated Lenin’s term “a gangster of the pen,” and then there he suddenly appeared, trying to be important, so we all ignored him. And then appeared a girl called Nina something, who had just heard Mahler’s Song of the Earth and had just seen a bullfight and had to tell us all about them. And then somebody called Ted rode up on a tandem bicycle, the other half of which was occupied by someone called Siegfried, who had just got back his short stories that very afternoon from Mr. Baldwin, who had told him to tear them up because they were terrible, especially the one about the world-famous pianist who had no little fingers because his manager, Mr. Elbow, had made him cut them off for publicity (and he wasn’t kidding).

August 18. Stephen, the one who wrote that awful novel, was complaining because he couldn’t get his next book written, and he said, “Why don’t you sell me a manuscript?” And I said, “I won’t sell you one, but I’ll write you one,” and Jimmy said, “I’ll write you a manuscript.” Then we said we’d collaborate and write a quick best-seller for Stephen to sell to the movies. Stephen said he was very serious, and we said we were very serious. Stephen said he had already been paid an advance of $1,000, and he hadn’t written a line, and what was he going to do? We said he should give us $400 apiece and we would write 100 pages to justify the advance, and then we would get half the royalties on the finished book. Stephen said, “Dumas did it, so why shouldn’t I?” Why not indeed, we said. So he said we should write a beginning and meet him at the Royal the next night, and we said we would.

After he left, Jimmy and I plotted out the great novel, which was to be called The First Time I Saw Paris, the real and true story of Young Love…We parted, the master and I, solemnly swearing that we would really do it… I wrote six pages this afternoon. Jimmy read them and laughed, and Abel read them and laughed. Jimmy never wrote anything, and Stephen himself never showed up, the bastard.

August 23. Life has an absurd article called “The New Expatriates,” featuring four men with beards sitting in front of the Flore, which is too expensive for anybody under thirty. Wonder who they might be. The article says: “The kids are worried about their work too. Three years, they say, and still no Hemingway.” Wonder where they got nonsense like that. Imagine, not a day complete without somebody saying, “Three years and still no Hemingway.”

August 24. Herb Gold, another one of Mary’s discoveries, introduced me to a withered man called Newman, a professional “promising young writer,” now almost 40, somehow connected with the New School for Social Research. He was denouncing Jimmy, said Jimmy had “never fulfilled himself.” He had a copy of the first Zero, and he said Jimmy’s article was badly written, and I said it wasn’t badly written. He said it’s pretentious, and I said it’s not pretentious. He said it’s immature, and I said it’s not immature, and he said, “You’re being dogmatic.” Somehow this turned into an argument with Gold and his wife about Saul Bellow, now living on the Rue de l’Université, and Edith Gold said Saul Bellow is the most talented writer in America, and they all shook hands. I said Jimmy had more talent than Saul Bellow would ever have, and they all glared at me. Edith said it was “presumptuous” of me to compare someone who had already published two novels with someone who hadn’t published a single one. Newman said to Gold that “some young people” felt they had to denounce people they were afraid of (!!!).

August 27. These arguments can go on and on. Jimmy was very mad at Newman and raged at him about all kinds of past history from Greenwich Village. Newman got very defensive. “Well, I may not know much about literature,” he began one round, and Jimmy said, “Why, you know nothing whatever about literature.” Jimmy bet Newman a dinner that within three years, he, Jimmy, would have a novel published and well reviewed, and that I would too.

September 2. Jimmy got a very sad letter from Themistocles because he has spent months down in Tangiers with the Paul Bowleses, trying to put together the second issue of Zero, and now he says the Moroccan printers have made a mess of it. They have no decent paper, so it’s all done on newsprint, and the printers can’t understand English, and they ignored all the corrections on the page proofs, so it’s all full of mistakes. I still have no idea what’s in it except for the two articles by Jimmy and me (mine on Thomas Mann), but Themistocles is bringing it back with him next week.

Jimmy has found a poem that he likes, and he tacked it to his wall because he says it applies to all these people around here. It’s by Louise Bogan, and the last lines say: “Parochial punks, trimmers, nice people, joiners true-blue. / Get the hell out of the way of the laurel. It is deathless. / And it isn’t for you.”

