Mortar and pestle, Iraq or Afghanistan, thirteenth century. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Nasli M. Heeramaneck Collection, gift of Joan Palevsky.

Al-Mukhtar ibn al-Hasan ibn Butlan was born in the early part of the eleventh century, probably in Baghdad. In all likelihood a Nestorian Christian, he was the star student of the most celebrated philosopher-doctor of the first half of the eleventh century, the Nestorian priest Abu l-Faraj Ibn al-Tayyib. Ibn al-Tayyib was a prolific writer and teacher of medicine, philosophy, and logic, and many of his voluminous writings were commentaries on the Aristotelian corpus. This depth of knowledge had a great influence on Ibn Butlan, who became a polymath in his own right.

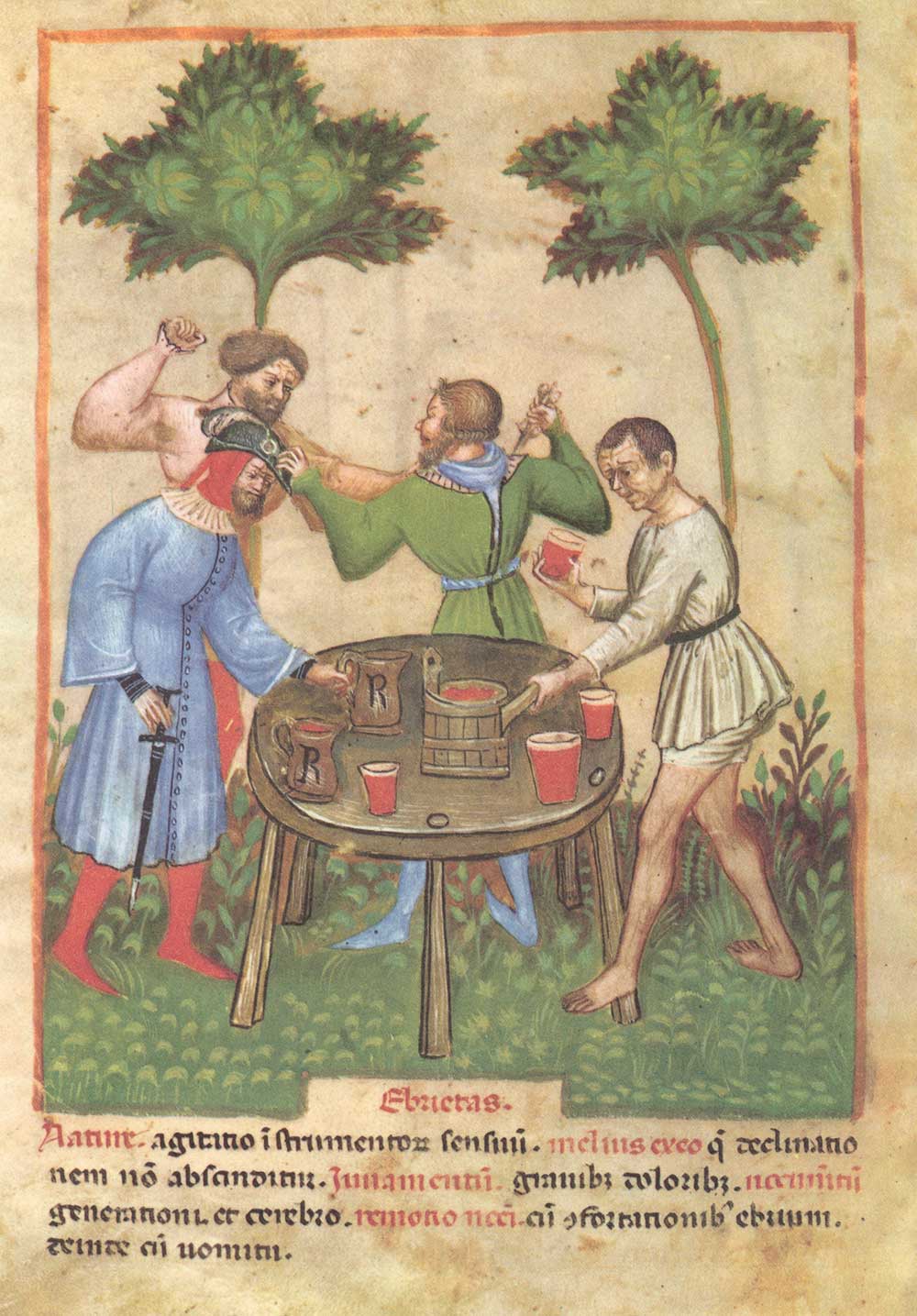

Ibn Butlan’s most famous work is his Almanac of Health, a medical work composed around 1046, which garnered him fame in the Latin West until the early sixteenth century. Its organizational framework, within a scheme of Galenic humoral medicine, was as important and innovative as were its contents, which he arranged in tables, probably under the influence of earlier astronomical works. These tables represent the broad essentials of a healthy life, ranging from hygiene and dietetics to environment and exercise.

In the late winter of 1049, a few years after the death of his mentor Ibn al-Tayyib, Ibn Butlan left Baghdad and headed for Cairo, which he reached in the late autumn. There is little doubt that Ibn Butlan made the trip to Cairo in order to seek out the famous physician Ibn Ridwan. He was already aware of Ibn Ridwan’s often polemical compositions about Galenic humoral medicine, books that criticized the works of others. Ibn Ridwan was a powerful figure, and Ibn Butlan hoped for a reception in Cairo that would boost his flagging career prospects. Ibn Butlan’s first meeting with Ibn Ridwan, at the palace of a Fatimid minister, was amicable and professionally courteous, but when Ibn Ridwan showed little sign of promoting Ibn Butlan to the position to which he aspired, Ibn Butlan made the mistake of writing an open letter to the medical community of Cairo. It was not an ad hominem attack, but he did make remarks that