Hexagonal tile ensemble with sphinx, Turkey, c. 1160. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Jack A. Josephson, 1976.

When the London newspaper the Athenian Mercury, edited and published by the author and bookseller John Dunton, first answered questions about romance, bodily functions, and the mysteries of the universe in 1691, it may have created the template for the advice column. But the history of advice stretches back even further into the past. Advice—whether unsolicited, unwarranted, or desperately sought—appears in ancient philosophical treatises, medieval medical manuals, and countless books. Lapham’s Quarterly is exploring advice through the ages and into modern times in a series of readings and essays.

In the early eleventh century, two Sunni Turkish nomads from the Central Asian steppes, Toghril Beg and Chaghri Beg, crossed the Amu Darya in search of fresh pastures. They eventually invaded southwestern Asia and founded the Seljuq empire. Nizam al-Mulk, born Hasan ibn Ali, became adviser to Chaghri and then later to his son, Alp-Arslan, who was governor of the Khorasan region. When Alp-Arslan succeeded to the throne around 1060 Hasan served as chief minister and principal administrator of the whole empire, governing the region between the shores of the Mediterranean and the borders of Afghanistan. Shortly before his death, Alp-Arslan instructed his vizier to secure the throne for his son, Malik-Shah; after Hasan’s strategic campaign, the teenager took over the empire. Alp-Arslan gave Hasan the title Nizam al-Mulk, Kawam al-Din, meaning “regulator of the state, upholder of religion.”

Hasan ibn Ali was born in Tus around 1019. His grandfather belonged to the landowner class and his father worked as a tax collector for the Ghaznavid dynasty, which ruled a sub-state within the Seljuq empire; when his father left for Ghazni because of various bureaucratic failures, he took young Hasan with him. Hasan received a religious education and early administrative training, working as a scribe to the governor of Balkh before leaving his post to work for Chaghri Beg; some sources claim that his reason for quitting was the high taxes taken out of his salary in Balkh, but it’s also possible that Hasan felt it was a strategic move. According to the thirteenth-century historian Ibn Khallikan, Hasan told a story of a Sufi who advised him to “serve Him whose service will be useful to you, and be not taken up with one whom dogs will eat tomorrow.” Shortly after that, Balkh fell to the Seljuq dynasty. (When he came to power Hasan granted many special privileges to the Sufis, supporting them financially and founding hospices for their care, as well as setting up colleges for orthodox religious education.)