September 4. Jimmy is still supposed to open as a singer in a nightclub in the Arab Quarter on the 15th. A little hard to imagine.

September 6. Everything is sultry and sticky because it rained very hard last night… Wandering down the Rue des Saints Pères, I ran into Jimmy and Herb Gold having a fierce argument right out in the street next to the post office. Gold had said, “I have a bone to pick with you.” He wanted to know whether Jimmy had really said various things he had been quoted as saying. Jimmy wanted to know what he had been quoted as saying. Had Jimmy really called him “a Sunday school teacher”? Well, yes. Gold said he wanted to know what Jimmy really thought of him. Jimmy said he thought Gold had a lot of pretensions. Then Gold started firing back and said Jimmy was prejudiced and cynical and “maladjusted.”

Jimmy later appeared at the Royal, fuming, but claiming he had won the argument. And then who should appear but old Schaefer, the would-be philosophe, devotee of Gurdjieff and Ouspensky, just back from America and 25 pounds heavier, with a great fat belly under his T-shirt, stuffed with German-American home cooking. He said he had a bottle of Seagram’s, so we all went to the Hôtel de Verneuil to drink it, but first we had to wake people up even though it was only midnight. We went to see Gidske, everybody’s favorite Norwegian journalist, and Jimmy pounded on her door, and she said, “What is it?” and he said, “Open the door,” and she said, “Are you drunk?” and he said, “No, and it’s important.” There were angry mutters from behind the door, and then she opened it, and she and Schaefer fell into each other’s arms. Then we banged on Mary’s door, and she appeared blinking in a bathrobe, and then we spent two hours chattering and drinking up all of Schaefer’s whiskey.

September 8. I was sitting at the Royal with Jimmy and Schaef and Gidske and being monumentally bored because they all talked about nothing but Bicycle Thief, which I had never seen, and then Themistocles appeared in front of us, carrying the new issue of Zero, which we all started reading. It is very nice to see one’s own name in print. Themistocles then started talking for hours about how wonderful North Africa is, and all his fancy new friends, Capote, Vidal, Cecil Beaton—it all sounds like a circus. The plan now is that Jimmy and Gidske and I will all go down there for two weeks at Christmastime.

September 12. I had drinks with Tommy and the talk got around to Jimmy, and he said, “Is this on the record or off?” and I said, “Either,” and he said he was going to “have to let him go,” i.e., Jimmy is sacked, fired, and all his daydreams of security are finished. And he hasn’t gotten much good out of them either. Since he began that job a couple of months ago, he scrapped the second version of the novel and began writing a short story, and he worked on that for a few weeks, and then scrapped it, and then he went back to being a novelist, and this time he said he was concentrating on a completely new novel, the one about Greenwich Village, So Long at the Fair, but what has become of it? He has to stay here until he has made the grade. Each time in his life that he made a great leap, he made it impossible to go back. Once he escaped from Harlem, he couldn’t go back there, and now he can’t go back to Greenwich Village. He came here without a penny, and he’s been living by borrowing ever since. I asked Tommy to try to find him another job before firing him, and he said he would try, but he has been paying Jimmy out of his own pocket because there is no official budget for him to have any filing clerk at all, and he thought the company would agree to it, but he has been turned down. Now what jobs are there in Paris for somebody like Jimmy?

September 13. Tommy asked whether I had told Jimmy, and I said I hadn’t, and he said to say nothing because he “might not have to let him go after all.” He refused to explain.

September 16. Went with Jimmy, Gidske, and others to see La Tour Eiffel Qui Tue, a kind of musical extravaganza about the Eiffel Tower going on a rampage of crime and vice. My favorite song was the one where a girl comes on stage with a baby and starts singing her complaint: “C’est un enfant naturel. Son père est la Tour Eiffel.” Later we met Mary at the Royal and began improvising an American version. The first scene takes place on the ruined plantation where young Marybelle plans to run away to Hollywood while wise old Pappy Baldwin tries to dissuade her: “Don’t go, gal, don’t go.”

