Portrait of J.S. Bach seated at the organ, c. 1725. Wikimedia Commons, British Museum.

You can hardly find a more sanctioned and orthodox insider than Johann Sebastian Bach, at least as he is typically presented. He is commemorated as the sober bewigged Lutheran who labored for church authorities and nobility, offering up hundreds of cantatas, fugues, orchestral works, and other compositions for the glory of God. Yet the real-life Bach was very different from this cardboard figure. In fact, he provides a striking case study in how prickly dissidents in the history of classical music get transformed into conformist establishment figures by posterity.

“Suppose instead we start to view him as an unlikely rebel,” suggests conductor John Eliot Gardiner in his revisionist study Bach: Music in the Castle of Heaven. Musicologist Laurence Dreyfus, in a spirited 2011 lecture, even goes so far as to label our stolid church composer “Bach the Subversive.” Yet there is tremendous pushback to those who dare taint the atmosphere of respectability and propriety attached to this towering figure, a cultural icon who remains, even today, the poster boy for “serious music.” Amidst the celebrations linked to the 250th anniversary of the composer’s death in 2000, Bach scholar Robert L. Marshall sounded a cautionary tone when admitting that the availability of new information demands a reinterpretation of the composer’s life and works, but he and his fellow experts were “avoiding this challenge and we knew it.” As Dreyfus has pointed out, much of the current writing on Bach comes across as if it is “modeled on the lives of saints.”

I’ve talked to people who feel they know Bach very well, but they aren’t aware of the time he was imprisoned for a month. They never learned about Bach pulling a knife on a fellow musician during a street fight. They never heard about his drinking exploits—on one two-week trip he billed the church eighteen groschen for beer, enough to purchase eight gallons of it at retail prices—or that his contract with the Duke of Saxony included a provision for tax-free beer from the castle brewery; or that he was accused of consorting with an unknown, unmarried woman in the organ loft; or had a reputation for ignoring assigned duties without explanation or apology. They don’t know about Bach’s sex life: at best a matter of speculation, but what should we conclude from his twenty known children, more than any significant composer in history (a procreative career that has led some to joke with a knowing wink that “Bach’s organ had no stops”), or his second marriage to twenty-year-old singer Anna Magdalena Wilcke, when he was in his late thirties? They don’t know about the constant disciplinary problems Bach caused, or his insolence to students, or the many other ways he found to flout authority. This is the Bach branded as “incorrigible” by the councilors in Leipzig, who grimly documented offense after offense committed by their stubborn and irascible employee.

