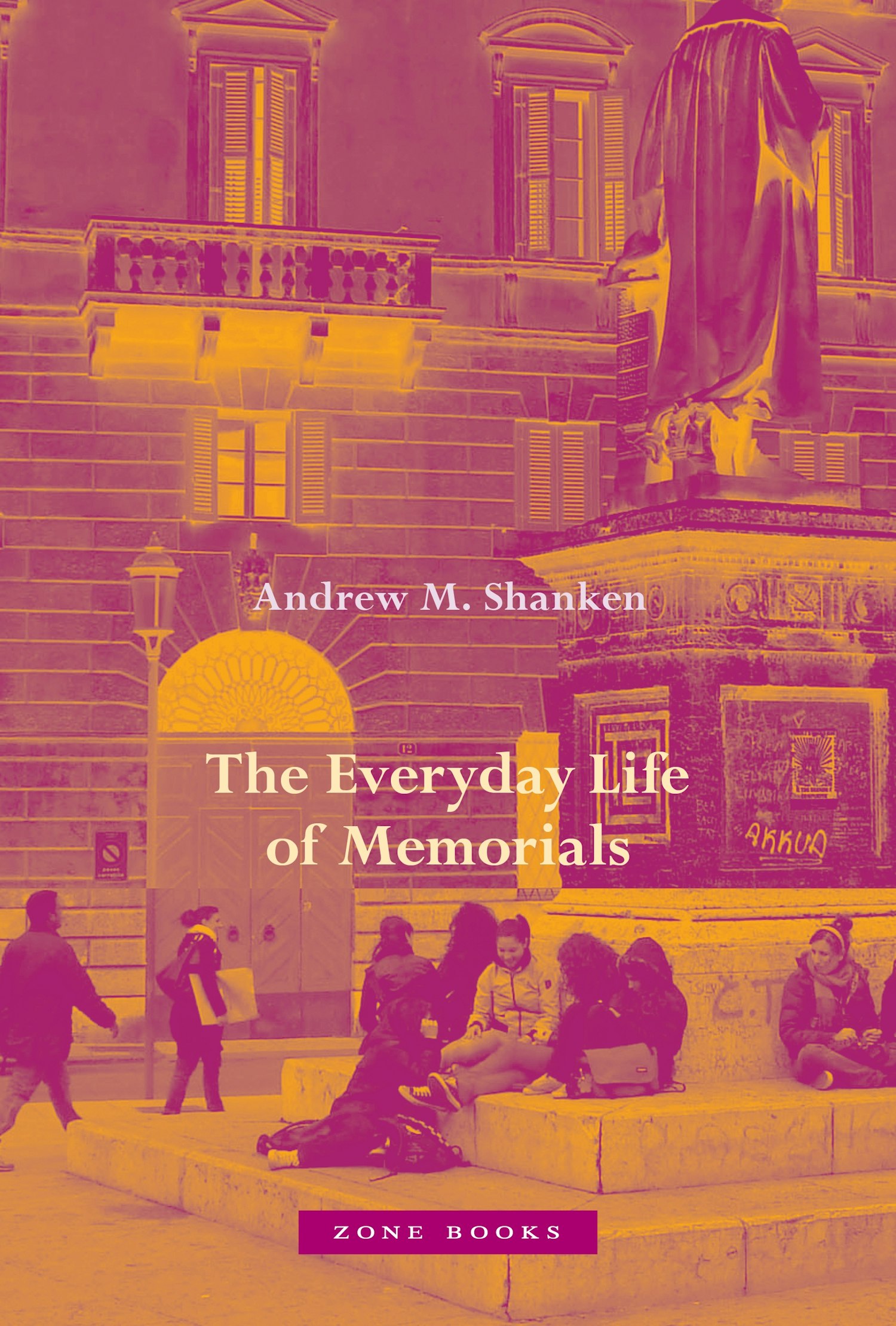

Royal Fusiliers War Memorial, 2011. Photograph by Robert Scarth. Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 2.0).

In 1947 Lord Chatfield, who was admiral of the fleet and president of the War Memorials Advisory Council in England, argued that “though to us the two wars are twenty-five years apart, time will close the gap until they are looked back on as one great struggle against evil.” In commemorative practice, if not in consciousness, wars have run together. The congestion of wars has made assemblage practical, whether as groupings of memorials or by means of additive plaques. Perhaps this is the most appropriate way to acknowledge more than a century of continuous warfare.

