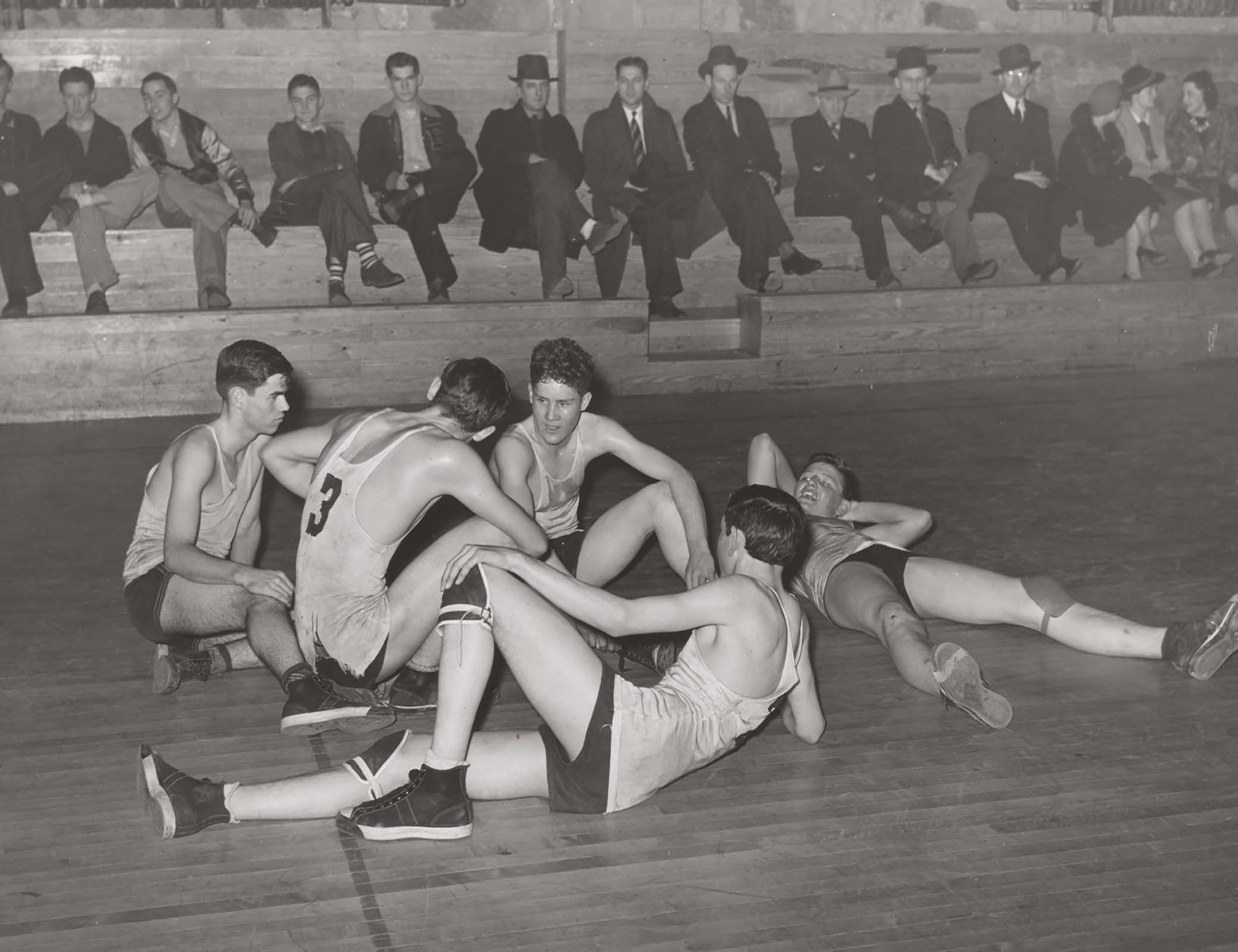

Basketball players resting between periods, Eufaula, Oklahoma, 1940. Photograph by Russell Lee. The New York Public Library, Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs.

