The Jungle Book, c. 1900. The New York Public Library, The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs, American Book Posters.

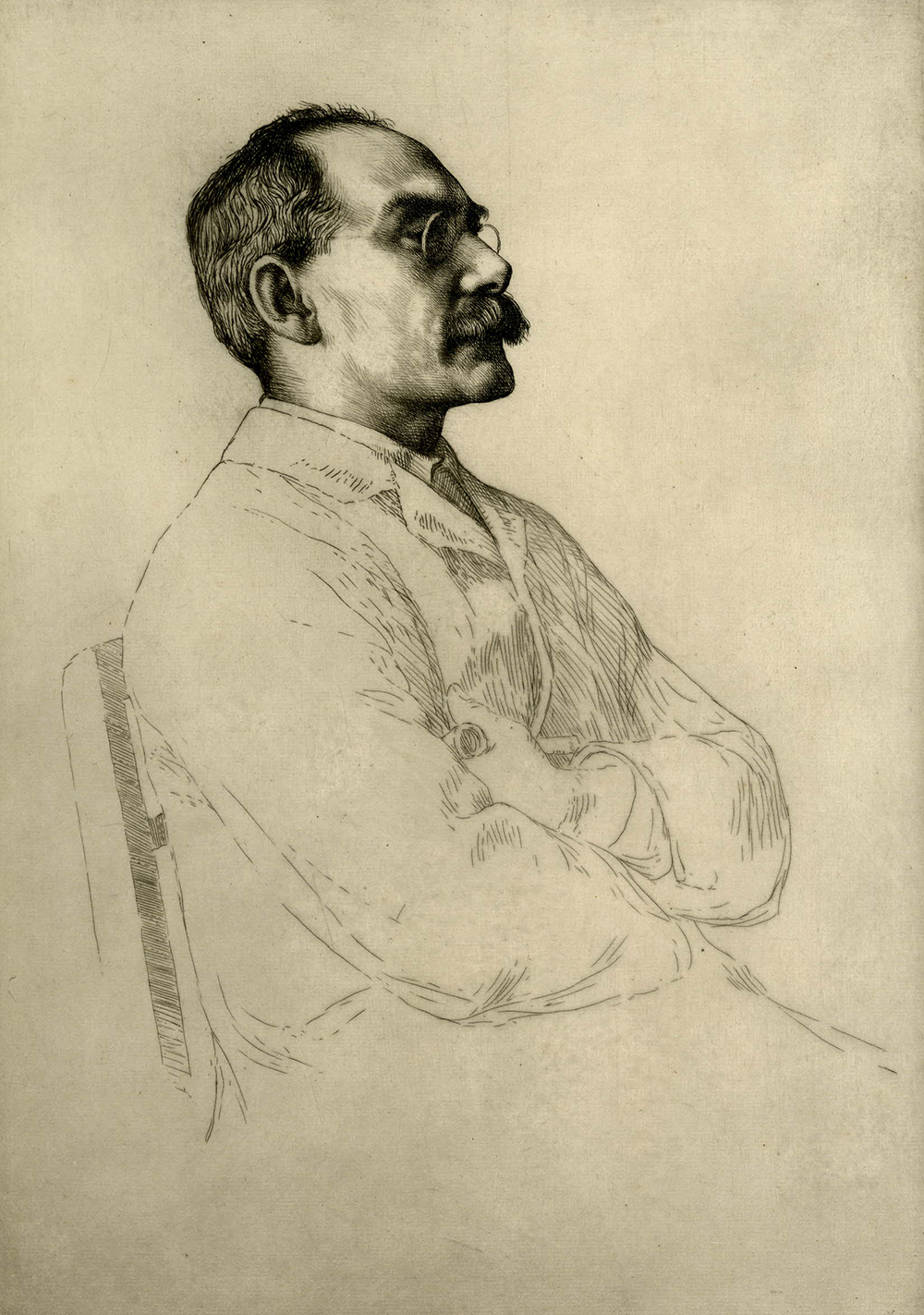

In 1889 Rudyard Kipling received a letter from a young woman in whom he had evinced an interest, asking him to state his religious beliefs. Her Methodist minister father was concerned that her suitor had papist leanings. Kipling probably found the inquiry tasteless, and it no doubt helped cool whatever residual ardor he might have nursed for his naive inquisitor. But his readers are in her debt, for her question triggered a rare burst of candor from the fiercely private writer. As it happened, Kipling was the grandson of Methodist preachers but far from an orthodox churchgoer. His reply reflects this ambivalence. He believed in “God the Father Almighty,” he wrote back with asperity, but also “in justification by work rather than faith, and most assuredly I believe in retribution both here and hereafter for wrongdoing, and I believe in a reward, here and hereafter for obedience to the law.” In a parting flounce, he added: “There. You have got from me what no living soul has ever done before.”