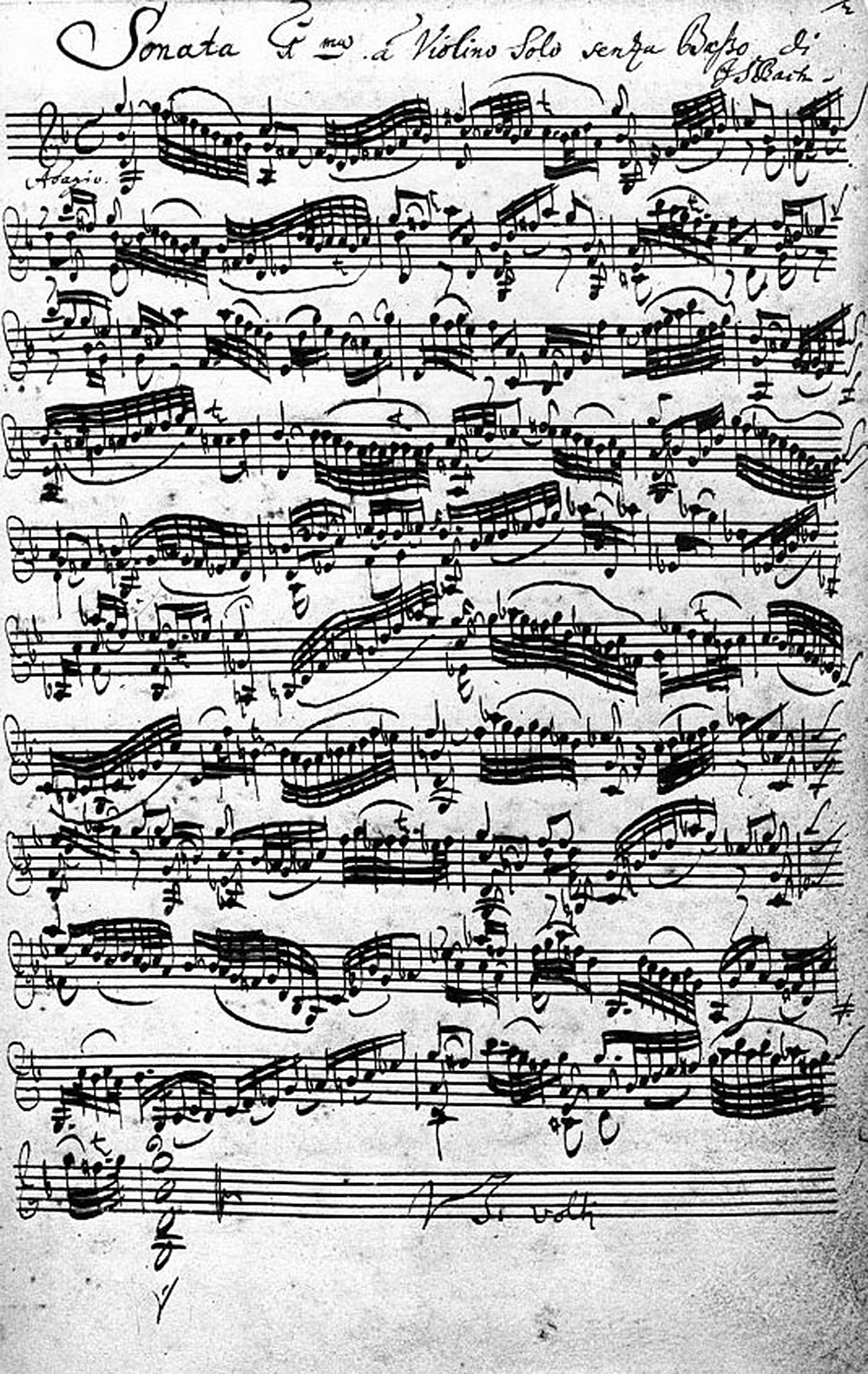

But you hardly need to study these incidents in Bach’s life to gauge his subversive tendencies. Just listen to his music, which in its ostentatious display of technique and inventiveness must have disturbed many in the austere Lutheran community, and even fellow musicians. Not much music criticism of his performances has survived, but the few surviving reactions of his contemporaries leave no doubt about Bach’s disdain for the rules others played by. We hear a complaint about him improvising for too long during church services. We read an angry denunciation from fellow composer Johann Adolphe Scheibe about Bach’s “bombastic” and “confused” music-making. Bach even was forced to provide a memorandum to the city council in 1730 explaining why it was necessary to embrace “the present musical taste, master the new kinds of music.” Here he insists that “the former style of music no longer seems to please our ears,” and demands the freedom to follow the most progressive trends of his day. But perhaps the most revealing commentary comes from Scheibe’s diatribe, where he complains that Bach’s music was “darkened by an excess of art” and marred by an “unending mass of metaphors and figures.” In other words, the very signs of Bach’s greatness for later generations were the same elements that made him suspect during his own times.

These reservations continued after Bach’s death. Some have suggested that Bach’s work was forgotten until Mendelssohn helped focus attention on it in the late 1820s. That’s not entirely true. Bach’s music retained a following in those intervening years, but primarily for pedagogical purposes. There was simply too much to learn from this composer to allow his artistry to disappear. But that didn’t absolve Bach of all his transgressions. Johann Abraham Peter Schulz, a composer who came of age in the generation following Bach’s death, complained that his predecessor’s chorales set a dangerous precedent for those who “would rather display their learnedness…and multiply dissonant progressions—which often render the melody quite unrecognizable—than to respect that simplicity which in this genre is so necessary for the understanding of the common people.” As late as 1800, Abbe Georg Joseph Vogler felt compelled to make Bach’s chorales more acceptable by simplifying complex passages.

