Jacob Epstein with a bust of Kathleen, Lady Epstein, c. 1948. National Portrait Gallery.

Adventure-hungry music student Kathleen Garman arrived in London in 1919, eager to jettison the stifling conventions of her middle-class upbringing. The favorite of seven daughters and two sons sired by a Victorian-minded doctor—a devout Anglican who hoped, in vain, for curates as sons-in-law—eighteen-year-old Kathleen sought a more exciting life than she could possibly contrive in her depressed Midlands hometown. The social and creative whirl of postwar bohemian London, where kindred spirits in rebellion welcomed Kathleen and her sister Mary, was an excellent start.

Kathleen was an accomplished pianist and, like her siblings, had the gift of turning everyday life into a work of art. “They liked things to look effortless,” writes Cressida Connolly, author of The Rare and the Beautiful: The Lives of the Garmans. “Elaborate picnics appeared as if out of nowhere…They sent secret notes at midnight, and left the pillows smelling of scent.” The cheap Bloomsbury studio acquired by Kathleen and Mary was decorated with sketches and fragrant geraniums, everything lit, romantically but perilously, by naked gas flames. Making one’s surroundings as lovely as possible, “until we fall into the dust ourselves,” was a philosophy Kathleen would always live by.

Her own striking beauty reliably attracted attention: she had olive skin, masses of black hair, dark almond eyes, and high cheekbones, all belying her provincial English background. She accentuated her exoticism with dangling earrings and fringed shawls; people thought she was Spanish, Gypsy, or something. Supposedly, her mother was the illegitimate daughter of a lord and his Irish housekeeper. Yet this hardly accounted for Garman’s very un-English beauty, especially given that Marjorie Garman was pale and blue-eyed. Later relatives would have a family tree drawn up, convinced of some Jewish heritage—but nary a Jew could be found.

To the sculptor Jacob Epstein, himself the Lower East Side–born son of Orthodox Polish Jews, Garman resembled an Egyptian princess. The two first met at a London restaurant, the Harlequin in Soho, in the summer of 1921. She was twenty; he was forty and as notorious as he was renowned. His first public commission in 1908, for eighteen nude statues to adorn the British Medical Association building in the Strand, sparked a full-scale moral panic. Epstein’s sculptures, which included a bare-breasted young woman cradling her baby, were characterized by one London newspaper as “a form of statuary which no careful father would wish his daughter, or discriminating young man, his fiancée, to see.” Needless to say, people of both sexes flocked to this allegedly corrupting sight—craning their necks or peering from the top deck of buses, since the statues were forty feet above ground—as vehement attempts to shut down the half-finished project gathered pace. In the end, the puritans’ campaign failed. But Epstein was left jaded and exhausted, albeit wildly famous only a few years after launching his London career at age twenty-four.