September 17. Themistocles and Jimmy went to have lunch with Sartre except that they didn’t get any lunch. Themistocles says Sartre is going to write a piece for Zero, and Jimmy suggested that Sartre republish his piece on the Harlem ghetto in Les Temps Modernes. Sartre was reported to be interested.

September 18. Commentary keeps asking Jimmy to write an article for them, and he was wondering aloud about what he should write, and I told him to write the full-scale article about Richard Wright that he keeps meaning to do, so he said he would do that. Then I began thinking of more ideas and told him to write an article about the character of Joe Christmas in Light in August, which he has been talking about for ages, and he liked that too.

I had thought we were rid of Jacques the actor, Jimmy’s latest love, but he keeps tagging around after Jimmy, even though nobody will talk to him, and he speaks no English. Last night, he got quite drunk and kept saying he wanted to buy a dog. “Je veux un chien, un tout petit chien.” Gidske got very mad at him because he always insists on drinking Pernod while everybody else has beer, and then he never has any money, so somebody else has to loan Jimmy the money to pay for Jacques’ Pernod. It came Gidske’s turn again, and she said she wouldn’t pay unless Jacques drank beer, and he refused. Jacques asked Themistocles whether he had seen Cocteau’s Les Parents Terribles, and Themistocles said he thought it was very bad, and Jacques said that was because Jean Marais was very bad, and that it would have been much better if he, Jacques, had been given the part. Themistocles was speechless. Jimmy has been keeping a journal on the subject, which I read today. It’s about 25 pages and mostly rhetoric.

September 19. Eliott was going to L’Avare at the Comédie-Française, but now his friend has acquired a car and wants to go to Normandy, so I have inherited two good tickets, one of which is supposed to be for Jimmy, which seems sort of silly since he can’t understand what’s happening on the stage. I told Mary I would try to talk Jimmy out of going, but he was adamant about how much he wanted to go.

September 20. My clock was slow, and so I didn’t get to tell Mary that Jimmy insisted on going to L’Avare until 7:00 or so, and then I went to meet Jimmy at the Royal, but he wasn’t there, so I had a quick supper and then went back to the Hôtel de Verneuil to get Mary. I left a taxi waiting outside, only to find out that she was in bed and didn’t want to go—or did, but didn’t want to get dressed. I told her to put on a pair of pants over her pajamas and come on, and she said, could she really? And I said, sure. So she put on a sweater over the pajamas, and then a skirt, and rolled up the pajama legs, and off we went. The play was marvelous, but Mary kept fretting because her pajama legs kept getting unrolled.

September 22. Much confusion last night. I saw Jimmy and Themistocles briefly at the Reine Blanche, and Themistocles said, “This is the night Jimmy is going to blow his stack about everything.” But Schaefer and I were going to play chess, so we went on to the café across from the Métro. Jimmy came by at about midnight to say good night, and then Schaef and I went on playing chess until about one, and then went to the Auberge to have a croque monsieur. Then Gidske appeared at about two, and Schaef went over to the Reine Blanche to see if anybody was still around. He came back saying Jimmy was there with two Cubans, so we went over there. Jimmy tried to pick a fight with me about the book translation that Tommy has been negotiating for us to collaborate on, but I didn’t feel like fighting. Then Jimmy took Schaef down to the far end of the bar, and there was much earnest conversation, and then the place was closing, and we all continued to the Bar du Bac, which never closes. Jimmy took Jacques off to a separate table, and I asked Schaef what the hell was going on, and he said Jimmy was telling Jacques to “get lost and stay lost.” They came back, and Jacques was weeping, with great snuffles, and with great hot tears rolling down his cheeks, and Jimmy was tearful too.

September 24. Jimmy is now working on the two articles I suggested he write for Commentary, and with those and the novel, he is now very determined to get some work done. So I had an inspiration and told him to quit the job at Tommy’s place, and to tell Tommy the very next day that he had to concentrate on his writing. He said he’d like to, but he wanted to get his first check from Commentary before quitting. But he was supposed to be fired last Thursday, except that he didn’t show up for work, and then he was going to be told yesterday, but nothing happened, so I guess it will be Monday, but if I could just get him to quit now, he would never know he was going to be fired.