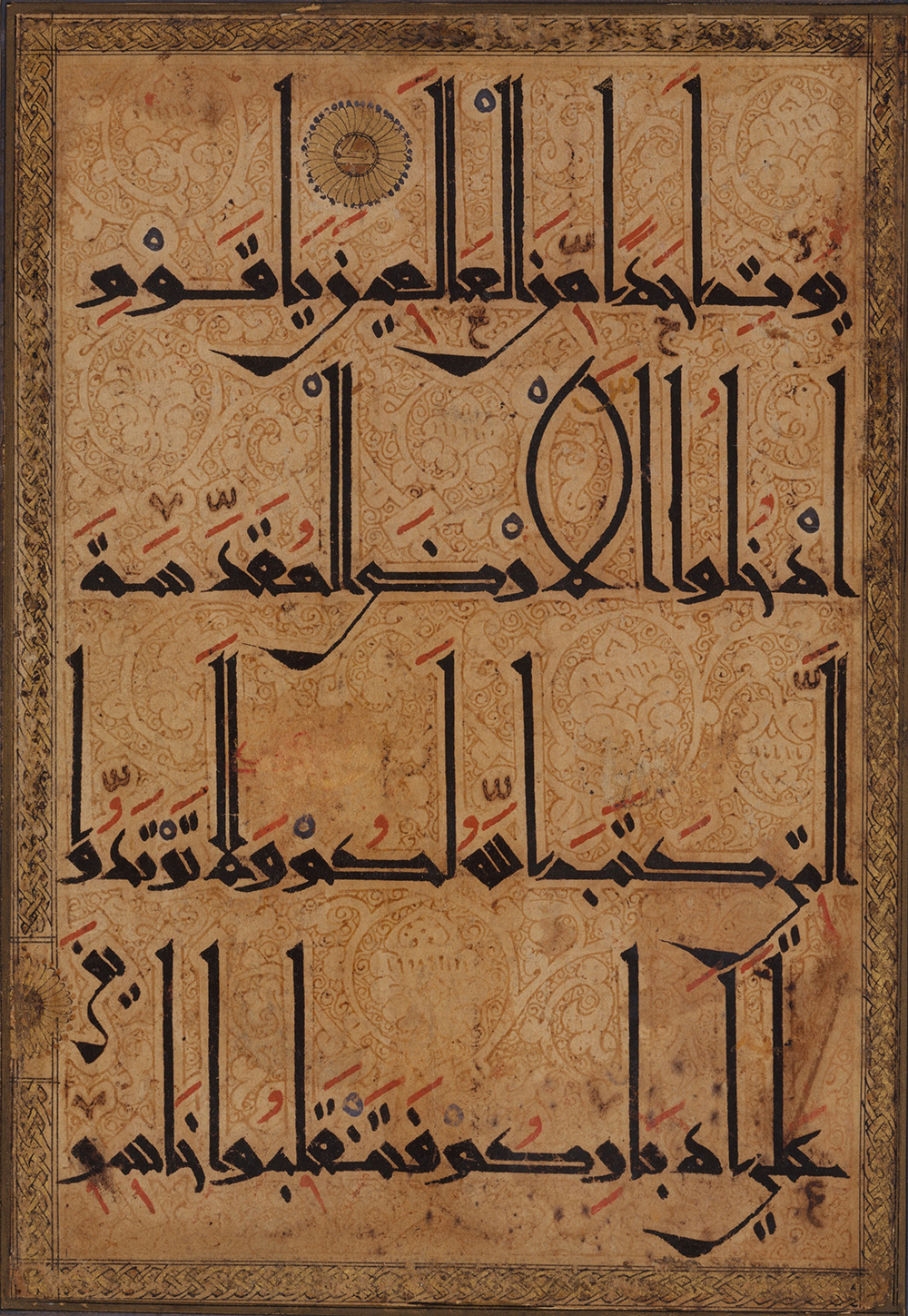

The Seljuq Empire changed the standards for Islamic administrative practices in the Middle East, partly due to the work of Nizam al-Mulk. Around 1086, Malik-Shah asked his four principal officers to produce treatises about administration and governance and the art of kingship. Nizam al-Mulk’s contribution was The Book of Government, or Rules for Kings, which, according to most accounts, was the only submission that Malik-Shah deemed acceptable—and consequently the only one of the four to be published. It set out to determine the factors of political success and the requirements for political stability, taking into account the changing political influence of nomadic conquests across the region on the Persian imperial tradition of government; the author used detailed anecdotes and examples to discuss the importance of an energetic and vigorous state, and present a detailed code of conduct regarding everything from public speaking to the “treatment of the peasantry.” He also dedicated several sections detailing the threats to the empire, especially targeting Shia Muslims.

Towards the end of the century, Nizam al-Mulk became aware of an influential Shia sect of Nizari Ismailis in northern Persia, who were converting alienated subjects on the edge of the empire by preaching a mix of mysticism and Islam. When the Ismailis began infiltrating the kingdom’s castles, Nizam al-Mulk sent troops to kill them; the war ended in a stalemate, but a few months later he was assassinated by an Ismaili disguised as a Sufi monk. Malik-Shah died shortly afterward, and the empire began to decline into various conflicts and power struggles, but The Book of Government, or Rules for Kings remained as a key document on medieval Persian government theory. The text came out of a tradition of advice literature dedicated to rulers, along with other eleventh-century tracts like Yusuf Balasaguni’s Kutadgu Bilig, written for the prince of Kashgar, and Keikavus’ Mirror of Princes, written for the future emperor of the Ziyarid Dynasty (which also eventually fell to the Nizari Ismailis).

Nizam al-Mulk must have felt strongly about the value of such literature; one of his firm beliefs was that effective governance required conferring with many counselors, whom he insisted were “co-equal in the work of ruling.” Shortly before he died he made a speech reminding the sultan that “you have only attained to this power through my statesmanship and judgment,” and that “the stability of that regal cap is bound up with this vizierial inkstand.”

Holding consultations on affairs is a sign of sound judgment, high intelligence, and foresight. Every person has some knowledge, and in every branch of knowledge one knows more and another less. One may have knowledge and never have put it into practice or tested it; another possesses the knowledge and has also used it and tried it. For example, one may have read in medical books the cure of a certain pain or sickness and know by heart the names of all the specific medicines, but no more, while another knows all the medicines and has used them in the treatment of that condition and tried them many times. Never will the first be on a level with the second. Likewise a man who has traveled widely and seen the world and experienced heat and cold and been in the midst of affairs is not to be compared with one who has never made journeys, seen countries, participated in events, or only to a limited extent. Thus it has been said that one ought to take counsel with the wise, the old, and the experienced. Further, some people have sharper wits and quicker perception of affairs; others have duller intellects. The wise have said, “The counsel of one man is like the strength of one man, the counsel of two persons is as the strength of two, and the counsel of ten is as the strength of ten.” Of course, ten men are physically stronger than one; likewise ten men in counsel are stronger than two or three or five.

Everybody in the world agrees that there has never been any mortal wiser than the Prophet (upon him be prayers and greeting); and with all the wisdom that he had—in spite of all this perfection, in spite of all his miracles, God (be He exalted) said to him, “Consult them in affairs.” (“O Muhammad, when you are going to do any work or when you are confronted with an important matter, confer with your companions.”) Since God commanded him to seek advice—and even he needed counsel—it is obvious that nobody can do without it.

Thus when the king does any work or is confronted with urgent business, it is his duty to take counsel with wise elders, loyal supporters and ministers of state. Each person will say what comes to his mind and the king’s opinions will be compared with what everyone else says. When they all hear one another’s words and opinions and discuss them, the right course will stand out clearly, and the right course is that which all intellects agree to be imperative.

A man who does not take counsel in affairs shows weak judgment; a man of this kind is called self-willed. No task can be accomplished without men of the proper skill; no more can any enterprise succeed without deliberation. Praise be to Allah that the Master of the World (may Allah perpetuate his reign) is endowed with sound judgment and served by men of prudence as well as skill.

Read the other entries in this series: Inez Milholland and Eugen Boissevain, George Washington, Plutarch, Lewis Carroll, Chrétien de Troyes, Yan Zhitui, Saadi, Giovanni Della Casa, Maria Edgeworth, Dan McQuade on basketball manuals, and Leopold Froehlich on syndicated advice columnists.