If only such madness lay behind the method. The improvised reality comes out painfully in the memorial to the Royal Fusiliers. Instead of erecting a second memorial to the Royal Fusiliers who died in World War II, Londoners carved an additional tribute into the World War I memorial on the Strand in London. To avoid the same problem recurring in the future, they cut out some stone and added a dedication to “those fusiliers killed in subsequent campaigns.” No one will ever have to propose or reject another Royal Fusiliers memorial again.

Such additive plaques or inscriptions rarely mean anything as works of art, but as examples of the place of memorials they become wonderfully expressive. They make sense of the rapid succession of wars, which are treated like one phenomenon, as Lord Chatfield presciently anticipated. The plaques speak to an understandable memorial exhaustion after World War II, while they gesture to continuity. Even the naming of the wars is additive. The generic “World War II” lent its name retrospectively to the Great War whose business it finished. It is no wonder that conventions of memorialization followed. The generation that had fought World War I, that memorialized it, and that then led the charge into World War II had little energy left for fresh memorials. Many war memorials from the Great War had scarcely been finished when the Second World War began. That same generation then immediately entered the Cold War, again a continuation in many ways of World War II, but fought out through proxy wars in Korea, Vietnam, and elsewhere. The dead from all of these engagements are often named on one monument. From this angle, the additive war memorial is the most telling monument of our times, a confession of the violent pathology of modernity and the nearly comical, but in fact tragic, inability to face it in a mature manner. It is a confession that these Allied nations have not started what the Germans have been doing for well over a generation. There is no word in English for Vergangenheitsbewältigung, the German term for working through the past, particularly humanity’s most vile deeds.

This damning judgment does not come lightly. Yet it has been scripted into memorials for a surprisingly long time, particularly in the development of an additive memorial type: the “all wars” memorial. Thousands of them dot American towns and cities, but they can be found in Europe as well. The All Wars Memorial in Oberlin, Ohio, is both unusual and representative of the larger phenomenon. It dates to 1943, an odd moment to erect a war memorial. It reconstitutes spolia, or fragments of older construction, from a much earlier Civil War memorial. The original memorial of 1871 took the form of a sandstone Gothic spire with marble tablets engraved with the names of fallen soldiers. It stood at a prominent intersection in the small college town, across from the main public square, where both town and gown could encounter it. By the 1930s it had lapsed into near ruin—locals called it the “sunken church”—and it soon succumbed to neglect and antiwar sentiment common in the interwar period. It was dismantled in 1935, but the placards were saved, and even before Pearl Harbor a new memorial was planned for a verdant setting more removed from both commerce and college. The new memorial, a simple but dignified brick wall created to receive the old tablets, with ample room for future names, reflects the substantial changes in taste that took place between the 1870s and 1940s. Stone became brick; an assertive vertical monument became a horizontal surface; a Christian symbol became a pedestrian wall of names. It anticipated Maya Lin’s wall, but in the vernacular material of the riverine towns of the Midwest.

The more remarkable change has to do with the new conception of a memorial to all wars. By the 1940s Memorial Day practices in the United States were becoming increasingly institutionalized, largely under the purview of veterans’ groups such as the Veterans of Foreign Wars and the American Legion, whose numbers swelled after World War I. Dating back to Decoration Day, the predecessor to Memorial Day in the United States, commemorations frequently included parades and the movement of people from prominent civic spaces to memorials that afforded enough space for crowds to gather and a focal point where speakers could read poems, eulogies, and roll calls. They had to accommodate music and offer a place where veterans, widows, and gold star mothers could be made a visible part of the pageant. After World War II the old morbid cemetery and urban roundabouts and medians became troublesome places for these ceremonies. As wars piled up, survivors of one war overlapped with those of the next, and it became vital that these commemorations could be held at a single site where multiple generations could be accommodated. Hence the establishment of the “all wars” memorial as a type. These are open-ended memorials. They leave room to stitch future casualties into an unfolding history. Names continue to be added to Oberlin’s memorial. The most recent addition died in Kandahar, Afghanistan.