September 27. Poor Jimmy—Tommy told him yesterday that he was through, and he is trying not to be worried, to keep working on his articles. He is also collecting various materials about himself because Tommy said he might be able to help him get an advance on a novel, which I told him not to count on, for God’s sake, but I’m afraid he does.

October 7. Themistocles as the social lion is getting more and more fantastic. Last night at the Deux Magots, he and Jimmy were ensconced in the company of Max Ernst, Truman Capote, Stephen Spender, Simone de Beauvoir, and God knows who else. Too much for me, so I retreated to the Reine Blanche, where Jimmy and Themistocles later appeared, bringing with them a tall, gaunt fellow called Frank, who kept babbling about having to take Daphne to Chartres the next day. Frank paid for everybody’s drinks, while Themistocles pushed Jimmy’s writing, and Jimmy pushed Jimmy. After Frank left, Themistocles said, “Well, that’s one way to get a book published,” and Jimmy said, “It’s the only way to get a book published.”

But how the hell can he get it written when he spends so much time lobbying for its publication? The Richard Wright article, which was going to be in the mail to Commentary on Monday or Tuesday (it being now Friday) has only gotten as far as a first draft, which he doesn’t like. And the new novel is only on page 19, which doesn’t look very promising, although he still talks about getting it finished by Christmas. I was in his room this afternoon, and read what was in the typewriter, and it sounds just like Crying Holy all over again—has a character called Gabriel who discovers the Lord, and whose mother was a slave. I said, “Is this new novel just a new version of Crying Holy?” He said, “Well, yes and no.”

October 9. At the Reine Blanche again with Jimmy and Frank, who seems to have not only a large expense account but the authority to buy manuscripts for Doubleday. (The Daphne whom he had to take to Chartres turned out to be Daphne du Maurier, a very pleasant lady.) All night long, he kept getting hiccups, because we were all drinking beer, and he says he gets hiccups when he drinks beer. Jimmy’s technique for curing hiccups is that he holds the victim’s ears shut while the victim holds his own nose and downs a full glass of beer. It always works, for a while.

October 14. I asked Tommy about this business of getting Jimmy an advance on a novel (that was the way Jimmy had put it), and Tommy said that wasn’t the plan at all. What he had planned was to approach several people who knew Jimmy’s work and get them to subscribe to a fund to keep him going—in other words, pure charity. I told him I thought it was a bad idea. But he hadn’t done anything about it anyway. Later I saw Themistocles outside the Deux Magots and asked him where Jimmy was, and he said Jimmy was inside with Frank and Capote and him, Themistocles himself. “And don’t interrupt,” Themistocles said, “because they’re finally talking turkey about Jimmy’s novel.”

October 16. A long, tangled evening at the Reine Blanche ending up at the Pergola at about 5:00 a.m.—full of Africans sleeping on benches and women singing in Spanish while somebody strummed a guitar. At one point, one of the Africans got up and led a French girl to a telephone booth, and they both crammed themselves together inside it for five minutes. And nobody paid any attention. I was grumbling to Jimmy about Themistocles’ continual intriguing, and Jimmy said, “I know what Themistocles is doing,” and I said, “I know, he’s trying to sell your novel,” and Jimmy said, “He’s sold it.” He was vague on details, but Frank is going to pay him money every month to get him through the winter while he writes it. But now he says he can’t write it in Paris, so he wants to go to Tangiers in about a week, leaving all his debts behind him. Paris may be distracting, but I can’t imagine him getting much done in Tangiers.