Kipling was a twenty-four-year-old stripling when he wrote that letter, but he sounds like an old martinet. The granite authority of his beliefs, unsoftened by even the hint of a doubt, is quite astonishing and speaks of a mind that set early. While his ardor for unsparing retribution has a strong whiff of brimstone—and many of his most famous stories, such as Mary Postgate, have a vengeful sheen—the most striking element of his credo is his adulation of the law, which he treats like some kind of secular god. Few writers have paid fealty to the Law (always in respectful uppercase) more fiercely than this proud imperialist. He regarded it both as plinth and keystone of the British Empire—and consequently, in his view, human civilization. It is the moving impulse of his writing and never more explicitly engaged with than in two of his celebrated works written in the Victorian high noon of the 1890s when he, too, was at the height of his literary power.

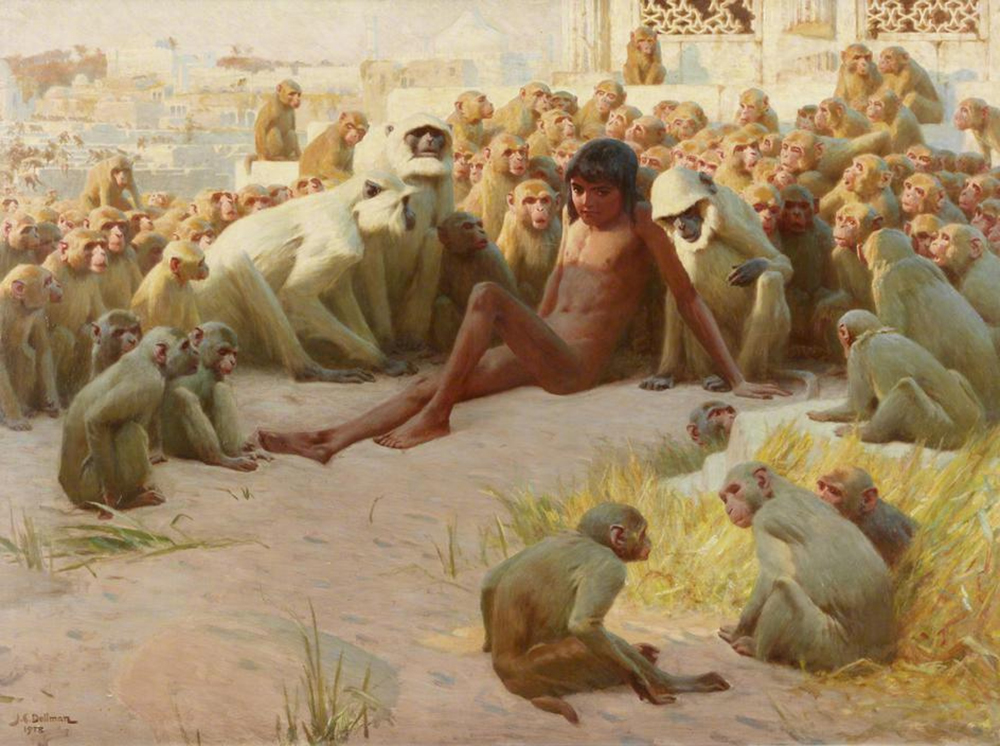

The first is the magnificent and moving Mowgli stories in the two Jungle Books. Like the “giant creeper” that girdles the tree trunk, the Law runs backward and forward through the Mowgli tales, a paradisiacal saga of a boy who grows up in the jungle with a family of animals. Its significance is proclaimed at the outset: “The Law of the Jungle—which is by far the oldest law in the world—has arranged for almost every kind of accident that may befall the Jungle People, till now its code is as perfect as time and custom can make it.” Ancient and all-pervasive, it covers every aspect of an animal’s life from hunting to hygiene. (“Wash daily from nose-tip to tail-tip.”) To disobey it is to court ruin for “the Wolf that shall keep it may prosper, but the Wolf that shall break it must die.” To follow the law is not to be servile but to be honorable, as the law is the guarantor of liberty. The disciplined members of the wolf pack take pride in calling themselves the “Free People.”

The law is a compendium of many smaller laws, but its central and overarching commandment is obedience:

Now these are the Laws of the Jungle, and many and mighty are they;

But the head and the hoof of the Law and the haunch and the hump is—Obey!