When the mythos of Bach’s genius finally emerged, it coincided with a rising sense of German nationalism and a religious revival, movements that envisioned ways they could use this now long-dead composer to advance its own agendas. It’s not even clear that Bach self-identified as a German—rather than as a Saxon or Thuringian. Yet by 1802 his biographer Johann Nikolaus Forkel could proudly proclaim: “This man, the greatest musical poet and the greatest music orator that ever existed, and probably ever will exist, was a German. Let his country be proud of him.” This is the familiar recurring cycle in the history of subversive music. Bach, blues guitarist Robert Johnson, and ragtime composer Scott Joplin are scandals in their own time, but legends at a to-be-determined later date when their legacy can be appropriated by a sanctioned narrative. The role of the music historian is to bring this rehabilitative process into the open, but for some it is all too tempting—perhaps even irresistible—to participate in turning the life story of a troublemaking provocateur into a monument to the new status quo.

Dreyfus specifies six different aspects of Bach’s subversive practice, a veritable manifesto of resistance. According to his schema, Bach subverted conventional notions of musical pleasure—take, for example, the B minor fugue in Book I of The Well-Tempered Clavier, whose theme employs all twelve notes of the chromatic sequence, defying traditional notions of what constituted a beautiful melody. He subverted religious conventions that made liturgical music subservient to logos, the divine word. He subverted prevalent notions of musical propriety, which demanded that expressive style adapt itself to the specific functions and purposes of the occasion. He subverted the dogma that art was a mirror to nature, and must hold on to the most natural forms of expression rather than impose its own self-referential value system on the work of art. He subverted the traditional metrics of musical invention, those time-honored techniques by which melodic ideas were introduced and developed. Finally, Bach subverted the expectations of musical piety, which demanded that the work of art express its devotion in reverent and orderly subservience to the grandeur of God, and not the glory of the composition or its composer. A hagiographer who wants to maintain the reputation of Bach the establishment figure could bicker about one or more of these claims, yet it is impossible to dismiss the gestalt that emerges from a broad-based and open-minded survey of this seminal figure, his life story and body of work. At a very deep level, Bach distrusted officials and power brokers, demonstrating his independence whenever the occasion arose—and sometimes forced the occasion when his muse so demanded. If he eventually became symbolic of the status quo, it was only because the status quo came to adapt to his prerogatives, not the other way around.

Conventional accounts of music history during the century following Bach’s death in 1750 focus on a dazzling expansion of techniques put to use in symphonies, string quartets, concertos, sonatas, and other rapidly evolving platforms for creative expression. It’s worth noting that none of these compositions have anything to do with religious practices—a peculiar state of affairs when one considers how much churches were covering the cost of European music during this same period. Even Bach, the great exponent of Lutheran music, is best remembered nowadays for his secular works—just check out his current-day “best sellers” on the charts if you doubt it. His keyboard music gets more clicks than his cantatas. His Passions and the Mass in B Minor are masterworks of sacred music, but are they heard more often than the Brandenburg Concertos, little known during Bach’s lifetime but played over and over on “drive-time radio,” or his cello suites, now practice-room staples for string players? After Bach’s death, the secularization of musical culture became even more pronounced. Charles Rosen, in the revised edition of his seminal study The Classical Style, notes the hostility from his critics for his scant attention to the church music of the era. But how could Rosen do otherwise? It is, he explains, “unhistorical to pretend that the setting of religious texts did not present very radical stylistic problems in the last quarter of the eighteenth century, and ideological problems as well…That style was stone dead when Haydn wrote most of his masses.”

Excerpted from Music: A Subversive History by Ted Gioia. Copyright © 2019 by Ted Gioia. Available from Basic Books, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.