When the London newspaper the Athenian Mercury, edited and published by the author and bookseller John Dunton, first answered questions about romance, bodily functions, and the mysteries of the universe in 1691, it may have created the template for the advice column. But the history of advice stretches back even further into the past. Advice—whether unsolicited, unwarranted, or desperately sought—appears in ancient philosophical treatises, medieval medical manuals, and countless books. Lapham’s Quarterly is exploring advice through the ages and into modern times in a series of readings and essays.

Clair Bee was a great college basketball coach. His winning percentage still ranks among the best of all time, more than seventy years after his retirement. He led the Long Island University Blackbirds to two championships at the National Invitation Tournament in an era where the NIT was more prestigious than the NCAA tourney and wrote the foreword to the only book by James Naismith, the inventor of basketball.

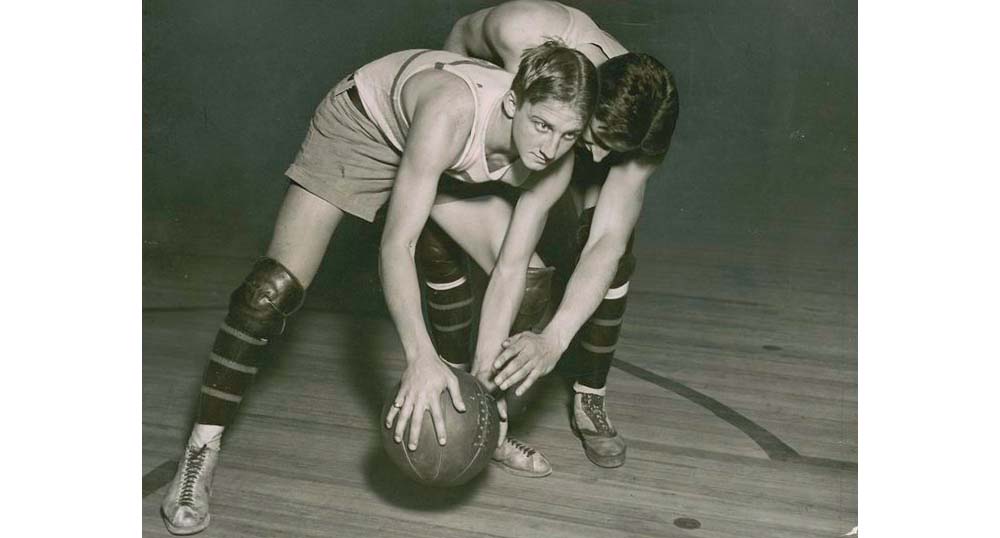

He was a legendary strategist of hoops. Bobby Knight credited him as a mentor and close friend, and many of the sport’s less-notable fans reached for a similar relationship by purchasing the books that professed to offer access to his genius. In 1942, a year after his final championship with the Blackbirds, the A.S. Barnes Dollar Sports Library published four titles on basketball strategy written by Bee: The Science of Coaching, Drills and Fundamentals, Man-to-Man Defense and Attack, and Zone Defense and Attack.

