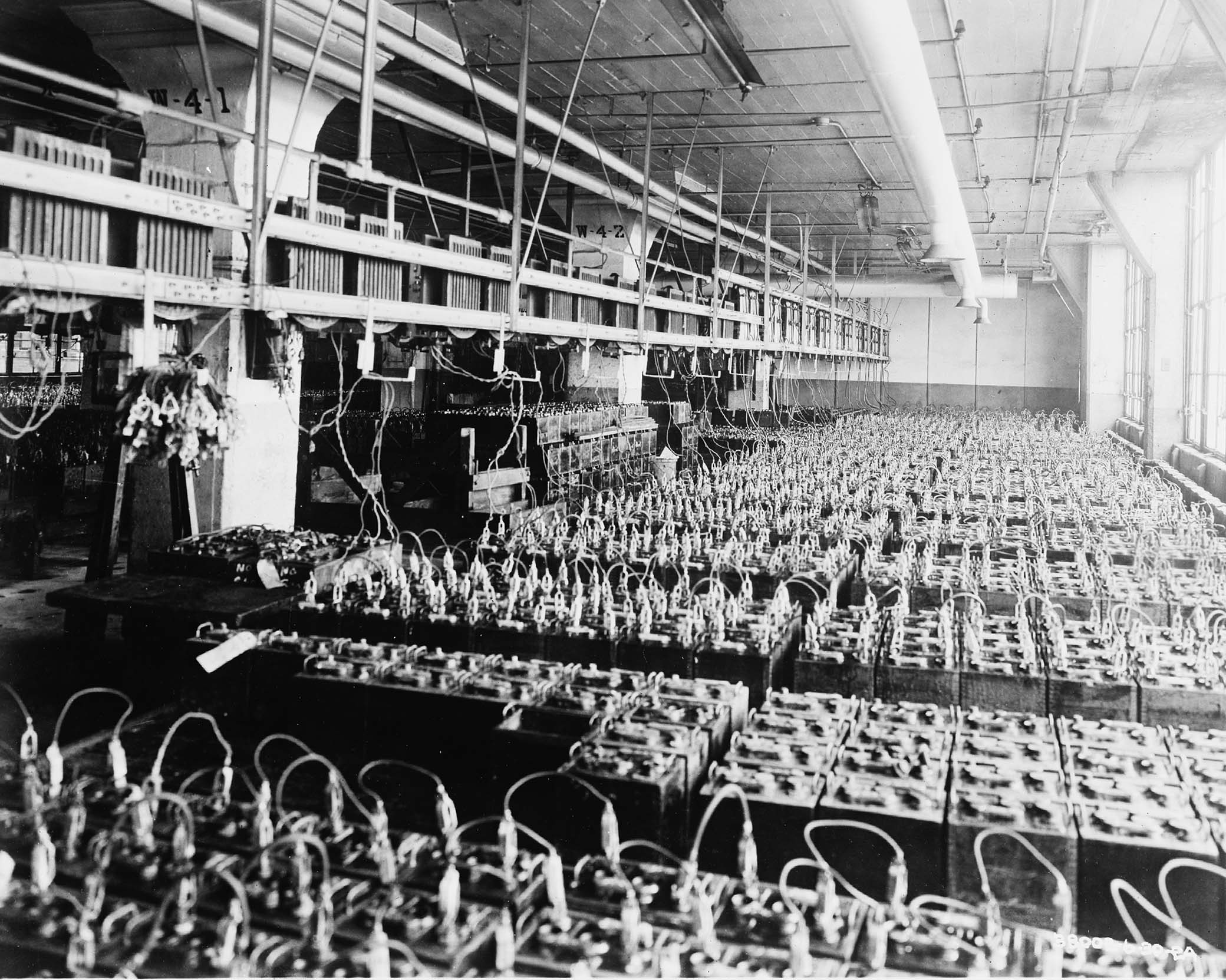

3,500 batteries, 1924. Photograph by Detroit Publishing Co. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

Each year, the Cundill History Prize celebrates the best history writing in English. Lapham’s Quarterly invited the finalists for the 2023 Cundill History Prize to share their favorite works of history—the books that sparked their lifelong interest in the past and to which they return for inspiration and enjoyment.

