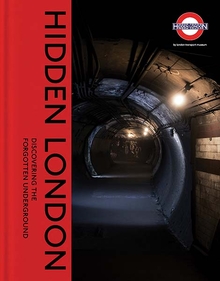

Down Street London Underground station, 2019. Photograph by Sheep“R”Us. Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0).

As passengers on the Piccadilly line hurry between Green Park and Hyde Park Corner, few are aware of passing through the disused Down Street station, let alone of this station’s role in Britain’s war effort between 1939 and 1945. Yet Down Street was adapted as the bunker headquarters for national railway operations during the war—a vital, secret, and secure communications hub for coordinating freight, troop, and passenger trains. As trains passed the former station, key figures in the national war effort met in offices and meeting rooms on the platforms and in the passageways. Dormitories, dining facilities, and bathrooms were provided for staff, who worked safely below ground, interrupted only by passing trains. In October 1940, the prime minister himself, Winston Churchill, dined and sheltered here overnight as the Blitz raged above in nearby Whitehall and Piccadilly.

The devastating effects of modern aerial warfare were seared into the public imagination on April 26, 1937, when German and Italian aircraft attacked and effectively destroyed the city of Guernica in a single day of raids during the Spanish Civil War. Britain had already suffered bombing from aircraft during the World War I, and civilians had reacted by seeking improvised shelter. Fortunately for the capital and the country, the government, led by those who had lived through the earlier conflict, had been discreetly planning defenses and preparing for the worst long before it became a reality during the Blitz. As the threat of war intensified, so did London Transport’s efforts to strengthen its network in readiness for the expected bombardment. A catalogue of disused stations had been prepared in 1929 to answer a future emergency. Down Street and stations like it would play an essential and secret role in supporting Britain’s war effort by allowing essential services to be coordinated without interruption.

The rapid expansion of privately owned Tube lines in the Edwardian period led to the construction of many Underground stations across the capital. Some would prove to be financially unsuccessful due to their location, awkward design, or proximity to rival stations. Four stations situated on the Piccadilly line—at Down Street, Brompton Road, Dover Street (now Green Park), and York Road—were fully abandoned or heavily modified from their original state in the early 1930s. These lesser-used stations were closed to speed up the service through the city center following the extension of the line north and south into the suburbs. Their elevators were removed, and the platforms, elevator shafts, and passageways became ventilation shafts for the busy Tube.

London Transport saw the wartime potential of such large spaces belowground as bunkers for coordinating transport; the idea of using them as civilian shelters came later. The tunnels were about sixty-six feet or more belowground—deep enough to provide protection from the most powerful German bombs. They were also connected by the Piccadilly line, meaning that personnel and telephone cables could easily pass between sites, safe from the air raids above. As the Blitz threatened to bring the capital to a halt, one by one the dormant stations on the Piccadilly line and elsewhere were called up for duty, adapted for reuse, and connected to key civilian and military installations by telephone. The wartime role of these bunkers was kept secret at the time, and as their stories emerged in postwar years, they were characterized as interesting individual sites rather than as part of a resilient, distributed, and connected network.

Down Street station sits on a quiet side street in London’s affluent Mayfair. Its somewhat awkward design and lengthy passageways to the platform meant that it struggled to attract passengers from the day it opened in 1907. The remodeling of neighboring stations at Dover Street and Hyde Park Corner in the early 1930s, with the installation of escalators, brought the entrances of these stations closer to Down Street. This was the final blow to the station’s future, and in May 1932 it was closed for passenger use and quickly converted into a humble ventilation shaft.

Railways were the arteries of British transport in the 1930s and vital for the logistical effort associated with the impending war. As in World War I, the coordination of the privately owned railway companies was overseen during the new conflict by a government department: the Railway Executive Committee (REC). Its members were drawn from the senior management of Britain’s “Big Four” mainline railways—London & North Eastern Railway, London Midland & Scottish Railway, Great Western Railway, and Southern Railway—together with representatives from London Transport. The REC headquarters were initially run from Fielden House on Great College Street, very close to the Houses of Parliament. The chairman of the REC, Sir Ralph Wedgwood, had served with the Committee during the First World War and was aware of the need to prepare the headquarters for whatever aerial bombardment might come. He instructed the REC secretary, Gerald Cole Deacon, to make the necessary preparations. These included plans to reinforce and bombproof the basement of Fielden House to protect its large telephone exchange, essential to the coordination of the nation’s railways.