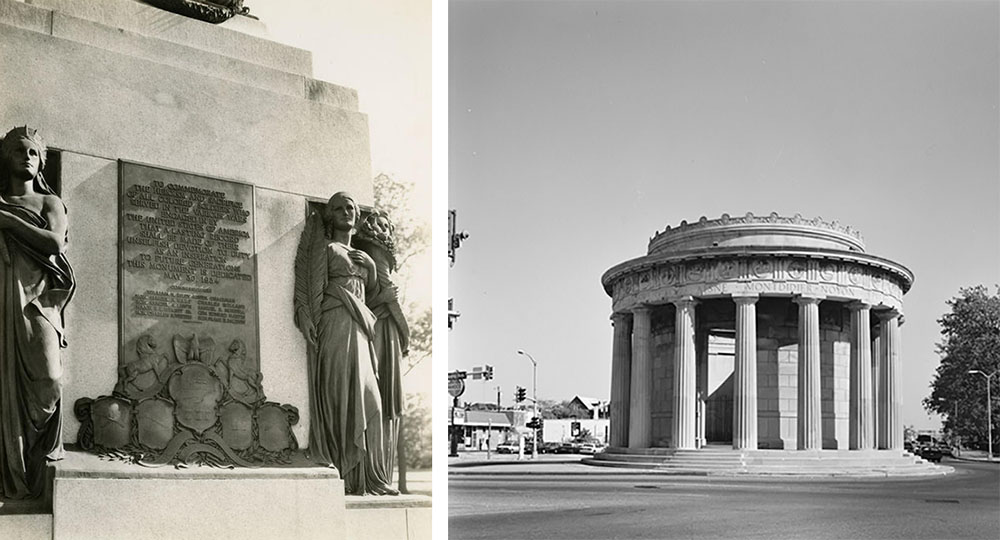

Memorials to all wars flourished under other more specific conditions, as well. The 42nd Infantry War Memorial in Boyle Heights, Los Angeles, was erected in 1949 “in memory of American soldiers of Japanese ancestry who fought, suffered, and died in World War II.” It served the local Japanese American community, which had used Evergreen Cemetery for generations because it was one of the few cemeteries that buried people of Japanese descent. Over the years, plaques have been added to the sides and back of the monument for Japanese Americans who died in the wars in Korea, Vietnam, and Iraq. While its name has not changed, it is effectively an “all wars” memorial for the Japanese American community, which continues to hold annual Memorial Day ceremonies there. The long history of Japanese Americans in Boyle Heights and in Evergreen Cemetery lend the site its gravitas, making a virtue of the cemetery as a site. The nearby Mexican American All Wars Memorial has a similar story. It was erected after World War II and has grown into the commemorative center for the Mexican American community. It now commemorates the 350,000 Mexican Americans who have died in military service since the Civil War. The two Boyle Heights memorials are ethnomemorials. For all of their importance for assembling their respective communities together, they also divide them from larger Memorial Day commemorations. As they muster, they also splinter. But this reflects the geographical divisions of Los Angeles, if not the reality of race and ethnicity in the United States.

A precedent for such ethnomemorials to all wars is the All Wars Memorial to Colored Soldiers and Sailors in Philadelphia, built in 1934. Possibly the earliest to be conceived as an “all wars” memorial, its promoters wanted to place it on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway, Philadelphia’s Champs Élysées. On this grand boulevard with museums, sculptures, and public spaces, the memorial would have joined other prominent monuments, including the new Civil War Soldiers and Sailors Memorial (1927) and the massive monument to George Washington that sits in a traffic circle in front of the Philadelphia Art Museum. In an era of acute racism, the city’s Art Jury blocked this prominent placement, while the Black community rejected the alternative, Fitler Square, which was seen as run-down and undignified. Instead, it was shunted to an isolated part of the sprawling Fairmount Park, where it could do no harm. In the 1990s, with a different political culture holding sway, it finally found its place on Benjamin Franklin Parkway, where it rejoined this larger memorial and cultural context. It now sits on a small plot in front of the Franklin Institute, a science museum founded in the nineteenth century, where it taps into the didactic and political role that urban memorials have played since the era of statuemania.

An even older “all wars” memorial reveals the sometimes banal surface of this convention. The obelisk in Oakdale, California, erected in 1929 by the Ladies Improvement Society, commemorates the American Revolution, Civil War, Spanish-American War, and World War I—even though Oakdale did not exist until 1871. No later wars have been added, probably because commemorations in Oakdale still take place in the cemetery, rather than at the memorial. It thus was defunct as a memorial from its inception. Visible from one of the main routes into town, it was but a pretext for beautification: war in a park, sponsored in the name of municipal beauty by women activists. Here war is nearly an abstraction, without name, place, or deed. To put a sharper edge on Oakdale’s intervention, in the country’s most isolationist moment, a monument to war—to all wars—seemed like the right note to interject into a small-town park. Apparently, isolationism did not preclude Americans from celebrating war or preparing its youngest citizens for it.