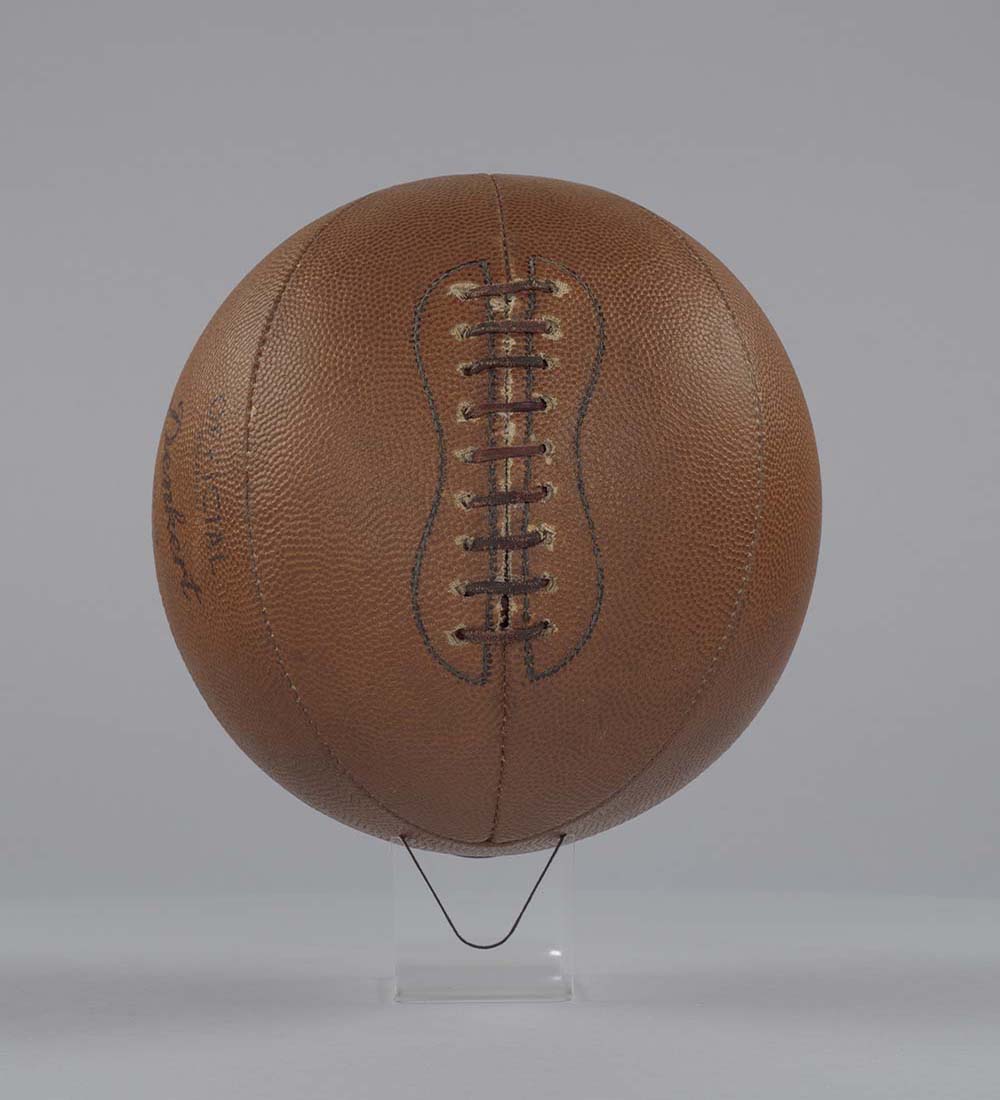

Bee was an appropriate choice to write that last one. He invented the 1-3-1 zone, an aggressive defense in which three defenders are positioned across the court, allowing teams to trap players and cut off their passes. I cover college basketball, and when I bought Bee’s Zone Defense and Attack at a used bookstore earlier this year, I figured it would be interesting to read about old-timey basketball. Also, it was just $1. Despite inflation of 1,761 percent, I could still pay the original price.

The zone defense did not come easily to Bee. The New York Times’ Arthur Daley noted the coach’s preference for man-to-man coverage in 1937, writing that Bee “would like to have all teams using zone defense cooked in boiling oil over a slow fire.” But after his YMCA team lost a game to a team using a zone defense in the early 1910s, Bee began experimenting with it. His 1-3-1 scheme is still used by basketball teams today. “A good zone will give most teams and coaches a ‘headache,’” Bee wrote in his 1942 book on the subject.

But there was another reason I bought a first-edition copy of Zone Defense and Attack: the unhinged essay by sportswriter John R. Tunis that appears on its back cover.

Sport Must Prove Itself!