By 1939 Cole Deacon had been advised by the London Metropolitan Police that the building was unsuitable for conversion as a bombproof facility due to its shallow basement. There was concern, too, that the proximity of the river Thames and Houses of Parliament made the building a potential collateral target. Cole Deacon sought alternative premises with good provision for telephone lines. Discussions with London Transport quickly led him to seek permission to convert Down Street station into underground headquarters truly fit for purpose. The design features that blighted Down Street as a passenger station—deep, lengthy passageways and discreet location—made it ideal as a bunker from which to run the nation’s railways, undisturbed by the destruction wreaked above. On April 28, 1939, Frank Pick, chief executive officer of London Transport, approved the conversion in principle, and the race was on to convert the site before war was declared.

By the time war was declared on September 3, 1939, the facility was sufficiently finished to allow a skeleton staff to move in. As the works were completed over the following months, the core staff and operations of the REC moved belowground to Down Street.

The weeks before the site was fully completed were uncomfortable for staff, but by comparison with most civilian shelters, the REC enjoyed extremely well-appointed facilities, with air-conditioning, private bedrooms, kitchen, and separate bathrooms and mess rooms for senior executives and lower-ranked officers. In January 1941 the Railway Gazette was, surprisingly, given permission to write an article about the facility, provided with a full set of plans, and allowed to take photographs throughout the site. Publication was delayed due to belated security concerns from the REC, but the article was eventually published in November 1944 and provides a remarkable record of this secret headquarters. It is notable that one photograph, captioned as the executive mess room, looks lavish for a bunker but is in fact the neighboring mess room for lower-ranking officers—a sign perhaps of some sensitivity about portraying the full grandeur of the paneled, wallpapered executive mess during a time of war.

The noise of the Piccadilly line running through the station, just inches away from meeting rooms, the telephone exchange, and bedrooms, meant that life in the bunker was difficult for those working and sleeping there full-time. Nonetheless, the facility allowed the REC to do its job regardless of air raids and, a year after opening, its effectiveness as a bunker meant that it would protect an extremely important guest.

In early October 1940, the Blitz moved west, from the docks and East End to Whitehall. On the night of October 15 came the most sustained attack yet on the governing center of the country. A bomb fell on the Treasury and killed three officials. The prime minister’s official residence at 10 Downing Street was badly damaged, though staff were saved, having been ordered to the shelter only minutes before. A high-explosive bomb fell only a few meters from No. 10.

The Cabinet War Rooms were not strong enough to act as a shelter, and while the War Rooms was being reinforced and No. 10 patched up, the prime minister was temporarily without a protected central London shelter. To the consternation of the War Cabinet, Churchill was a reluctant shelterer and was keen to pursue “business as usual” as far as possible at Downing Street, to support public morale.

On this occasion he allowed himself to be persuaded by his cabinet colleague Josiah Wedgwood (brother of Sir Ralph Wedgwood) to take refuge in the REC headquarters until more suitable accommodation could be provided. Churchill later recalled, “I used to go there to transact my evening business and sleep undisturbed.” But despite the comforts available at the REC, internal memos and oral history accounts suggest that the need for secrecy led to Churchill’s camping in Cole Deacon’s office at night, rather than sleeping in the staff bedrooms at platform level.