To modern ears, the demand for unquestioning obedience has a primitive and chilling ring—today’s mantra is more likely: question first. But in Kipling country, obedience is a mark of honor. Every sentient forest creature, from the cocky man-cub Mowgli, who grows up to be the much-feared Master of the Jungle, to the powerful old python Kaa, follows and honors it. Every jungle denizen except for, of course, one infamous group of abstainers: the Bandar Log, or the Monkey People. This demimonde lives in the treetops without a leader, without customs, without memory, without hygiene, without purpose, and without law. Shallow and restless, their lives are an anarchic carnival of boasting, tree-swinging, whooping, and mimicry:

They would howl and shriek senseless songs, and invite the Jungle People to climb up their trees and fight them, or would start furious battles over nothing among themselves, and leave the dead monkeys where the Jungle People could see them. They were always just going to have a leader, and laws and customs of their own, but they never did, because their memories would not hold over from day to day, and so they compromised things by making up a saying, “What the Bandar Log think now the jungle will think later,” and that comforted them a great deal.

When Mowgli makes the mistake of talking to them he gets a sound scolding from Baloo the Bear, who is in the process of teaching him the Law of the Jungle. Baloo’s admonition sounds like the anti–Song of Ruth: “We do not drink where the monkeys drink; we do not go where the monkeys go; we do not hunt where they hunt; we do not die where they die.” He reminds his truant pupil that “the Monkey People are forbidden, forbidden to the Jungle People. Remember.”

The other work in which the law is a lodestar is “Recessional,” the majestic and somber poem on the perils of arrogance and forgetfulness. Kipling wrote it as a response to the braggadocio surrounding Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee in 1897; it was published in The Times, as grand a pulpit as a poem could hope for. A hymn against hubris, it sounded a high cautionary note against what Kipling saw as a growing complacency and boastfulness besetting the national character. The poem’s sonorous Old Testament cadences once again made him sound more like an old prophet than a young poet, or to use a more proximate analogy, like Baloo the bear scolding his feckless countrymen for their follies—an image not quite as comical as it appears if one recalls that the animals in the Jungle Books, with their burnished locution, sound as if they had escaped from the King James Bible.

The gravamen of “Recessional” ’s critique is the same as Baloo’s lesson to Mowgli: remember the law. But it also contains perhaps the most controversial line Kipling would write. It occurs in the stanza where he warns his countrymen that being drunk with power would turn them into braggarts, reducing them, in essence, to the equivalent of the despised Bandar Log. Or, in the condemnatory words of the poem, to “lesser breeds without the law.”

If, drunk with sight of power, we loose

Wild tongues that have not Thee in awe—

Such boasting as the Gentiles use

Or lesser breeds without the Law—

Lord God of Hosts, be with us yet,

Lest we forget, lest we forget!

These two works are conjoined at their cores by an overlapping question that has spurred biographers and critics into all manner of interpretations and contortions: Who are the Bandar Log? Or, interchangeably, who are the “lesser breeds without the law”?

There is no consensus about who Kipling had in mind when he wrote of “lesser breeds.” But the racial odor of that rebuke trailed Kipling for the rest of his days and continues to perfume his reputation. His more sympathetic biographers explain it as a brash expression of Anglomania directed not at Asians and Africans but at Germans. The German theory is trotted out as a mitigating factor, as if to say, “Look, he wasn’t a raving white supremacist, he had contempt for Europeans as well.” It is true that Kipling presciently predicted that a navally rearmed Germany posed the greatest threat to British interests, and indeed he spent the decade before World War I in such a lather of Hun hate (he insisted on calling them Huns) that he seemed touched, like Tabaqui the jackal, with a bad case of dewanee, or jungle madness. But this German theory isn’t convincing.

Kipling clearly had non-Europeans in mind when he wrote about the far-flung gentiles to whom Anglo-American argonauts would bring the flame of reason and law. This theory aligns with the writer’s conservative racial politics, and is strengthened when viewed in tandem with the zealous rhetoric of the poem Kipling wrote two years after “Recessional,” “The White Man’s Burden: The United States and the Philippine Islands.” A thematic twin, it urged his hawkish friend, then Vice President Theodore Roosevelt, to take up the burden of Empire and colonize the Philippines, full of “new-caught, sullen peoples, / Half devil and half child”—an even coarser iteration of “lesser breeds without the law.” Roosevelt described it as “rather poor poetry, but good sense from the expansionist standpoint.”