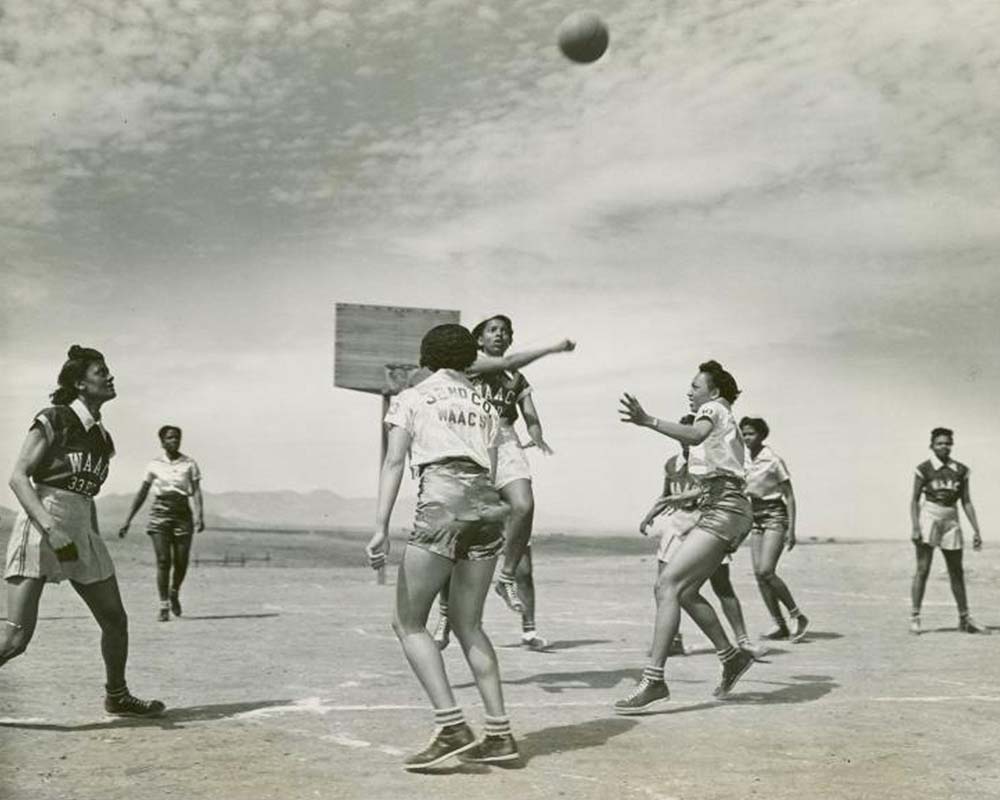

You probably remember that old wheeze about the battle of Waterloo being won on the playing fields of Eton. It’s taken a long while for that one to die out. Those of us who saw Jewish cloak-and-suit workers from New York’s Lower East Side go out under shellfire to repair broken wire on the hillsides of the Argonne in the last war know this was the bunk. That playing-fields-of-Eton gag received a setback in World War I when men who never played games of any sort held off an embattled world in arms over four years. It has received another from the Germans and the Japs in World War II. There weren’t any All-American ends in the German panzer divisions in France and Belgium. There weren’t any draft-shy home-run kings in the Jap spearheads through the Malay States. There were just well-trained athletes, coordinated physically and mentally for the stinking business which is war. These are the men we have to beat. These are the opponents that the products of American sport must master. If they aren’t mastered, American sport will die. So will the American nation.

Today our sport must prove itself. The American heritage in sport must show that free men are not merely the best champions, the best record holders, the best men in the newspaper headlines, but the best men in endurance and combat, in sacrifice and guts, on ship and on shore. Most of all, we must prove that our athletes are not merely tougher and stronger than their adversaries; but because of our heritage of games we are keener, more intelligent, with more initiative and resource than the Japanazi hordes. Of course that means everyone, not just the men on the fighting lines. It means you and me, every one of us, those who love games and sports, those who follow games and sports, those who teach games and sports, and especially those who play games and sports. We’ve got to prove that a games-playing nation is a keen nation, a fit nation, a free nation. We’ve got to make that old playing-fields-of-Eton gag come true.