Today’s reading list comes from James Morton Turner, author of Charged: A History of Batteries and Lessons for a Clean Energy Future, out now from the University of Washington Press.

I came to history late. I was a science major in college, where I tacked between engineering and neuroscience. I was more interested in modeling neurons than digging through primary sources. My turning point was a year abroad in England. I went to Oxford University to study neuroscience. But while I was there, I also needed to fulfill a distribution requirement in history for graduation. It turned out that Eric Foner was also visiting Oxford that year, and he was delivering a series of lectures on nineteenth-century American history. Hearing him reframe nineteenth-century American history turned my late twentieth-century world upside down.

Those lectures sparked my enthusiasm for history and I soon found myself holed up in the Bodleian Library, researching how British newspapers covered the Civil War. I finished college with a neuroscience degree, but I applied to graduate school to study history. Even as dove into the past, I remained fascinated by the sciences. That curiosity has shaped much of my work as a historian and scholar of the environment more broadly.

Nature’s Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West, by William Cronon

Nature’s Metropolis changed how I thought about the ecological roots of capital, the ties between cities and the environment, and how the boundaries we draw between what is nature and non-nature constrain our environmental imagination. My book, Charged, is all about the hidden ties between the technologies important to a clean energy future (such as batteries) and the environment broadly defined.

The urban-rural, human-natural dichotomy blinds us to the deeper unity beneath our own divided perceptions. If we concentrate our attention solely upon the city, seeing in it the ultimate symbol of “man’s” conquest of “nature,” we miss the extent to which the city’s inhabitants continue to rely as much on the nonhuman world as they do on each other.”

Atlantic Crossings: Social Politics in a Progressive Age, by Daniel T. Rodgers

I remember reading page proofs from Atlantic Crossings when I was in graduate school. I was astounded by the reach of this deeply researched trans-national history, the ways it situated policy history in a rich social history, and what it taught me about the power of historical writing. Of the many things I learned from Atlantic Crossings, the one that has been most important is the potential of language to convey the most abstract of concepts in ways that are nuanced, immediate, and compelling. Rodgers wrote about social politics, but that lesson was very helpful, even when writing about batteries.

The paradox of crisis politics is that at the moment when the conventional wisdom unravels, just when new programmatic ideas are most urgently needed, novel ones are hardest to find…One of the most important effects of crises, in consequence, is that they ratchet up the value of policy ideas that are waiting in the wings, already formed though not yet politically enactable.

Toxic Bodies: Hormone Disruptors and the Legacies of DES, by Nancy Langston

Toxic Bodies uses the story of diethylstilbestrol to open a window into the ways synthetic chemicals have shaped environmental history, linking the inner workings of our bodies to the ecosystems we inhabit. The book is an introduction to the complexities of endocrine disruptors, and the ways in which regulators have failed to grabble with their longstanding consequences for human and ecological health. In much the same way, my book Charged seeks to pry open the history of batteries to reveal the tangled relationships that link the production of the technologies we depend upon to the health of peoples and landscapes around the world.

Whatever humans do to the natural world finds its way back inside our bodies, with complex and poorly understood consequences. And in turn, what happens inside our bodies makes its way back into the broader world, often with surprising effects.

About the Cundill History Prize

The Cundill History Prize recognizes and rewards the best history writing in English. A prize of $75,000 is awarded annually to the book that embodies historical scholarship, originality, literary quality, and broad appeal. The two runners-up each receive $10,000. Administered by McGill University in Montreal and awarded by a distinguished jury, the Cundill History Prize honors the abiding passion for history of its founder, F. Peter Cundill, by encouraging informed public debate through the wider dissemination of history writing to new audiences around the world. Any historical period or subject is eligible, and translations into English are warmly welcomed. Books are accepted regardless of the nationality or place of residence of their authors.