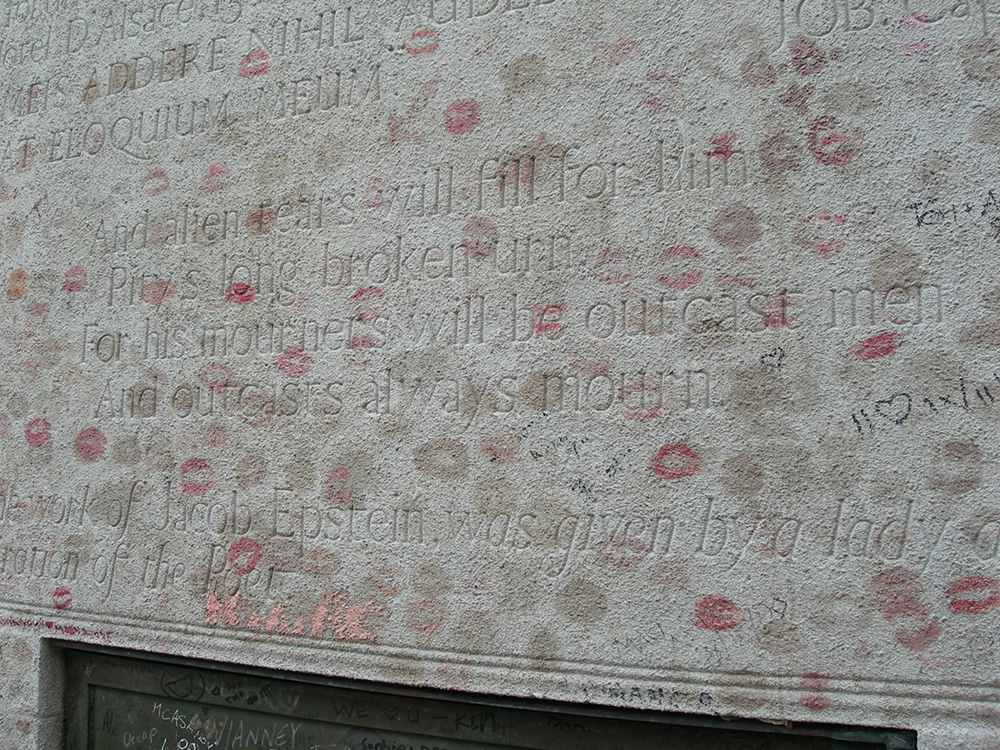

His rendering of Oscar Wilde’s tombstone provoked another scandal. The sphinx-like carved statue, positioned as if flying through the air on immense wings, was unveiled in London to acclaim in 1912. Once installed at Père-Lachaise in Paris, however, the work was pronounced indecent by the cemetery’s director, who covered it with a tarpaulin on account of the naked figure’s all-too-human testicles. Epstein, appalled and insulted, hastened to the site and removed the tarp. But the French authorities were unwavering: the monument was banned unless the offending genitalia were removed or concealed. Epstein viewed the accusations of indecency as patently ludicrous. The farce rumbled on for years, with organized protests and petitions for “the liberty of art” failing to reverse the ban. Only when war broke out was the dispute abandoned and Wilde’s memorial finally displayed as its creator intended. (Now protected by a “kiss-proof” glass barrier after the lipstick of successive Wilde pilgrims began to degrade the stone, Epstein’s modernist angel continues to divide artistic opinion.)

By the time Garman swept into Epstein’s life on a cloud of perfume and charisma, he was the most celebrated and vilified sculptor in Britain, known for his bold, borderline grotesque portraits. His style was to exaggerate facial concavities, convexities, and asymmetries, using a flat wooden tool on clay rather than his fingers. “Rarely have I found sitters altogether pleased with their portraits,” he wrote in his autobiography. “Understanding is rare, and the sitter usually wants to be flattered…On the whole, men sitters are more vain than women sitters.” He certainly had no problem finding women to model, nor to disrobe, recruiting them in nightclubs or even in the street.

Garman, already conscious of Epstein’s arresting stare from across the room at the Harlequin, received her invitation via a waiter: the gentleman wonders if she’d care to join him? She agreed, and Epstein asked if he could sculpt her. Incautious by nature and captivated by this intense American with disheveled hair, deep blue eyes, and a quiet voice, Garman needed little persuasion. No sooner had Epstein begun a study of her head than they were in love.

For Garman, who had left her sooty industrial birthplace in search of drama and transcendence, of newness, an epic romance with a controversial, iconoclastic artist must have felt like destiny unfolding. That Epstein was older and married, Jewish and foreign, and an obvious womanizer did not detract from his allure. Her horrified father, whose financial support allowed Garman and her sister to pay their rent and gad about with artists and musicians, threatened to disown her without a penny should she continue her ruinous liaison. She called his bluff, and her father capitulated, apparently incapable of staying angry with his favorite child.

Epstein’s wife presented more of a challenge. Nine years her husband’s senior, Margaret “Peggy” Epstein was a tough and intelligent Scotswoman with flame-red hair and a short, stout figure. When she first encountered Epstein in 1903 at a Paris dinner party, she was still married to her first husband, a barrister. Yet she pursued the young artist and within a couple of years had proposed to him. In accepting, Epstein may have viewed her solely as a maternal figure willing and able to take care of all life’s practicalities, a partner whom he’d value but who didn’t inspire romantic lust. Epstein’s younger sister Sylvia thought that “he treated her like a dog. But he respected her because she mothered him, and he stayed married to her because of that.”

Nothing if not pragmatic, Peggy obeyed the customary and (then as now) culturally sanctioned decree of the Great Male Artist: that sexual fidelity is a hindrance to male creative genius and therefore must be deprioritized. She went so far as to welcome other women as residents of their Bloomsbury household, and chose to raise Epstein’s first love child, a daughter by his erstwhile muse Dorothy “Meum” Lindsell-Stewart, as her own. Peggy, opined one live-in model, “exists solely for her husband, his interests are hers, his genius is the only god she recognizes, and she deems the world well lost for his sake.”