This is not an accurate preview of what is inside Zone Defense and Attack. Bee writes about how to set up various zone defenses, then diagrams plays that can beat each defense. It is exclusively an instructional basketball manual. Other World War II–era books from the Dollar Sports Library—which dropped “Dollar” from its title when prices went up to $2 in the 1940s—feature only ads for the rest of the series on their back covers. Even the 1945 guide to rifle marksmanship avoids including political commentary in its promotional copy. I could find no other book in the series that printed sports-themed war propaganda.

A.S. Barnes may have approached John Tunis to help sell Zone Defense and Attack because he was an established freelance sports journalist. He had a long career, writing a weekly sports column in the New Yorker as well as being part of the first radio broadcast of a European tennis tournament to the United States. By the time this essay appeared on the back of Zone Defense, he had also written a successful series of sports books for children. Tunis and Bee appear to have no personal connection that would explain the manifesto hiding on this book of straightforward sports advice. But six years after publishing Zone Defense and Attack, Bee joined Tunis in becoming a children’s book author, a career path that saw them both attempting to prove that a game-playing nation is a stronger, keener nation—yet in increasingly divergent ways.

Bee’s twenty-four novels, one published posthumously, follow the clean-cut All-American athlete Chip Hilton from high school to college. As a coach, Bee sometimes stretched the boundaries of fair play to win. While coaching basketball at Rider University, he’d shorten or lengthen the team’s home court depending on which way would stifle opponents. Chip Hilton won a lot, too, but never had to resort to such tactics. He was an ideal sportsman who played fair and hard. When Chip lost, it was usually a fluke: In 1950’s Hoop Crazy, Chip’s basketball team loses on a play where the ball deflates in mid-air and hangs over the rim, allowing a player from the rival team to tap in a buzzer beater. Readers loved these books. When Sports Illustrated’s Jack McCallum, who read the Hilton books as a child, profiled Bee in 1980, the magazine received 130 letters from people who similarly devoured Chip Hilton stories.

The Hilton books were engaging enough to be adored by young readers. But they were also bland. There is little dramatic tension in a series where the protagonist nearly always wins. When Chip is injured—such as the time his leg is broken in a car accident in 1948’s Championship Ball—he becomes team manager and is so instrumental to his basketball team’s state championship that he gets the game ball despite not playing a minute all year. The books occasionally touch on bigger issues: Hoop Crazy deals with a town’s opposition to a Black player joining a team. But sport drives the action, and Chip is always a saint.

Tunis’ books, by contrast, featured main characters with rougher edges. “These are not just children’s action-and-adventure morality plays of the good guys coming from behind to win at the tape or in the final minute,” one Los Angeles Times critic wrote in 1991. “The good guys have faults. The bad guys have virtues. Characters change as situations change and they learn, as do the readers, the lessons of humanity.” Take Tunis’ 1938 novel, Iron Duke, his first book for young readers. The story follows Jimmy Wellington, an Iowa boy who has trouble adjusting to life at Harvard and eventually finds himself on the track team. I found this description of a two-mile race in the novel particularly well done:

Afterward he couldn’t remember much about that race except pain. Pain and the cinders from the men ahead which cut into his legs as he ran. It was nine minutes of steady pain, for the pace was fast. Inexperienced as he was, he knew that. Somewhere about the fourth or fifth lap by desperate running he managed to get up behind Whitney. Then he recalled noticing Whitney after a while fading away. Yes, actually dropping off until only that cursed blue figure remained ahead. Aching legs, tortured lungs, and an everlasting wrangle with that blue jersey on a curve. Arms up, elbows, elbows.