October 19. All of a sudden, two fat characters in raincoats appeared at the door of the Reine Blanche and said this was a raid. For what? For suspicious characters without identity papers. I had all my papers in order, so I had no trouble. Frank had all his papers in order, so he had no trouble. But Jimmy had no papers with him, no French papers, so they said, “Ah-hah, and what do you do?” He said, “I’m a writer.” They said, “Ah-hah, and what do you write?” He said, “Novels, stories, articles.” They said, “Ah-hah, and who do you write for?” He said, “Partisan Review and Commentary and The Nation.” They said, “Qu’est-ce que c’est que ça?” They looked as though they were about to drag him away, but then he had an inspiration and said, “And also for Temps Modernes—for Jean-Paul Sartre.” And then they said, “Ah,” and there was no further trouble.

And whom should they grab but innocent, law-abiding old Schaefer, whose carte d’identité had expired, and who was led off smiling the smile of the unjustly accused. Jimmy was quite frantic and started asking questions like “Do they beat them?” So Frank and I went off to the local police station to see whether anything could be done. The police said they were going to hold Schaefer until they could “vérifier son identité.” How long would that take? Overnight. Frank got very indignant and began blustering about all his friends in the embassy, but this had no effect on the gendarmes. There were about twenty-five of them all sitting around and itching for something to do, and one of them got up and came swaggering over to us, bristling, and said, “Vous manquez de correction,” which is about as ominous a phrase as I’ve ever heard from a French policeman, so I got Frank to calm down and leave. It was noon the next day before Schaefer returned to the Quarter, unshaven and cheerfully smoking his pipe. They had said, “Do you go to the Reine Blanche often?” He said, “Fairly often.” They said, “Do you know its reputation?” He said, “Yes, but I don’t mind.” They said, “Why do you go there?” He said, “To visit with old friends.” So they photographed him and took his fingerprints and turned him loose.

Jimmy is supposed to get his first payment from Frank on Friday. Then he and Gidske and Themistocles leave Paris on Sunday for Tangiers, where Jimmy and Gidske stay until Christmas.

October 23. I had quite a row with Jimmy in the Bar du Bac. I said he never got his writing done, just kept talking about it. I said a writer has to set himself a quota and get that done every day, no matter whether he feels like it or not. Jimmy said I was talking like a hack. I said better a hack writer than a nonwriting talker.

October 26. About midnight at the Gare de Lyon, where they were all leaving. Themistocles, with a homely but very expensive-looking American girl, and Jimmy and Schaef all at the dégustation, having cognac, so I had one too. I asked where Gidske was. They said she was guarding the baggage, because this was really a train to Toulon, not the Riviera, and all full of sailors, and there were two tough characters in the compartment, so they didn’t want to leave the baggage alone. I went out to look for her and found the compartment with the two tough characters eyeing Gidske, who sat peacefully reading an article by Lionel Trilling about The Princess Casamassima in an old copy of Horizon. So finally it came train time, and everybody piled aboard, and there were fond farewells, and the engine began puffing forward, leaving Schaefer and me and the American girl, who, on closer inspection, had green slacks and a red coat and two different kinds of American cigarettes, and lots of money. Themistocles had met her in Hollywood. She paid for the taxi back to St. Germain, and then we filled her full of Pernod, at her expense, and she seemed to get very interested in Schaefer, and he in her, so they left together. Then he came back in about three minutes and complained because she hadn’t invited him into the cab. “You’re supposed to just get into the cab, for God’s sake,” I said, “not wait until you’re invited.” “You’re right,” he said. “I’ve been getting out of practice.”

November 4. Had lunch with Schaefer, who has a long letter from Jimmy. According to some mistake by Themistocles, it turned out when they got to Marseilles that there was no boat sailing for Tangiers on the supposed date of sailing and would be none until a week or so later. It also turned out that a ticket to Tangiers would cost so much that the sum remaining for a month in Tangiers would be so infinitesimal that they decided to give it up and retreat to Aix-en-Provence, where they have entrenched themselves in some small hotel. The theory is that they will stay there a month, at the end of which Jimmy will send off a large chunk of the novel to Frank, who will then send enough money to get to Tangiers. By this time, Gidske also hopes to get some money from Norway.