incensed Ibn Ridwan, especially in the criticism he leveled against one al-Yabrudi, a Damascene physician who had published a treatise stating that the hatchling of a bird is warmer than that of a chicken. The debate had its roots in Greek natural science; Ibn Butlan maintained that movement produces heat, and since the young chicken moves about independently immediately upon hatching whereas a young bird is helpless, the young chicken has the warmer constitution. There was no real cause for Ibn Butlan to devote so much space to the subject in an open letter.

Ibn Ridwan’s reply was vitriolic, accusing Ibn Butlan of being a mediocre doctor and an improperly trained physician. This triggered a defensive and detailed reply by Ibn Butlan in which he called into question the very nature of Ibn Ridwan’s training, pointing out in blunt terms that proper training as a doctor came from reading widely under the tutelage of an elder mentor who could correct one’s mistakes and misapprehensions about medicine: Ibn Ridwan was entirely self-taught. Ibn Ridwan wrote four more letters in response, two of which survive, including one in which he advises all the doctors of Cairo to shun the pretentious visitor. Ibn Butlan was obliged as a result of these intemperate exchanges to leave Cairo never to return, his hopes for advancement there stymied by his own rashness. Interestingly, religion—Ibn Ridwan was Muslim, Ibn Butlan Christian—appears to have played no part in the poisonous correspondence between the two men.

Sometime before 1054, Ibn Butlan returned the way he had come, but he turned westward after Antioch and headed for Constantinople. The year 1054 is also when plague struck the Byzantine capital and spread across the Near East. This is significant in the context of The Doctors’ Dinner Party, excerpted below. When Ibn Butlan describes, fictitiously but feasibly, a town in northern Syria as completely cleansed of plague, it must therefore have been sometime before 1054. We believe this supports the argument that Ibn Butlan composed The Doctors’ Dinner Party during his time in Cairo, or even before he arrived there, as the first of two works partly reflecting his contretemps with the irascible Ibn Ridwan.