According to the memoirist Viva King, a frequent visitor to the Epstein ménage, Peggy was known to mother her husband’s mistresses “as a loving Eastern wife No. 1 would look after a new concubine in the harem.” But when Garman entered Epstein’s life, the whole precarious system began to founder—because this time he was truly obsessed, as his lovesick letters reveal:

I have your note and the news that you arrived home. I love to read what you feel and that you know my happiness was so extreme that were I to die then and there I would be an image of supreme happiness in death. I still live in the night the three nights we were together…Your nearness, your glances, and every touch of you fills me with joy…

From the outset, Peggy realized that Garman was more than a passing fancy on the part of her husband. Nor would this headstrong girl be susceptible to the older woman’s tactical domination and stage-managing. The situation had no precedent in the Epsteins’ fifteen-year marriage, and Peggy must have felt as though her whole existence was set to crumble. She enlisted waiters at the Harlequin as spies and tried spreading rumors that her rival was flighty and unfaithful—a ploy that, unsurprisingly, only served to heighten Epstein’s fixation. “My hell is almost as intense as the heaven I’ve been in,” he wrote to Garman. “When you say they are liars I believe you. I want your love and without it I would be the unhappiest man on earth.” Peggy even railroaded King into posing naked in Epstein’s studio, praying that the lovely twenty-eight-year-old would, as King put it, “distract her Epstein from a real and terrible menace to her life.”

But Epstein was not to be diverted. The affair showed no signs of fizzling, and during its first year or so he had completed two busts of Garman. The second, depicting her open-mouthed and heavy-lidded, head slightly back as though reclining in ecstasy, may have proved a flash point for Peggy’s temper. Epstein’s biographer Stephen Gardiner writes that while Peggy “would never have damaged any of her husband’s works, however angry she felt, she might well have done her utmost to damage the subject of this portrait of what was plainly a profoundly pleasurable sexual relationship.”

When Garman received a letter from Peggy summoning her for a talk, the prospect would have been singularly unappealing. Still, she wasn’t one to shy away from confrontation—and she couldn’t have imagined that her life was in danger. But when she arrived at the Epsteins’, Peggy marched her into a room, brandished an antique pistol, and fired. Presumably aiming for Garman’s heart, instead she hit her left shoulder. Shocked and bleeding, Garman managed to flee and was taken to hospital. artist’s model shot announced the newspapers the next day. She made a full recovery following surgery, though some of the bullet remained embedded in her shoulder, but was scarred for life. Epstein paid her medical bills and, keen to avoid further publicity and any undue disruption to his routines, persuaded her not to press charges. His work would always matter more than a women’s squabble, even a murderous one.

Garman, though doubtless guided by Epstein’s wishes, was too much of a private person to welcome the fuss and attention of a court case anyway. She even agreed to ride through Hyde Park with Peggy in an open taxi in an attempt to shut down gossip about the acrimony of their love triangle. The traumatic incident was eventually mythologized by Garman’s beautifying signature. A bowl of scarlet roses was on the table when the bullet was fired, she would tell people, and she mistook splashes of her blood for falling petals.

In the wake of this climax to the hostilities, a kind of détente was established, allowing the two relationships to continue in tandem. Epstein would spend Wednesday and Saturday nights with Garman, arriving with wine and flowers and leaving at dawn. In 1924 they had their first child, a boy named Theodore, followed by Kathleen—known as Kitty—in 1926 and Esther in 1929. (A fourth child died of SIDS as a baby.) Garman was essentially a single mother to their children, and since space in her small studio and money were both in short supply, she sent Kitty to be raised by her own mother, Marjorie, whose two youngest daughters were still at home. Esther spent her early childhood with Garman’s old nanny in the West Midlands; only Theo stayed in London with his mother.

Over the ensuing years, Garman and Epstein led connected yet independent lives, which sometimes meant other affairs. In 1934 Epstein’s second son was born to Isabel Nicholas, one in a series of young lodger-models taken up by Peggy, who remained ever hopeful of breaking the bond between her husband and Garman. Although that hope came to naught, Garman too saw other people; Connolly describes a lengthy amorous attachment to a smitten young Italian: “Volumes of poetry, in English and Italian, were exchanged as gifts, and he wrote poems to her and drew her portrait.”