The ball would not deflate on a game-winning shot in John Tunis’ world. Yet many of Tunis’ protagonists were ideal sportsmen that resembled Chip. The main character in All-American (1942), Ronald Perry, deals with his guilt over his classmates’ anti-Semitism. The Duke Decides, published in 1939, examines the growing Nazi party. The Kid Comes Back (1946) has Roy Tucker, a Dodgers player who mentors the rookie trying to replace him. “What helps you helps all,” he tells the new player.

Bee and Tunis differed in tone and plots. But they both thought sport could be a benefit for society—and they hoped their books could teach kids to be good sportsmen like Chip. Yet they also knew that, in an age of increased profits and media attention, winning games was often more seductive than improving one’s character.

In 1950 the City College of New York won both the NCAA championship and the National Invitation Tournament. A state investigation later revealed that bookies had been paying players to rig games. Usually this was accomplished through “point-shaving,” where teams would sandbag, or deliberately underperform, in games to keep the score close, allowing bookies to manipulate point spreads. The college basketball game-fixing scandal is remembered best for CCNY’s fall. But it also ended Bee’s coaching career at Long Island University. Sportswriters told Bee privately that his players were rigging games; Bee still defended them publicly on multiple occasions. In the end more players from Bee’s Long Island University team were implicated than from any other school. The school dropped basketball immediately after the 1951 season and didn’t allow the game to return until 1965.

Histories of the point-shaving scandal usually paint Bee as a hypocrite for writing novels about clean-cut Chip Hilton while his own team fixed games for gamblers. In his 2013 book Hoop Crazy: The Lives of Clair Bee and Chip Hilton, the sportswriter Dennis Gildea writes convincingly that the scandal really did change Bee. His books post-1951 were different. Early books in the series have Hilton yearning for a scholarship to State. After the scandal forced Bee out of LIU, Hilton turns down scholarships and professional contracts in the novels, feeling that such rewards for playing cheapens basketball. Bee still believed in the power of sports but had decided that the professionalization of even the college ranks had become a net negative.

Chip’s no-scholarship stance was corny. But Bee was trying, Gildea writes: “Rather than being the blatantly phony and hypocritical words of a cynical college coach manipulating the system and his readers, as some critics contend, the majority of the Hilton books represent Bee’s efforts to address and reform the wrongs that he saw in college sports and American culture.” Bee’s books presented a man kids could try to emulate in Chip. Gildea quotes Bee’s daughter saying that her father considered the Hilton series the crowning achievement of his life. Perhaps Bee still felt optimistic that basketball’s failings could be redressed—a kind of equanimity that escaped Tunis.

In 1974, sportswriter Jerome Holtzman published No Cheering in the Press Box, a collection of baseball journalism from various well-known authors. Tunis’ contribution to the volume indicts sports in many ways you’ve no doubt heard before: Kids’ sports are too competitive; it’s a shame athletes make more than teachers; everything is overhyped by media people who keep their mouths shut to maintain access. And, he adds, “most sportswriters are dopes.” Tunis had a well-established reputation as a curmudgeon: in his 2001 book King Football: Sport and Spectacle in the Golden Age of Radio and Newsreels, Movies and Magazines, the Weekly and the Daily Press, academic and former NFL lineman Michael Oriard calls Tunis “the Great Scold of college football.”

Yet in No Cheering Tunis can’t stop attempting to prove his worth to readers, perhaps subjecting himself to the same pressure he applied to sports and the country writ large. He exhaustively details connections he’s made over the years, a rhetorical move familiar to those who consume sports media. He notes that John F. Kennedy read his books, Joe Kennedy was a “personal friend,” and Franklin D. Roosevelt said Tunis made him “horse laugh.” Oh, and his mother was FDR’s landlord when he was in college. Some of Tunis’ writing reads like Magic Johnson tweets:

About a year ago I saw Teddy Kennedy, the youngest. This was at a woman’s house near here, at a rally. I was introduced to him and I said, “I roomed across the hall from your father at Harvard.” And he said, “Oh, did you?” And I said, “Yes.” That's all there was to it.