The plot of The Doctors’ Dinner Party is simple, belying the sophistication of the work. A young man appears in the town of Mayyafariqin, in the Diyar Bakr region that straddles western Anatolia and northern Syria. He has traveled there on foot from Baghdad, destitute and seeking work as a physician. He soon encounters an older man in the marketplace, who eloquently and courteously receives him and, after a brief discussion, invites him home for a meal. The young stranger claims he has an ailing stomach and will not be able to eat. This is central to the old fellow’s invitation, for he turns out to be an atrocious miser, and a dinner guest who cannot consume food is a glorious find for a miser in search of company.

The following comes from the tenth part of The Doctor’s Dinner Party, “On the Rejection of a Certain Doctor and Those Who Vilify Him,” and begins with the host complaining about another young doctor.—Philip F. Kennedy and Jeremy Farrell

When they had drunk their fill, our host said to me, “Good sir, listen to this story. I had a patient whose condition worried me, so I stayed by his side day and night, observing his behavior, watching for signs of his illness, gauging their relative strength and weakness, and tracking his various symptoms, good and bad. I examined his urine samples and compared the various residues, one consistency against the other, one color against the other—all this to be able to discern the end of the onset of his illness, its worsening and its eventual decline. My goal was to use the right medicine at the right time, and not to find myself on one path, so to speak, and the disease on another. I didn’t want to be like a dentist who pulls out a healthy molar instead of the one that has decayed.

“I monitored his medications, liquids, plasters, and air quality, because a doctor needs the courage of a soldier joining battle when he sees a patient, having prepared all manner of things for his own protection and for combat. He does not know his enemy, after all, neither the weapons he uses nor the ambushes he is planning. So it is with a doctor: When he visits a patient he must know the constitution of his body, the state of his limbs and organs, the ailments that can afflict them—their causes, their treatment, the medications that can cure them, and the substitute medications in case the primary treatment is not available. He must know how to produce them and how they are to be applied, cognizant of the equivalence between symptom and dose, and how to make adjustments according to their properties.

“The young man in question imposed himself on my patient, asking his visitors questions, and requesting prescriptions from friends to the point that my patient dispensed with my services and engaged him as his principal physician. God knows, this came as a relief to me as well as to his servants and to the apothecaries with whom I had been dealing!

“I was not jealous, but you would not believe me if I were to say that I was not furious. As the saying goes, ‘The most aggrieved is the one supplanted by one less worthy.’ But this kind of mistreatment has through the ages tormented so many colleagues in this profession. The way an incompetent man attains his goal is exactly how the resolute expert is kept from his objective. In any event, they say a decent person leaves in good faith when his path is blocked. It is best to forbear when there is no hope of changing a situation and when all patience has been exhausted.

How can I be patient when I observe

my enemies tipping the scales against my success?

“I now believe that this upstart doctor is like a ninety-five-year-old who has never properly treated a patient. He knows no rules and has never plowed the field of medicine. He treads another path completely and knows nothing of the manner in which doctors tend to their patients. Nothing of the kind has ever occurred to him: he has neither heard of our ways nor thought to practice properly.

“If you believe all this, it might seem to you that I’m defaming him. But after I left, I heard that this charlatan did alter my treatment; he did not follow my procedures, choosing instead to show off his own method. The patient is without question in a terrible state, but people in our time get the doctors they deserve, like this one, cunning and wretched.

“I have heard he will not even speak to someone without weighing the money due to him. How different he is from us, we who consider the sick to be our children and our brethren. Heavens! If you were to see me at prayer, you would see something truly amazing. As you know, some implore God for abundant wealth and others for a virtuous death. As for me, I stretch out my hands and ask for a clear urine sample, normal saliva, plentiful perspiration, copious urination, and healthy defecation. During my late-night prayer, I beseech: ‘Lord, when my patient so-and-so suffers delirium tonight, may he sweat copiously, and as for so-and-so, who suffers from gout, bless him with restful sleep.’ ”

“Sir,” I said, “ask God to provide you with a livelihood that will eliminate the need for this.”