November 9. Schaefer got a letter from Gidske that says that Jimmy is sick. At first, they thought it was a bite by what Gidske calls “a bedbog,” but then it got worse, and he had to go to the hospital. They said it was an inflamed gland, which had to be opened. Jimmy asked Gidske to ask Frank for the December 1 installment, but I don’t know whether he will pay. He didn’t like the idea of Jimmy’s leaving Paris in the first place. Gidske is also cabling some other friends for money. I went to see Themistocles’ lady friend, the one in the green slacks, and asked whether she still planned to send money to the stranded people. She said no—Themistocles took her last payment and went on to Tangiers—so I gave her a big sob story about Jimmy being sick and got five thousand francs in cash, which was about all she had, plus a promise to send fifty dollars as soon as she got back to New York the following week.

November 14. Gidske writes now that Jimmy is better, but they still don’t know whether he needs another operation. She says they have given up on Tangiers and will stay in Aix, because it’s so cheap, and then return to Paris next month. Her English continues to be miraculous. She describes Jimmy’s hospital as “croded, dirty, unafficient, and smelling like a hors stable?” It is also full of “doctors and nons.”

November 18. I got a letter from Jimmy, confirming that they aren’t going to Tangiers but will be back in Paris at Christmas. And now it’s only the first section of the novel that he hopes to have done by Christmas.

November 19. Another letter from Jimmy, very treacly. “I’m sorry for whatever pain I’ve caused you. I’m thinking particularly of the last ghastly months in Paris, and I hope I never behave in such a fashion toward you again. I always hate myself for it; get terribly frightened that perhaps you don’t want us to be friends any longer, and who in the world could blame you?” What is one supposed to say to that?

November 25. A letter from Gidske, which sounds pretty despairing. Jimmy’s “soar” has “reopened,” whatever that means. They are coming back to Paris as soon as possible and Jimmy is going to the American Hospital for a complete overhaul. They phoned Frank, and he promised to send 15,000 francs, but the hospital bill there is 13,000, and they are holding Jimmy’s passport until it’s paid. Then there is a month’s hotel bill to pay, and the trip back costs 3,000 apiece. The whole Tangiers expedition sounds like one of the more disastrous crusades. There seems to be no way out except bouncing oneself off the consulate, which Jimmy tried in Marseilles, but they refused.

November 29. Gidske sent me a telegram saying Jimmy would be returning alone at 7:30 a.m. today, so I stayed up all night reading Moby Dick and then walked all the way across Paris in the dawn to the Gare de Lyon to bring home the dying gladiator. And what a sadder and wiser man he seemed to be. Kept saying that I had been right “that awful, awful night” at the Bar du Bac—and which of the many awful nights was that? The one in which I said he might never get a novel written at all. He seems much chastened by his terror in Aix, but I can’t help thinking it won’t last. As soon as he collects some new admirers, it will all go back to the way it was.

December 3. Nothing is going on. Jimmy seems to have disappeared completely from sight, having moved to a cheaper hotel on the Rue du Bac and never coming out. I am going to hear Kempff play three Mozart piano concertos and then the opening of La Dame aux Camélias with Edwige Feuillère as the Dame.

December 6. Saw Jimmy briefly for the first time this week. He is holed up in the Grand Hôtel du Bac in the best and cheapest room he’s had in Paris. He is seeing nobody and grinding away at his novel, but so far only twenty pages. It’s essentially the same as Crying Holy. It ends when the hero is sixteen, so there’s no more of the ill-fated attempt to write about the Greenwich Village intelligentsia. And he’s thinking of going back to Aix to stay in the apartment of some Americans they met there.

December 7. Jimmy is talking again about writing an essay on the Jewish protest novel for the third issue of Zero. I urged him not to. He doesn’t really know enough about it. Should work on the novel.

December 10. Jimmy gave me for Christmas a copy of the Henry James Notebooks, inscribed with that marvelous outcry from The Middle Years, which I had originally quoted to him: “Our doubt is our passion and our passion is our task. The rest is the madness of art.”

From The Grave of Alice B. Toklas: And Other Reports from the Past. Copyright ©1989 by Otto Friedrich. Published by Henry Holt, 1989. Reprinted by permission of The Friedrich Agency.