Tunis also revels in the tinier victories of networking within his industry. His 1964 memoir, A Measure of Independence, contains a story where legendary New York sportswriter William O. McGeehan says he threw out a potential essay of his about the myth of sportsmanship after reading Tunis’ superior story. (The book jacket for his memoir obviously featured praise from a U.S. Senator.)

In that essay about the myth of sportsmanship, “The Great Sports Myth,” published in Harper’s in 1928, Tunis suggests that games should not be played for the sake of winning: “Excessive participation in competitive sport tends to destroy character. Under the terrific stress of striving for victory, victory, victory, unpleasant traits of all sorts are brought out.” Tunis may have already decided on an opinion that seemed to run through a lot of his work: The professionalization of sports had turned potential athletes into mere spectators. This problem had seeped down to the lowest levels and ages. In A Measure of Independence, he writes that, in covering the perils of competition, it’s best to show not tell:

Your story must be told simply, quickly, effectively. When you allow a “message” to take over, you are lost. Your audience only wants a story; what happened. But if you tell your story, and in it show what basketball in American high schools has become, what has been done to the game your reader loved since he was able to toss that ball into the hoop above the garage door, he will listen. Explain through the story what sport does to older people in town, how they put pressure on the authorities in school for tickets, how the school people put pressure upon the coach, who in turn pressures the boys. Show how the game warps the thinking of a coach who must win to keep his job, or a high school principal with a family who cannot get seats for the important businessmen in town. Show how this has corrupted our values, how the necessity for victory at any cost has corrupted us: men, women, boys, players, coaches, and spectators alike.

In this light, Tunis’ desire to critique and moralize sports was greater than Bee’s—which is perhaps why Tunis used Zone Defense and Attack as a platform for his strange (and somewhat racist) wartime call to action for American athletes. But the country could never live up to his expectations, and at some point, Tunis stopped trying to get American sports to change.

Holtzman introduced Tunis’ essay in No Cheering this way: “The heroes in the vast Tunis library are not the winners, but the losers. Mr. Tunis has been repeatedly emphasizing that the outcome of a football game, or a track meet, is of only secondary and brief significance. Sports are and should be fun, he insists, but nothing more. Only a fool swallows the guff that football coaches mold character or that the Battle of Waterloo was won on the playing fields of Eton.” Holtzman’s reading of the Tunis canon has the writer spending his career answering the challenge on the back of Zone Defense and Attack, and the answer is an emphatic no. Sports did not prove itself—and neither did John R. Tunis.

Tunis’ essay in No Cheering saves most of its barbs for himself: “I’ve written what I wanted to and tried to explain there is more to life than throwing a football around. You can say that my books have been read, but only by kids, really. Nobody has paid attention. They read, but they don't know what’s in it. Still, my books are important to me. They’re the most important thing I did. Damn right. There was a time when I expected to do some good. But that was a long while ago.”

Maybe the essay on the back of Bee’s book showed that in 1942 he still had some hope that sport could “prove itself” in the service of American exceptionalism—or maybe he was just looking for a paycheck. He writes in his memoir that fewer magazines existed by 1940, and those that did were paying him the same rates they’d paid him decades earlier. His essays for Collier’s in the early 1940s earned him the same $400 they did in 1925. Money was tight. War was raging. He could have just been doing a little copywriting he didn’t really believe. Clair Bee spends more than one hundred pages detailing the strengths and weaknesses of zone defenses. John R. Tunis says playing and watching sports can prove the United States is a free nation. Who gave better advice?

A 1959 second edition of Zone Defense and Attack, co-authored by Ken Norton, had a more traditional back cover, one advertising other books in the series. I have less to say about that one.

Read the other entries in this series: Inez Milholland and Eugen Boissevain, George Washington, Plutarch, Lewis Carroll, Chrétien de Troyes, Yan Zhitui, Nizam al-Mulk, Saadi, Giovanni Della Casa, Maria Edgeworth, and Leopold Froehlich on syndicated advice columnists.