The old fellow laughed and said, “You’re like the man who suffers from colic and spends his night asking God to bless him with flatulence, but when he despairs of any relief his last resort is to beseech, ‘Lord, grant me Paradise.’ His doctor will say, ‘You spent the whole night asking God for a fart and He didn’t answer and now you ask for Paradise, the heavens, and the earth! You could have signaled to me what you prayed for—and if my prayers were answered you would be saved. Instead, the patient for whom I wished the reprieve of diarrhea still suffers from colic and the one for whom I wished a purgative sweat is afflicted remorselessly with fever. The reason these supplications fail is that people pay us nothing, so we pray without purity of intention.’

“God protect us from the stagnant practice of doctors and the sincerity of the sick. All the same, I have had discussions with this scoundrel, as he knows full well and cannot deny. For instance, I asked him one day in jest, ‘Why are a dog’s feces useful in the tanning process, a cow’s dung useful in the fuller’s craft, a wolf’s droppings useful in the treatment of diphtheria, and a lizard’s excrement useful in the healing of ulcers?’ My questions left him speechless. I took the opportunity to vex him with another question: ‘Why is mere water sufficient to clean one’s hand after defecating despite the repugnance of excrement, and yet after a good meal the odor of food can only be purged with water scented with perfume or with a detergent of sedge and alkali?’ ‘I don’t know,’ he replied. ‘Why,’ I asked, ‘does urine tend to thicken and become cloudy when cold whereas fruit juices become clear and flow freely?’

“He interrupted me and began to grind his teeth, regretting his misspent youth, when his wood was still green and supple and his clay still ductile and malleable. He felt the remorse of the young man mentioned by Galen.”

“What young man?” I asked.

And he answered, “Galen said that a young man whose beauty distracts him from study and who is abandoned by his loved ones when he has lost his looks will cry out in remorse, ‘I wish I had never been handsome!’ ”

“You should know that there are three categories of backward students in this profession. The first reads profusely but nothing is imprinted in his mind—he is like a convalescing patient who thinks he will benefit from overeating, ignorant of the fact that that he needs healthy limbs and organs to absorb the food and put on weight: he eats avidly but his body remains unchanged. The second reads a lot but understands little; he is like a glutton whose consumption bloats his figure, which diminishes his strength and makes his limbs heavy. Such an ignoramus is of two kinds: one knows where he stands and therefore does not seek advancement, fully aware of his deficiencies, limiting himself to prescribing pips and oxymel. The other is proud in his ignorance, yet is like a swollen scholar who is clearly overweight and struggles as a result:

A man may dress elegantly,

but denuded he is just a wretch.

So too a person with rosy cheeks

may suffer from inflamed lungs.

“This is why Galen said, ‘Ignorance of one’s own ignorance is ignorance twice over.’ Suppose we concede that he is indeed learned; what good is that without the ability to practice? They say there is nothing more damaging for a patient than a physician who talks a good game but cannot actually practice. A practitioner who finds it hard to articulate his diagnosis may in fact have the talent and experience, while a charlatan who elicits admiration with his eloquence and good manners may produce unwelcome consequences. Any doctor who relies in his treatment on affected speech and who spouts excuses when the patient risks dying without the appropriate care is like a man who drinks poison wittingly and relies on having the antidote. It is patently clear that sound knowledge is only realized in good practice. The sick man who knows the remedy for his illness does not profit from his knowledge if he fails to take the remedy: for him, neither respite nor recovery—quite the contrary!”

Excerpted from The Doctors’ Dinner Party by Ibn Butlan, translated by Philip F. Kennedy and Jeremy Farrell, published by NYU Press, Library of Arabic Literature. Copyright © 2023 by New York University. Reprinted by permission.