The Bandar Log are easier to explain—or are they? At an obvious level, if the glossy and disciplined wolf pack is a metaphor for the British and the progress they bring, then it follows that the Bandar Log must be the chaotic Indians in need of a good dose of colonizing to get them in line. More likely, the caricature is not aimed at Indians at large—not at, say, the peasant toiling in the field or the soldier enlisted in the British army. These humble groups won Kipling’s compassion and regard.

His spleen was reserved for the Indian National Congress, an organization at the vanguard of the freedom movement that was largely led by Western-educated, English-speaking Indian intellectuals (men like M.K. Gandhi) who held debates and put forward petitions for increased political representation for Indians. For Kipling, these were the mimic men, the monkeys—in one essay he describes the Congress as being composed of people “who, though they foment dissension and death, pretend great reverence for the law which is no law.” The Congress was formed in 1885, when Kipling worked as a young journalist in India, and was no doubt at the top of his mind when he was writing these stories a few years later in faraway Vermont, where he lived for three years after he got married.

As it turns out, Kipling got so sick of being asked about the Bandar Log that in a 1919 letter to his friend, the French writer Andre Chevrillon, he offered a tetchy annotation:

Now as to the Bandar Log, this was written in 1894 and faithfully reflected, as it does today, my views on the Great God “Democracy.” It had nothing whatever to do with the French, and as I think I have told you, that amiable theory must be a Hun-made one. But it is a reasonable presentment of “government by popular opinion” in whatever part of the world it may be adopted. In England it was assumed to be a picture of the Radical Party, which did me no especial service. The U.S.A. journals thought it reflected on the Republic which is the inevitable result of any attempt at impersonal portraiture.

In Kipling’s political lexicon, “Democracy” was a catchall for all things rowdy and incompetent. It was thus a serious threat to Empire. The expansive political term included the rabble who craved vulgar, populist rule rather than the lofty diadem of kings and queens; trade unionists who made radical labor demands; empire-haters; Indian intellectuals; and socialists who were nothing but moochers wanting a free ride. England, he ranted, was “rotten with socialism.” In contrast, he lavished praise on Canada for its flinty frontier ethos. “Canada is not yet an ideal Democracy,” he wrote approvingly in Letters to the Family.

For one thing she has had to work hard among rough-edged surroundings which carry inevitable consequences. For another, the law in Canada exists and is administered, not as a surprise, a joke, a favor, a bribe, or a Wrestling Turk exhibition, but as an integral part of the national character—no more to be forgotten or talked about than one’s trousers. If you kill, you hang. If you steal, you go to jail. This has worked toward peace, self-respect, and, I think, the innate dignity of the people.

Politicians—the tribe who thrived on democracy—were one of his chief bugbears. Kipling’s first biographer, C.E. Carrington, writes that after visiting President Grover Cleveland at the White House, Kipling came home disgusted and told his wife the men he had met were “a colossal agglomeration of reeking bounders.” “These men,” writes Carrington, “might remind him of the Bandar Log who ‘sit in circles on the hall of the king’s council chamber, and scratch for fleas and pretend to be men.’ ” But even his dislike of politicians paled when compared to the contempt he had for the English liberal who believed the Empire was an embarrassment—and the sooner done with the better. When the wife of his publisher George Macmillan said she thought India should govern itself and that “we in England” should work “in earnest” to enable this, a furious Kipling wrote that “the ultraliberal idiots always speak of we.” The literary world was full of ultraliberals, spurring Kipling to write scathingly of:

long-haired things

In velvet collar-rolls

Who talk about the Aims of Art

And theories and goals,

And moo and coo with womenfolk

About their blessed souls.

It is a deliciously venomous lampoon that makes the London literati sound suspiciously like the Monkey People in the “Road-Song of the Bandar Log”:

Here we sit in a branchy row,

Thinking of beautiful things we know;

Dreaming of deeds that we mean to do,

All complete, in a minute or two—

Something noble and wise and good,

Done by merely wishing we could.

We’ve forgotten, but—never mind,

Brother, thy tail hangs down behind

The chattering monkeys are the antithesis of Kipling’s exemplars—the soldiers, engineers, administrators, bridge-builders, famine-relief workers, and other keepers of the flame working through cholera, heat, and dysentery to hold the line and uphold the ideals of Pax Britannica. In the same letter where he explains who the Bandar Log are, he describes what his journalist years in India had taught him:

As far as imperialism went, my only conception of it was that which I saw around me—men devoted to burdensome tasks under difficult conditions without much assistance or any immediate hope of reward, working for impersonal ends.

For Kipling, this aristocracy of the vita activa would keep England and the Empire safe—not the cricket playing, fox-hunting gentry whom he scorned as “the flannelled fools at the wicket or the muddied oafs at the goals.