The recent Veterans War Memorial of Texas in McAllen shatters Oakdale’s abstraction in a bid for the most literal and forceful call to arms. It exposes the work that “all wars” memorials can do. McAllen has created much more than a memorial. It is a cultural landscape of war honoring “all those who have served in America’s wars of the twentieth and twenty-first century,” although it was later extended retrospectively to the American Revolution, despite the fact that McAllen was incorporated in 1911. Sponsored by the local chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution, it was conceived in much broader terms than most memorials as “an educational, cultural, and historic facility to assist future generations.” On a vast plot adjacent to the town’s convention center, a series of polished granite walls serve as text panels to tell the story of American war and patriotism, honoring the flag, the Constitution, the Declaration of Independence, and the “Founding Fathers.” Other walls extol abstract virtues such as valor and courage and, like many memorial walls, list names. The panels are arrayed around a 105-foot black American Spire of Honor, with statues here and there to George Washington, the Navy WAVEs and Army WACs, and individual Texas soldiers. More statues are planned. This is a memorial with mission creep, but that very fact illustrates what it means to assemble memory.

Memorials to all wars like the one in McAllen may still function strictly as memorials on certain days, but many of them host a dense thicket of assumptions, political ideologies, and civic ideals, as well as being part of a larger emotional geography with war at the center. McAllen’s memorial was fashioned ex nihilo to be a cultural landscape unto itself where people can wander into this thicket. Its autonomy as a place speaks to the desire to separate out this constellation of functions, ideals, and motives, to set it apart from the everyday more emphatically than memorials in parks, squares, and roundabouts typically have been. Of course, some of this goes to the horizontality of cities in the western United States, where land on the fringe is cheap, and the automobile changes the dynamics of where people drive memory into the ground. In this sense, nothing could be more ordinary. In McAllen, people get in the car to have this encounter, just as they do to go to the mall or supermarket. Of course, it makes all the difference that McAllen is a border town that aims its patriotic spectacle at a perceived enemy in an era of acute xenophobia. Seen from a Mexican perspective, it is an aggressive gesture.

It would be wrong to assume “all wars” memorials are an American pathology or a peculiarity of land use. The Monument to the Defenders of the Russian Land in Moscow (1995) lifts three bronzes representing ancient, tsarist, and modern Russian soldiers on a rough-hewn stone plinth. It sits in the vast memorial assemblage of Victory Park, but it is keyed to Defenders of the Fatherland Day, which itself has a complicated history that helps make sense of the memorial. This Soviet version of Remembrance Day began in 1919 to commemorate the creation of the Red Army. The day predictably expanded in scope after World War II, becoming Soviet Army and Navy Day, and changed again after the Soviet Union collapsed. In 2002 Vladimir Putin “Russianized” it and gave it its present name as part of a much broader propaganda effort to stimulate militarized patriotism in Russian society. Not surprisingly, it has come to mirror Putin’s masculinist rhetoric and self-display, doubling as Men’s Day. This explains why the Monument to the Defenders of the Russian Land, while sitting amid memorials to nearly every military conflict in Russian history, does not duplicate them. Its charge is different. The three soldiers tower over flowers that spell out the word Rus, forging a line of connection between the medieval Rus, tsarist Russia, and the “Great Patriotic War,” the Russian name for World War II. In leaving out the Russian Revolution, the monument conspicuously elides the Soviet moment.

The entire setting speaks to the shifting politics that the monument represents. Victory Park was conceived in the 1950s under Khrushchev, with its first monuments installed under Brezhnev, largely as part of the Soviet cult of World War II. The park languished under Gorbachev, when revisionist accounts of the Soviet role in World War II undermined the cult. Work resumed with special vigor in the 1993 as part of a post-Soviet project to glorify Russian national identity. The park opened and Defenders was unveiled in 1995 for the fiftieth anniversary of World War II. Like its American counterpart in McAllen, the Monument to the Defenders of the Russian Land is part of a post–Cold War realignment.

Excerpted from The Everyday Life of Memorials by Andrew M. Shanken, published by Zone Books. Copyright © 2022 by Andrew M. Shanken. Reprinted by permission.