As Connolly’s entrancing book records, Kathleen and her siblings were ruthlessly allergic to humdrum domesticity and monogamy. The youngest and most beautiful sister, Lorna Garman, was married with two children when she had overlapping affairs with Lucian Freud and Laurie Lee. Her older brother Douglas, while separated from his wife, set up home in the Sussex countryside with the American heiress and future art patron Peggy Guggenheim, who was named in his divorce. Bisexual Mary, whose husband was the poet Roy Campbell, had a torrid fling with Vita Sackville-West, much to the jealousy of her lover Virginia Woolf. “No other contemporary women,” marveled Campbell of Mary and Kathleen, “ever had so much poetry, good, bad and indifferent, written about them, or had so many portraits and busts made of them.”

Yet a charmed life, however liberated and colorful, is no guarantee against sorrow. Theo, a gifted and sensitive painter who suffered from schizophrenia, died suddenly at age twenty-nine in February 1954. His sister Esther fell into a deep depression, compounded by the death of a friend that same year, and committed suicide nine months later. She was just twenty-five. This double tragedy seems to have brought their parents closer, rather than tearing them apart. Though Peggy had died in 1947, after a fall and years of poor health, it wasn’t until 1955 that Epstein and Garman married in a quiet London ceremony. noted sculptor weds model ran one headline. Epstein had recently been named a Knight of the British Empire, which meant those lifelong arch-bohemians were now to be addressed as Sir Jacob and Lady Epstein.

If Garman’s love affair was long, her marriage was brief: Epstein died four years after the wedding, at age seventy-eight. Garman assumed control of his legacy, overseeing exhibitions and donating two hundred of his plaster casts to the new Jerusalem Museum of Art, where they were placed in a specially built pavilion. Unflagging in her energy, Garman set up a public art gallery at the Walsall Library, near her family home, in 1974. “I feel we are dealing with dreams,” wrote Garman, “and are about to house them in a solid Midlands setting for posterity. How delightful.” Now housed within the New Art Gallery in Walsall, the permanent display comprises a significant body of work by Epstein alongside pieces by Theo Garman, Lucian Freud, Modigliani, Renoir, and Van Gogh.

Epstein’s seven Kathleen sculptures, the first of which he began the day after they met, are held in various public and private collections and occasionally change hands for modest sums at auction. Sixth Portrait of Kathleen, a green patinated bronze bust of Garman at around age forty, breasts bare and elongated hands aloft, fetched $4,375 at Christie’s New York in 2016. Bonhams Los Angeles sold another version in dark bronze for $9,375 last year.

Epstein and Garman’s daughter Kitty, in apparent testament to the combined powers of cultural and genetic determinism, is the subject of some of the most valuable artworks in the world. Like her mother, as a young woman Kitty fell in love with a libidinous Jewish artist of immense talent and rampant ego: her aunt Lorna’s former paramour Lucian Freud. They married when Kitty was twenty-one and Freud was twenty-five, and divorced after four years. During their relationship Kitty, who would exhibit her own sketches and paintings only much later in life, sat for many of Freud’s most famous paintings, including Girl with a White Dog and Girl with a Kitten, both in the collection at Tate Britain.

While working to ensure Epstein’s place in posterity, as a widow Garman also ran a small commercial gallery in Kensington and traveled often to France and Italy. Shaping her own future remembrance was never of interest; she dismissed the idea of writing a memoir and gave one prospective biographer short shrift, telling him, “I can’t even discuss such a ridiculous proposition.” To Garman what mattered was alchemizing joy from the present moment, not chronicling it, and until her death at age seventy-eight—the same age as Epstein, but twenty years later—she never stopped making an art of life itself. “Such colors glowing, smoldering, sparkling in the evening sunlight as I have never seen,” she wrote during a visit to Lake Garda. “I drink it all in like wine burning through my veins.”

A friend reminisced to Connolly that the “very dramatic” Garman “had presence, and when she walked into a room she was magnetic…But she devoted her life, really, to that man and his work. All Epstein wanted to do was work. Her life was almost a sacrifice to him, to his art.” The beleaguered female muse, her existence vampirically subsumed within the orbit of her selfish artist lover, is for good reason a familiar trope. As Marina Picasso writes of the women involved with her grandfather, “After he had spent many nights extracting their essence, once they were bled dry, he would dispose of them.” But Garman, far from being bled dry, always seemed to obey her impulses and follow her passions to an enviable degree. If she had any regrets, it’s hard to imagine that Epstein was one of them.