It seems strange that a sharp and intelligent observer like Kipling, with a crocodilian nose for cant, failed to see through the humbug of the mission civilisatrice. He couldn’t admit that its cold hard raison d’être was economic profit or that the bridge-builders dying of cholera and dysentery were mere cogs in this centuries-long mercantile raid. Or maybe he did see through it but—à la the Bandar Log—preferred self-deception and deposited it in some kind of Orwellian memory hole. Equally ironic is that while Kipling hero-worshipped men of action, he himself was a man of letters who never fought a single war or, excluding his six-year journalistic stint in India, held a regular job.

Why was Kipling so enamored of the law? The answer is quite simple: it was a guarantor of home. Home was not England, nor India nor the U.S., nor South Africa (where he spent several winters en famille hanging out with his friend and hero, the billionaire imperialist Cecil Rhodes), but all of them together under the canopy of empire. “England is a stuffy little place, mentally, morally, and physically,” he wrote to Rhodes. It was in the empire, that vast imaginary homeland that held “dominion over palm and pine,” that the Bombay-born, cosmopolitan Kipling felt truly at home.

Tellingly, the titular family in Letters to the Family is not a reference to his blood relatives but the diverse family of nations that made up the empire. Long after it became deeply unfashionable, Kipling remained an empire-championing patriot. Born in 1865, less than a decade after the bloody convulsions of the 1857 Indian Uprising, the author was haunted by the specter of transience, the terror that it could all pass away without stewardship and sacrifice—“all our pomp of yesterday is one with Nineveh and Tyre,” warns “Recessional,” while the bleak image of the roofless ruins in the Jungle Book, “like empty honeycombs filled with blackness,” brims with this existential dread. And though he knew that all empires pass away—lasting, he wrote in one of his most beautiful poems, “Almost as long as flowers / Which daily die”—it was vital to be prepared to fight for and defend it to the death.

And therein lies the entrancing paradox of Rudyard Kipling. A man who shouted himself shrill for empire while acknowledging that in time’s eternal span, “cities and thrones and power” last but as long as flowers. “No one will assert that Rhodes and Kipling and Roosevelt believed in the political equality of all men, regardless of their social status, as it is asserted today; they would have contemptuously rejected any such notion,” writes his biographer Carrington. But he qualifies this by adding, “It is equally unjust to suppose that they believed in the absolute superiority of certain racial types. They lived in a world in which the British and the Americans were immeasurably the most progressive of nations; in which their standards of conduct prevailed wherever civilization spread; in which they were in fact spreading those standards all over the world.”

Kipling will remain an enduring enigma—an amalgam of reactionary politics and surpassing imaginative brilliance. What makes him such an entrancing paradox is that he had another side to him, a side drawn by the romance of the forest and the freedom of the road. His two warring halves are memorably captured in The Two-Sided Man, a deceptively playful poem from his masterpiece Kim, and it’s worth quoting a couple of quatrains here:

Much I owe to the Lands that grew—

More to the life that fed—

But most to Allah Who gave me two

Separate sides to my head.

…

I would go without shirt or shoe,

Friends, tobacco or bread

Sooner than lose for a minute the two

Separate sides of my head!

Because Kipling is Kipling, the dutiful side must win—his heroes must choose the life of duty and action. But they are buffeted by conflicting currents, and this inner tension is explored with profound feeling in the closing scene of the Jungle Books when Mowgli decides to leave the forest and return to the village. It is one of the most beautiful passages in the books—a plangent reminder of how the six-year-old Kipling was uprooted from his warm and beloved home in Bombay and sent to a cold and punitive boarding house in England. “Man goes to Man,” chants the jungle. That is the law (and an echo of Kipling’s belief in racial purity). Mowgli is loath to leave but is driven by an urge so deep and strong—the pull of puberty—that he cannot ignore it. But he doesn’t understand what is happening to him. Heartbroken, he begins to weep. “Hai-mai, my brothers,” he cries. “I know not what I know! I would not go; but I am drawn by both feet. How shall I leave these nights?” The animals, older and wiser, know he is responding to the oldest law of all, the law of nature. The edenic fantasy is finished and it is time for the grown man cub to hunt among his own people. They gather around to soothe and comfort him with—what else?—but the ageless wisdom of the Law.

“Nay, look up, Little Brother,” Baloo repeated. “There is no shame in this hunting. When the honey is eaten we leave the empty hive.”

“Having cast the skin,” said Kaa, “we may not creep into it afresh. It is the Law.”

Read more on laws of the jungle and elsewhere in our Spring 2018 issue, Rule of Law.