According to the personal diary and oral accounts of Churchill’s private secretary John Colville, the prime minister spent at least eight nights at Down Street station between October 23 and December 20, 1940, by which time the Cabinet War Rooms’ reinforcements had been completed. The occasions Colville describes when he himself or the prime minister were present at Down Street show that the REC treated Churchill very well as their guest, with caviar, champagne, and vintage brandy on offer, presumably provided from the stores of the railway hotels. The diary suggests that the opulent conditions at Down Street allowed Churchill to conduct business in his favored manner—over dinner and drinks, with key figures such as Minister of Labor Ernest Bevin—in the same way he had at 10 Downing Street in the months prior. Colville recalls that other members of the War Cabinet and War Office were invited to the REC bunker; a diary entry for the night of October 30 records that Churchill and Bevin dined there, had been well plied with brandy, and had great difficulty operating the elevator. Once outside, the prime minister was nearly arrested in the street for arguing with a police officer about having car sidelights that were too bright.

Colville described Down Street as “the safest place,” in stark contrast to civilian life on the surface. During the Blitz, Madeleine Henrey lived with her husband Robert and their baby son in a luxury flat in Shepherd’s Market, less than a hundred meters from Down Street. She published an invaluable account of their village’s and neighbors’ experience of nightly bombing and fires:

We became accustomed to the sudden drone of an airplane in the middle of the morning, the screech of a bomb, the dull crash of its explosion, and the smell of cordite…Each morning it became a rite to visit neighboring damage…the road squads were still sweeping away the shattered glass and the hosepipes of the Auxiliary Fire Brigade lay snakelike from pavement to pavement.

One night in November 1940, a bomb fell several streets away from the flat and shattered the windows in their spare room: “the glass pounded to shreds and driven like nails into the opposite walls.” For civilians in the Blitz, even a near miss could be deadly. When compared with the experience of life working in heavily protected bunkers, it is easy to see why Churchill wrote of feeling “a natural compunction at having more safety than most other people.”

During this time, the War Cabinet were in process of commissioning of civilian deep-level shelters, while Churchill was still using Down Street as an occasional bolthole. The REC headquarters clearly left a good impression on the prime minister and his staff. He wrote fondly of his stay at Down Street and, according to Colville, nicknamed the site “the burrow.” As a parting gift on December 21, 1940, he sent £10 to the REC for their Christmas fund.

Churchill adopted a policy of making his movements unpredictable in response to personal danger. His private secretaries rarely knew far in advance where he was going to settle for day or nighttime work; they had to be ready at any moment to scuttle after him with the relevant papers. At the end of October 1940, John Colville recalls a colleague, John Peck, writing a spoof memo in the style of Winston Churchill:

ACTION THIS DAY

Pray let six new offices be fitted for my use, in Selfridge’s, Lambeth Palace, Stanmore, Tooting Bec, the Palladium, and Mile End Road. I will inform you at 6 each evening at which office I shall dine, work, and sleep. Accommodation will be required for Mrs. Churchill, two shorthand typists, three secretaries, and Nelson [black cat resident at 10 Downing St]. There should be shelter for all and a place for me to watch air raids from the roof. This should be completed by Monday. There is to be no hammering during office hours, that is between 7 am and 3 am W.S.C.

In January 1941 a genuine request came to the REC from the prime minister, asking for the only remaining empty passageway at Down Street to be converted for his use, “as speedily as possible.” Churchill’s request was enough to overcome London Transport’s objection to building a suite of offices and accommodation in the second ventilation passageway. The REC and London Transport delivered this request in less than six weeks, at a cost of more than £7,000 and in great secrecy. Physical evidence survives in this passageway showing that the works were carried out using similar methods as for the rest of the headquarters, while employing techniques also used in conversions elsewhere, at Dover Street, for example.

Most of London Transport’s records and plans of this secret project were subsequently destroyed, but a special requisition financial note reveals that the accommodation contained a suite of bedrooms, dining room, conference room, kitchen, and meeting rooms. On August 30, 1941, Churchill wrote to the chairman of the REC to thank him for his hospitality of the previous autumn, and the note reveals that he had yet to return to visit his special premises. Here the trail goes cold—no firm evidence has yet been found of who may have used the conversion from this point onward.

Adapted from Hidden London: Discovering the Forgotten Underground by David Bownes, Chris Nix, and Siddy Holloway with Sam Mullins, just published by Yale University Press. Copyright © 2019 by Yale University Press. Reprinted by permission of Yale University Press.